When University of Miami librarian Cristina Favretto asked celebrity chef Norman Van Aken to share memories — literally anything in writing — to document his career for the school's new food-related archives, the Miami toque initially came up empty-handed.

Known for his daily changing menus, Van Aken's dishes were often created and abandoned the same way seasonal ingredients and tastes often do — too frequently. There wasn't much he held onto.

But there was one thing he did have: a 1992 receipt he'd saved from years ago documenting the lengthy list of dishes Julia Child had ordered while visiting a popular Miami Beach restaurant, a Mano, where he served as executive chef. The long-shuttered restaurant was known for its plush interior, exquisite service, and a daily-changing menu critics described as "New World" and "Miami-American."

So if you've ever wondered what Julia Child's favorite a Mano dish was (she ordered the snapper), or perhaps what it was like to grab a late-night meal at Wolfie's in Miami Beach in the 1950s, or even questioned the types of recipes South Floridians were following decades ago, there's a place in Coral Gables that holds all the answers.

These relics of the past are just a snippet of the information found across a vast array of rare books, artwork, manuscripts, and photographs compiled by Favretto for the University of Miami's Department of Special Collections.

From 15th-century tomes to 21st-century cookbooks, the archives are home to vast volumes of information — more than 600 collections and approximately 50,000 rare published works — that document the history of Florida, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and beyond.

The best part: you don't have to be a student to access these archives.

In early 2020 — just months before the onset of the pandemic — the university repurposed a storage room into a mixed–use event space and public reading room. Today, it stands as the hub of the Special Collections department, located at the university's Kislak Center, named for one of the university's top rare item donors, Jay Kislak.

The space offers both students and guests the opportunity to access these materials in serene silence, browsing everything from small-edition books from the 1450s to the hundred of boxes of archived materials that catalogue the history of the Pan Am airline. (It's best to make an appointment so staff can pull materials, many of which are housed offsite.)

Today, Favretto continues to acquire new additions and source materials near and far. Since taking the position as Head of Special Collections at UM's library in 2008, she — alongside University archivist Nick Iwanicki — oversees hundreds of items spanning many topics.

While not everything is specific to Miami and its history, many archives provide valuable insight into the Magic City's past. And, at least for Favretto, some of the center's most colorful items are all about food.

Favretto tells New Times that it was important for her to seek materials to help document the diaspora of Miami's edible melting pot.

"I've always been interested in culinary history, and I've carried that with me," says Favretto, who held a variety of librarian duties for institutions including the Boston Public Library, Duke, and UCLA, curating and building collections much like the one at UM.

It's a pursuit she began during her time at Duke University, where she worked to compile one of the country's foremost collections of prescriptive literature, works that shed light on the lost art of domesticity. Through the collection of instructional pamphlets, magazines, and cookbooks dedicated to domestic culture, she learned to appreciate how food — the way we acquire, prepare, and share it — could reveal secrets from the past in a unique way.

That love of food history came full circle when she began working at UCLA, allowing her to explore, document, and preserve historical elements of the city's vast culinary scene.

But when Favretto first began compiling materials in Miami, she wasn't sure what she'd uncover.

It began with a half dozen household guidelines — many published works from the 1930s and '40s that instructed guests on everything from hosting a dinner party to the responsibilities of household staff. Others acted as early "how to" guides, offering tips for the first wave of young businesswomen learning the art of balancing career and home.

More recently, the collection has blossomed to include spiral-bound cookbooks, colorfully illustrated magazines, and old menus that paint a picture of what it was like to eat in Miami before it was the Michelin-rated gastronomic scene it is today.

Visit the Kislak reading room, and you'll discover that our region's food culture depicts a colorful tapestry of subtropical influences that go beyond key lime pie and stone crabs.

Among the early cookbooks Favretto and her team have compiled, dishes share common ingredients Miami chefs still use today, while others have been lost to both time and taste.

Most materials date back to the 1950s and highlight the Seminole tribe and early Caribbean and Bahamian influences. Familiar fruits like papaya, guava, coconut, and mango are found in every manuscript, but also sea grape, rosella, and natal plum. Likewise, seafood such as crab, lobster, snapper, pompano, and grouper are there, but we no longer see the once-popular turtle soup, Everglades-sourced frog legs, gopher gumbo, or squirrel stew.

A book dubbed "Living Off the Land" by Marian Van Atta that once sold for $1.95 shares recipes that instruct people how to live off Florida's fauna and flora. Recipes include jams and tapioca puddings made with all manner of wild fruit, steamed coquinas (small clams), barbecued wild boar, and boiled armadillo served over dumplings or boiled potatoes.

"What's Cooking in the Caribbean," a spiral-bound book published by the Ladies Guild of the Foreign Colony in 1957, shares more familiar dishes — Dominican recipes for yucca fritters or guava and jelly cheese rolls. "The Bahamian Cookbook," a collection of recipes from Nassau women compiled by Leslie Higgs in 1974, points to our longtime love for dishes like fresh-caught baked grouper and conch fritters. And the "Seminole Indian Recipes," printed in 1987, shares early staples like sea grape soup and alligator tail steaks.

When they weren't cooking at home, Miami's early restaurant patrons ordered everything from all-day breakfast items to lavish meals.

A 1955 menu from Caribe Restaurant in Key West acts as a map and guide, highlighting points of interest like the Southernmost Point, Little White House, and Ernest Hemingway's former residence alongside tips for local dishes. They include native Florida fare like rock lobster, red snapper, turtle steaks, and key lime pie.

A 1950 Wolfie's menu shares what a typical breakfast, lunch, or late-night meal would cost at the popular all-day Miami Beach cafe and Jewish delicatessen that opened in the 1940s and closed in 2008.

Located at the intersection of 172nd Street and Collins Avenue in Sunny Isles Beach, when it first opened, a single fried egg was 30 cents, "appetizers" like lox and cream cheese served with fresh rolls cost 65 cents; a "Hollywood" salad of mixed greens, chicken Julienne, salami, tongue, and Swiss cheese was $2 for two people; and a daily special of made-to-order corned beef hash cost 75 cents.

Best known for its overstuffed sandwiches, one of the most expensive items on Wolfie's menu wasn't the 95-cent combination of kosher corned beef and Romanian-style pastrami — the likes of which demand $15 or more today — but roast turkey with ham, Swiss, lettuce, and Russian dressing, which sold for $1.50.

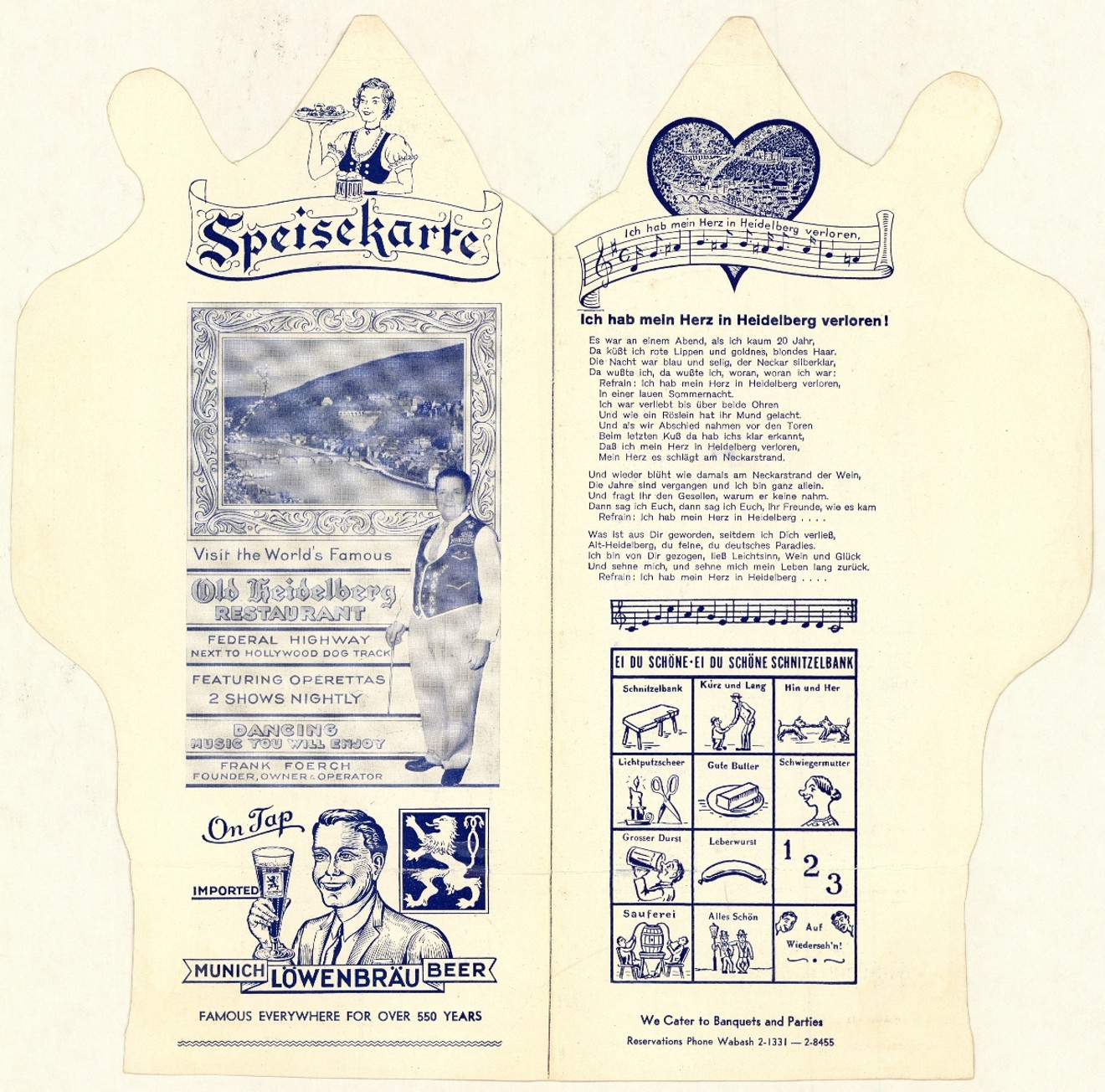

But it's an illustrated menu shaped like a stein that offers a look at one of the area's longest-standing restaurants, Old Heidelberg in Fort Lauderdale. The nearly 80-year-old menu tells the story of founding owner Frank Foerch, who opened the original establishment sometime in the 1930s, a half mile from Gulfstream Park in Hallandale. His dream: to bring something "new, different, and original" to Florida, it states.

At the time, the restaurant offered guests two live entertainment shows a night paired with live music, dancing, and an a la carte menu known for its pig's knuckles, Hungarian beef goulash, Bavarian bratwurst, Wiener schnitzel, and roast prime rib. In the '50s, appetizers like the Florida fruit cup and chopped chicken liver cost 50 cents, entrees no more than $5, and a martini was 95 cents.

Nearly a century later — and two owners since Foerch — diners can still visit Old Heidelberg, which moved to its current Fort Lauderdale location in 1986, according to staff. The walls at the entrance document the past through pictures, from black and white to color, sharing glimpses of the venue's storied history.

And while the menu has changed considerably over time, a few things remain the same: the goulash; a platter of housemade sausages; sauerbraten served with dumplings and red cabbage; and a warm apple strudel.

"Food says so much about a time and place," sums up Favretto. "What we eat tells us a story, too. It's a shared history we can all appreciate."

University of Miami Libraries. 1300 Memorial Dr., Coral Gables; 305-284-3233; library.miami.edu.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]