According to a Florida State University analysis released yesterday, that problem is most acute in Miami-Dade County, where a black student's rate of "exposure" to white classmates dropped from 10 percent to 5 percent from 1994 to 2014, the second-highest rate of racial segregation in Florida. On top of that, Miami-Dade contains the state's highest concentration of so-called apartheid schools, where 99 to 100 percent of the students are nonwhite.

In terms of a student's likelihood of going to school in a racially segregated environment, Miami trails only one district: the intensely segregated Gadsden County Schools north of Tallahassee in the Panhandle, where exposure rates dropped from 8 percent in 1994 to just 2 percent in 2014.

However, Gadsen's student body is far tinier: The district had only 5,709 total students in 2014, compared to Dade County's 352,042. It's hardly fair to compare the two. Miami-Dade's black students have had the second-lowest rates of exposure to whites for the past 20 years, and segregation continues to worsen.

The issue is complex. Modern school segregation is largely a function of housing and income segregation, and Miami remains a deeply segregated city, with low-income black residents largely pushed into areas near Overtown, downtown Miami, Little Haiti, and Liberty City, and low-income Hispanic residents primarily living in the south and west portions of the county.

Miami-Dade also has a small population of non-Hispanic white people — just 15 percent of the county's residents identify as non-Hispanic white Americans, according to 2010 U.S. Census data. The study doesn't differentiate between white and nonwhite Hispanic students, which somewhat complicates the data.

But that's no excuse for Miami's comparatively small white population to place (literal and figurative) walls between it and residents of color. According to the data, Miami-Dade public schools have become

The report makes clear that Florida counties have not done nearly enough to combat both racial and income segregation since the '90s. The two have largely gone hand-in-hand: Discriminatory housing policies "red-lined" Miami's black residents into the neighborhoods where they largely now live. Many of those areas remain low-income communities, while white residents tend to sequester themselves away from low-income earners.

"The proportion of low-income students in Florida public schools reaches nearly 60 percent," the report says. "The typical Hispanic student and typical black

The report blames a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions that greatly limited public school systems' ability to desegregate their populations: The court ruled that once a school had taken all practical steps to become a "unitary" (meaning simply fully desegregated) school, it could legally end its desegregation programs. In practical terms, this meant a school could theoretically bus students to different schools to balance its diversity rolls, and once the government deemed those numbers equal, those programs could end and things could just return to how they had been. The data suggests that across Florida, as long as schools are drawing from segregated communities, desegregation policies are still needed.

"In some important cases, the federal judges actually took the very unusual step of taking the initiative to begin the resegregation process even when the district did not want

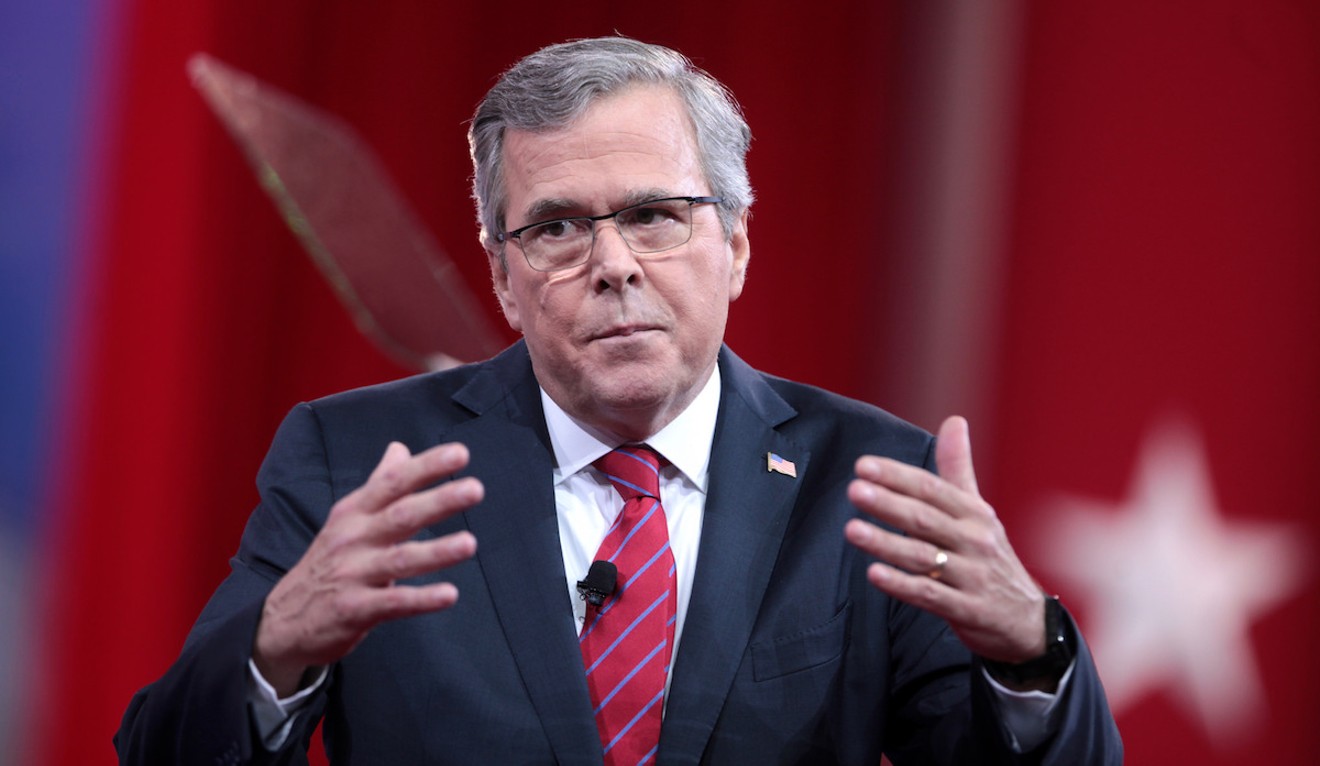

The study also undercuts a different dataset that made the rounds online yesterday. The nonprofit, nonpartisan Urban Institute released data that suggests the state's school-voucher program, the Florida Tax Credit (FTC) Scholarship Program, which uses corporate donations to pay for low-income students to attend private schools, helped those low-income students enroll in college. Proponents of the so-called school-choice movement (e.g., conservatives such as the Koch brothers, Jeb Bush, and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos) cheered the study as a confirmation that Florida's education-privatization plan is a success.

But state segregation data shows the debate is far from complete. For one, the study simply compared current private schools to underfunded public ones — but didn't examine whether sending cash to underfunded public facilities could work better. (In a follow-up blog, the study's own authors also said they were unsure whether the comparatively small FTC program could work at a larger scale.)

Second, Florida's FTC program has existed since 2001, but in that time, segregation has only worsened across the state. School-choice programs have long been accused of either doing too little to help fix racial-segregation issues or even making those issues worse. (In fact, the concept of school vouchers came about in the 1950s as a way for white students to avoid attending racially integrated schools while still receiving taxpayer funding.)

FSU's new report deals explicitly with the school-choice programs instituted in Florida under Bush and the state's subsequent conservative governors — and castigates those administrations for basically forgetting about racial equality for decades. The report says that after Bush took office in 1999, he greatly expanded the state's voucher and charter programs while also becoming "the first governor in the U.S. to end affirmative action in higher education under his own authority."

After his brother became the president and instituted the No Child Left Behind Act, the state's public school system became hyperfocused on test scores and simply ignored that its schools were becoming less racially diverse, FSU's researchers say.

"With intense pressure on schools to increasing[ly] perform on high stakes state testing program[s], segregation became a diversion and, even worse, an excuse," the report states. "When the schools did not perform, and a very disproportionate share of schools with double segregation by race and poverty were branded with D’s or F’s, the state, under the leadership of Gov. Jeb Bush, blamed them, sanctioned them, and encouraged the growth of charter and voucher schools. Without attention on segregation and its remedies, the goal of racial diversity was ignored."