Florida's rainy season began so slowly this year that farmers worried they would spend the summer under drought conditions. But then, in late June, a month's worth of rain suddenly poured on Florida in just one week. The deluge swelled the artificially managed water levels in the Everglades, flooding the habitats of deer, endangered birds, and other critical animals and plants.

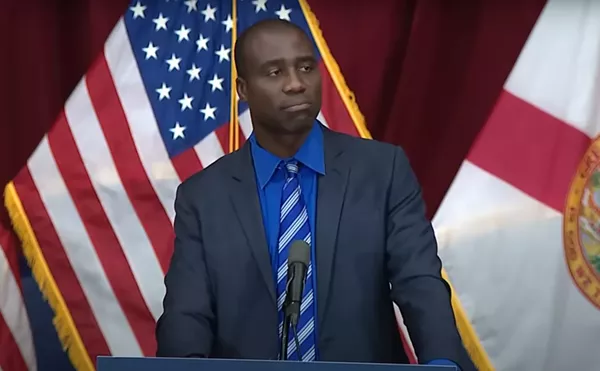

The flooding grew so severe that the South Florida Water Management District was forced to pump more than nine billion gallons of water, enough to fill 14,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools, into Lake Okeechobee. Commissioner Ron Bergeron of the Florida

But now one environmental group says the devastating floods are not simply an act of God: The real culprit, they say, is Big Sugar, which reroutes massive overflows to prevent its cane fields from going underwater.

"The statement from Bergeron was that there 'may not be an Everglades left to save,'" says Peter Girard, an activist from Bullsugar, a nonprofit that combats the sugar industry's oversize influence in Florida politics. "If it’s that dire, maybe endangering the sugarcane yield is the best option."

Bullsugar released a short analysis last week claiming to show that a significant portion of the water "flooding" the Glades had actually been pumped out of the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA), a swath of farmland in Central Florida on which cane-growing fields are used by the state's largest sugar companies: Florida Crystals (owner of Domino Sugar) and U.S. Sugar.

Whenever the EAA receives significant rainfall, farms pump out water full of agricultural byproducts such as phosphorous, which pollute the Glades. Bullsugar estimated that because sugar fields take up 424,000 acres in the EAA, 15 inches of rain on top of those fields would create 173 billion gallons of rainfall that needed to be pumped out of the area. That much water, Girard wrote, is "roughly the volume of polluted water that poisoned the Treasure Coast during 2016’s Toxic Summer discharges," when bright-green algae blooms could be seen from space.

Spokespeople for Florida Crystals and U.S. Sugar didn't immediately respond to messages New Times sent Friday to respond to Bullsugar's claims. But considering the current flood conditions,

Bullsugar activists cede that letting the EAA flood for short periods of time could hurt sugar yields. But they say such a measure might be necessary to save the Glades, especially because, in addition to simply flooding the area, pumped-out water typically contains agricultural pollutants. In 2014, the environmental group

"Where did [the water] go this time?" Bullsugar asked in a letter last week. "Some went into the lake, of course... That didn’t stop a massive amount of sugar runoff from going into the Everglades. How much? Enough to raise water levels south of the EAA to the point where animals drown or starve. Enough to pressure federal agencies into allowing water onto the nesting grounds of the endangered Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow."

Girard notes that the Glades' ecosystem regularly floods during periods of heavy rainfall, but few politicians or reporters accurately estimate how much comes from water pumped from sugar fields.

Girard and Bullsugar aren't the only activists to tie the flooding to Glades sugar farms this year. Eric Draper, executive director of Audubon Florida, told the Treasure Coast Palm it's "accurate to say the district is taking all these measures to reduce environmental harm, particularly [pumping floodwater into Lake Okeechobee] to keep wildlife from drowning. But they're also doing it to keep the Everglades Agricultural Area from flooding."

In fact, conservation activists concerned about the Glades and Lake Okeechobee have fought flood-control experts in the state for decades. But the activists at Bullsugar say the state and public don't put enough pressure on sugar companies in situations such as this one.

"We’ve definitely got a bias here," Girard says. "The state certainly communicated that this is disastrous to the entire Everglades system. If the magnitude is that high, as much detailed information as possible should be made to the public." (Bullsugar, it should be noted, is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit and, therefore, does not need to reveal its sources of funding to the public.)

On a tour with reporters two weeks ago, the Fish and Wildlife Commission's Bergeron warned that flood conditions could be destroying an area that millions rely on for sustenance.

“This whole environment has a lot to do with our quality of life,” he said, according to the Miami Herald. “Nine million people depend on it for their drinking water, so it ain’t no play game.”

The Herald noted that South Florida water managers pumped billions of gallons of treated water back into Lake Okeechobee, while the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers warned that other levees that protected densely populated areas of South Florida were close to overflowing. But none of the state officials seemed to mention that, in the meantime, the EAA had been pumped dry.

In its letter last week, Bullsugar noted that sugar yields remain remarkably steady statewide despite what the group claims are huge fluctuations in Florida's weather patterns.

"Their yields have grown for almost 40 years, while, God knows, Florida has seen extreme weather," Girard says. "We know water is certainly being pumped out of the EAA and into the Glades. But the state has made no effort to communicate to the public that any other option exists."