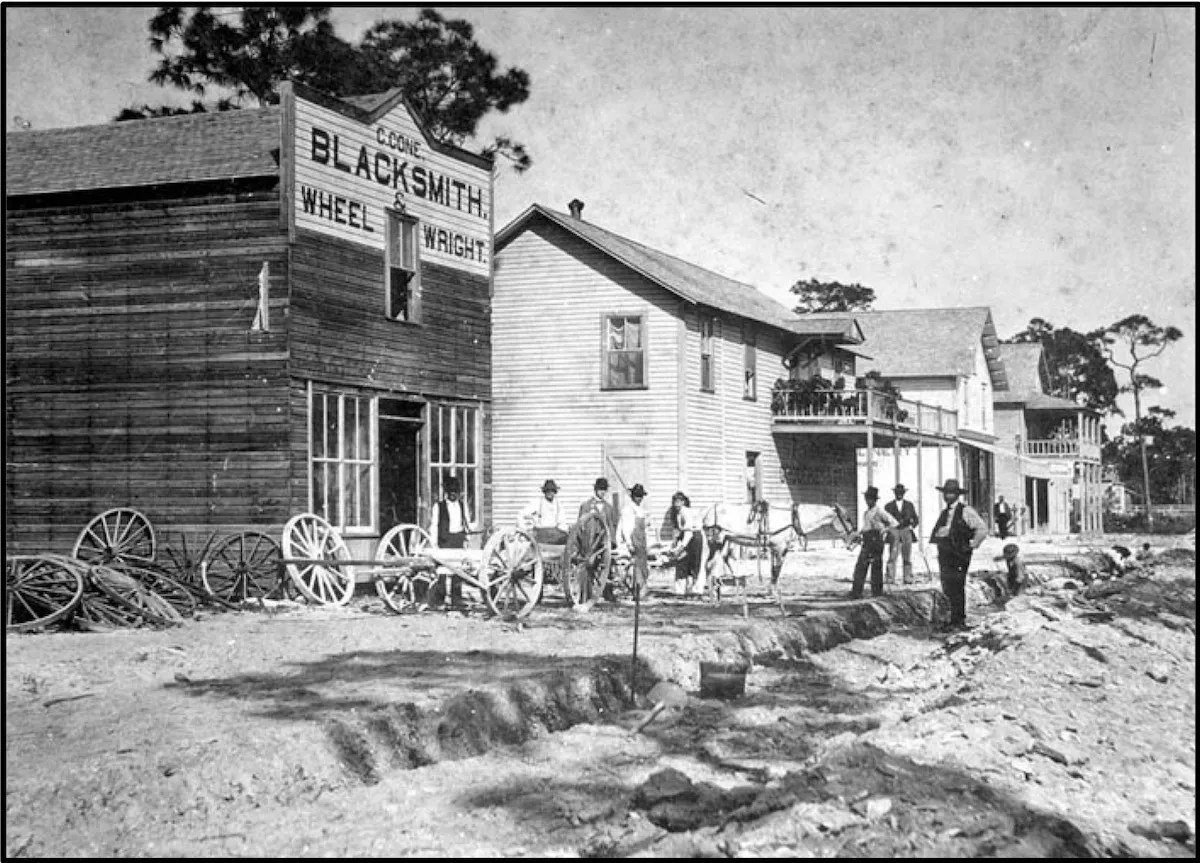

Photo courtesy of the State of Florida Archives

Audio By Carbonatix

In 1899, only three years after its founding, the newborn city of Miami was pushed into quarantine. An epidemic meandered up South Florida’s coast from Cuba and nestled off Biscayne Bay. To stem the outbreak of the mysterious disease termed yellow fever, the State of Florida ordered that no one was allowed to leave or enter the city. Businesses shuttered, temporary hospitals were erected, and the infected were quarantined on steamers anchored offshore.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, such a situation would be difficult for a modern-day Miamian to envision. Although the novel coronavirus and yellow fever are different viruses, they bear many instructive parallels. And though no one who lived through Miami’s yellow fever epidemic of 1899 is alive today, the city itself remembers.

Miami was home to a mere 1,700 residents in 1899. Despite its explosive population growth following its founding in 1896, the city remained a small frontier town nestled in a remote, tropical wilderness on the bay. Flagler Street was very much the central hub of business and commerce. Dusty and unpaved, it made its way west from Biscayne Bay and was lined with two dozen brick buildings, none of which climbed higher than four stories. Though isolated and unassuming, Miami was burgeoning. It was on the fast track to fulfilling its destiny and becoming the shining city on glistening waters – the Magic City.

That is, until August 31, 1899, when growth, commerce, and community were put on pause as people hid in their homes from a menacing, life-threatening sickness that swept through the infant city and infected more than 13 percent of the population.

In the absence of scientific evidence, misinformation and superstition ran amok.

It was on that day that the passenger steamship The City of Key West arrived in Miami. Vessels like the Key West could be described as proto-cruise ships, traveling around the world and equipped with hundreds of cabins for passengers. This particular ship, however, carried Miami resident Samuel R. Anderson. Shortly after disembarking, Anderson took ill and was examined by Dr. James Jackson, the cigar-puffing physician for whom Jackson Memorial Hospital is named. Jackson and the three other doctors who lived in Miami had little firsthand experience with yellow fever and were compelled to seek consultation from outside the city.

In the meantime, Anderson was confined to his Miami residence, where two “immunes” stood sentry. Once the yellow fever diagnosis was confirmed, the patient and his family were quarantined on a schooner anchored in the waters just north of Key Biscayne. But was it too late? Had the outbreak taken root in Miami? A silent uncertainty permeated the city.

The church bells that chimed over I.R. Hangrove’s funeral broke the silence. Hangrove, a dance instructor, was struck down by yellow fever 26 days after the first diagnosed case. The city was on the verge of panic. Very little was known about the disease that in serious cases caused the skin to turn yellow; scientists had yet to determine that it was transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes.

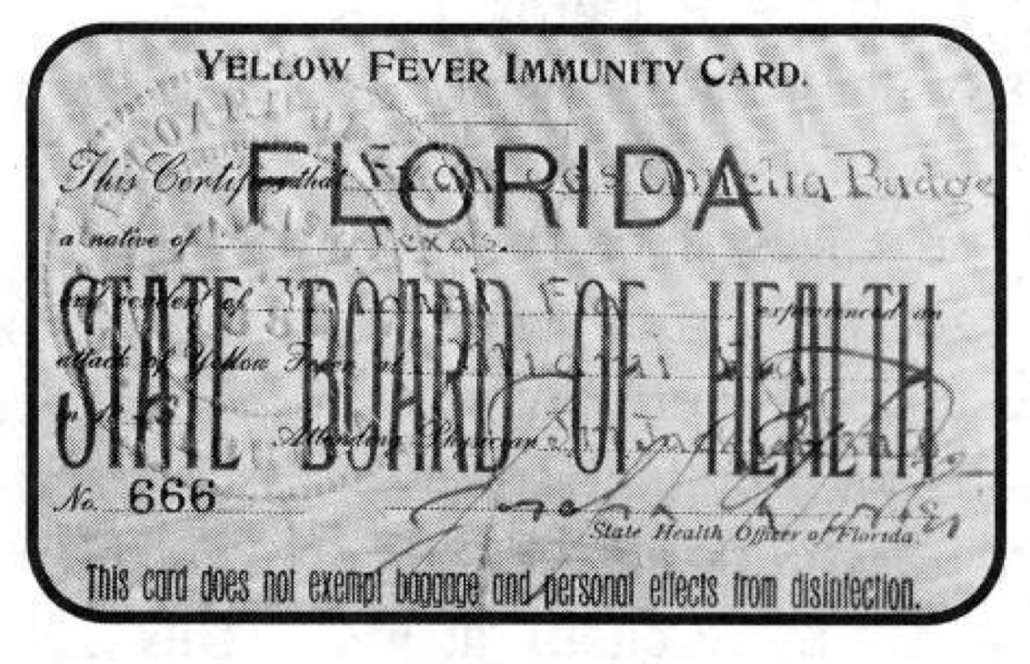

Yellow fever immunity card issued in Florida.

Photo courtesy of Casey Pickette

In the absence of scientific evidence, misinformation and superstition ran amok. The sheriff’s department conducted daily canvasses beginning the day of the dance instructor’s death.

A week passed, then another, with no new cases to report. Still, out of an abundance of caution, restrictions were imposed on travel and nonessential businesses. After 16 days without a single diagnosis, the restrictions were lifted and life began to return to normal. But ten days later, a second death heralded another – more deadly – wave of yellow fever in the city.

With only four resident physicians, Miami was wholly unprepared and lacked substantial medical facilities. Makeshift hospitals and quarantine camps were hastily thrown together to cope with the situation. A hotel on Flagler Street that was temporarily repurposed to house yellow fever patients caught fire and burned to the ground along with five nearby buildings. Subsequently, a massive quarantine vessel was stationed where the Rickenbacker Causeway is today, and another detention camp was set up 12 miles north of the Miami River. A hospital was built with plans to be burned down once the disease subsided, and homes of the infected were marked with yellow flags.

By December, the number of new cases finally began to wane. On January 15, 1900, four months after the outbreak began, Miami’s quarantine was lifted.

In all, more than 220 people had been infected – 13 percent of the city’s population. Twenty-two people died. Only a few months later, a Cuban scientist would discover the mosquito’s role in transmitting yellow fever, resulting in a massive drop in cases worldwide.

With a new experience of adversity under its belt, Miami would soon experience a construction and population boom. Perhaps the unprecedented four-month shutdown forced Miami to take a step back from its day-to-day activities, stay home, and dream about how a new, stronger city would wake from its end-of-century nightmare.