Listen to the full "Loathe Thy Neighbor" story below:

Mark Cantor was pulling his green Mini Cooper into his driveway one evening when a pair of headlights jumped the curb behind him and came barreling across the front lawn, straight toward him.

The 54-year-old graphic designer was barefoot. As usual, he had slipped off his sandals for the slow commute from his Design District office to his house in the Roads — a quiet, leafy neighborhood of single-family homes southwest of downtown Miami.

A meticulous type, Cantor personally maintained his 1930s Mediterranean-style house and its lush array of palms and bougainvillea. He kept the place immaculate and called it his "dream home."

But the headlights careening across his pampered Bermuda grass that night in 2008 were about to turn that dream into an Orwellian nightmare that would force him out of his home, land him in criminal court facing up to 30 years in state prison, and embroil him in a legal battle that has continued for more than 14 years and is still brewing today.

Blue and red strobe lights appeared. Then there were sirens. Two cops aimed guns at Cantor's open car windows: "Out of the car! Hands up! Hands up!"

Looking over his shoulder, Cantor saw squad cars piling up one by one and scores of cops swarming his yard. Startled, he reached down and pulled on his sandals. The cops at his windows panicked: "Get your fucking hands up!"

Slowly, Cantor got out and put his hands on the roof of his car.

Moments later, he was sitting handcuffed in the back seat of a police cruiser as his neighbors gawked. While he tried to figure out why he was being arrested, he watched two cops picking apart his car. They were searching for something.

It's like they just brought down Bin Laden, he thought.

Then he saw the front door open at the house across the street. His neighbor, a 44-year-old recently retired City of Miami Police commander and former SWAT team leader, William "Willy" Alvarez, strode out in trousers and a polo. He patted the arresting officers on their backs.

That's when things began to make sense.

Cantor had been doing what he always did on a Thursday, juggling a hundred responsibilities.

He stood six feet tall, with graying brown hair and a slightly jokey air. He had recently sold his graphic design and advertising company, Pinkhaus Design, after 18 years in business. Now he co-owned Frank Design on the top floor of the historic Moore Building in the Design District, where the constant thump of eclectic music emanating from his office annoyed other tenants.

Those tunes were the soundtrack to success. It was the early 2000s, and Miami's real-estate market was surging. Frank Design had hundreds of commissions to design logos, brochures, signs, billboards, and anything else that a business, or major development project, might need to establish an identity.

It took a lot of people — artists, copywriters, printers, sales reps, and others — to bring an advertising campaign to life. There were business lunches and events to attend with clients. Networking, too, was important, especially at theaters and art galleries.

It was hectic, but Cantor wouldn't have had it any other way. He liked people. More than anything, he liked to talk. If you were in a hurry, you didn't want to run into Mark. If you did, he'd spin a yarn and make you laugh. At social events, the question was always "Where's Mark?"

His office was a microcosm of Miami: mostly Hispanics and a few Anglos (a local misnomer for non-Hispanic whites). Blacks, Asians, Catholics, Muslims, and Jews all came and went. The graphic design community is nothing if not diverse, and Cantor, who did the hiring, couldn't have cared less about race, religion, or ethnicity. If you were good at your job, that was enough.

"He was just an affable, mild-mannered, kind person who lived his life quietly."

tweet this

The son of a doctor, he grew up in North Miami with four sisters and two brothers. He spent only eight years away from his hometown — at a boarding school in Massachusetts and later at Tulane University in New Orleans. Homesickness brought him back, though, and he completed his fine arts degree at the University of Miami.

In 1993, he married Sophie, a young French flight attendant, and soon became a father. In the Roads, the couple found their dream home, a whitewashed 3/2 with vaulted ceilings and clay tiles on the roof. Miami historian Paul George regularly began stopping out front on his popular walking tour of the historic neighborhood to point out the home's architectural features to sightseers.

Cantor's marriage didn't last, but his friendship with his ex remained. He stayed in the house. Sophie moved to nearby Coconut Grove in 2001. Their son went back and forth. When Mark had cookouts in the backyard, Sophie came over. So did some employees and neighbors.

Cantor, some locals might observe, was one of those native-born holdouts who didn't feel the need to relocate as the city's demographics rapidly shifted in the '80s, putting him in the "Anglo" minority that now accounts for 11.2 percent of the city of Miami's population — the smallest non-Hispanic white population of any major American city.

"He was just an affable, mild-mannered, kind person who lived his life quietly, spent time with his son, and I never saw him be any way but just a kind person who instilled trust in me," a neighbor would later tell a jury.

"Marc is a stellar guy, just a stellar guy," a former colleague told the same jury.

When the police descended on his home that evening in 2008, Cantor was known for creativity, sociability, and open-mindedness.

He was not known for stalking, guns, and Nazi salutes.

Willy Alvarez was an expert on two things: criminals and real estate.

In 1984, Miami was struggling with mass immigration, race riots, drug wars, and soaring crime rates. Dade County was the nation's murder capital. Into this mayhem came Alvarez, a handsome, young Cuban-American.

Born in New Jersey, he had moved to Miami as a kid and arrived at the Miami Police Department during that tumultuous summer of 1984. He was 20, barely old enough to qualify for a police job.

He started at the bottom, writing accident reports and performing other nonenforcement duties as a public service aide. Then he went to the police academy, graduated, and became a patrol officer.

Within two years, he had joined the SWAT team. Not everyone who applied made the team. It was elite. Members had to be in top mental and physical condition. They had to respond to crisis calls in the middle of the night. They had to be young. They needed enthusiasm.

Alvarez spent time in the narcotics and missing-persons units in addition to his SWAT duties. Later, in the gang unit, he arrested notoriously violent members of the Latin Kings and 34th Street Players. He also volunteered as an inner-city football coach during the '90s to help steer young people away from those gangs. The kids called him "Coach Alvie."

The '90s brought him a slew of professional laurels. He became a sergeant, a certified firearms instructor, and a supervisor at the police academy and was elevated to SWAT team leader; in that job, he coordinated missions and dignitary protection and figured out how to extract subjects who had barricaded themselves in homes or offices.

He married a Puerto Rican beauty named Betsy in the early '90s. In the Roads, the couple added 2,000 square feet to a little one-story house and turned it into a large two-story home. They moved in around 2001 with their two small children.

Meanwhile, the Alvarezes were brokering and acquiring investment properties. Together, they ran Sterling One Realty, a successful real-estate firm not far from their home that's still active and thriving today.

Alvarez eventually advanced to lieutenant and then commander, nearly the top of the police ranks. He was, he later told a jury, "a very active police officer" and made thousands of arrests during his career.

Former neighbors remember him as an alpha male who religiously worked out with fellow officers at a local gym, competed in triathlons, drove a Hummer with blackout tinted windows, and monitored his block with the true ethos of a cop. If anyone looked like they didn't belong, Alvarez would have a conversation with them. If something looked suspicious, patrol cars would appear.

One day, Alvarez discovered a thief rifling through his car. He pinned the man down until fellow cops arrived and hauled him to jail. The man confessed to 40 other burglaries. He had finally picked the wrong victim.

Alvarez loved being a cop. He could count his friends on his fingers, and they were all cops too. He knew his way around guns, the law, and military-style tactics. He knew how to get things done.

If you were looking for trouble or someone to fuck with, Willy Alvarez was a bad choice.

In the beginning, Cantor and Alvarez waved hello. Sometimes one of them asked, "How are you?"

They ran into each other at a TGI Fridays restaurant in the early 2000s and chatted briefly over drinks. Friendship was never really a possibility. They were of different worlds. But neighborliness was enough.

Their kids attended each other's birthday parties, went to the same parks, and played in each other's front yards.

One day in October 2005, the kids were doing exactly that, tossing a tennis ball on Cantor's side of the street. Cantor was in his backyard cleaning up. Hurricane Wilma had ripped through South Florida two days earlier. His property escaped serious damage, but all over town, trees leaned on homes, electrical wires dangled, and roof tiles littered the ground. Most of the city had no power and temperatures soared.

Then the kids got their ball stuck in a tree. Cantor's 11-year-old son threw a branch to dislodge it, but the branch fell and hit him in the face. Alvarez's son, also 11, laughed and told him he "deserved it." Other kids laughed too. Cantor's boy went to show his dad the large bump on his forehead and began to cry — not because of the injury, but because of the way his playmate had ridiculed him.

Friendship was never really a possibility. They were of different worlds.

tweet this

Cantor marched around to the side of the house and confronted the Alvarez boy for what he interpreted as bullying. "Why did you say that?" he asked.

The Alvarez boy denied saying anything and then began dialing a number on a cell phone he was holding.

Cantor plucked the phone from the boy's hand, leaned forward, and dropped it six inches onto a nearby step. "I want an answer," Cantor said.

The boy wouldn't speak to him, so Cantor turned to leave. As he walked away, he told the boy, "You're a little shit." Immediately regretting his outburst, he tried to turn it into a childish joke. "And I'm not taking that back!" he added.

Sometimes, Cantor admitted, he could be too quick to react.

Alvarez was at work. As a lieutenant, he supervised 25 other officers in the downtown district. That day, he was working an Alpha Bravo shift — an emergency schedule during which half the department worked 12 hours and the other half worked the other 12.

After Hurricane Wilma buzz-sawed through Miami, downtown was a mess. Traffic lights were out. Elevators didn't work. Skyscrapers with blown-out windows made the area look like a war zone. Broken glass was everywhere. Amid the fray, Alvarez's cell phone rang. It was his wife.

Mark Cantor, she said, had just hit their son.

Willy Alvarez sped down a desolate I-95 toward the Roads. Two lieutenants followed in a separate police car.

At home, Alvarez found his son crying in the driveway. Cantor, the boy said, had screamed at him and smacked a phone out of his hand. There was a red mark on his right hand.

Alvarez cried with his son. He wasn't the crying type, but somebody had just hit his kid. He had never even hit his own kid.

He looked across the street. Cantor's car was in the driveway.

"Go inside," he told his son.

The bump on Cantor's son's forehead was green now, and one of his eyes was bloodshot. Cantor decided to take him to North Shore Medical Center, where his father had worked before his death a year earlier. Local hospitals, he knew, would be busy after a hurricane. At North Shore's ER, they might get in faster.

He heard a pounding on the front door. This, according to Cantor, is what happened when he opened it:

"Alvarez comes two steps into my house and stands inches from my face and lets loose. Two other cops are standing on the step facing the street. He's screaming at the top of his voice, spitting on me... Going on and on. Calls me a pussy like a hundred times and every other name trying to get me to fight. My son is standing there terrified, holding ice on his head. Alvarez is shaking he's so mad. I thought he was going to kill me, and I'm trying not to move because he'll say I came at him. I tell him, 'I didn't touch your kid.' He goes crazy again. Finally, he turns to leave; then he comes back and starts up again. It went on for like 15 minutes. It was insane."

Alvarez finally left. Cantor closed the door and thought, What the fuck was that?

At the hospital, Cantor's son was treated and released for his injury, which turned out not to be serious. Cantor dropped him off at his ex's apartment in the Grove and then went to spend the night at a co-worker's house. He thought it best to let Alvarez cool off.

The next day, Cantor told his story at work. Co-workers urged him to file a complaint. He hadn't touched the neighbor's kid, after all.

"I thought he was going to kill me, and I'm trying not to move because he'll say I came at him."

tweet this

He mulled it over, wondering if it would just cause more problems. He knew he'd made a bad move confronting Alvarez's son. But he felt wronged by the accusation of physical abuse and by Alvarez's verbal assault.

Six days later, he filed a complaint with Miami PD's internal affairs unit based on his belief that Alvarez abused his authority by threatening him while in uniform.

Alvarez was called in to make a statement. He told investigators he simply warned Cantor to stay away from his son. He said he had called Cantor a coward but did not scream, use profanities, or make any threats. The whole exchange lasted about a minute, Alvarez said. He had wanted to arrest Cantor for battery, but his wife asked him not to. She didn't want any trouble.

The two officers who accompanied Alvarez to Cantor's house corroborated Alvarez's story. Cantor, they said, was lying. Internal affairs closed the investigation nine weeks later, clearing Alvarez of any misconduct.

Cantor, meanwhile, had taken the additional step of going to the Civilian Investigative Panel (CIP) — a group of 11 citizens who independently review police complaints and issue findings and recommendations to the police department. The CIP was created in 2002 to counter the fact that internal affairs clears officers of wrongdoing in the vast majority of its cases.

Denise Minakowski, the CIP's chief investigator, looked into Alvarez's background. His personnel record showed 35 citizen complaints regarding 40 allegations of misconduct. Most were for alleged abusive treatment and discourtesy. Only one had been substantiated by internal affairs.

Minakowski put Alvarez on a "watch list." But with no independent witnesses and no one to corroborate Cantor's story except his son, the CIP concluded its investigation ten months later as "not sustained for misconduct."

Minakowski quit a year later, claiming CIP staff didn't have the basic tools or support to investigate complaints. Her successor, who served for three years, quit for the same reason.

A few months after the CIP investigation ended, in late 2007, Cantor stood at his large bay window and watched a team of men install security cameras along the outside of Alvarez's house. There had been a few old cameras before, but now there were better ones and a lot more — between nine and 14, depending upon whom you asked. Four or five were on the front of the house.

With its floodlights, tall perimeter gates, and the new surveillance system, the place looked like an embassy, neighbors joked. A police-trained German shepherd in the front yard was a final addition.

"What are you afraid of?" a trial attorney would later ask Alvarez's wife Betsy about those security upgrades.

"What am I afraid of?" she responded. "Of him killing us one day."

Mark Cantor had just walked his fluffy Wheaten terrier around the neighborhood. Now he was standing in his front yard, watching Alvarez sit in his idling Hummer in the street.

"He did that shit all the time when he'd see me," Cantor said. "Sometimes he'd follow me when I'd walk my dog, going nice and slow. I couldn't see him because his windows were so dark. It was intimidating."

It was January 2008, and the sun was just coming up. Cantor put his hand in his front pocket and then his back pocket. He moved keys around and hiked up his shorts. Then he gave Alvarez a dismissive wave.

The wave, Cantor said, was akin to "casting a spell." He meant to scare Alvarez in some half-humorous way but also to say, "Get outta here already." He lowered his hand to his back pocket again.

Alvarez sped off. Cantor took a shower and went to work.

That evening, as he was pulling his green Mini Cooper into his driveway, a police car jumped the curb behind him. Cops swarmed his yard. Cantor was arrested. Alvarez emerged from his house and patted officers on their backs.

One of the officers took Cantor to a police substation in Little Havana, where he recognized several of the cops from his takedown.

"We saw you on Alvarez's video, man," one of them said.

Cantor thought about the cameras along the façade of Alvarez's home.

"You pointed a gun at him this morning," the cop said. "You fucked up."

"I did what?!" Cantor asked.

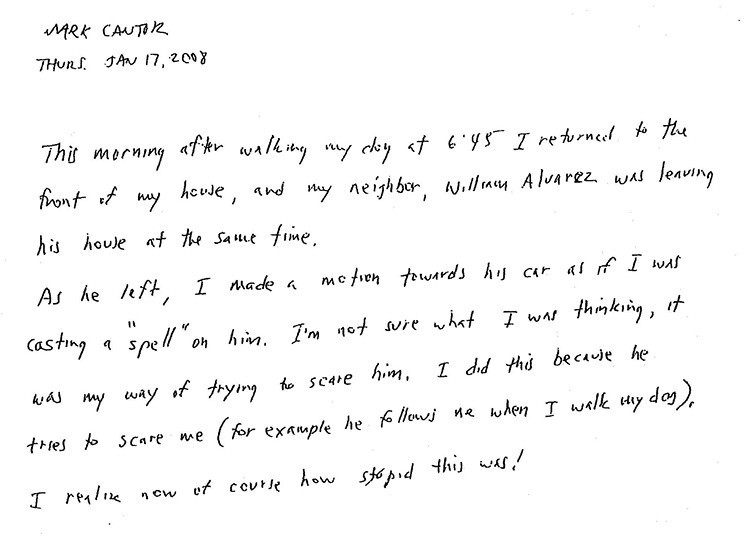

He apologized for making a hand gesture but insisted there was no gun. Why would he do that knowing there were cameras trained on him? The two detectives who interviewed him asked him to jot down a statement. He wrote:

"This morning after walking my dog at 6:45, I returned to the front of my house, and my neighbor, William Alvarez, was leaving his house at the same time. As he left, I made a motion towards his car as if I was casting a "spell" on him. I'm not sure what I was thinking; it was my way of trying to scare him. I did this because he tries to scare me (for example, he follows me when I walk my dog). I realize now of course how stupid this was!"

That night, Cantor shared a cell with about 50 other men at the Miami-Dade County Jail.

Cantor chatted up his cell mates, who were mostly young black men. They told him stories about being picked up every few months for things like open-container violations or a suspended license.

"What you in for?" one guy asked Cantor.

"Pointing a gun at a cop."

"Holy shit!"

As the night wore on, sleep was impossible. The benches and floors were covered in bodies. Cantor sat at a small picnic table and lay his head on his arms. The air conditioning was set so low everyone's teeth chattered. Every two hours, guards woke the men for a head count. Breakfast — powdered eggs and a stale biscuit — was served at 4:30 a.m.

At 8:30, all 50 men were taken to a drab basement room for their bond hearings. Cantor stood at a lectern, in front of a camera, and saw a judge on a TV screen.

"Who's the victim?" the judge asked.

Cantor could see only the judge, but he heard a familiar voice off-camera.

"I am," Alvarez answered.

He wondered how long he'd be homeless. It can't possibly be more than two months, he thought.

tweet this

Alvarez told the judge that Cantor had pointed what appeared to be a gun at him. He had video evidence to prove it. Also, he was a recently retired Miami Police commander and currently a reserve officer.

Cantor was charged with two felonies: aggravated assault with a firearm and aggravated stalking. The judge set his bond at $30,000 but lowered it to $7,500 when he learned no gun had been found on Cantor or in his car.

The judge also issued a "stay away" order requiring Cantor to keep 500 feet from the Alvarez family.

"How far is your house from Mr. Alvarez's?" the judge asked.

"About a hundred feet," Cantor said.

"Then you'll have to move out."

"Where am I supposed to go?"

"I don't know."

"When can I go back?"

"I don't know."

The judge told him to sit down and called the next defendant.

Cantor had 48 hours to collect his belongings from his house and secure the property. But he decided it was wiser not to go there at all. Instead, his ex-wife and his new girlfriend Jodie went to the house for him.

The two women had also posted his bond and found a lawyer to represent him. Cantor paid the attorney $10,000.

Meanwhile, he began sleeping at friends' homes or at his ex-wife's or girlfriend's apartment. Some nights, he dozed on the sofa in his office.

He wondered how long he'd be homeless. It can't possibly be more than two months, he thought.

Eleven days after his arrest, Cantor parked his car a block and a half from his then-vacant home.

It was 7:45 a.m. His 14-year-old son needed a book from the house for school. The boy's mother would've picked it up, but because she worked as a flight attendant, she was out of town. So Cantor drove his son to the house.

Cantor figured he was well beyond the 500-foot court-ordered perimeter. And he parked on a street Alvarez never used — it was too narrow for his Hummer.

"Just get your book and get out," Cantor told his son. "Don't worry — you're allowed to be there."

His son began walking. Ten minutes later, he reappeared with the book. Cantor saw a black Hummer stop at the top of the street behind his son.

The boy got into his dad's car. As Cantor was pulling away, Betsy Alvarez came around the corner in her Mercedes, pulled out her BlackBerry, and began taking pictures.

"Oh, my God!" the boy said to his dad as he slinked down in the seat. "You're going back to jail. It's my fault. We shouldn't have come here."

"Calm down," Cantor said. "We haven't done anything wrong." Then he dropped his son off at school and went to work.

At 10 a.m., two police officers arrested Cantor in front of his co-workers. They had seen Betsy's pictures, checked the distance on Google Earth, and walked the distance with a measuring wheel. He was, they said, a mere 200 feet from the Alvarezes' home.

Cantor was taken back to county jail. At his bond hearing the next morning, he appeared in front of Judge Larry Schwartz, a notoriously caustic judge.

His last bond hearing via video screen had felt impersonal, like a justice system assembly line. Now he was standing in an actual bond courtroom packed with defendants, families, lawyers, and cops. Everyone was anxious. It felt like a madhouse.

When Cantor walked to the lectern, Judge Schwartz said he had violated the stay-away order. That was another felony.

Cantor's lawyer tried to speak, but Schwartz cut him off. "It says on the police report that Mr. Cantor was 200 feet from the victim's house."

Cantor began, "That report was written by Mr. Alvarez's — "

"He's a cop," Schwartz interrupted. "I believe him."

This time, Cantor wasn't allowed out. Schwartz ordered him to be held in county jail until his preliminary hearing three weeks later. Cantor went back to his crowded cell. That night, he found a free spot on the concrete floor under a metal bunk.

His office sofa suddenly seemed luxurious.

Cantor's lawyer, meanwhile, used Google Earth and hired an investigator to measure the distance from the Alvarezes' home to the spot where Cantor said he parked and also to the spot where Betsy Alvarez had photographed him. Both were more than 500 feet away. Cantor might, however, have momentarily breached the perimeter by a few feet when he drove around a traffic circle at the end of the street.

He had spent $25,000 on legal fees and a few thousand more on visits to a psychologist.

tweet this

The lawyer scheduled a hearing with a new judge. Cantor, still wearing his office clothes from three days earlier, was handcuffed to eight other prisoners in orange jumpsuits and led to the courtroom. In the gallery, he saw nine co-workers from Frank Design. They had come to support him. He was touched but also embarrassed.

His lawyer presented maps to dispute the police measurements and explained Cantor had not gone to the neighborhood to engage Alvarez.

The judge agreed to release Cantor. The judicial system, however, moves slowly. Cantor spent a third night in jail and was released the next day.

That Monday, Cantor's lawyer asked for an additional $15,000 to handle the new charges. If Cantor wanted to go to trial, it could cost up to $50,000. Or he could skip trial altogether, avoid possible jail time, and get his record expunged by taking a deal that state prosecutors had offered. The deal included five things. He would:

1. not return home for eight months;

2. make a $250 donation to the Make-A-Wish Foundation;

3. write a letter of apology to Alvarez;

4. agree not to sue Alvarez or the City of Miami Police Department; and

5. submit to a psychological evaluation and undergo whatever treatment was deemed appropriate.

Cantor knew he could fight, but he had no money left and wanted to go home.

He took the deal.

Cantor spent the next several months living at his ex-wife's apartment. He had spent $25,000 on legal fees and a few thousand more on regular visits to a psychologist.

He missed his house. His teenage son, upset by the situation, moved to France to live with his grandparents. Now Cantor missed him too.

His psychologist, meanwhile, sent a letter to the court affirming Cantor's mental health.

The day when Cantor could return home finally arrived. It was October 2008, eight months after his arrest. He pulled into his driveway, and his heart sank. The property looked abandoned. Plants were overgrown. The lawn was ruined. Someone had tampered with his electrical wires and meter.

He began trying to get his property in shape, but it quickly became clear that was a mistake. Whenever he was there, Alvarez watched him from across the street. Sometimes he took pictures.

He rented the house to two young women who worked in his office and moved into his girlfriend's apartment in Kendall.

A few weeks after the women moved in, Cantor stopped by to do some quick yard work and run the sprinklers. His tenants weren't home, so he changed into a T-shirt and shorts in the garage and began piling up palm fronds near the curb so they could be picked up by city waste collectors the next morning.

Alvarez arrived home in his Hummer. It was dark, and Cantor stayed out of sight in the shadows. Alvarez, his son, and another boy glanced over at Cantor's car and then went inside.

Cantor stepped back into the light and began hosing down the driveway.

A patrol car pulled up.

Cantor shut off the water, sat on his back step, and called his lawyer.

"Stay calm," his lawyer told him. "Whatever happens, we'll handle it."

Cantor walked back to the front of the house. A police officer, standing on the sidewalk, called him over.

"Did you say anything to him?" he asked Cantor.

"Not a thing."

"Did you make any gestures?"

"I didn't even look at the guy."

A second cop was across the street talking to the Alvarez family. When that officer returned, Cantor, wearing dirty, wet clothes, was handcuffed and placed in the police car.

On the way to jail, Cantor asked the officers what Alvarez had said. They explained he was being arrested for threatening Alvarez.

"How did I threaten him?!" Cantor asked.

One of the officers read from the report he'd written based on Alvarez's statement: "Victim stated that the defendant started to make loud comments but [was] unable to determine what the defendant was saying. Then victim observed the defendant pick up a tree branch, held it at port arms, and started to make machine gun noises, then walked back to his house."

"Port arms?" Cantor asked.

The officer explained that meant standing with a rifle held diagonally in front of the body with the muzzle pointing up.

Cantor laughed. "And you believe him?!"

By now, the whole thing had become farcical. Cantor couldn't decide if he was in a nightmare or a Mel Brooks movie. He was booked back into county jail. In the morning, at the bond hearing, things got worse. He found himself, again, in front of Judge Schwartz.

"Everyone knows about you two and your childishness," Schwartz said when Cantor stepped to the lectern.

"I haven't done anything," Cantor said. "He keeps lying, and you keep believing him."

"I don't have any sympathy for you," the judge fired back.

Schwartz began asking questions. Cantor, whose lawyer was late, couldn't understand the legal jargon the judge was using. Schwartz grew impatient. Cantor asked if he could see a different judge. Schwartz sent him back to his cell.

The next day, his 55th birthday, Cantor returned to Schwartz's courtroom. "Don't play dumb with me today," Schwartz said. "You knew what I was asking you yesterday."

This time, Cantor's lawyer was there and got him moved to a different courtroom. Prosecutors re-charged Cantor with aggravated stalking and violation of a stay-away order and asked he be kept in jail for three weeks until his hearing.

The new judge took one look at the arrest report that described Cantor holding a branch at "port arms" and making "machine gun noises" and ordered Cantor released immediately.

Again, the system moved slowly. Cantor was transferred to Metro West Detention Center on the eastern fringe of the Everglades. His jail card had been lost, he was told, and he wouldn't get out until it was found.

The new judge took one look at the arrest report and ordered Cantor released immediately.

tweet this

His fourth day in custody, he was put in a van with two burly, heavily tattooed prisoners and transferred to Turner Guilford Knight Correctional Center near Miami International Airport. He sat in a cell there for the rest of the day without food or water.

At 8 p.m., a guard ending her shift opened the cell and told them they were getting out. Cantor said he needed to make a phone call. She said she had no time for that.

He was released wearing a blue prison uniform and paper sandals. His personal items were back at the first jail. He had no money. Nobody knew where he was. Out front, he asked passersby if he could use their cell phones. They just kept moving.

He couldn't walk to his house to get his car. The judge had issued a new stay-away order before releasing him. It didn't specify how many feet he had to keep between him and Alvarez, but Cantor thought, The farther the better.

He set out for his girlfriend Jodie's apartment in Kendall, where he'd been living. It was 17 miles away. As he began walking, he saw a familiar car approaching. It was Jodie. She had been making phone calls all day trying to locate him.

Cantor waved both arms over his head like a castaway. Jodie pulled up next to him. He climbed into the car and heaved a sigh of relief. It was five days before Christmas.

He had just one request: "Can we please go eat something?"

Orlando do Campo was a Harvard Law School grad with the demeanor of a bulldog, a proclivity for swearing, and a reputation as one of Miami's best criminal defense attorneys. In late 2008, he received a call from Mark Cantor, who told a strange tale: He'd been arrested three times and banished from his home because of allegations by a former police officer who lived across the street.

Cantor said he wanted to go to trial to fight the charges, but his current lawyer had told him it would be a mistake. As an Anglo accused of threatening and harassing a Hispanic family, Cantor wouldn't get a fair shake in Miami, where the judge and jury would likely be Hispanic, the lawyer said; he suggested Cantor make a deal.

Cantor disagreed. He asked do Campo to take a look at the case.

In truth, do Campo was used to frying bigger fish. As a federal public defender, he had helped fight charges brought by the U.S. government against the Cuban Five, who were accused of espionage. And he had worked on the case of José Padilla, accused of aiding Islamic terrorists. Now in private practice, do Campo preferred to work on a small number of high-profile federal cases.

Cantor's tale, however, sounded unusual. He agreed to read through the files.

Flipping through the pages, he grew perplexed. The plea agreement Cantor had signed after his second arrest stipulated Cantor could not sue Willy Alvarez.

Do Campo had never seen state prosecutors grant an individual that kind of immunity. It was routine for police departments to demand legal protection in plea bargains, but Alvarez had already retired from the Miami Police Department when that deal was formulated.

Do Campo called Cantor the next day. "This is bullshit," he said in his signature rasp.

"So, will you take the case?" Cantor asked.

"Yeah," he said. "You're being railroaded."

"Does this really need to go to trial?" Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Court Judge Antonio Arzola asked two years later in a final pretrial hearing. It was a Friday in December 2010, and Cantor's trial was scheduled for the following Monday.

Prosecutors said they'd done everything possible to persuade Cantor to take a plea bargain, including offering a year of probation and few other requirements. They urged the judge to make Cantor understand that if he lost at trial, he'd go to prison for a long time.

He was facing two felony charges: aggravated stalking and aggravated stalking in violation of a court order. Each carried a sentence of up to five years.

Do Campo turned to Cantor and gave him one last chance to reconsider. "Mark," he said quietly, "I'll do everything I can, but there are no guarantees. I'm going home next week. You might not. It's not a terrible deal they're offering."

Everyone looked at Cantor. He sat silent for what he would come to call "the longest 30 seconds" of his life.

He considered his losses. He had sold his home the previous year to help pay his legal expenses — and because he couldn't live there anyway. The real-estate market had crashed, so he got only $375,000 for it. In mid-2019, property websites estimated its value at nearly double that amount.

He had lost his job too. His partners at Frank Design said it had all become a distraction: the lawsuits, his arrest at work, sleeping in the office, and his loss of focus.

Now he was living at his girlfriend's apartment in Kendall and taking whatever freelance design work he could find. No one wanted to hire a man with his record. A Google search brought up his mug shots and charges.

Only a not-guilty verdict would clear his name. "I've never done anything to this guy," Cantor said. "I want to go to trial."

The judge flipped his folder closed: "See you Monday morning!"

The Richard E. Gerstein Justice Building in Allapattah is vintage Miami. It's a crowded beige 12-story structure from the 1960s where the city's cast of underworld characters faces justice.

Onto this stage in December 2010 walked Mark Cantor and his two-man defense team: Orlando do Campo and David Donet Jr. Donet was an old friend of do Campo's and a former Miami-Dade prosecutor who knew the state court system well.

The prosecutors, meanwhile, were two relatively young lawyers: Ana Manrara and Rebeca Quintero, both new to their jobs. The matchup seemed like a gift to Cantor's team. Besides, do Campo thought the state's case was flimsy. He figured it had been brought because Alvarez was a former cop.

Do Campo predicted an easy win. Cantor, he decided, didn't even need to take the stand. Generally, he liked defendants to testify. Juries don't always understand the right to remain silent. But this time he saw no need to "gild the lily."

First to testify, however, were the Alvarezes. Together, they presented a shocking picture of life across the street from Mark Cantor.

William Alvarez Jr., now 17 and a spitting image of his dad, began by describing how the ordeal began in 2005. It "was a very traumatic day," he said.

Cantor's son, Elias, had been trying to hit him with a stick. Then Elias hit himself in the face trying to dislodge a ball from a tree. William Jr. said he thought it was a funny kind of karma, so he laughed and told Elias he "deserved it."

Then Mark Cantor came and shouted at him.

"I got nervous, so I started to call my dad," William Jr. said. "I guess [Mark Cantor] was upset that I was calling my father, so he hits my hand, my right hand, knocking the phone out of my hand, and he calls me a little shit... and walks away."

“We were being harassed. My children couldn’t go outside and play with the rest of the kids.”

tweet this

Next came Betsy Alvarez, who cut a sympathetic image: an attractive, middle-aged, professional mother in a pretty dress with a crucifix hanging from her neck.

She said Cantor would constantly harass her family and shout "racist" remarks across the street. He'd say, "You Latin spic, you horrible Christian, go back to Cuba."

Betsy extended her arm in front of her. She called it the "Hitler gesture": "This was like a daily thing that he would do. Whenever he could see us, he would do that to us... He spent his whole life outside just watching us and obsessing over us."

As time passed, she said, things grew worse. Cantor followed her to work in his car. He would honk and glare at her as he drove by or lower the window and mutter things she couldn't quite understand.

On one of those occasions, she was almost nine months pregnant with her third child. She went into the office and cried uncontrollably. The stress of his constant harassment, she said, had already caused one miscarriage.

Even after a stay-away order was issued, Cantor didn't stop. The morning Betsy saw him in the neighborhood — when he claimed his son was retrieving a book from his house — he was parked only 200 feet from her house, she said. She wasn't able to take a picture until he had driven beyond the 500-foot perimeter.

"We were being harassed. We were being stalked," she said. "My children couldn't go outside and play with the rest of the kids on the block."

Her husband added cameras and flood lights to their property. They got a German shepherd. They bought cell phones for the kids so they could always be in touch. Ultimately, though, they were forced to sell their "dream home" to escape Cantor's relentless abuse.

Their house sold in March 2009, the lowest point of the real-estate market, for $740,000 — nearly $500,000 less than its estimated value in 2019. The five Alvarezes, including their 2-month-old, had to live in a one-bedroom apartment above their office until they were able to find a new home.

"Were you in fear?" prosecutor Ana Manrara asked Betsy.

"Yes," she said. "I'm still in fear."

"What are you afraid of?"

"What am I afraid of? Of him killing us one day."

When Willy Alvarez took the stand, he didn't look like a man who could fall prey to harassment or stalking. He was confident and solidly built and spoke in the no-nonsense style of a lawman. He confirmed the testimony of his son and wife, then unloaded a litany of other allegations against his former neighbor.

In April 2007, Cantor rang his doorbell late one night. Alvarez came out and told him for the "20th time" to stay away from his family. Cantor was irate, Alvarez claimed. He shouted, "Go back to Cuba, asshole."

A couple of weeks later, Alvarez was standing on the sidewalk in front of his house. Cantor backed his car out of his driveway and said, "Spic, you're dead," then drove away. A week later, the incident repeated.

"I was just shocked," Alvarez said. "I mean, it was just out of nowhere."

In October 2007, Alvarez was heading to Key Biscayne on his bicycle to train for a triathlon. Cantor "zoomed up" next to him in his car, revved his engine, and then drove off, the former cop said. Cantor reappeared beside Alvarez on a different street and shouted, "Spic asshole, go back to Cuba." He did the same thing again on a later date and even forced Alvarez off the road.

That month, while sitting on his front step, Cantor called over William Jr., who ignored the invitation. After Alvarez warned Cantor to quit bothering his son, Cantor yelled, "You're going to have to shoot me to make me stop."

The comment made Alvarez nervous. He knew what guns could do. "That tragedy could go either way — me get killed, him get hurt," he testified.

Four days later, Alvarez went to the Domestic Violence Criminal Court in downtown Miami. He wanted a judge to issue a restraining order against Cantor.

The request was denied. He had retired from Miami PD a few months earlier. A clerk handed back his application with instructions about what he should do: "Call the police."

Some defense lawyers like to play coy with the facts. Others go on the attack. Do Campo, with an entertainer's gift for dialogue and a brown bow tie around his neck, did both.

He already knew about the bigotry allegations against Cantor. He also knew Alvarez had filed police reports after each alleged incident. Those issues were the reason the previous lawyer didn't think Cantor, as an Anglo in a majority-Hispanic town, stood a chance at trial.

But do Campo was suspicious of the allegations. There were no witnesses to Cantor's behavior. Despite all of Alvarez's cameras, there were only three videos of Cantor; they had no audio and showed nothing that was clearly incriminating. And all the incident reports about Cantor's behavior were filled out by Alvarez's former subordinates, colleagues, or friends.

Incident reports simply record one person's version of an alleged crime. They are passed to senior officers and then assigned to detectives, who determine if a crime occurred. To do that, they usually gather evidence and track down suspects and witnesses. At the very least, they make phone calls to get additional statements.

None of the reports filed by Alvarez, however, followed that track. There was no followup, and Cantor was never contacted. Consequently, Cantor had no idea a file accusing him of harassment, bigotry, and stalking was building.

On the stand, do Campo questioned Alvarez about the incident when Cantor allegedly tried to run him off the road. "It could be considered an aggravated assault with a deadly weapon," he said, "even attempted murder."

"That is correct," Alvarez said.

So why was there no followup, do Campo wanted to know.

"We never pushed the issue because we were leery of arresting him," Alvarez said. "We just didn't want it to get worse."

But do Campo pointed out the commander of the Roads area, where all of the alleged incidents occurred, was Ron Papier. Alvarez and Papier were good friends who chatted on the phone once a week. Papier even supervised the officers who took several of Alvarez's reports.

Moreover, the restrained approach to dealing with Cantor seemed to contrast with the assertive persona for which Alvarez was known. On the stand, he asked questions instead of answering them, made flippant remarks, and accused do Campo of lying. At one point, the judge admonished him: "Don't talk back."

The testimony was clear: Cantor did not slap a phone out of the boy’s hand.

tweet this

Do Campo argued that Alvarez was simply hell-bent on exacting revenge on Cantor for allegedly hitting his child and filing a complaint against him with internal affairs. Alvarez knew he had to show a history of threatening behavior to persuade a judge to issue a stay-away order that would remove Cantor from his home.

"Sir, isn't it a fact that you didn't want anybody to contact Mr. Cantor about [your allegations]?" do Campo asked.

"Why is this?" Alvarez asked.

"Because you were laying a paper trail showing a repeated pattern of activity."

Alvarez was stern. "That is not true."

Do Campo played the video that led to Cantor's first arrest.

Alvarez said it showed Cantor possibly pointing a Wallet Derringer — a small gun — or perhaps just simulating the firing of shots. Either way, it was a threatening move that led Alvarez to fear for his life.

The video was grainy and black-and-white due to the lack of light in the early morning. Leaves from an overhanging branch partially obscured Cantor's raised hand.

"Clearly, he has nothing in his hand," do Campo said.

"It's not 'clearly,'" Alvarez retorted.

Do Campo played the second video that Alvarez had presented as evidence. It captured Cantor allegedly shouting across the street: "You're going to have to shoot me to make me stop."

The footage showed Cantor sitting on his front step. There was no sound, but Cantor's mouth was moving. He appeared to be arguing with someone.

But Alvarez's camera was zoomed in so close that only Cantor was visible on the screen. What the footage didn't show, do Campo said, was Alvarez antagonizing Cantor from across the street, intentionally winding him up for the camera.

"I have my other camera showing me," Alvarez said.

"But we don't have that footage, do we?"

"I don't know why because I supplied it."

"Really? I guess the state just didn't use all this video that you gave them. Is that your testimony, sir?"

"I don't know what happened."

Do Campo then played another video, which Alvarez said showed Cantor pointing a stick at his family in a threatening manner.

Do Campo said it simply looked like a man heaving a large branch into a trash pile.

Alvarez balked. "He pointed it just to bother us, and that's the constant harassment that me and my family was subjected to all this time."

Again, Alvarez said he had additional videos that prosecutors didn't use and he didn't understand why.

"I want to end it right there, judge," do Campo said.

The state rested its case after Alvarez's testimony. Do Campo and Donet, however, had lined up more witnesses.

They called Cantor's former neighbor, Ana Pita, who had been standing right behind William Jr. when Cantor confronted him in 2005 and witnessed what the judge called "the genesis of the whole nightmare."

Pita was reluctant to get involved. After the incident, she told the Alvarezes it all happened so fast she wasn't sure of the details.

Now, though, her testimony was clear: Cantor did not slap a phone out of the boy's hand. He didn't lay a hand on him.

Next came the character witnesses: three Hispanic women who were Cantor's friends and former colleagues. One was a dean at Miami's New World School of the Arts. The second was a fundraiser at the American Cancer Society. The third was a professor at Miami Dade College.

Do Campo's question to all three was the same: Did Mark Cantor have a reputation for being a bigot?

No, no, and no.

Prosecutor Manrara asked whether they had ever seen Cantor interact with his neighbors. They had not. Bigotry is bad for business, Manrara added, and people sometimes wear different masks in different settings.

Do Campo asked the last character witness just one question: "Do you know what Mr. Cantor's religion is?"

Manrara objected, and the judge sustained.

To Cantor's allies, it was a mind-boggling legal twist. Cantor had been accused of regularly using the Nazi salute to taunt his neighbor, but his lawyer was not allowed to introduce what might have been the most telling detail of all.

Cantor is Jewish.

In her closing statement, Manrara referred to the witness who said Cantor did not hit William Jr. in 2005: "Who cares? He's not charged with battery."

The charges were two felony counts of aggravated stalking. One was for Cantor's alleged behavior before a stay-away order was issued. The second was for the period afterward. If jurors believed he was guilty but didn't pose a credible threat, they could find Cantor guilty of misdemeanor versions of each charge.

But the threat, Manrara said, was very real. Cantor couldn't contain himself. "This is a man that sits on his front porch and just starts yelling and raising his hand at these people. He has no control. He had absolutely no control, casting spells, saying 'spic.'"

As for Willy Alvarez, if he was such a "big, bad cop," Manrara said, why didn't he get Cantor arrested for all of the confrontations? He could've asked prosecutors to file charges. He could've planted a gun on Cantor's property.

While Manrara offered a well-packaged legal argument and polished presentation, do Campo displayed a casual relatability. He told a tale of an Everyman unjustly smeared by a vindictive cop.

It had all begun, he said, with a lie.

For reasons we'll never know, do Campo said, William Jr. accused Mark Cantor of hitting him. Perhaps the boy exaggerated. Perhaps his mother took his story out of context. Now, at 17 years old, he had no option but to maintain the lie.

"Little William Alvarez, ladies and gentlemen, he loves his dad...," do Campo said. "Of course he's going to defend his father. What choice does he have?"

Do Campo slapped his own hand as hard as he could and held it up. "And, by the way, hitting and slapping like that is not going to leave a red mark that's going to last for a half-hour."

A day later, the jury deadlocked. Four wanted to acquit; two couldn’t decide.

tweet this

That lie, he said, prompted Alvarez to march across the street in his police uniform and verbally assault and threaten Cantor. After Cantor filed a complaint, Alvarez made it his life's mission to destroy him. "And destroy him, he did."

Was it really logical that Cantor had approached "the SWAT commander, Commander Alvarez, and [told] him: 'You're dead, spic'?... Where does that even make sense?"

And "'stupid Christian'?" he asked, quoting Betsy Alvarez. "Who ever even heard somebody say something like that?"

In the end, Alvarez sank himself with his cameras, do Campo said. He spent thousands of dollars to monitor Cantor round-the-clock, and what did he capture? Three short clips that only illustrated Alvarez's knack for misconstruing innocuous behavior as dangerous threats.

It's "nonsense," do Campo said of the Alvarezes' allegations. "They're not on the same planet."

Cantor and his team awaited a swift acquittal on all charges. "We crushed them," do Campo thought.

A day later, the jury deadlocked. Four wanted to acquit; two couldn't decide.

Do Campo was "mortified." He re-examined his every move. If the state planned to retry the case, he realized, he'd have to do one thing differently.

Mark Cantor must testify.

Three months later, a new jury was convened. The state could've dropped the case. Instead, two new prosecutors, more senior than the last, took over. They were Jennie Conklin and Ignacio Vazquez Jr.

After a jury was chosen, Betsy Alvarez took the stand. Again, she described Cantor's harassment, ethnic slurs, and Nazi salutes. Again, she said she had to sell her home to get away from him.

At the first trial, do Campo had found something odd about the claim that Cantor drove the Alvarezes out of their home, but he didn't press the issue. Now, though, he had new information.

He pointed out that Cantor had not lived across the street from the Alvarezes for two years when they sold their house. Also, Cantor had sold his home at nearly the same time as the Alvarezes.

Also, the Alvarezes' new home, which they bought just a few weeks after selling their old one, was a new, 5,400-square-foot waterfront house that clearly outdid their previous place. Property websites in early 2019 estimated its value at $4 million.

"Isn't it a fact," do Campo asked Betsy, "that you sold your home in the Roads and within a few weeks bought a mansion on the water? That your old house was 3,000 square feet and your new one is nearly double?"

Betsy seemed to panic. "You know where I live?" She pointed at Cantor. "That means he knows where I live!" She started to sob.

Do Campo called for a mistrial. It was an act, he said. She was laying it on thick to manipulate the jury.

The judge ended the trial 30 minutes after it began.

The next morning, Cantor and his lawyers showed up prepared for trial number three.

Before proceedings could get underway, however, the prosecutors made an announcement. They were adding an additional charge of aggravated stalking for acts committed against Betsy Alvarez, bringing Cantor's total number of felony charges to three.

They also dropped a bombshell. They were adding a hate-crime enhancement to two of those charges, increasing the punishment for each. Cantor now faced up to 30 years behind bars.

Cantor and his lawyers were appalled. To prove a hate crime, prosecutors had to show a defendant had selected a victim because that person belonged to a certain group. Cantor, his lawyers argued, clearly hadn't done that.

"It was inconsistent with the theory of the case," do Campo said. It was also "a dirty, lowdown thing to do."

Do Campo had zero experience with hate crimes. He asked the judge to delay the trial so he could prepare to fight the new charges.

Cantor's first attorney might have been right. Maybe Cantor didn't stand a chance at trial.

"It's comical," Mark Cantor said of the Alvarezes' allegations.

It was October 2012, nearly two years since his first trial, and he was finally on the stand at his third.

The prosecution team had been upgraded once again. Jennie Conklin remained, but her new partner was Richard Scruggs, who usually handled high-profile state corruption cases. The judge referred to him as "the big gun."

Willy and Betsy Alvarez had already testified. They talked about their constant fear and Cantor's threats.

"He would raise constantly the neo-Nazi sign like this, which is a very offensive sign," Willy Alvarez said. "Basically, it's a racist sign. Skinheads use that." "He would call us spics," Betsy said. "He would call me 'asshole Christian.' He would say, 'Go back to Cuba.' He did the Nazi salute to us, like, all the time."

Cantor's religion, immaterial at his first trial, was admissible now that he was testifying in his own defense.

"Do you have a particular hatred towards Christians?" do Campo asked Cantor.

"No, not at all. My ex-wife is Catholic; my grandfather was Catholic. I have a lot of Christian relatives."

"What is your religion, sir?"

"I'm Jewish."

"Are you fond of making the Nazi salute, sir?"

"No, that's like the most insulting thing that Alvarez has said. I can't even give an answer to that."

Then do Campo asked, "Have you ever called anyone a spic?"

"I don't use that kind of language."

Cantor, in a stylish blue suit and matching blue tie seemed oddly relaxed on the stand. He admitted to just one of Alvarez's accusations. He had rung his doorbell one evening and called him an asshole.

Cantor said Alvarez had come home in an unmarked police car and forgot to turn off the headlights before going inside. "I said to myself, I'm going to show him I'm not such a bad guy; I'm going to tell him his lights are on. Big mistake."

Alvarez came out in a rage, Cantor said. "He was like, 'What the fuck are you doing on my side of the street?!' He just kept screaming, screaming, screaming... I said, 'You're such an asshole — I came over to tell you your lights are on.'"

"Did you ever follow Betsy to work?" do Campo asked.

It was impossible to avoid her office, Cantor said, because it was on Coral Way, the neighborhood's main thoroughfare. It was also near a ramp to I-95. Sure, she might have seen him nearby, but he wasn't following her.

"Did you ever tell them to move back to the place where they came from?" do Campo asked.

"I never said that to anybody," Cantor said.

"I have nothing further."

"So you're really the victim here?" prosecutor Jennie Conklin asked Cantor.

"Yes," he said.

"Did you ever try to keep a notebook of the things [Alvarez] would do to harass you to protect yourself?"

"I don't think like that... I have no bars on my windows; I have no cameras on my house."

So, she asked, "pretty much Willy created all these incidents?"

"Yeah."

"Just to harass you?"

"Absolutely."

"To get back at you?"

"Exactly."

On the fourth and final day of trial, Judge Antonio Arzola entered a directed verdict dismissing the hate-crime enhancements on Cantor's charges. The prosecution, the judge said, had failed to meet its burden of proof showing Cantor acted out of prejudice.

To Cantor, it was a minor reprieve. Three felony stalking charges, carrying up to 15 years in prison, remained.

Prosecutors Conklin and Scruggs took turns delivering the state's closing argument.

Was it believable that Alvarez could lie so consistently for so long?

tweet this

Conklin likened Cantor's "unending torrent" of name-calling and his "campaign of harassment" to death by paper cuts. "One paper cut, you can get past. You live with it," she said. "Twenty paper cuts, that really kind of hurt. Forty paper cuts, it hurts even more."

Scruggs, meanwhile, focused his argument on exonerating Willy Alvarez.

To believe Cantor, he said, one had to believe Alvarez committed perjury — that he lied to the court, lied to get a stay-away order, lied to prosecutors, lied to the police for years to create a paper trail.

One had to believe that Betsy, too, lied — that she wasn't really afraid or upset.

Then one had to believe the two of them rehearsed so their stories would match — all so Willy Alvarez could take vengeance on Mark Cantor.

"Oh, my God," Scruggs said sarcastically. Mark Cantor is basically "the victim of... a massive... criminal conspiracy... to frame and convict an innocent man."

His argument hit on the case's core dilemma: Was it believable that Alvarez could lie so consistently for so long?

Do Campo focused in his own closing argument on Alvarez's personality.

"You saw him," do Campo said. "He was constantly speaking over me, over the judge, wanting to lecture you directly, not answering the questions, giving speeches."

Could the jury really believe Alvarez was petrified of Mark Cantor?

Cantor, do Campo said, was the one being stalked. "How would any of us feel if a camera was pointed at our front door, zooming in and watching all our movements. I mean, it's creepy."

Ultimately, though, Alvarez's cameras were his undoing, he said. Willy and Betsy claimed Cantor had harassed them continually for years.

"There should be dozens of videos, dozens, hundreds maybe," do Campo said. "Where are they? These three puny videos, that's the evidence they have despite that investment?"

Do Campo conceded Cantor had acted badly when confronting Alvarez's son in 2005.

"I don't know that I necessarily approve of that," he said. "Maybe the smarter thing would have been to go and talk with his parents, maybe even just let it go."

But look at the price Cantor had paid, he said: arrests, years of legal trouble, a tarnished reputation, and a drained bank account. The Alvarezes moved to a mansion on the water. Cantor still lives in his girlfriend's apartment in Kendall.

In the end, do Campo acknowledged the trouble jurors might face trying to decide the case: "Some of you may think, I don't know who to believe."

That, he explained, is a reasonable doubt. And if there's doubt, a jury must find Mark Cantor not guilty.

This time, jurors had no doubt. They deliberated for just 30 minutes.

The courtroom was full for the reading of the verdict. There were Cantor's friends and colleagues, the two young prosecutors from Cantor's first trial, and court employees whom he had come to know on a first-name basis along the back wall. Notably missing were the Alvarezes.

The verdict: not guilty on all charges.

When Cantor left the courtroom, all six jurors were waiting for him. They took turns shaking his hand.

Cantor kept waiting to feel something — satisfaction maybe, or at least closure. Instead, he just felt depressed.

He called the psychologist whom he had been ordered to see after his second arrest. Cantor wasn't his patient anymore, but they were now friends. "I beat the charges," Cantor told him, "but I don't feel like I won."

"Because you haven't actually won anything," his friend replied.

Cantor hung up and called Orlando do Campo. "I want to take Alvarez to civil court."

"Let it go," do Campo said. "You don't want this guy in your life anymore."

But Cantor had lost too much financially and personally.

John Thornton, a civil litigator who works with do Campo, filed a civil complaint on Cantor's behalf December 17, 2012. The lawsuit seeks damages against Willy and Betsy Alvarez for conspiring to cause Cantor's false arrest and prosecution and for infliction of emotional distress.

How much does Cantor want?

"My lawyer hasn't really given me a number yet," he says. But, he notes, Alvarez receives a substantial police pension, owns multiple properties, and is a successful real-estate broker.

Alvarez, though, is not slinking away in defeat. He sought the services of Coffey Burlington, one of Miami's most prominent law firms, and responded with a countersuit that contains the same allegations as the state's failed criminal case. It calls Cantor's lawsuit "harassment."

"Because of prejudice, envy, or some combination of the two," it reads, "Cantor decided to turn the Alvarezes' life into an unrelenting ordeal." Alvarez is also seeking an unknown amount in damages from Cantor.

For the past seven years, the men's civil lawsuits have been mired in legal wrangling. A trial date has yet to be set.

"I call my layers all the time to ask what's going on," Cantor says. "They have hearings. I don't go to them. Alvarez goes to them because he's the one fighting me now."

“Mr. and Mrs. Alvarez strongly deny any allegations of impropriety asserted by Mark Cantor.”

tweet this

Troubling questions remain: Did Alvarez make it all up? Was it delusion? Paranoia? Was the feud just a testament to the lengths people will go to get even? Was Cantor telling the whole truth?

Sitting at a Starbucks near his old Design District office in mid-2019, Cantor addresses that last question. "Honestly," he says, "I never even gave the guy the finger. Why would I do that? He's a cop. He's a SWAT team commander. I'm not looking to engage the guy."

Cantor says he would sometimes wave sarcastically to Alvarez. Other times he would wave him off. He marvels at the ignorance of accusing a Jew of the making Nazi salutes. "My dad fought in World War II," he says. "It's offensive."

Alvarez didn't reply to an interview request, but his lawyer provided the following statement: "Mr. and Mrs. Alvarez strongly deny any allegations of impropriety asserted by Mark Cantor."

A follow-up request asking for the names of witnesses to Cantor's behavior or additional evidence went unanswered.

Today, Cantor works as a graphic designer at one of the largest Cuban-owned companies in Miami. He still lives with Jodie in Kendall. They're engaged now, but there won't be a wedding until the civil suit is over. Marriage would expose her assets if Alvarez prevailed in civil court.

They won't buy a house for the same reason. The contents of Cantor's old home, meanwhile, have been collecting dust in storage for a decade.

"Everyone I know is moving on with their life, and I'm still hung up," he says.

Meanwhile, he's taken a page out of Willy Alvarez's playbook. "I have cameras in my car now," he says, "a dashcam that films forward and backwards so you can see me. And it has GPS so if Alvarez says I drove past his house, 'Nope. I was in Doral. Here's the video and the time stamp.'"

Still, he worries about how easy it would be to wind up back in jail and facing new charges. A setup isn't that hard. Someone could plant a gun under his car seat or file a new report alleging criminal behavior.

Would anyone believe him the next time around?

"I don't want to find out," he says.