Photo by Jerry Iannelli

Audio By Carbonatix

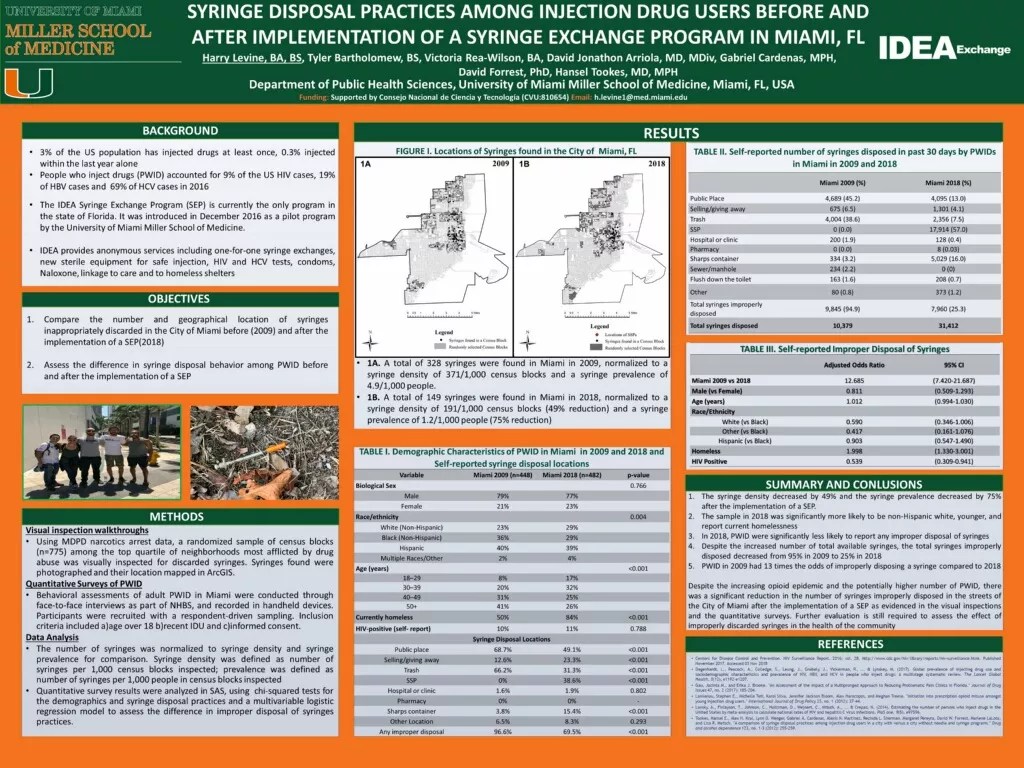

The University of Miami’s Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) Exchange gives clean syringes to heroin and opiate users as long as they deliver dirty needles to the clinic. The program gets used needles off the street and cuts overdose rates as well as disease transmission.

This is vital. Miami is the most HIV-ravaged city in America, with twice as many HIV-positive residents – 47 people for every 100,000 – as San Francisco, New York, or Los Angeles.

But try telling that to City of Miami Human Services director Milton Vickers and Miami-Dade County lobbyist and Homeless Trust chair Ron Book. For nearly two hours at county hall yesterday, they launched a series of misinformed, dangerous, and shameful questions at the doctors, cops, judges, health department officials, lawmakers, and parents of deceased addicts who have organized, operate, and support the IDEA Exchange.

IDEA Exchange director Hansel Tookes and others are concerned the attacks could kill or substantially harm the program. Although the doctor, a Yale graduate whose work has garnered honors from across the nation, explained the ways the needle exchange saves lives, Vickers and Book contradicted and shouted over him.

“Please do not let your hatred of me harm an entire population,” Tookes said to Vickers during the meeting. The dialogue elicited gasps in the room.

The meeting was a top-to-bottom embarrassment – city and county officials displayed a startling lack of knowledge about how the program operates. The event was also a perfect microcosm of the debate now playing out nationwide. Doctors and therapists overwhelmingly say

Earlier this year, Philadelphia created “safe-injection sites” where addicts can safely use opiates while being monitored by professionals, who also work to find treatment for users. The Trump administration has sued the city to prevent the creation of those sites. Health professionals say the Department of Justice’s lawsuit will lead to more dead heroin users.

The Florida Legislature approved the IDEA Exchange in December 2016 after three years of lobbying from Tookes and other proponents. Its workers dispense syringes from a location at 1690 NW Seventh Ave. Though the program is regulated by the state, it’s funded by a patchwork of private donors and costs about $500,000 per year to operate.

Doctors dispense needles from a mobile van, the office, and from backpacks. Addicts are routed to treatment. And it has worked. Opioid deaths are dropping in Miami, as is the transmission of HIV. Earlier this week, the IDEA Exchange released data showing that

Tookes initially endured some harassment from the City of Miami Police Union; former union president Javier Ortiz attacked the exchange online in 2017 for allegedly “enabling” addicts, and Tookes told the Miami Herald that cops had visited the exchange and threatened to arrest any users coming in for free needles or drug treatment. But since then, Chief Jorge Colina and other officers have supported the program.

Now lawmakers – including Miami-Dade state Sen. Oscar Braynon and Hollywood state Rep. Shevrin Jones, both Democrats – are attempting to pass a bill that would allow each county in Florida to create an exchange program. A similar measure failed in Tallahassee last year. (Book, at least, seemed as if he might’ve come around on the issue by the end of yesterday’s meeting.)

Speaking by phone later yesterday afternoon, Tookes told New Times he’s confident lawmakers will understand the value in expanding his program statewide. But he implored Vickers not to lobby any other city or state officials against the program.

“The thing that was most incredible about that, in addition to having bill sponsors, we had the Florida Department of Health, Miami [Police Department], judges that have dedicated their careers to this stuff, all on the same page that the needle exchange is an essential part of the response to the opioid epidemic,” Tookes said. “They know it’s not a cause of the epidemic, not a reason there are homeless people in Miami. Everybody was aligned.”

University of Miami IDEA Exchange

Vickers is among the city’s loudest critics. He has summoned doctors to repeated meetings and contacted state lawmakers to sink efforts in Tallahassee. New Times has also obtained an email Vickers sent City of Miami staff February 6 complaining the city has been “left with the consequences” of the exchange and demanding it be given the ability to “choose not to participate at any point in the Program.” He also implied the exchange was responsible for discarded syringes:

It is recommended that the City position on the Needle Change expansion should address the concern and experiences of City of Miami Staff.

- Syringes found in parks

- Syringes found on Public School Playgrounds

- Discarded syringes found on public side walks

- Discarded syringes found in large quantities in opioid encampments

Vickers doubled down on his statements at yesterday’s meeting, suggesting that, if the needle exchange is allowed to continue, it should be required to protect the city from future lawsuits. He also suggested IDEA Exchange syringes be labeled so they can be traced. And Vickers pushed the exchange to install safe-disposal boxes around the city’s problem areas, something Tookes had already begun doing prior to the meeting. (At one point, Vickers even lied by saying Tookes had failed to communicate with his office. The doctor then forwarded emails to reporters showing this claim was untrue.)

Doctors and advocates informed Vickers that no other syringe-trading program in America labels its needles because the cost would be astronomical. Also, misinformed critics would likely use the labeled syringes to attack the program.

Vickers repeatedly claimed he does not hate the exchange and wants it to exist. But he also listed a series of cases in which addicts have left syringes in parks or playgrounds. He implied the problem was somehow the fault of the needle exchange even though he had no evidence to back up his point. For example, Vickers mentioned one recent public meeting in Overtown where a local resident left a syringe behind – but Vickers did not actually say where the needle came from.

“There was a gentleman who stood up to speak, was out of order, the chairman would not allow him to go forward, but when he got up to walk out of the room, he left a syringe in his seat,” Vickers said. “The chairman walked over, grabbed the syringe, and clearly said, ‘This is what we don’t want to see in our community.’ We cannot be nonresponsive to that.”

Senator Braynon, who attended the meeting, eventually cut Vickers off by claiming the bureaucrat seemed to be blaming the needle exchange for random syringes left around town. Braynon, Deputy Miami-Dade Mayor Maurice Kemp, and multiple doctors stated the problem was actually worse before the exchange existed.

“You keep saying, ‘It’s your fault,’ without actually saying, ‘It’s your fault,'” Braynon said.

(After the meeting, Vickers denied he’s simultaneously claiming he likes the program and requesting the ability to cut ties with it. New Times then asked if he’d ever try to shut down the program. “More than likely not,” he said.)

Über-lobbyist and Homeless Trust chair Ron Book also pushed back against the needle exchange. Book, a lobbyist for Miami-Dade as well as private-prison firms and medical associations, chairs the county’s homeless-outreach group despite having little background in medicine, social work, or therapy. Just last weekend, he was arrested for allegedly drunk-crashing a Lamborghini on a Broward County highway and refusing a police Breathalyzer test. (This was not Book’s first run-in with law enforcement.)

Yesterday was Book’s first public appearance since his most recent arrest. He arrived late, paced around the room, and conducted private conversations while other people were speaking. In his classic loud style, he shouted over other people in the room and spent upward of ten minutes complaining about alleged “opioid sex camps” in downtown Miami and Overtown that have nothing to do with the needle exchange. He also asked whether the needle exchange “encourages” drug use (which elicited a groan from almost everyone present) and questioned whether a needle exchange worsened the opiate crisis in Philadelphia. (The opposite is true.) Then Book questioned the “integrity” of the exchange and asked whether the program is giving out more needles than it should.

Even two parents of deceased addicts – Joy Fishman and Cindy Dodds – called the program a success.

Dodds lost her son Kyle in 2016. He was on his way to work when he stopped in Overtown, bought drugs, snorted them, and immediately overdosed. At yesterday’s meeting, Dodds said that thanks to Tookes’ program, discarded syringes have virtually disappeared at the site where Kyle died.

“It’s working,” an exasperated Dodds told the panel yesterday. “I can’t tell you enough.”