Photo by Jess Swanson

Audio By Carbonatix

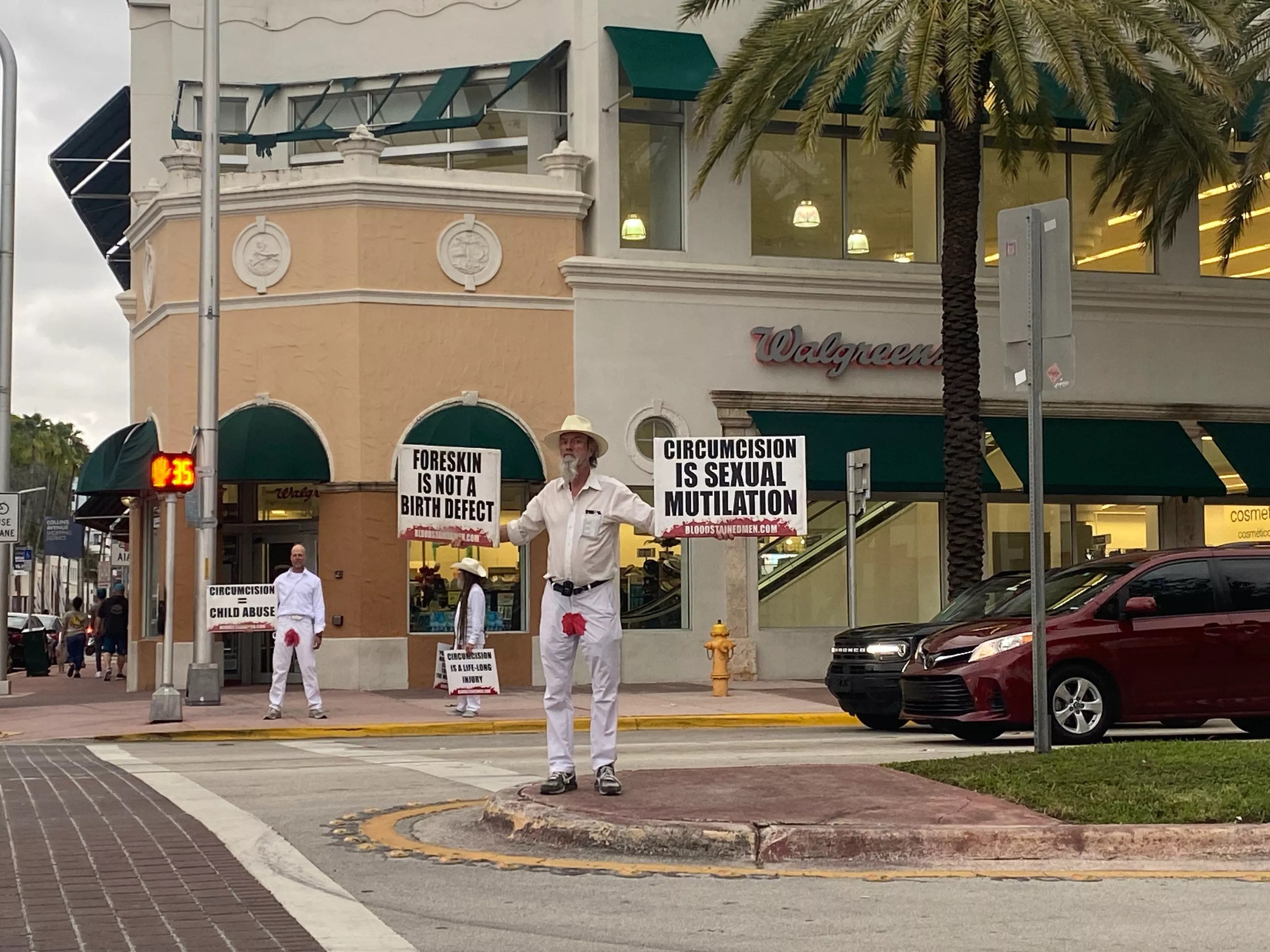

David Atkinson wants his foreskin back. In his right hand, he holds a white sign spattered with red ink that says as much; a similar sign in his left hand reads “CIRCUMCISION ANGUISH.” He’s dressed in a white cowboy hat, white bandanna, white button-down shirt, white sneakers, and white pants that bear an unmistakable red stain on the crotch.

“It represents the wound inflicted on us when we were too young to defend ourselves, and in most cases by American doctors,” Atkinson says of the stain. “When you permanently amputate part of the genitals of a newborn baby, you are permanently amputating part of the genitals of the man who he will become and who might have wanted to keep all of his penis.”

Atkinson is president of Bloodstained Men, a nonprofit that seeks to give “victims of genital cutting a voice” and to educate Americans about the harms of infant circumcision and the anatomical importance of the foreskin. On this last Friday afternoon in January, he’s one of seven circumcised men dressed in the group’s signature all-white getup with identical trouser stains commanding the intersection at Collins Avenue and Fifth Street in Miami Beach. For more than an hour, they hold up signs and banners and distribute pamphlets and bumper stickers with slogans like “Circumcision ruined the hand job.” Most passersby avert their eyes to avoid falling prey to a spiel. But some drivers honk in solidarity, and one gentleman rolls down his window to raise a fist in support of the movement. A gregarious and inebriated gaggle of Brits cheers, shouting “Fucking barbaric!” and Only in America, mate!”

“From a South Florida perspective, we have a fairly international community down here and routine infant circumcision has been primarily a phenomenon of the Anglo culture. It has never been a phenomenon of Latin culture,” explains Hollywood resident and “intactivist” John Ellis. “Unfortunately, we have a bit of an uphill battle to fight, because in this part of the world, people don’t want to admit that we’ve done a wrong thing for a long time.”

Bloodstained Men commanded the intersection at Collins Avenue and Fifth Street in Miami Beach on Friday afternoon.

Photo by Jess Swanson

Bloodstained Men have organized 26 protests over two weeks across Florida. Earlier on Friday, they gathered at North Kendall Drive and 137th Avenue in Kendall and at SW Eighth Street and 107th Avenue near Florida International University’s Modesto Maidique campus. A day prior, they were in Key West and Marathon. Over the weekend, they’d move on to Pembroke Pines, Pompano Beach, Boynton Beach, and Jupiter, then on to Vero Beach, West Melbourne, Port Orange, Orange City, and Orlando. A billboard they purchased on northbound I-75 near Ocala reads, “Circumcision Cruel & Harmful.”

The Bloodstained Men and their supporters in Miami Beach

Photo by Jess Swanson

“I have had pain in my penis my whole life that I thought was normal. I found out it was called amputation neuromas from when the nerves were severed,” protester Daniel Bryce says. “I was waiting until my parents passed away before I did my research into it because I was afraid I would be livid with them – and I am livid with them.”

Bryce crosses his arms to reveal two tattoos, one on each forearm: “Victim of Circumcision” and “MGM Survivor” (a reference not to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer but to Male Genital Mutilation.

Bloodstain Men member Daniel Bryce reveals his tattoos.

Photo by Jess Swanson

Less than two years ago, Bryce started “foreskin restoration,” a tedious, yearslong process that employs various contraptions to regenerate a sliver of skin on the penis as one might stretch their earlobes for gauges. The undertaking can be isolating, and most men “restore” in private without informing loved ones or doctors and consult online forums for guidance.

But on this Friday afternoon, Bryce can speak openly about the process. In fact, a fellow protester chimes in that he too is wearing a restoration device under his crimson-stained pants.

By his late 40s, Bryce says, he could not achieve an erection, which he attributes as a direct consequence of his circumcision. Since he began restoring, Bryce reports better sensation, more lubrication, and more-pleasurable sex.

“Within two hours of putting on [the foreskin restoration] device, the lifetime pain that I had disappeared,” he declares. “Restoring is empowering. It does feel like you’re regaining some autonomy.”

A man who goes by his Instagram and TikTok handle @AuthorMiamiRich, stops to chat with the demonstrators, listening to their message for more than ten minutes.

“This kind of blew my mind. Never in my 46 years have I even thought about circumcision, nor have I ever seen anybody speak out against it,” he tells New Times. “I’m a natural kind of guy and this sparked a thought in my brain. It kind of woke me up, and now I’m kind of mad that I circumcised my son three years ago.”

Circumcision has been found to reduce the risk of urinary tract infections, penile cancers, and other health conditions. But, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, the benefits aren’t sufficient to recommend the procedure universally. A 2013 study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that circumcision was on the decline in the United States; in 2010, approximately 58.3 percent of male newborns were circumcised during their birth hospitalization. In Western Europe, circumcision rates of minors are under 20 percent. In 2019, the New York Times reported that in the Middle East, where Islamic and Jewish religions promote circumcision, the rate can reach 95 percent.

“I love that I’m circumcised,” one passing passenger shouts through his rolled-down window. “What you’re saying is anti-Semitic. What do you have against Jews?”

Atkinson shakes his head. “Occasionally there are people who will make false, disingenuous claims of anti-Semitism against us, but there are no merits to those claims. The first president of the Bloodstained Men, Jonathan Friedman, was Jewish,” he counters. “We totally support the freedom of the individual to choose his own religion and not to have a religion that he has not chosen carved permanently into his genitals.”

Catherine Franklin, Courtney Shin, and Danii Alchemy protest male circumcision.

Photo by Jess Swanson

While the men in white are at the center of the protest, three women have joined them on the 13-day tour. Bloodstained Men secretary Catherine Franklin has even donned her own version of the getup for Friday afternoon, including a white skirt with a red stain at the crotch. (Anyone is welcome to wear the bloodstained suits, Atkinson explains, including women and intact men.)

“It’s like Americans scream, ‘Female genital mutilation is wrong!’ but then you don’t even think twice about male circumcision,” Franklin says. “It’s not just men who are speaking out. Women are upset about this, too.”

One female participant, who goes by Danii Alchemy, identifies as a “regret mother,” having witnessed her five-week-old son’s procedure.

“I was like, ‘If I can’t go back there and be present, then you’re not taking my son.’ So they agreed and we went back there. As soon as they started cutting into him, I immediately went into shock and knew that I fucked up,” she says. “I’ve been an intactivist ever since.”

Another woman, Courtney Shin, lost her voice from shouting at the earlier protests. Her husband was traumatized during his circumcision procedure when he was 4 years old. When their son was born, they did not circumcise him.

“It’s hard for my husband to talk about, but he still has a lot of sensitivity issues and a lot of emotional issues,” Shin whispers. “I have shown my son photos and explained this is what they do to baby boys but not you because we protected you.”

Antonio Moreno Ochoa is grateful he wasn’t circumcised.

Photo by Jess Swanson

As the protest comes to a close and the intactivists gather up their signs, banners, and pamphlets, an elderly man who says he’s visiting from Mexico City approaches the group with a grin and gives them a thumbs-up.

“I’m 70,” says Antonio Moreno Ochoa, adding that he’s uncircumcised and proud. “And this thing works!”