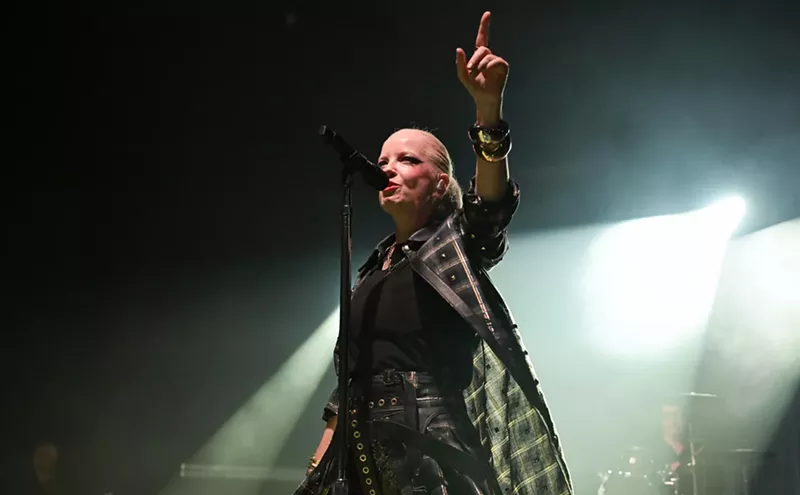

Why is Janice Turner grinning so widely? It's just after 7 p.m., 10 days before Christmas 2007, and she's backstage at the Y-100 Jingle Ball show at the BankAtlantic Center. There's a bunch of performances due to kick off in about a half-hour, but right now, folks are squeezed into the media room and there's not a whole lot happening — except Turner, with a smile that could power all the lights in Times Square.

Turner is making noise: dropping her cell phone, giving loud hugs, and generally upstaging Perez Hilton, the flamboyant gossip queen, which is no mean feat. And then, just as you're thinking no one could possibly look happier than Turner, you realize she's actually got the second-biggest smile in the room. The first is plastered on her son, who just spotted her, overnight reggae-pop star Sean Kingston.

Until his mom showed up, Kingston had been patiently answering questions from Hilton — the same Perez Hilton who makes a living trashing celebrities, not least Kingston. In fact, on his blog, Hilton had just been beating up Kingston, joined by readers who post hundreds of comments along the same lines: about how bad the then-17-year-old Kingston sucks, how fat he is, etc. — catty, spiteful, envious humor at its Hollywood finest, which is to say cruelest. Of course, this doesn't stop Hilton, chubby himself, from fawning over Kingston in person, a hypocrisy even more typical of Hollywood than the humor.

Kingston seems to notice or care about exactly none of it. He answers Hilton's questions about teen stardom the same way he's answered the same questions a hundred times already — pleasantly — until he suddenly cuts Hilton off midsentence, standing up and joyously hugging his mom and dragging her in front of the cameras for her cameo, essentially burying Hilton's bitchy little moment. Then he leads his mom to his dressing room, already filled with his sister, cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends, all awaiting face time with the big youth.

Some of these folks Kingston hasn't seen since his pop-star odyssey began two years ago. He's the youngest one in the room, with his neck and one wrist wrapped in diamonds, the hip-hop sign he's made it. He's also rocking a T-shirt, baggy jeans, Nikes, and a hoodie, an ensemble assembled by his personal stylist. Kingston, who signs his checks Kisean Anderson, is triumphant and seemingly not nervous, even though in less than an hour, he'll give his first big show in his native South Florida since his song "Beautiful Girls" took over radio, MTV, MySpace, iTunes, and the blogosphere.

Propelled by a mix of doo-wop, hip-hop, and urban pop, with a big nod to Ben E. King's 1961 hit "Stand by Me," Kingston's hit, his first, took him from zero to hero in three weeks flat, giving him the number one song on Billboard magazine's Hot 100 chart for four straight weeks, plus the top-selling ringtone in the country for five weeks. His "Beautiful Girls" sold 260,000 copies in its first week, the second-best debut in online history (just behind Rihanna's "Umbrella"). The song not only has cast his fame wide and fast, but also seems to have tamed critics from the New York Times to Rolling Stone, from Vibe to the Washington Post. His initial success has been downright tidal.

Still, tonight will mark the first time his mother has seen him perform before a large audience. While Kingston has traveled the world working hard, Turner, age 45, cooled her heels in a federal prison for more than two years for tax evasion and bank fraud. She was released in October. Now she's on parole, living in Sunrise.

Earlier in the evening, as he sat in the back of a van en route to the BankAtlantic Center, Kingston was asked what it meant to him for his mom to see him perform at this level, and he appeared to have trouble gathering his thoughts. "I'm just excited and ready to go" was the best the young man could muster, even as his forehead creased with stress.

There seemed to be no limit to the number of tickets his mom needed for this show — for the aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends who were also seeing Kingston for the first time in the flush of his stardom, after he went from the baby to the biggest breadwinner in their gene pool.

At times, it seems like a lot for a 17-year-old to carry. Kingston clearly would like to hang with his family today, for example, but he's also at work and more focused on his job — being a pop star — than his friends and family members probably realize. He's torn, and when he's whisked from his dressing room for a meet-and-greet with fans followed by a 10-minute interview with Entertainment Tonight, he actually sighs with relief. Bouncing from room to room for fans and cameras is what he already knows and loves.

Saying Sean Kingston is focused on his music doesn't quite do it. He's driven. He wants his piece of the big American prize; the only difference between him and a lot of other kids is that he actually has figured out, at a younger age than most, how to get it. He's been determined and self-confident as he turned himself from a young man with a pipe dream into a man-child who for Christmas proudly bought his mom a Bentley Continental GT, a $175,000 car, and had enough left over to buy her a house. It's the kind of rags-to-riches story that runs through so many songs in hip-hop and reggae, the two urban genres he combines.

Some of his critics say he's fakin' Jamaican, but the South Florida native was shuttled back and forth to Jamaica as a child and is proud of that island heritage. He was born at Broward General Hospital on February 3, 1990, and spent the first three years of his life bouncing around Broward County. Turner was a single, immigrant mother of three who ran her own businesses and worked other jobs. She didn't always have a lot of help, but her children were fed.

Sean is the youngest of the three. She says she's not surprised by his success. Music was in his blood, she says; her father was Jack Ruby, a producer for Bob Marley and Burning Spear and for years a hitmaker in Jamaica who also had a small role in the 1978 reggae film Rockers. "We're a very blessed family," Turner says by phone a few days after the BankAtlantic Center show. "We're not just stars because of Sean. We were born stars." Famous musicians were always around her house growing up and as an adult, she says, and she was a friend of reggae star Buju Banton, whose music influenced Kingston as a youth.

Even as a toddler, Kingston had a fascination with singing that initially seemed a bit odd, she says.

"He would always sing Whitney Houston's 'I Will Always Love You' until the veins popped up in his neck, back when he was three years old. I used to think, What's wrong with this little boy? — but he was serious. When he started going to school, he would just write lyrics in his notebook — not math or English, lyrics! I had to go to school every day. They said he was disrupting class, rapping all the time, getting suspended from school ... but it makes sense now because this was in him the whole time."

So was a rebellious attitude. As a child, Kingston frequently got into trouble at school, so much so that his mother moved the whole family to Jamaica when he was five, hoping it would bring the youngster some discipline. He remembers fondly the initial four years he spent there, living in Kingston, which would give him his stage name. "Those were the years when I really started singing for real," he says. "I started just singing in church and around the house every day. My sister was behind me telling me to keep it up and that I didn't sound bad, so I never stopped."

In an initial interview, he feigns having spent time around his famous producer grandfather, but that would have been impossible because Ruby (real name: Lawrence Lindo) died a year before Kingston was born.

By the time Turner's family moved to Miami in 1999, Kingston had developed a fondness not only for rapping but also for some of its negative attributes. He fought constantly, got tossed out of school, and worked his mother's last nerve until Turner sent him to a boot camp in Orlando for five weeks. "He begged me: 'Mom, pleasssse don't make me go,'" she says.

"I hated it at first," Kingston says, laughing. "But it made me a better person. I was doing drills, running five miles a day, waking up everyday at 5 a.m.... It was hard! But it was good for me. When I got out of boot camp, I wasn't fighting no more and getting into all that trouble."

Kingston returned from boot camp fixated on music, although he still got into plenty of trouble. His mother sent him back to Jamaica, by himself this time, to stay with relatives in Ocho Rios, where the bulk of his clan resides, hoping it would soften his desire to constantly show off and be the center of attention. His craving for attention only grew stronger, however. Family members noticed the only thing that seemed to temper his rambunctious attitude was music.

Recognizing the chance she had at keeping her son focused on something positive after he returned to Miami the next year, Turner made the greatest investment of her life.

"I bought him a little personal studio when Sean was about 11," she says. "He was still rapping back then, and he had all these silly different names — Bulletproof, Franchise, Lil Money. I said, 'You can't be Lil Money; you gotta be Big Money.'

"He's always had a love for music, and I knew he would be like this. I just didn't know it would happen this soon."

That the kid was a ham is apparently putting it mildly. According to Kathy Harris, principal at Congress Middle School in Boynton Beach, Kingston had a knack for stealing the spotlight. "Whenever there was somebody rapping in the lunchroom or after school, [he] would always jump in the middle of it," Harris says.

He was also expelled from almost every school he attended in the tricounty area. He seemed to be grappling with an internal battle: either remaining disciplined or constantly giving the finger to conformity. "Now that he's an entertainer, I can understand it a bit more, but back then, it was rough," Turner laments. "He got kicked out of Bair Middle in Sunrise, Christa McAuliffe in Boynton Beach. He couldn't even go to school in Miami he was so bad.... The list just goes on and on. Then he went to Delray Full Service, which was a school for bad kids, and he got kicked out of there.

"When he does listen, he learns. His grades weren't bad, but he made hell for the teachers."

Back at the BankAtlantic Center, as the Y-100 Jingle Ball concert gets under way, Kingston and his inner circle are finally finding time to act their age. After shaking off all the loved ones and hangers-on, he's left with his "interior crew," consisting of 17-year-old Baltimore rapper Young Leek, 18-year-old longtime friend Hype King, 23-year-old singjay Nathan "Mirror" Salmon, and his 23-year-old DJ, Kelo, all of whom are his friends and employees.

Aside from having a record deal as an artist on Jonathan J.R. Rotem's Beluga Heights label and a contract with Epic Records, Kingston started his own record label, Time Is Money — his attempt at being a player, coach, and owner at the same time.

Now that the grown folks aren't around — save Kingston's bodyguard — the teenage crew is dancing and laughing as Miami rapper Flo Rida and his Carol City Cartel are onstage. Flo Rida is opening the show, and his hit "Low" has an audience of predominantly white kids dropping down and gyrating like they're in a nightclub. At one moment, Flo Rida takes off his shirt, revealing rock-hard abs and a physique that looks like it was sculpted in prison. The women in the audience swoon, but with his pants hanging off his ass, his underwear showing, and his shirt off, he looks juvenile. Several artists backstage are watching the performance on television. With emo-rock group Plain White T's behind him and punk-pop outfit Good Charlotte off to his left, the businessman in Kingston surfaces. "Man, you don't get no sponsors looking like that," Kingston says. "I like Flo Rida, but that look is kinda tacky."

Soon, Rick Ross is on the microphone, and his thuggy-bear voice has all the 305 hip-hop lovers cheering and most of the younger MTV fans in the building looking perplexed.

Kingston doesn't have this problem when he performs, because his style is part ragga, part Nickelodeon, yet mature enough to make grown folks of any ethnicity want to dance. It's not easy to blend hip-hop and reggae without it feeling forced or gimmicky at the pop level, but Kingston's sound seems to be second-nature. It's a good deal of what makes him so marketable and why, as a debut artist after only eight months, his album is approaching gold status (which is admirable in this down era for the music industry). His ringtone sales are already platinum.

When it's Kingston's time to perform, all four members of his stage crew plus his road manager, Steve Lobel, gather for a brief prayer and then get to work. DJ Kelo cues up the music, and Kingston runs onstage in front of 15,000 screaming South Floridians and starts singing his second hit single, "Me Love," which is full of Caribbean flair and pop-crossover appeal. As far as the eye can see, the crowd mouths every word of it.

Despite the fact that it's an arena show, the sound is next to perfect, and Kingston's vibrancy and energy are infectious. The crowd of mostly tweens and teens is responding twice as loud as it did for previous performers. Next, Kingston jumps into "Dry Your Eyes," a song he wrote for Turner while she was incarcerated. He tells the crowd his mother is in the building and dedicates the track to her. Soon the chorus starts, and Kingston is singing:

Mommy, just dry your eyes; mommy, don't you cry,

I know we've been through hard times and the struggles,

And I just wanna tell you I love you ...

I got a little money, feelin' kinda blue

'Cause it's looking like you doing 10 to 20 ...

Some day I'm gonna buy you Miami,

So when I win my Grammy

You coming, 'cause I do this for my family.

Turner stands to the left of the stage, crying, as thousands of fans help him sing the song. He's bouncing all over, crooning with raw emotion. It's a powerful moment, marred only by the fact that the sweatshirt his stylist picked for him is too short.

Kingston spends his entire 20-minute set with his underwear showing.

After the performance, everyone in his family seems elated to have finally seen for themselves what all the fuss is about. When Kingston sang his signature "Beautiful Girls" just minutes earlier, the house lights were up, the crowd was on its feet, and the teenager looked like a seasoned pro.

Back in the dressing room, compliments are coming in droves. Kingston is shifting in and out of patois, depending on whom he's talking to, and laughing with friends. As he sits, he takes off a sparkling chain and hands it to a family member for safekeeping. It's a huge, 64-carat, multicolored diamond pendant in the shape of a Crayola crayon set. Two weeks earlier, he performed on Live with Regis and Kelly. After Regis Philbin asked him in a joking fashion how much his necklace cost, Kingston, showing his age, shouted, "$150,000."

When it's time for Kingston to greet his fans again, to sign CDs at a merchandise table, it's difficult not to notice that every moment of his time is accounted for by someone from Epic Records. He dons his massive chain and turns to head out the door, but apparently he's not moving fast enough for a few label reps. "Sean, come on!" someone yells, and without pausing, he retorts, "I'm coming, shit!" It's the first profanity he's uttered all day.

From the moment Kingston steps off the elevator for the CD signing, flanked by security, teenage girls scream his name, swept up in hysteria worthy of the Beatles circa 1965. His handlers rush him to a table as fans try to reach him, touch him, grab him: "I love you, Sean!" "Sean, I love you!"

Kingston makes sure his mother is seated right beside him as he spends the next 15 minutes writing his name. Girls in line snap his picture. The bolder ones flirt.

One girl, about 13, looks at Turner. "Are you Sean's mom?" she asks.

"Yes," Turner says, smiling.

"I love you for making him," another fan says. "Good egg!"

As Turner laughs, a fan is mouthing, "I love you, Sean, I love you."

For Kingston, this is life six nights a week. For Turner, this is unbelievable.

At six-foot-three and at least 260 pounds, with mahogany-dark skin, Sean Kingston looks more like late rapper Notorious B.I.G. than any prefab American teen idol. Kingston also shares some of Biggie Smalls's charisma, Jamaican heritage, and quick, lyrical wit. Now he's in the running to portray Smalls in a planned Hollywood biopic, along with Compton rapper Guerilla Black. Kingston, who has read for the part, says he's honored to be considered. Before he got noticed for his Caribbean crooning, rappers like Biggie and Jay-Z were big influences.

"In the early days, he was a serious freestyler," says friend Raheem "Hype King" Robinson. "He loved to just rap, rap, rap. He wasn't into the reggae chanting or the singing he's doing now. It was more Jay-Z-type, the Biggie or Nas feel. He could rap about your shoes or girls or whatever you told him to, right on the spot.... It was crazy to see a little boy doing that. Even back then, everyone knew he would be a star.... It was like, damn, how old is this dude?"

At the time, he was 12.

Robinson, who frequently works and travels with Kingston, was his childhood buddy. They met in Miami at Bayfront Park, at a reggae festival, and quickly bonded through their love of music. They began performing as a duo, with Robinson making beats in his dad's home studio and Kingston rapping over them. "We'd be at talent shows around the neighborhood," Robinson says. "The USA Flea Market on 79th Street, the SeaEscape cruises. We performed at concerts together in parks around North Miami Beach, block parties. It was all small stuff, but it was a start."

"By the time I was 13, I used to do whatever little promotions I could," Kingston says. "I'd go to the barbershop, and if it would say there was gonna be a talent show here or there, I'd just call up and register myself. The highest I ever got was second place. I thought that was pretty dope."

Kingston began making demos when he was at Congress Middle School. He'd sell them to other students, while Robinson pushed his music late at night on South Beach.

Around this time, little Sean chanced upon hip-hop producer Lil John outside a Miami nightclub. "He saw Lil Jon and walked right up to him and gave him his demo, all excited," Turner recalls during an interview at her new Sunrise home. "Lil Jon shook his hand and said he'd listen to it. Then, when Kisean turned his back, he threw it right on the ground. He thought it was funny. But Kisean saw him.... He came home so upset, like, 'Ma, I'm gon' be better than Lil Jon one day.'

"He was embarrassed, but things like that keep you going."

Kingston was honing his skills, but few people were paying him much attention. He probably seemed like a big kid with big talk. And then, one day in 2005, MySpace changed everything.

Kingston posted his first songs there when he was 14. He e-mailed every producer he could find online — Dr. Dre, Swizz Beatz, Polow Da Don — begging them to listen. None replied. Then he hit up Jonathan J.R. Rotem. In Los Angeles, the South African-born Rotem is known as a superproducer who's worked with A-list artists such as Rihanna, 50 Cent, and even Britney Spears, with whom he was briefly rumored to be romantically involved.

"I basically hit him up eight times a day for, like, three weeks and was like, 'Listen to my music, listen to my music,'" Kingston recalls. "I wasn't taking no for an answer....

"When J.R. finally listened to my music, he was ready to work. He gave me his number. I called him, we chopped it up, and he flew me out to L.A."

Rotem remembers it a bit differently. "I don't actually manage my own MySpace," he says by phone from California. "It was actually my younger brother Tommy that was doing it. Tommy was the one going back and forth working with him and sending him tracks and giving him a chance to show what he's got. I'm in the studio working with the who's who of the music industry. I don't have time to do MySpace. It takes a lot for someone to be able to make me shift my focus from working with established artists to helping a developing artist ... but Sean had it."

At the time, Rotem was launching his Beluga Heights label and seeking artists to sign. "We weren't looking for anything specific," he says. "It just needed to be something that was very, very different. In Sean's case, he was young, had amazing presence, there was a Jamaican influence ... he was just the essence of raw talent."

Rotem's success depends in part on his being a tastemaker, someone who can anticipate or even create trends. Pop music with Caribbean flair is all over the charts right now, thanks to the success of Kingston, Rihanna, Kat De Luna, and others, but its appeal wasn't as obvious three years ago, when producers like Rotem bet on it.

Kingston thought he was on the verge of hip-hop stardom. "He was concentrating more on rapping when we first met him," Rotem says, "but he was also singing his own hooks. We didn't just want a rapper that could spit 16 bars but someone who could write his own hooks, had melodic sensibility, crossover appeal, and with the Jamaican vibe. We knew Sean was the one."

Kingston was 15 years old. He got on a plane to L.A. Just a few months before, he'd been briefly homeless, sleeping in cars or on any couch he could find among friends in Miami, unsure where his next meal would come from. Federal agents had kept Turner under surveillance for some time, culminating in her arrest. Kingston's sister Kanema Morris was charged for conspiracy in connection with her mother's crimes. Kingston was too young to have had full knowledge of his mother's criminal activities, Turner says, but it was still a pivotal time for him.

Turner spent two and a half years in a low-security federal prison in Tallahassee, having been sent away just before Kingston's 15th birthday. "We lost everything," she says. "We lost our home, my cars, businesses ... the federal government took everything. Sean went to stay with family members, but he was so unruly that he left and went off on his own."

It was hard, Kingston says. "I was angry at the whole situation, and it was just a crazy time.... On one hand, it made me more focused, but it also felt like everything was falling apart."

Meanwhile, Kingston's sister Kanema, who was originally sentenced to probation, was cited for failing to answer her phone while she was under court-ordered monitoring and was jailed for four months in a low-security federal prison in Tallahassee.

By the time Rotem's organization was e-mailing him beats to work with, Kingston knew this was his chance to save his family, maybe the only one he'd get. He already had an older brother, Kurt Morris, on the West Coast, taking classes in Los Angeles. Relocating there made sense. And there was Rotem, who became a mentor.

Rotem recalls Kingston improved quickly once they started working together in a studio. "He was singing more on pitch, working on timber, and writing songs a lot faster.... When you're that young, you learn a lot quicker. He's real quick in the studio. He knows what kind of sound to go for."

In early 2007, Epic Records took an interest in Rotem's protégé, signing Kingston to a joint contract with Rotem and advancing the youngster enough money that he felt like a star for the first time. Kingston was 16.

Then "Beautiful Girls" began to get radio play, starting with Los Angeles station Power 106, and it didn't stop.

"I never knew it could happen so fast," Kingston says now. "It was amazing to me how big that song got."

Epic saw its opening and pushed to quickly get an album's worth of material from Kingston. Rotem had a month to help him do it.

"The single was taking off so quick, like way quicker than we expected, and we had to play catchup," Rotem says. "Every day we were making music together from afternoon until morning. We changed songs, verses, and hooks."

Listening to Kingston's self-titled debut album is like a walk through the mind of a 17-year-old with a lot to prove. What makes it stand out, however, is Kingston's fluidity, the way, with Rotem's help, he moves smoothly in and out of genres, creating an overall stew of reggae, pop, hip-hop, and doo-wop that remains crisp enough to appeal to 7-year-olds and 27-year-olds alike.

Kingston writes all the lyrics and keeps them clean. There's no profanity, no bragging about girls he's bedded, no attempt to portray gritty street life. "People don't want to hear a kid cursing," he says. "It's unnecessary. And that's not the kind of entertainer I want to be."

The second single off the album, "Me Love," has a patois chorus, poppy production, and an energetic, feel-good appeal that outstrips others' efforts at making reggae-crossover hits. This isn't Sean Paul or Shaggy. It's more like it's custom-made for the judges of the Teen Choice Awards ("Beautiful Girls" snagged two, for Best R&B Track and Best Summer Track). The flipside is that this kind of thing can get old fast. The "suicidal, suicidal" refrain from "Beautiful Girls" might sound different and even cool once, but it can also become annoyingly insipid with repeated play, just as Kingston can leave hipsters complaining he's too damn sweet.

"A lot of kids look up to Sean Kingston," Kingston says. "To me, that feels like an honor. I don't feel like a role model yet ... almost."

Kingston says he's sleeping less than ever these days and "flying more than a pilot." He's already appeared as a guest on MTV's The Hills, which he hopes is just his first acting gig. Still 17, he could tick off Japan, London, and Australia as his favorite locales. But when it came time to plan his 18th-birthday bash, he chose Ocho Rios, in Jamaica, where MTV would record the celebration and foot the bill.

Driving into Ocho Rios — "Ochi" to the locals — from Montego Bay on a Friday evening is tricky. You approach the city on a long, winding road crowded with shantytowns and jerk chicken huts that periodically fall away to reveal sublime tropical landscapes. The view is as poverty-stricken to your right as it is scenic on the left. There are traffic laws, but no one seems to follow them. Accidents abound. You hang on for dear life, and as you do, you notice the pink, yellow, and green posters whizzing by, taped to telephone poles, that read "Sean Kingston."

People in Jamaica love him, says his mom, who could not attend his birthday party because of parole restrictions. But he played a show here Christmas Day and flopped, at least one person says. "Him lose his culture," a cabdriver says as he whizzes through traffic. "People aren't sure if he can really do a stage show 'cause he only has three hits. Jamaicans want to see a lot of hits, like a Beenie [Man] or a Movado.... He's not there yet."

Indeed, Kingston has just one album so far. But when a local woman in her early twenties mentions his name that evening, all the other women around her begin to giggle and talk about how cute he is. "He doesn't need to lose a pound for me," one says. "Me love his big size and sexy voice," and she trails off singing the chorus to "Beautiful Girls."

His birthday party the next night is the talk of Ochi. There are rumors that Movado, Munga, Shaggy, and Beenie Man will come. (In fact only Shaggy showed up.) Tickets are going for the equivalent of $60. And someone's making a killing: The party is not even open to the public.

Kingston spends the day with friends and family. Everywhere he goes, a crowd gathers. People call his name and whip out camera phones. Traffic slows. When he visits his grandfather's famous studio, the streets are blocked off. He stops to eat fried chicken and is flanked by photographers from the local paper.

By nightfall, everything is ready for him at the Sunset Jamaica Grande Resort. Dancers and DJs entertain the crowd. Dressed in dark jeans, a white tee, and a white sport coat, Kingston makes his entrance to the screams of 200 friends and family members. A birthday greeting from his mom plays on a big screen: She says she has a Bentley Continental GT waiting at home for him, just like the one he got her. Of course, she seems to have bought it with his own money.

Kingston spends much of his time at the party dancing, posing for pictures with cute girls, toasting on the mike, and just clowning around. At midnight, he disappears for several hours, out of view of the cameras. Rumors circulate of an afterparty, the real party, where MTV won't be filming.

Around 3:30 a.m., the birthday boy reappears at Ocean's Eleven, a nightclub where thick ganja smoke wafts through the air and girls wearing next to nothing grind on men. Outside, the parking lot is packed with people burning spliffs and grilling jerk chicken. They're Ochi's rudeboys and dancehall queens, a much rougher element, from the looks of them, than anyone in the United States associates with Sean Kingston. Yet he seems at home milling through this crowd.

Inside, Black Chiney's newest selector, Dinero, is in the DJ booth. Mirror, one of the most talented artists on Time Is Money, is on a mike putting out a few of his dancehall bangers as dancers from different crews compete. Dinero, who lives in Coral Springs, keeps the crowd amped with "bumbaclaat" this and "bloodclaat" that, leading the club's angry-looking owner to tell him to keep it clean. So Dinero picks up the mike again and says, "All right, all right, no more bloodclaat swearwords, people. Watch ya bloodclaat language!" This has the crowd in stitches.

Just before 5 a.m., Kingston makes his way back outside, with most of the party following in his footsteps. They all still want a piece of him, and no one knows when or if he'll be back this way. Some want photos, some try to hand him CDs, some attempt to get him to agree to make music with them at some later date. A few look thuggish and jealous, which is understandable as their women gravitate toward him. Kingston has to be careful making his next move, but as he breaks away from a few ladies, he says, "This whole thing is like a dream come true."