Monkeys and other nonhuman test subjects have been an extremely valuable research component in helping the medical community better understand COVID, which has so far killed 290,000 people in the U.S. and more than 19,000 in Florida. In two peer-reviewed studies published this spring in Science magazine, researchers who infected groups of rhesus macaque monkeys with the coronavirus found that primates were capable of developing protective immunity against the disease. That development helped pave the way for the vaccines that could start to put an end to the pandemic.

At least five entities in Florida, including one in Miami-Dade, import or breed monkeys for research and testing purposes. In 2017, at least 1,729 monkeys were used in lab settings in Florida, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Now, a skyrocketing demand for laboratory subjects has led to a dire shortage of test monkeys, according to the National Primate Research Centers, a network that provides support for researchers who use monkeys in biomedical research.

"Nonhuman primates are a critical part of the development process for any human healthcare application," says Dr. Joyce Cohen, a veterinarian who serves as the group's associate director for animal resources. "So for vaccines, that's really essential, because we are extremely closely related to non-human primates, and their responses [are] most similar to what a human response would be."

Although monkeys comprise only about one-half of one percent of the animals used in U.S. research, they are often part of the last stages in development before testing can advance to human trials.

In the case of COVID vaccine research, test monkeys have been infected with the virus in controlled settings where researchers have monitored how the animals' immune systems — which closely resemble a human's — respond to various treatments.

The practice is not without controversy.

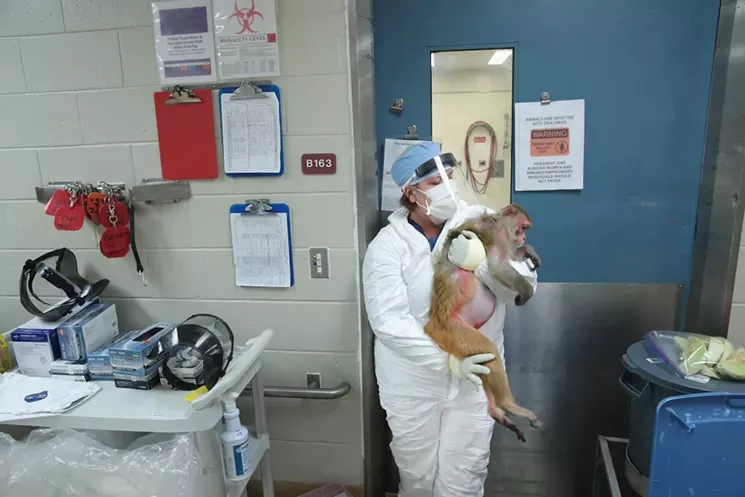

A researcher carries a monkey infected with the Zika virus in 2016. Similar research has helped develop the COVID-19 vaccine.

Cohen says there is little cause for concern. She points to what she characterizes as "stringent" regulations governing the welfare of the monkeys.

"The way in which we care for the animals is regulated, down to the size of the enclosure that they're in to the number of times a day we offer them food, as well as, of course, pain management and anything else," she explains.

Nevertheless, animal rights groups like the ARFF say regardless of what kind of research is being done, testing on animals is inhumane. Earlier this year, the organization attempted to intervene when it discovered monkeys were being shipped to Florida to become test subjects.

Nick Atwood, a spokesperson with the ARFF, tells New Times the advocacy group learned over the spring that an airline, Skybus Jet Cargo, had been contracted to transport monkeys from the East African island nation of Mauritius to Miami for lab research related to COVID.

The ARFF joined forces with other animal-rights groups and pressured the airline to pull out from what Atwood says was a nearly half-million-dollar deal. After some back and forth and multiple attempts to reschedule the flight of the monkeys, Skybus walked away.

The ordeal was chronicled in a civil suit filed in September by a third-party logistics group orchestrating the transfer, International Logistics Support LLC. (The Miami Herald first reported the existence of the civil suit.)

According to court filings, Skybus cited COVID-related concerns when it first informed the logistics group it had to delay the trip. But after at least two attempts at rescheduling, Skybus reversed course and backed out of the agreement. Despite the apparent COVID issues, Atwood also credits the efforts of animal-rights activists.

Atwood says it's his understanding that roughly 1,200 monkeys were originally part of the deal. New Times could not independently verify the number of primates.

"We learned that Skybus actually did not go forward with the [original] shipment, so our campaign was somewhat successful," Atwood says.

Atwood says "somewhat" because, according to court documents, the logistics group ultimately secured another cargo airline to transport a smaller number of monkeys, though Atwood is not sure how many and the documents do not specify a number.

Atwood believes the monkeys may have been en route to Worldwide Primates, a Miami-based company that supplies nonhuman primates to research labs, adding that the group has been awarded at least $5 million in federal contracts this year to sell monkeys specifically for COVID research. Worldwide Primates did not respond to emails from New Times seeking comment.

Although it's unclear how many monkeys were transported to the U.S. or where they were taken, Atwood says he and his colleagues did their part to ensure the bulk of the animals were steered clear of becoming lab subjects, their importance to vaccine development notwithstanding.

"We're opposed to the use of animals for experimentation and testing on moral grounds," he says. "We think animals have a fundamental right not to be harmed. We think a better way of finding that vaccine is through human clinical trials and other non-animal methods."

Scientists involved in vaccine development acknowledge that there are tradeoffs but contend that research requires certain risks and sacrifices. Paul Offit, a co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine who serves on the FDA's COVID vaccine advisory panel, said on a recent episode of the Radiolab podcast that vaccine research can take a toll not just on animal test subjects, but also on the humans who end up on the wrong side of the experiment.

"You're constructing an experiment where, by definition, you're not going to learn unless people suffer, are hospitalized, or die," he said. "That's the experiment you're conducting."

But, Offit said, that's how scientific advances are discovered: "There has never been a medical breakthrough in history that has not been associated with a price."