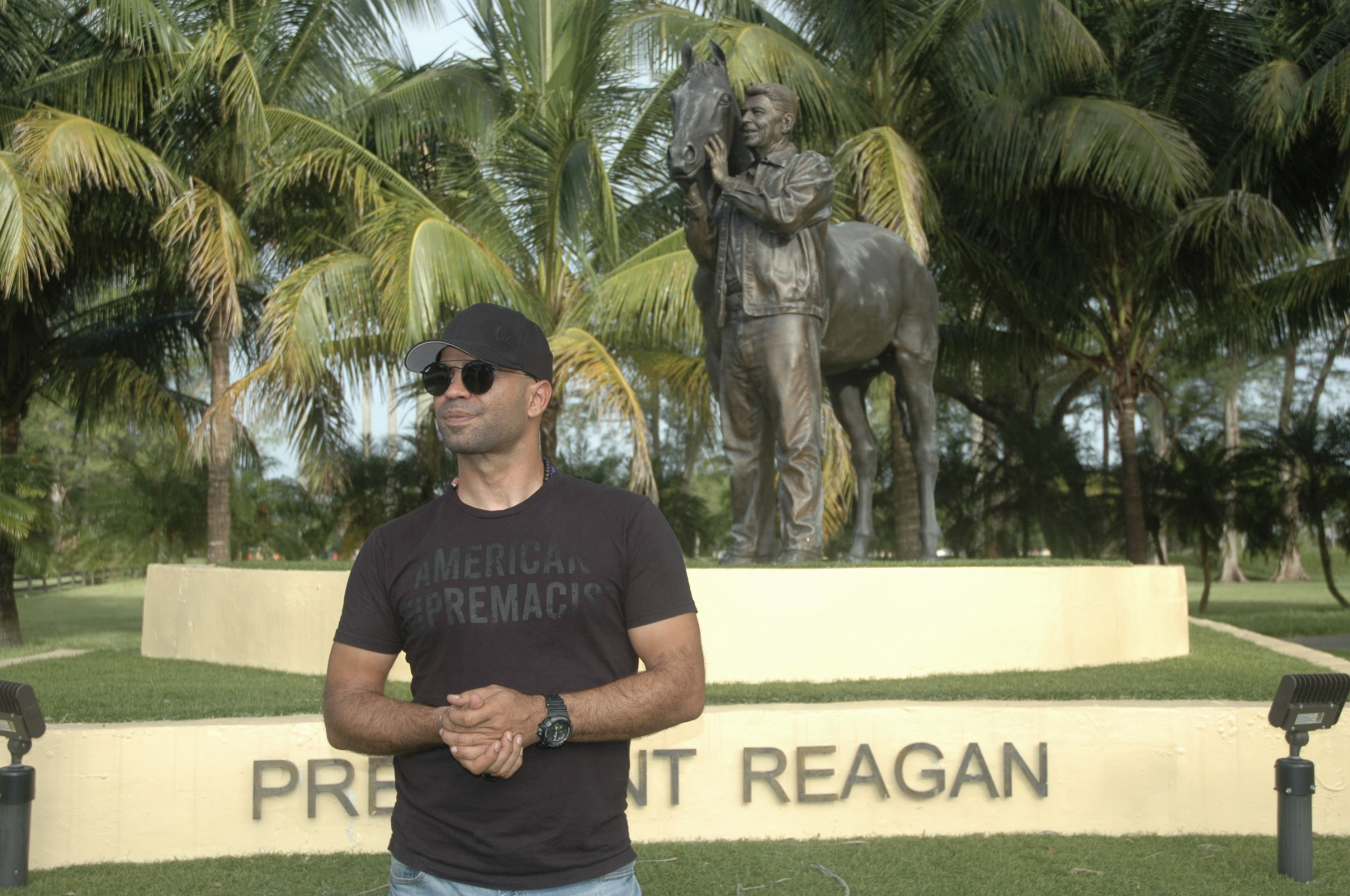

Photo courtesy of Enrique Tarrio/Photo by Michele Eve Sandberg

Audio By Carbonatix

Update published 1/22/2025 10:50 a.m.: After serving just 16 months of his 22-year sentence for seditious conspiracy and other charges, Tarrio was released from prison on January 21. This came after President Donald Trump pardoned him and more than 1,500 other January 6 defendants.

Tarrio had been serving the longest sentence of any January 6 defendant.

Update published 9/5/2023 6:10 p.m.: Enrique Tarrio has been sentenced to 22 years in prison for his role in orchestrating the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol. Read the latest on the seditious conspiracy case against Tarrio here.

The original story covering Tarrio’s rise as the Proud Boys’ captain and his 2021 sentencing for previous charges follows below.

I: Sentencing Party

Enrique Tarrio’s mother, warm and doting behind round-rimmed reading glasses, sets up a table with guava-and-cheese pastelitos and passes around small plastic cups of cafecito to members of her son’s inner circle of conservatives, mostly friends he’s made from political campaign work. On this sweltering day in late August, they’ve gathered at Tarrio’s air-conditioned recording studio, tucked away in a nondescript business center just east of Tropical Park, to support the 37-year-old Proud Boys chairman during his virtual sentencing proceedings. Two months ago, Tarrio had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of destruction of property and attempting to possess a high-capacity ammunition magazine in a pair of incidents dating back to December of 2020, when members of the Proud Boys burned a Black Lives Matter flag in Washington, D.C., and then when Tarrio returned to the nation’s capital a month later and was caught carrying firearm parts in his backpack.

“You’re making this look like a party,” Tarrio jokes to his mom. Dressed in blue jeans and a distressed Team Tarrio cap, Tarrio wears his signature black Ray-Bans indoors as well as out, explaining that a photophobia condition makes him sensitive to artificial light, causing headaches and anxiety. Indeed, short of candles and cake, it seems more like a family birthday celebration than a sentencing hearing, with Tarrio as the guest of honor.

Tarrio’s attorneys predict he’ll get probation. For now, everyone’s smiling and gabbing amid the Proud Boys and Trump 2020 banners and photos of Tarrio at pro-Trump boat parades and on newspaper front pages. This is where Tarrio runs his 1776.shop, a merchandise site where he prints T-shirts, offers custom engravings on coins and gun magazines, and hosts strategy meetings for various groups he declines to name. Racks are piled high with the right-wing tchotchkes and paraphernalia Tarrio designs and sells – from pen holders made of gun cylinders to pro-Trump stickers to Right Wing Death Squad patches. In the office’s attic space, several thousand dollars’ worth of Trump 2020 campaign material sits unused, unsold, and gathering dust. A statuette of Iron Man – one of Tarrio’s favorite superheroes – and a Funko Pop of Baby Yoda from The Mandalorian perch atop a cabinet filled with Proud Boy mementos.

At 2 p.m. Tarrio separates from the guests and steps into the soundproof room where he records episodes of the NBLE Podcast (available on Rumble, but not Spotify or Apple Podcasts), joined by his friend and “spiritual advisor” Souraya Faas, who has prepared a prayer for him to recite. They log into the court’s online video-conferencing site, where District of Columbia Superior Court Judge Harold L. Cushenberry, Jr., initially fumbles Tarrio’s charges, confusing the misdemeanor charges for felony ones and mistakenly stating that Tarrio was charged with two counts for possession of high-capacity magazines when there was only one count.

Then comes the sentence: 155 days – more than five months – followed by three years of probation. Tarrio must turn himself in at a Washington, D.C., jail in two weeks.

“Mr. Tarrio did not care,” Cushenberry declares. “That’s what I think. He cared about himself and self-promotion. He didn’t care about the laws of the District of Columbia.”

In the adjoining room, friends and family, who’d been following along on a small monitor rigged up for the proceedings, hear the sentence and begin to cry. Any sense of levity having vanished, everyone fumes, protesting to one another about the unfairness of it all: a blame game of liberal politics and conspiracies that Democrat operatives like Nancy Pelosi may have had a hand in.

Seated in his studio chair, Tarrio doesn’t so much as flinch.

“Here’s my statement: Just like Jeffrey Epstein, I’m not gonna kill myself in jail.”

After he logs off and calls his attorney to clarify the terms of the sentence, Tarrio walks out of the studio and speaks privately to his mother and sister in the kitchen. The women are in tears. Tarrio still seems unfazed, or perhaps in shock.

Deep down, he’s pissed off: His request to bring in a character witness to speak on his behalf – Christian activist Bevelyn Beatty, a Black woman who was accused of defacing a Black Lives Matter mural – was summarily denied. He is convinced he was selectively prosecuted because of his political beliefs and high-profile position with the Proud Boys. And the judge said his attempts to show remorse weren’t convincing or genuine, despite the fact that he apologized profusely in court and insists to this day he’s sorry for having destroyed someone’s private property – an action that, he admits, conflicts with his Libertarian beliefs.

And yet he emerges from the kitchen, enters the workspace where his dejected friends have gathered, and with a toothy grin quips, “Here’s my statement: Just like Jeffrey Epstein, I’m not gonna kill myself in jail.”

When his lawyer calls with legal advice, he asks for tips on saving gas while driving up to D.C. to turn himself in. (He’ll later concede that the jokes and smiles were for his mother and sister – they’d been through enough.)

By Labor Day, Enrique Tarrio will be behind bars, ending his three-year reign as Proud Boys leader – a period during which the right-wing organization catapulted from a politically incorrect men’s club to a widely recognized hate group that has violently clashed with antifa and Black Lives Matter protesters and rallied alongside professed white nationalists and extremists. Thrust into the national spotlight by then-President Donald Trump amid the 2020 election campaign, the group remains entangled in the postmortem of the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, during which several Proud Boys entered the building and interrupted the election certification of President Joe Biden. (Tarrio was an hour away in Baltimore at the time.)

Tarrio’s notoriety emboldened him to seek political office last election cycle and to consider another bid for local office in the near future. In that respect, the timing of his imprisonment could hardly be worse: The original Miami Proud Boys chapter Tarrio helped create has split over internal tensions about their leader, and some longtime members seek to distance themselves from an organization that has increasingly tipped toward violence.

To anyone raised in Miami, the rough outlines of Enrique “Henry” Tarrio’s biography might sound familiar: The son of Cuban immigrants who fled political persecution and set down roots on the streets of Flagami, he was brought up Catholic and with a good deal of right-leaning politics infused into family conversations. He dropped out of high school, having developed more interest in being his own boss than in furthering his education.

What will become of this Miami boy turned hate group leader turned jailbird? Will he run for office? Re-emerge to lead a new movement that rides the stubborn MAGA wave? Or will he be consigned to obscurity, a neo-fascist flash in the pan?

“Like I said before,” he says defiantly, “I’m not fuckin’ leavin’.”

Since becoming chairman in 2018, Tarrio has moved the Proud Boys in a decidedly political direction, and launched them into the national spotlight.

Photo by Michele Eve Sandberg

II: Becoming Proud

At first, Tarrio didn’t want to join the Proud Boys. He thought the name was too “gay.”

“It sounded like a gay pride thing,” he says, tapping ashes from a Marlboro Gold into a Liberal Tears mug. “It wasn’t rebellious, like ‘the Patriots’ or some shit.”

Tarrio was courted by a veteran Proud Boy at a May 2017 Miami mansion party for rightwing provocateur and internet troll Milo Yiannopoulos, toasting a pending lawsuit against Simon & Schuster over the cancellation of a book deal. Tarrio wasn’t present in any official capacity; he’d been asked to provide doorway security for the fancy bacchanal in his role as proprietor of Spie Security LLC, which provided consulting and security services. But that’s how he met Proud Boy Alex Gonzalez, future president of the Miami Proud Boys.

The two men took to one another quickly.

“He was Cuban, and I vibed with that, and he was a business owner,” Tarrio says. “We kind of just spoke all night.”

Over the week that followed, Tarrio rebuffed Gonzalez’s repeated attempts to induct him into what he called a fraternal “drinking club,” the kind of place where grown men could get away from their families and be themselves without fear of reprisal for political incorrectness.

Tarrio, 33 years old at the time, was already once-divorced (after a brief marriage in his early twenties) and was working at Spie Security when he wasn’t “shaking hands and kissing babies” on the campaign trail for Lorenzo Palomares, a Republican vying for the Florida Senate. After a few days of prodding, though, he relented. He was intrigued about the group and its founder, Gavin McInnes, the Canadian co-founder of Vice magazine who became an extreme far-right online commentator.

Gonzalez invited Tarrio to a Proud Boys meeting in Broward County, and when the event was canceled, Tarrio suggested moving it to his house in Flagami. (“I fucking hate driving to Broward,” Tarrio says.) He expected a large gathering; he’d cleared the driveway and fired up the barbecue. But only two men showed up.

Tarrio wasn’t deterred. He saw potential.

“Before me – and they hate it when I say this – they were the Gavin McInnes fan club,” Tarrio says. “We weren’t really political.”

From that initial meeting in May 2017, Tarrio rocketed through the ranks. Within his first year, he was being invited to the Breakers resort in Palm Beach for breakfast with former Trump strategist Steve Bannon and Sebastian Gorka, who at the time was a member of the president’s inner circle. They were meeting with McInnes to discuss upcoming elections.

In August of 2017, Tarrio and other Proud Boys were present at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The event, which was widely attended by white nationalists and hate groups, is best remembered for the death of Heather Heyer, a counterprotester who was killed when a participant rammed his car into a crowd.

A year later, in 2018, Tarrio rose to the station of so-called Zone Lead for the Proud Boys South Florida chapter and then cofounded the Vice City Proud Boys chapter in Miami.

Tarrio doesn’t operate on a dial but rather a light switch: When he gets into something, he gives it his undivided attention. He quickly embedded himself as a fixture with the national organization, organizing networking events and rallies for the Proud Boys in Florida and abroad.

“That guy eats, sleeps, and breathes Proud Boys – he’s 100 percent loyal,” says a former Vice City Proud Boy who asked that his name not be published. “When I was going through something with my kids, he would call me every day to see how I was doing.”

With his growing connections, Tarrio started to steer the group in a decidedly political direction.

“Before me – and they hate it when I say this – they were the Gavin McInnes fan club,” Tarrio says. “We weren’t really political.”

The Proud Boys continued making headlines. No longer for drinking beers together and going over the finer points of McInnes’ podcast, but for brawling with anti-fascists and Black Lives Matter protesters at rallies and counterprotests across the nation. Their hard-to-overlook ties to white supremacy earned them a “hate group” designation from the Southern Poverty Law Center in February of 2018.

Tarrio often japes about the designation, embracing his title as a hate group leader when talking to journalists.

In November of 2018, seven Proud Boys were arrested for a violent street fight in New York and the FBI designated the organization as an extremist group, like the far-right Oath Keepers. McInnes stepped down as leader, leaving a power vacuum. (The FBI would soon walk back the “extremist” designation, stating that it had been applied in error but that the Proud Boys indeed had ties to white nationalism – a claim both McInnes and Tarrio deny.)

Though Tarrio recognized an opportunity, he hesitated; he was already president of the local Vice City chapter. But he didn’t want the group’s then-attorney, Jason Lee “J.L.” Van Dyke, to take the reins, either.

“I saw J.L. as a problem,” Tarrio says now. “He was a very aggressive person, and I didn’t think he had it in him to lead this group.”

(Van Dyke would later be accused of trying to use members of the Proud Boys’ Arizona chapter to assist in a failed assassination plot against Thomas Christopher Retzlaff, whom Van Dyke had sued for defamation. Van Dyke denied he had any plan to harm Retzlaff and maintained there was no Proud Boys involvement in the alleged plot.)

When a chapter president suggested Tarrio run and circulated memes of him campaigning, he said, “Fuck it.”

The day after Thanksgiving, during an annual family vacation in the Florida Keys, he woke up to find he’d won in a unanimous vote.

Suddenly, an Afro-Cuban Miami boy was the leader of a nationally recognized hate group with reported ties to racist extremists.

Sitting in the recording studio of his 1776.shop office on August 23, Tarrio awaits the sentencing for his misdemeanor charges of destruction of property and attempting to possess high-capacity ammunition magazines.

Photo by Joshua Ceballos

III: Miami Roots

Sipping a colada at the ventanita of a small Cuban restaurant in Flagami, Tarrio looks wistfully toward West Flagler Street between drags of his Marlboro Gold. The sun glints off his black Ray-Bans.

He’s been preparing to go to jail for some time now. Though he’s always been active, traveling across the country for the Proud Boys or some other political objective, it’s as if the past four years have caught up to him all at once.

“I’m tired, man,” he sighs. “I need a break.”

After blowing kisses to the chatty ladies at the ventanita, Tarrio takes the short walk down a narrow residential street to a wide, singlestory corner house fringed by short, foxtail palms, with a large, tiled patio equipped with plastic lawn chairs. It looks more like a Cuban-American retirement home than the headquarters of the leader of a hate group.

This is the house where Tarrio grew up in the early ’90s and where he now lives with his grandfather. The middle-class residence is one part abuela’s cottage, one part bachelor pad. The refrigerator’s covered with Disney magnets, and an entertainment setup houses a wall-mounted monitor and an Xbox One gaming console. A full-length mirror in the living room doubles as a clandestine sliding door to Tarrio’s day room, where he lies in bed and watches television on a ceiling-mounted screen between stints of traveling.

The walls are decorated with photos of Tarrio’s father (also named Enrique), relatives, and Tarrio himself as a cheerful child and stoic teen. In one photo, a young Tarrio kneels and prays to a statue of San Lázaro.

In the dining room sits a boxy TV that’s older than Tarrio. This is where he’d listen as his family gathered around the table to share cafecitos and political opinions, most of them conservative. Essentially, it’s the place where young Enrique Tarrio was politicized.

As Tarrio tells the story, his granduncles refused to give up their farmland to Castro’s revolutionaries and were executed by Communists. His grandfather fled to South Florida with his family and Enrique Sr. in the 1960s.

“All my friends are second-generation Cubans, you know. So even if they’re apolitical, they’re right-wing and have conservative values.”

Tarrio’s father worked as an automobile mechanic. His mother worked in import and export logistics. They divorced in 1992 when he was 8 years old.

Tarrio’s mother, Zuny Duarte, came to the U.S. from Cuba, but she says she was never a very political person. It was her ex’s side that talked ideology, Duarte says. In fact, she doesn’t watch the news unless someone sends an article that mentions her son, and she had to be reminded when and where the January 6 insurrection took place.

She describes her son as a regular boy who rarely got into trouble. He was talkative in school. Spoiled, but never a brat. “He always liked to share his things,” Duarte says. “He would give away things that we gave him. He still shares everything.”

Many kids dream of what they want to be when they grow up. Not Tarrio. He didn’t want to be a dentist or a veterinarian. He didn’t belong to clubs or play organized sports. His mother says he’s been an avid gamer since she bought him a Nintendo console as a kid. To this day, Tarrio keeps Funko Pops and statues from popular game franchises like Halo and Gears of War around his home and office, and his recording studio looks like it could belong to a Twitch streamer.

“But he was always very social in school and always had the same friends,” she says.

Tarrio attended high school at a now-shuttered private institution in Sunset called Il Savior Academy, until dropping out during his 11th grade year. He and his friends would skateboard in the parking lot of the laundromat next door or venture out on small fishing boats on Blue Lagoon, just south of Miami International Airport. Often, they’d just circle around the long dining room table, absorbing the right-wing philosophy of their Cuban elders.

Many of those same friends are still with Tarrio to this day, and some have even joined him in the Proud Boys.

“All my friends are second-generation Cubans, you know. So even if they’re apolitical, they’re right-wing and have conservative values,” he explains.

Tarrio says he always wanted to own a business. Didn’t matter what kind. After dropping out, he dedicated himself to selling auto parts full-time. He had hair then: short, black, and neatly lined; his head has been hidden under a seemingly ever-present cap since he began going bald at 24.

His family calls him Henry, although his birth certificate says “Enrique.” The name stuck, and he used it in school and on his driver’s ed test. It’s listed on Spie Security filings with the state. Court documents from his string of legal cases often alternate between the two names.

In December 2012, Tarrio and two others in Miami were indicted on charges of misbranding medical devices and conspiracy to sell stolen goods in connection with a scheme involving diabetic test strips. According to court documents, Tarrio and his co-conspirators received stolen test strips and re-labeled them with false lot numbers and expiration dates before selling them across state lines, in violation of federal law. Tarrio was sentenced to ten months in a federal prison camp in Pensacola, followed by five months in a halfway house near Little Havana in Miami.

In 2014, while serving out his sentence at the Riverside House, Tarrio began commenting on 4Chan and Twitter about Gamergate, a harassment campaign against women in the gaming industry that led to greater focus on sexism and gender inequality in gaming. Tarrio didn’t see it that way and viewed the backlash as more “antimen” than “pro-women.”

Though the Little Havana house is listed under the name of his grandfather and roommate Rigoberto, Tarrio says he bought the property nearly a decade ago to keep it in the family when his grandfather had to sell it.

Tarrio employs his mother and sister at 1776.shop. But for the past few months, the family business hasn’t made a single sale. That’s because credit-card processors refuse to work with them, purportedly because the merchandise they sell is offensive and violates the companies’ terms of service. Tarrio believes it’s because he’s “persona non grata” owing to his Proud Boys affiliation. He says he has been supporting his family out of his own pocket while they look for other ways to make money. (Tarrio says he still has considerable savings from his days as a security contractor with Spie Security, which he’s dipping into to cover his family’s expenses.) While he’s in jail, Tarrio says, they’ll continue to run the shop and look for a new credit-card processor.

In his backyard, Tarrio keeps pigeons. Their cages lined with shit-stained posters from Ron DeSantis’ 2018 campaign for governor.

He says he seriously got into politics through his paternal aunt, Zaida Nuñez, who was a prolific campaigner for Republicans and brought young Tarrio along to help.

He’s tried to make the transition from organizer to politician before, but his 2020 bid to unseat Democrat Donna Shalala in Florida’s 27th Congressional district petered out because he couldn’t accept campaign donations owing to the ongoing issue with credit card processors.

That hasn’t stopped him from considering another shot at elected office. Only weeks before his sentencing, he said he was considering announcing his candidacy for a seat on a local city commission, or for another congressional seat. With all the media attention he’s received over the past several years, he’s certain he has the name recognition to win.

But for now, Tarrio is restless. He walks down the driveway, the same one where those first three Miami Proud Boys met in 2017, passing over a faded “P” and “B” from a banner he and his men spray-painted on the pavement.

Tarrio’s out of breath. He blames it on chain-smoking cigarettes, says he needs to quit.

The Proud Boys have clashed with Black Lives Matter protesters and anti-fascists in cities throughout the nation, often resorting to violence.

IV: Stand Back and Stand By

With Tarrio at the helm, the Proud Boys dominated national headlines: He and other members were removed from Facebook and Twitter in the fall of 2018 for violating policies against violent extremist groups. The Proud Boys held or attended events, including the Demand Free Speech rally in D.C. in July 2019, where they protested their social-media bans (and skirmished with counterprotesters); and the End Domestic Terrorism Rally: Better Red than Dead in Portland the following month, where they demanded that “antifa” be considered a terrorist organization. In the summer of 2020, as more than 15 million people joined the Black Lives Matter protests, members of the Proud Boys would brawl with anti-fascists and BLM supporters at demonstrations across the nation.

On September 29, 2020, Tarrio was reclining on his mother’s couch during a family barbecue, exhausted after returning from rallies in Portland. On TV, Trump and Joe Biden were squaring off in Cleveland, in the campaign’s first presidential debate. Tarrio was dozing off when Biden began talking about Portland, where Trump supporters and anti-fascist protesters had violently clashed after months of nonstop social-justice demonstrations. Tarrio cocked his head. When they started to talk about white supremacist groups, he sat up and inched closer to the TV. Then Biden mentioned the Proud Boys by name.

Fuck, fuck, fuck, what’s going on here? Tarrio thought.

Then came the clarion call from the commander-in-chief himself: “Proud Boys, stand back and stand by.”

Tarrio never did finish watching the debate. His phone blew up with messages from reporters as far away as Germany, Canada, Mexico, and Japan. A flood of new recruits were eager to join a group seemingly endorsed by President Trump.

“My life changed after that,” he says now. “Completely.”

On December 12, 2020, during a massive protest of President Biden’s election victory – which to this day Tarrio baselessly maintains was fraudulent – a raucous group of Proud Boys in Washington, D.C., stole a Black Lives Matter banner belonging to the historically Black Asbury United Methodist Church, and burned it. On his Parler account, Tarrio posted a photo of himself holding an unfired lighter on the day of the protest. Online and in interviews following the protest, Tarrio took credit for setting fire to the flag and publicly said he was proud of having done it.

A former Proud Boy who says he witnessed the burning tells New Times Tarrio didn’t actually burn the flag but took the fall so other members wouldn’t be charged with a hate crime. Tarrio declines to discuss the matter.

“I probably blame what happened on January 6 on me not being there. Maybe we would’ve stopped a lot of people from going through that first barrier and stopped the whole thing.”

Less than a month later, on January 4, Tarrio returned to D.C. to protest the certification of the election but was arrested for the flag burning before the protest began. He was charged with destruction of property and with carrying two high-capacity firearm magazines (a violation of D.C. law). The magazines were empty; Tarrio says he’d engraved them with the Proud Boys insignia at his shop and was delivering them to a client.

Tarrio made a deal and pled guilty to the charges, both of which are misdemeanors. When Tarrio was released on January 5, he was told not to return to Washington, D.C. So he drove north to Maryland to await his flight back to Miami two days later. He was in his Baltimore hotel room when members of the Proud Boys and scores of right-wing protesters stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6 to interrupt the certification of Biden’s victory in a riot that sent members of Congress running in fear and claimed the lives of five people. (Seven Proud Boys, including two from Florida, remain incarcerated for their roles in the insurrection.)

“I probably blame what happened on January 6 on me not being there,” Tarrio laments. “Maybe – it sounds crazy, but I think we would’ve stopped a lot of people from going through that first barrier and we may have stopped the whole thing from happening.”

Amid the chaotic news cycle that followed, Reuters published an exclusive by Aram Roston revealing that Tarrio had been a “prolific” informant for federal law enforcement, allegedly providing details that helped prosecute people in cases involving drugs, gambling, and human trafficking.

Tarrio says he agreed to assist federal law enforcement when he was indicted in 2012 for the diabetes test-strip scheme to reduce his own sentence and to keep his stepbrothers, who worked with him, out of jail. He says his cooperation consisted of supplying the names of “coyotes” whom he knew had smuggled migrant workers across the Mexican border into the U.S.

News of the chairman’s status as an informant sent fractures through the Proud Boys apparatus. Many members suspected he was still a government “rat.”

Earlier this summer, several members of Tarrio’s own Vice City chapter voted to disavow their founder, splitting the Miami branch into two factions: Vice City and Villain City. The latter is the chapter Tarrio now leads, along with several veteran Proud Boys, including Alex Gonzalez. A former Vice City Proud Boy tells New Times that he and other members splintered off to create their own organization, not because of Tarrio, but because too many “Nazis” and “gang members” had infiltrated the group following the insurrection.

Three days after Tarrio’s August 23 sentencing on the D.C. charges, seven U.S. Capitol Police officers filed suit against Tarrio, Trump, and members of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers for actions that led to the January 6 insurrection.

Speaking by phone the day after the lawsuit was announced, Tarrio says he’s become numb to everything that was happening. He calls the new lawsuit “frivolous.”

“I’ve got no faith in this fucking justice system,” he says. “How much more shit are they going to throw at me?”

The Proud Boys have begun increasing their political presence in Miami, showing up to Cuban solidarity demonstrations and school board protests.

Photo by Michele Eve Sandberg

V: Hard to Pin Down

In a narrow sense, Tarrio has a point.

At the sentencing hearing, Judge Cushenberry handed down two incorrect sentences and had to be set straight by federal prosecutors, creating an impression that he either had not read the case carefully or that he already had a punishment in mind for the Proud Boys leader.

On the other hand, it’s hard to muster sympathy for the leader of a group known to act as a gateway to extremist ideologies.

“They are information launderers,” CV Vitolo-Haddad, a University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher who analyzed the Proud Boys’ social networks, told New Times‘ Meg O’Connor in 2018. “They take much more extreme ideologies and launder them into the public eye under the guise of irony.”

It’s also a stretch to see one’s way through to feel for a group that engages in violence against protesters. And journalists.

Daniel Rivero, a reporter for Miami’s public radio and TV network WLRN, says that in August, at an anti-mask protest outside the Miami-Dade County Public Schools building, a man standing among a group of Proud Boys assaulted him when Rivero photographed the group.

“He started bumping me with his belly and said, ‘Take that off your fucking camera or I’m gonna bash your fucking head in,'” Rivero tells New Times.

“The Proud Boys may say they reject white supremacy, but they have consistently, over many years, teamed up with overt white supremacists.”

Though Tarrio says his group denounces racism, violence, and extremism, the Proud Boys always seem to be present where those beliefs and behaviors proliferate, and vice versa. Tarrio’s own online posts show clear signs of transphobia and a penchant for violence.

“The Proud Boys may say they reject white supremacy, but they have consistently, over many years, teamed up with overt white supremacists,” says Cassie Miller, a senior research analyst with the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The Proud Boys profess to believe in what they call “Western chauvinism,” which, as Miller explains it, boils down to putting societal control in the hands of men, especially white ones.

One on one, Tarrio is soft-spoken, seemingly tolerant, and at times funny. He’s a lot like many a Cuban-American cousin or high school friend. In that respect, one could easily mistake him for any other Miamian raised on the conservative rhetoric of el exilio.

Yet he’s a man of contradictions. He’s the leader of a self-labeled drinking club but he doesn’t drink, having been turned off by alcohol in his early twenties. He says he’s not religious, but he wears necklaces representing saints in Santería, gifts from his mother. His group openly fights with Black Lives Matter protesters, but he claims to support BLM’s message of denouncing police brutality, which he says should not be a partisan issue. He fights “antifa,” though says he’s anti-fascist. He shares an affiliation with men who have white nationalist tendencies, but he is Afro-Cuban and dark-skinned.

Many of his opinions go against the standard conservative grain: He supports marijuana legalization, doesn’t denounce gay marriage, and decries the privatized prisons-for-profit system.

“People think I’m right-wing, but I don’t think I am, in the mainstream sense,” he says.

When confronted about Proud Boys violence, bigotry, or any generally unsavory aspect, Tarrio always seems to have an explanation. His men “were attacked first.” “The media reported it wrong.” “The full video shows there was more” to the story.

Racist or anti-Semitic comments on his Telegram channel? He doesn’t moderate the comment sections, he explains. Besides, he says, people will say what they want.

White nationalists in the Proud Boys? Not possible, he insists. They’re disavowed under the group’s bylaws.

He repeatedly boasts about his favorite tactic when engaging with the media: “smoke and mirrors.” Ahead of a rally, he’ll announce on his Telegram channel that the Proud Boys will appear at a specific location, fully aware that reporters and opposition groups who keep tabs on the group will be listening. Then, down to the wire, he’ll flip the script.

“I did a pretty big event in Portland on September 26 [ahead of the presidential debate],” Tarrio recounts. “So what I did was I did a little smoke and mirrors and I said, ‘We’re going to go into Portland, and we’re going to clean the streets of Portland.’ And we changed locations last-minute.”

If he proclaims that the Proud Boys will attend an event clad in their iconic black-and-yellow Fred Perrys, the group will show up in plainclothes.

There was a time when Tarrio was nervous when speaking to the press. He was never in a debate club and was visibly uncomfortable in front of cameras.

Then his friend Roger Stone gave him a piece of advice.

“Always think that you’re better than the person interviewing you,” he says Stone told him.

Then he adds, “No offense.”

After his sentencing, Tarrio held a press conference in Tropical Park to discuss his jail time and the future of the Proud Boys. It was sparsely attended.

Photo by Joshua Ceballos

VI: Leaving Miami (For Now)

Tarrio’s driving his Black Tesla down Bird Road en route to his office. Mere hours after his sentencing, he held a press conference at Tropical Park. But aside from New Times and a documentary film crew that has been following Tarrio all day, no media showed up.

“Are you sad no one came to your press conference?” a documentarian in the passenger seat asks Tarrio. “No, I knew it when I let go of the [announcement] after court. I put it up late,” he replies. Then he pounds the accelerator to speed past slower-moving traffic. The documentarian laughs and calls him a dick.

A handful of supporters made it out for Tarrio’s post-sentencing address: Patricia DeBlasis, a committee member for the Republican Party of Palm Beach County and friend of Tarrio’s from campaign circles; two members of the Born to Ride for 45 motorcycle club, a Bikers for Trump group; and Souraya Faas, a local Libertarian politician and one-time independent candidate for U.S. president, another friend of Tarrio’s from his political work.

Also in attendance was Maurice Symonette, who goes by Michael the Black Man, a former Yahweh ben Yahweh acolyte and founder of Blacks for Trump. It was a Born to Ride for 45 member’s idea to invite Symonette after the pastor of Asbury United Methodist Church said the Proud Boys burning their BLM flag recalled images of the Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow.

“We need Blacks there,” one of the bikers said. They wanted to prove that Tarrio isn’t racist.

Tarrio tells the filmmaker he had prepared for the worst but the judge had led him and his lawyers to believe the sentence wouldn’t be a harsh one. With five months in jail and three years of probation to look forward to, his hopes of running in the next election cycle are dashed. He planned to bow out as Proud Boys chairman simply by not running in the group’s September 11 election, but he may have to hand over the reins sooner, as the judge ordered him to turn himself in by Labor Day.

(Some Proud Boys tell him he should stay on as chairman while behind bars.)

He’ll also have to relinquish his position with Latinos for Trump. (A week after his sentencing, he’ll announce his resignation as state director and chief of staff via Telegram.)

No one else will be able to wash the club’s image the way Tarrio does, because most other Proud Boys look like “hillbilly Vikings” who don’t know how to act in front of a camera.

Despite the admitted setbacks, by the time the documentary crew leaves, Tarrio’s already sketching out an itinerary for himself: He’ll leave by car for D.C. on Friday, September 3, making a road trip of it before turning himself in at the last possible moment.

While incarcerated, he’ll probably write a book about the past five years of his life, starting in the Trump era and then moving to his time with the Proud Boys. Then he’ll write another book, a full autobiography. At his first opportunity, he’ll run for local office. In the meantime, he says, he’ll support other Proud Boys with political aspirations.

Upon his return to Miami, he’ll go back to being a regular Proud Boy in Villain City, but with no formal leadership title. (The group may have a new spokesman by then, though a former Proud Boy says no one else will be able to wash the club’s image the way Tarrio does, because most other Proud Boys look like “hillbilly Vikings” who don’t know how to act in front of a camera.)

Tarrio wouldn’t be faulted for cracking a bit under the pressure or falling prey to cynicism.

But he seems optimistic about his own future, the future of the Proud Boys, and the outlook of the entire Trumpism movement. His enemies might believe this is the end of him, but he seems convinced the jail time will add up to a mere battle scar, just one more step on the way to the top.

“The entire movement – not just the Proud Boys – is something that’s here and here to stay, whether it keeps the MAGA name or not,” Tarrio insists. “They’re not gonna keep putting us in chains and wanting us to shut the fuck up.”

In a subsequent conversation not long before hitting the road to turn himself in, Tarrio echoes a statement from his press conference, an ominous portent of what’s to come for the establishment, both Right and Left, now that the MAGA wave has persisted in spite of the presence of a Democrat in the White House.

“They’ve had a war on their hands for quite a bit,” he says.