Miami Fine Art Gallery photo

Audio By Carbonatix

On Wednesday, April 9, video captured FBI agents raiding an art gallery in the heart of Coconut Grove and hauling away materials in cardboard boxes.

Two years earlier, real estate investor Richard Perlman and his son Matthew Perlman were strolling around Coconut Grove when they happened upon what appears to have been the same establishment: Miami Fine Art Gallery, located at 3180 Commodore Plaza.

They were immediately impressed by the large space and its extensive inventory, which included works by the likes of Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró alongside more contemporary pieces by Robert Indiana, Jeff Koons, Banksy, and others. Amateur art collectors themselves, the Perlmans were particularly struck by the number of works by Andy Warhol.

They struck up a conversation with the gallery’s proprietor, Leslie Roberts, a diminutive, nattily dressed fellow with dark, bushy eyebrows and a conspicuous toupee.

Roberts, who has said in interviews that he studied business and art history at New York University and interned at Sotheby’s, boasted about his close relationship with the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. He told them he could acquire artwork directly from the foundation for below-market prices, according to a pending lawsuit.

They purchased several Warhol pieces, whereupon Roberts allegedly proposed another idea: a joint venture to buy artworks from the Warhol Foundation, sell them, and split the profits.

The Perlmans signed on.

The trio formalized the deal in August 2023, and Roberts connected them with Alex Herman, an employee from the foundation. Herman said the foundation was selling rare Warhol canvases to raise funds for various grants and cash awards.

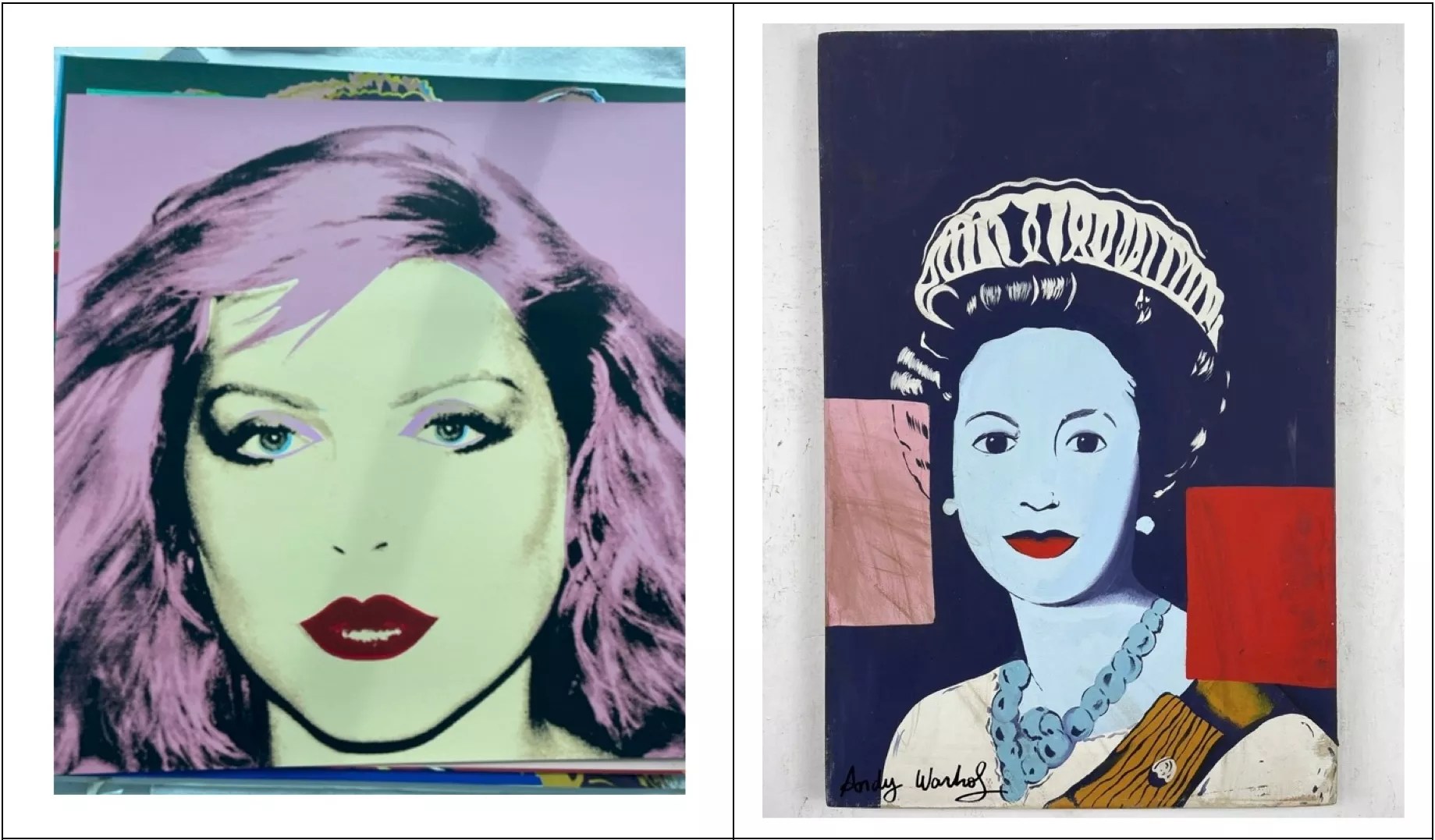

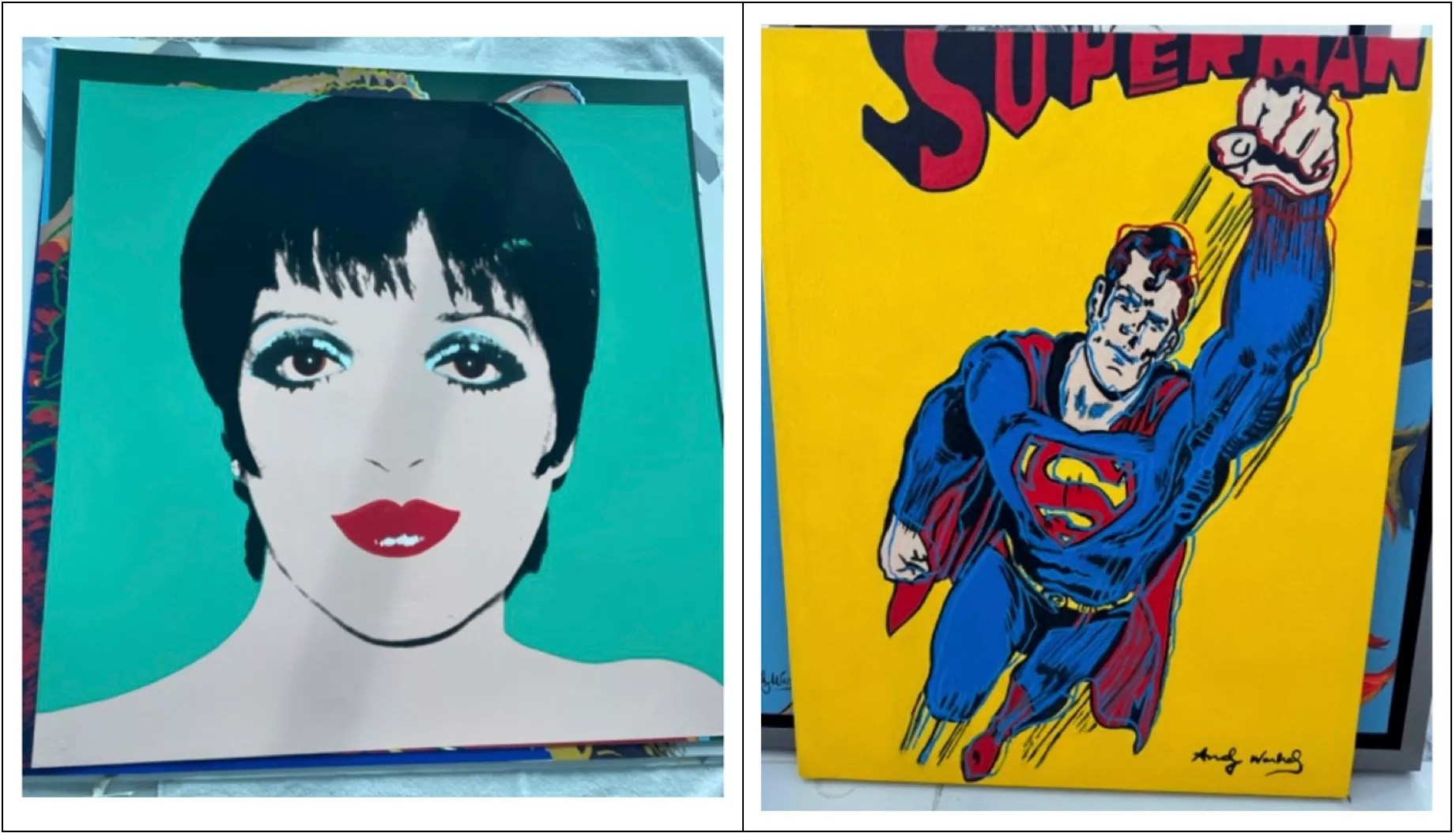

Artworks from the pending Perlman lawsuit

Exhibits via SOFLAC Associates et al. v. Leslie Roberts et al.

Four months later, the deal blew up.

Richard Perlman and his wife, Judy, say Christie’s auction house informed them the works they had purchased from Roberts were forgeries, according to a lawsuit filed in August 2024 in Miami-Dade County. They say Roberts went to extraordinary lengths to defraud them, and that they spent $6 million to purchase dozens of fake artworks.

The Perlmans allege that Roberts posed as Alex Herman and operated alex@andywarholfoundation.co, a fake email account he created to impersonate the foundation’s actual email domain, @warholfoundation.org.

That’s not all.

The Perlmans contend that after they confronted Roberts about the forgeries, he sent two specialists from Phillips, an international auction house with offices in New York, London, Hong Kong, Paris, and elsewhere, to conduct a separate appraisal.

Though the experts confirmed that the works were genuine, the family was unconvinced. They say they directly contacted Phillips, only to learn that the twosome who visited their home were not company employees and had presented fake business cards touting their ostensible bona fides.

Roberts later admitted that one of the individuals was an employee of Miami Fine Art Gallery, the Perlmans say.

“My clients are dedicated art collectors who were betrayed by a dealer they trusted,” the Perlmans’ attorney, Luke Nikas of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart and Sullivan, tells New Times in a statement. “We will continue to take every necessary step to ensure that Les Roberts is held accountable.”

Roberts’ attorney, Jonathan Davidoff, declined to answer a series of questions from New Times about the Perlmans’ allegations, Wednesday’s FBI raid, and various aspects of Leslie Roberts’ checkered past.

Robert Giczy, a retired FBI special agent who spent his three-decade career investigating art fraud and forgeries worldwide, encountered the Perlmans’ allegations when they were laid out in an August 2024 New York Times article about the lawsuit.

The modus operandi rang an eerily familiar note.

“Out of my top three art fraud cases, Les Roberts ranks right in there,” Giczy, who now operates an art consulting firm, tells New Times.

A Lifetime of Deception

Standing a tidy five-foot-three, Roberts can often be spotted cruising through Coconut Grove in his 2019 Bentley Bentayga – a ride bankruptcy filings peg at $143,000. He had big dreams for his future while growing up in Perrine, an unincorporated neighborhood off U.S. 1 in south Miami-Dade County, according to a 1986 New York Times article.

His father owned a gas station. He had a younger brother, Steve, and an older half-brother, Jeffrey, from his mother’s previous marriage. While other young teens were playing sports or watching TV, young Leslie immersed himself in books about the world’s wealthiest men or filmed movies with the neighborhood kids and later charged them admission to view the flicks.

When Leslie was 13, his mother, Clara, shot and killed his father as he slept. She was convicted of murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Leslie and his brothers went to live with their great-aunt and uncle in Miami Lakes. Though she said young Leslie never gave them trouble, his great-aunt described the boy to the New York Times as a “charming conniver” who tended to exaggerate everything.

After graduating from Hialeah-Miami Lakes Senior High School, where he distinguished himself as a talented thespian, Roberts enrolled at the University of Miami in 1980, according to the 1986 Times story. After just two semesters, he dropped out but never told his family, insisting that the movie theater where he worked paid his tuition. He also presented a fake report card with straight As.

That was 1986.

However, in more recent interviews, Leslie Roberts provides an alternate version of his childhood.

A June 2024 interview published on the art-market website Artnet.com has Roberts studying at New York University, interning at the renowned auction house Sotheby’s, and first dipping into the art market with the purchase of an Erté piece when he was 17, followed by an Andy Warhol painting a few years later.

Artworks from the pending Perlman lawsuit

Exhibits via SOFLAC Associates et al. v. Leslie Roberts et al.

“This early passion for art led me to open my first gallery in Orlando,” Roberts told Artnet. “In 1997, noticing a surge of people moving to Miami for investment and permanent residency, I saw an opportunity to cater to their growing interest in art.”

Roberts confided that one of his “proudest moments” in the world of fine art was “acquiring rare art from the Andy Warhol Foundation. This milestone underscored our gallery’s dedication to curating exceptional works.”

A December 2024 CEOWorld magazine Q&A, “Art Through the Eyes of a Visionary,” describes “Les Roberts” as “a native New Yorker turned Miami cultural icon.” He claims to have grown up in New York City, where he explored the city’s countless museums and galleries, and he reiterates his NYU and Sotheby’s résumé entries, followed by a move to Miami in 2008.

“Since taking the helm in 2008, Les has transformed the gallery into a globally recognized destination for collectors and art enthusiasts alike,” the article proclaims.

When reached by New Times, an NYU spokesperson said the university has no record of anyone by that name attending the school.

Biographical inconsistencies aside, the documented facts about Leslie Roberts paint a far different portrait than that of a genteel high-dollar art dealer.

Notably, before Roberts immersed himself in the art world, he served prison time for financial fraud.

The aforementioned 1986 New York Times story portrays Roberts as a “whiz-kid” stockbroker who defrauded his great-uncle while in his early 20s.

According to that Times piece, Roberts was working for a penny stock company when he began managing a stock portfolio belonging to a great-uncle, Frank Gory (not the same relative who’d taken him in after his mother was sent to prison for murder). Roberts took Gory’s portfolio with him when he moved on to E.F. Hutton, where he generated more than $2 million in commissions and earned recognition as the firm’s top broker.

As he raked in millions, Roberts spent lavishly. He purchased a Learjet, a Lamborghini, two stretch limousines (with chauffeurs), and a full-time gardener and housekeeper at his $1.6 million home in Boca Raton.

In November 1985, he transitioned to Merrill Lynch. Three months later, he was arrested on 19 counts of mail fraud. He was 23.

As it turned out, Roberts had depleted Great-Uncle Frank’s portfolio through unauthorized transactions, convincing Gory that his account had ballooned from $17 million to $55 million when it had actually dwindled to $8.2 million.

According to a follow-up to the Times story, Roberts pleaded guilty to three counts of mail fraud and conspiracy. U.S. District Judge James Paine sentenced him to 15 years behind bars. It’s unclear how much time he wound up serving, but the 1987 story notes that Roberts promised never to get into trouble again.

Dogged by Legal Troubles

Since 2010, Roberts has been sued at least eight times in federal and Miami-Dade County circuit courts for allegedly selling forged, inauthentic artwork or failing to deliver promised artwork from his various galleries in Coconut Grove: Miami Fine Art Gallery, VIA Art Gallery, Britto in the Grove, Max in the Grove, and Coconut Grove Fine Art. During that time, he has gone by several names, including Leslie Roberts Jr., Howard Roberts, and most recently, Les Roberts.

Roberts served 22 months in federal prison in 2015 – this time for selling forged artwork, though he again promised to change his ways. Amid the legal entanglements, he has twice filed for bankruptcy, in 2011 and again in 2023.

Three lawsuits alleging that Roberts sold forged artwork are pending in Miami-Dade County court. Two of the plaintiffs contend that they purchased the fakes after Roberts’ federal forgery conviction.

In a 2010 federal lawsuit, famed Brazilian artist Romero Britto won a permanent injunction after learning that Roberts and his wife, Silvia Castro Roberts, had sold counterfeit Britto artwork through their gallery Britto in the Grove and on eBay.

“Indeed, [Britto Central, Inc.] has become aware of at least six individuals who purchased counterfeit Britto works, believing them to be authentic originals, either directly or indirectly from defendants,” the complaint alleges.

Following his legal skirmishes with Britto, Robert rebranded his gallery to Max in the Grove. He positioned it as a destination for collectors of the German-born pop art icon Peter Max.

The name change didn’t spare Roberts from another round of criminal charges, this time in 2014.

Enter FBI special agent Robert Giczy.

Before joining the bureau’s Art Crime Team in Miami in 2000, his work had focused on Russian and European organized crime, particularly art fraud and forgery cases. Now he was called in to investigate a customer’s claim that 13 of the original 17 Peter Max artworks he’d consigned to Roberts – worth $635,000 in total – had been substituted with forged works.

Artworks from the pending Perlman lawsuit

Exhibits via SOFLAC Associates et al. v. Leslie Roberts et al.

“The name ‘Max in the Grove’ offers authenticity and credibility,” notes Giczy, who retired from the FBI and now works as a consultant. “He entertained Max in the Grove as his gallery and the studio sent him innumerable original Peter Max artworks for him to sell.”

Giczy vividly remembers his first glimpse of the customer who alleged his Maxes had been switched out for counterfeits. “He opened them up and he pulled the first one out,” the former agent recounts. “He said, ‘This is my [edition number]. This is my image, but it’s a fake.’

“I told him, ‘Seal the crate completely. I’m going to pay to have that crate shipped to the FBI office, and you’re going to fly down and we’re going to go over this.’ That’s how the case started.”

Adds Giczy: “I’ve never recovered any of those that were stolen.”

Giczy says Roberts’ ploy was to sell forgeries at discounted rates, maintaining they were the genuine articles. If victims ever questioned the quality of the artworks, the art dealer would assure them that Max probably had a “bad day” when he created it. As part of the scheme, Giczy says, Roberts copied email addresses of actual employees from Max Studio in New York and attached them to different domains.

A Family Affair

Giczy found that the forgeries were the work of Roberts’ two children, Brittney Lynn Roberts and Leslie Roberts III. Brittney pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit mail fraud, Leslie III to one of conspiracy to commit mail and wire fraud. Both were sentenced to three years’ probation.

Giczy says the forgers operated across multiple hotel rooms in an effort to evade law enforcement. “It was just a fraud to assure the buyer that it was legitimate,” he tells New Times.

The forged paintings were acrylic on canvas with certificates of authenticity, which FBI agents say they discovered were created at the gallery.

“We did have certificates of authenticity on what appeared to be the same paper, gram weight, and color of an original studio certificate of authenticity, which would list the date, title, media, the [edition number] of the artwork,” Giczy says. “But during a search, I would find pieces of paper from the computer that were cut and pasted, laid on there with tape. They were fabricated in the gallery.”

On numerous occasions, Giczy would seize his forgeries on the spot as Roberts attempted to recoup the artwork from his clients to evade the FBI.

“I would show up at a house. Les Roberts would be there loading fake art into his car, and I would come out of my car, and he would basically, kind of just really disappointedly look at me and go, ‘Hi there, officer Rob,'” Giczy says. “That happened so often that he would see me pop out of the bushes almost at every turn when he had forgeries and I would take them from him.”

Giczy says he recovered more than 300 forged Max artworks during the FBI investigation. Max Studio estimated that Roberts’ scheme resulted in multimillion-dollar losses.

“I was vacuuming the country pulling these fakes,” Giczy says.

Leslie Roberts later pleaded guilty to a single count of mail fraud. In 2015 he was sentenced to 22 months in prison, followed by three years of supervised release.

After his sentencing, Roberts’ crimes continued to cast a pall. In 2016, Giczy attended a Peter Max event at a South Florida gallery where the artist signed artwork and met with prospective buyers.

A family walked in with a Max canvas hoping to have the artist sign the piece. Giczy says he glanced at the painting and realized it was likely a Roberts forgery.

“The father came over with the two children beaming with pride and the manager goes to the dad, ‘Where did you get this piece from?’ Giczy says. “And he said, ‘I got it from a local auction.’ The manager then said, ‘May I ask you, how much did you pay for it?’ and he said, ‘Like, $6,000,’ which is not an insignificant amount of money.”

But the former fed says that particular piece would be worth three times that much if it were the real thing.

“The manager diplomatically smiled and told the father, ‘This is a wonderful piece. Please enjoy it. Mr. Max can’t sign right now. He’s tied up,'” Giczy says. “And the family left smiling.”

That scenario saddened him, Giczy adds.

“That’s what it does: The family will be impacted later; the kids; the memory. It’s on a different level beyond what the wealthy suffer, or the effect on the artist’s legacy. It impacts people differently. And I saw firsthand a family that was just swindled.”

Under his supervised release, which began in April 2017, Roberts was forbidden to own, operate, act as a consultant, or participate in any art or painting sales.

According to court documents, he violated those terms multiple times, resulting in a five-month prison stint in September 2018 and additional years of supervised release with stricter terms.

In 2021, after finally completing the supervised release period, he was permitted to re-enter the art world.

“He is free and clear,” Giczy tells New Times. “He served his time. He’s like anybody else. So he went right back into buying and selling.”

Giczy attended the Miami Beach Antique Show a few years ago and noticed a booth operated by a small gallery. He felt a tap on the shoulder. He turned to find himself face-to-face with Roberts.

“He goes, ‘Hi, Mr. Robert. How are you?’ Giczy recalls. “I said, ‘I’m doing good. I see everything is good with you.’ He goes, ‘Yes, I have a gallery now. I’m doing really well.’ Then he pointed to his [booth] and said, ‘I have Lichtenstein, Warhol.’ And he welcomed me, says, ‘Come, they’re all real. They’re all good. You can inspect them. You can look at them if you want.”’

“I thought that was just one of the most bizarre statements. And I delicately said, ‘No, it’s OK. Good luck to you.'”