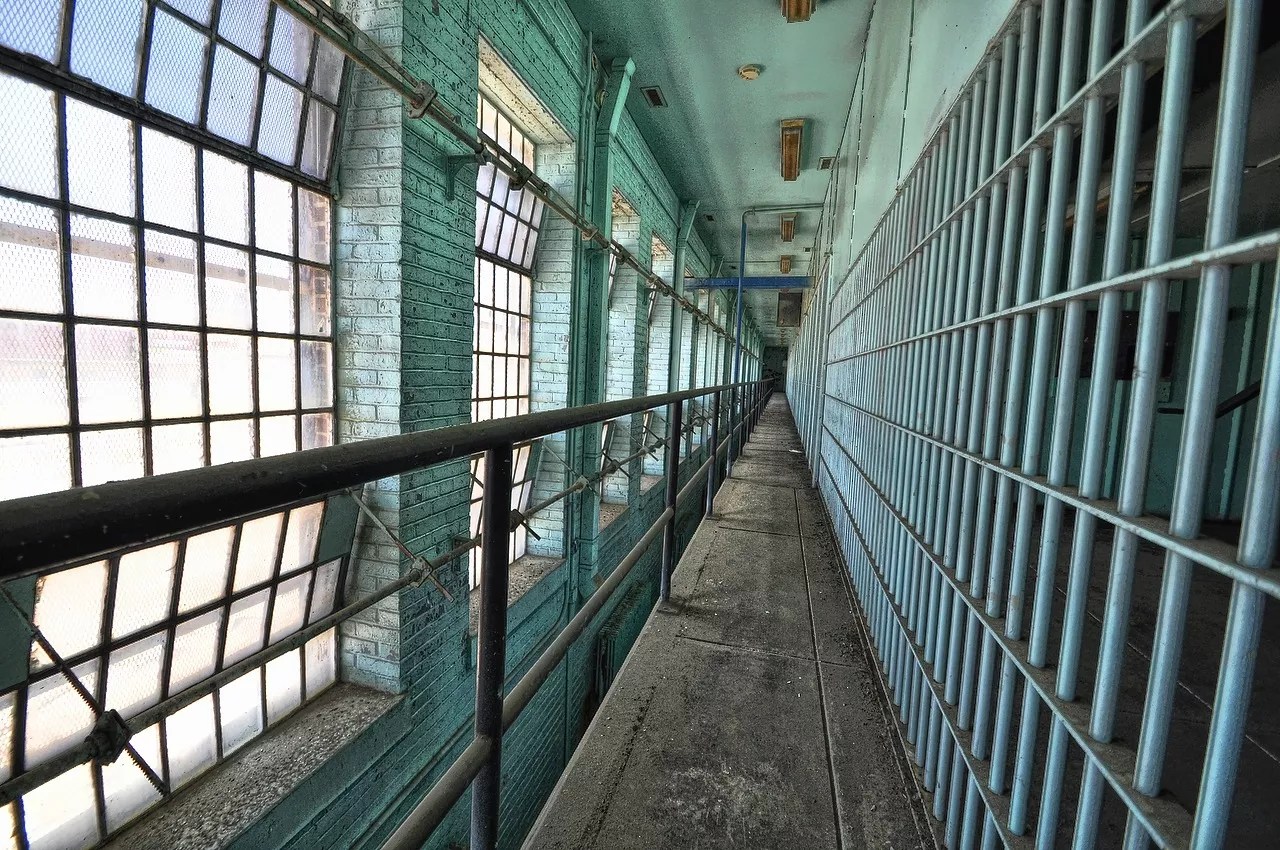

Photo by Forsaken Photos / Flickr

Audio By Carbonatix

The United States is built largely on two

And in Florida, a felony conviction permanently strips you of your right to vote. But if you’ve served your sentence, is that right? If you made a mistake and paid for it, should you forever forfeit your say in what happens in your city or state or country?

The answer is no. Which is why you should vote yes on Amendment 4.

Florida is one of three states where those convicted of felonies are disenfranchised until they are pardoned or have their rights restored by the governor’s executive clemency board. In the Sunshine State, there’s a five-year minimum wait after a sentence ends to even apply for restoration of civil rights.

Since Rick Scott took office as governor in 2011, more 30,000 applications have been received. As of last year, only about 3,000 people had their rights restored.

Derek, an attorney in Fort Myers who requested that New Times not publish his last name, was convicted of possession of narcotics back in 2006. It took him the better part of a decade to get his civil rights back. Mountains of paperwork and patience were needed. “My five years ended in 2011,” Derek explains. “After that, there was an additional four years of waiting.”

More than 1.5 million people in Florida – over 10 percent of the state’s voting-age population – have lost their civil rights due to past convictions and could regain the right to vote if Amendment 4 passes. The ballot measure, which excludes murderers and rapists, needs at least 60 percent of the vote to become law. It would bulldoze seven years of voting-rights obstruction by the Scott administration.

Preventing such a significant portion of the population from voting is a blatant throwback to Jim Crow-era laws that kept black people from the polls. While about 10 percent of voting-age Floridians are currently disenfranchised, that number jumps to over 20 percent for African-Americans. Why? African-Americans are arrested and tried disproportionately more than whites for the same crimes.

This shameful situation serves Republicans like the governor, who has spent seven years making sure that black voters, many of whom would probably vote Democratic, can’t vote at all.

In March of this year, a federal judge ruled the system Rick Scott has put in place for restoring rights had to be changed, saying it was “fatally flawed” and had “problems of potential abuse.” Judge Mark Walker, chief U.S. district judge for the Northern District of Florida, demanded that the clemency board set clear standards for restoration of rights within one month.

The ruling was overturned by a federal appeals court in Atlanta after the clemency board, which includes Scott, argued it would lead to “chaos and uncertainty.” That was a thinly veiled way of saying, “We won’t be able to keep all these people from voting anymore and we don’t want that.”

David Money of Fort Walton Beach was convicted of growing marijuana in 1994. It wasn’t until 2007 – when he learned then-Florida Gov. Charlie Crist was instituting new, relaxed standards for clemency – that Money started trying to get his rights restored. And while more than 150,000 people regained their right to vote during Crist’s tenure, Money was not among them. In fact, it took nine years before his civil rights were restored in 2016.

“I went through the whole process,” Money says. “Since then, I’ve held a federal security clearance without voting rights. I had spent 14 years volunteering… in prison… and helping guys do ministry and I had a federal security clearance, but I could not vote.”

Money’s situation points out the necessity of passing the amendment rather than counting on politicians. “Charlie Crist came in and gave everybody their rights automatically and we were like ‘All right, I guess our jobs are done,'” he recalls. “Then as soon as Rick Scott came in, one of the first things he did was take it all back away again.”

There is a difference between losing a privilege and a constitutional right. If you drive drunk and crash your car into the side of your house, you should probably lose your license. But if you are caught with marijuana, losing the right to vote is wildly excessive. It’s little more than a ploy to keep millions of Floridians from having a voice. And that runs counter to one of the essential ideas this country was founded upon.

“If this doesn’t go through, the felons of Florida need to go throw some tea into Tampa Bay,” Money asks. “Because what they’re doing is they’re taxing people without representing them. If I pay taxes for all these years, but I can’t vote for the guy that I want to represent me, that is what started the Boston Tea Party – taxation without representation.”