Photo by Jorge Martínez Gualdrón

Audio By Carbonatix

Cooper Solomon had long dreamed of being a ballerina, but when the teacher came to lead him into the studio the first day of dance class, the normally boisterous boy was quiet. The 7-year-old with big brown eyes and a gap-toothed grin stood up from the leather couch where he’d sat swinging his feet while his mom filled out registration paperwork, and wordlessly took the teacher’s hand.

The lone boy lined up beside the barre with nine girls. He was dressed the same way they were: a black leotard, black tights, and pink ballet shoes. His wavy sandy hair was pulled into a bun, just like theirs. Together, the dancers bobbed up and down in a warmup. From the lobby where his mom, Jennifer, watched, Cooper stood out only because his hair was a bit shorter than everyone else’s.

“I just hope he’s having fun,” Jennifer said, knowing he had been nervous. She’d spent days looking for the right dance company. Then she’d spent more time vetting it, calling ahead and stopping by to speak with the director in person. It was what she always did when Cooper was doing something for the first time. She knew that not every place – and not everyone – was accepting of her youngest child.

Not everyone even understood him, because Cooper didn’t fit into any of the categories the world has gradually come to acknowledge: He wasn’t gay, because he was too young to know, and he wasn’t transgender, because he identified proudly as a boy.

He fell into a different, lesser-known middle ground: He was a boy who liked girly things.

So he wore his school uniform’s skirt instead of shorts, and he primped Barbie dolls instead of racing Matchbox cars. On his Instagram account (run by his 24-year-old sister, Nikki), he shared his skin-care routine and twirled around his house to the song “Good as Hell” while watching the windows to catch his reflection. He imagined one day starring in The Nutcracker.

“Of course, he wants to be the Sugar Plum Fairy,” his mom said with a laugh. “He doesn’t want to be the prince.”

No one bats an eye at a girl who insists on wearing pants, but a boy in a dress still draws double-takes.

As society evolves toward understanding that gender identity can be more complex than simply male or female, an official term for kids like Cooper has gained traction: “gender nonconforming.” Jennifer finds the easiest way of explaining her child – which she does both frequently and patiently – is to call him the opposite of a tomboy. Though no one bats an eye at a girl who likes sports and insists on wearing pants, a boy in a dress still draws double-takes.

Yet there have always been boys like Cooper. “I think that now we just give more permission to kids to express it,” says Diane Ehrensaft, the director of mental health at a gender clinic in San Francisco and the author of The Gender Creative Child, “not just in their closets, but at their schools, in the mall.”

Life for boys like Cooper today is a far cry from the not-so-distant past, when similar kids were branded “sissy boys” and subjected to “reparative therapy” that most psychiatrists now agree left lifelong scars.

But even now, that permission extends only so far. Cooper is young enough that kids at school think it’s cool to stick up for him, and adults sometimes can’t tell he’s a boy in a dress. “I’m just Cooper,” he says.

The more he grows, the more Jennifer worries. She saw the numbers on nonconforming kids back when Cooper was a toddler who wouldn’t take off a Princess Elsa costume. She knows her child is at a heightened risk for bullying, depression, self-harm, and violence. She thinks about it all the time.

At the dance company that August day, her attention turned momentarily to two bored-looking boys waiting in the lobby, presumably dragged there because their sister was in ballet.

“Cooper is just as much of a boy as these boys,” she said. “He just expresses himself differently. If society would understand there’s no one way to be a boy, just like there’s no one way to be a girl, the world would be a better place.”

Cooper’s favorite makeup store is Sephora, where he’s most “in his element,” his mom says.

Photo by Jorge Martínez Gualdrón

Back at his family’s sprawling South Miami-Dade home, Cooper reluctantly breaks from singing and dancing to a RuPaul song called “Kitty Girl” (“Hey, kitty girl/It’s your world“) to explain, in 7-year-old terms, what being a boy means to him.

“I don’t think it’s really that different from being a girl,” he says, thinking it through. “It’s not like you’re really that different. You’re still a human. It’s not like you’re an animal in a human outfit.”

He likes girl things, he says, “because they’re pretty and sparkly.” And he knows that if his parents didn’t let him wear dresses, he would be sad.

“I would move out of the house, take my $10,” he says. Or, he decides, “I’d just tell the people at Target: ‘Could I move to Target?'”

His mom laughs.

Cooper was the fourth child for Jennifer, a nurse who quit work to become a stay-at-home mom, and Jeffrey, a chiropractor who’s now a Democratic candidate for the Florida House of Representatives. The couple, South Florida natives who married in 1992 after meeting at a medical school party, staggered their first three kids about four years apart: Nikki was born in 1994, Dylan in 1997, and Olivia in 2001.

Cooper came in 2011, when Jennifer was 39 and Jeffrey was 51. The baby was a happy surprise – one that happened after Jeffrey had a vasectomy. The family had to add another room to the house to fit him. “We like to say he was absolutely meant to be,” Jennifer says.

“If society would understand there’s no one way to be a boy, just like there’s no one way to be a girl, the world would be a better place.”

She and Jeffrey learned their baby’s sex early in the pregnancy and acted accordingly. They painted his room red and blue. They dressed him in boy-themed onesies. They placed a football next to him in baby pictures because his big brother was on the high-school team. “We were all like, ‘Oh, this is going to be so funny when he’s playing football,'” Nikki remembers.

Jennifer decorated Cooper’s first scrapbook with stickers bearing phrases such as “Boy wonder,” “100% boy,” and “When I grow up, I want to be just like Dad.”

“I did what everyone else does,” she says, flipping through the pages. “I had a boy, and his room was blue, and his toys were trucks.”

But by the time he hit a year-and-a-half, Cooper was beginning to show other interests. In scrapbook photos, he smiles in a princess gown. He wears a blanket around his head to look like long hair. He layers Nikki’s necklaces over his clothes. Then he began draping her shirts atop his T-shirts and shorts, wearing them like dresses.

Jennifer and Jeffrey had always been staunch defenders of LGBT rights and women’s equality. They were taken aback, though, by their son’s behavior. Jeffrey, who played football in high school and college, had coached their older son’s teams and imagined he’d do the same for his youngest. Jennifer knew little boys sometimes liked to experiment – trying on their sisters’ dresses or wanting their toenails painted – but this seemed different. Both parents worried about how other kids would react on the playground and in school.

They thought maybe Cooper could be steered gently toward slightly more boyish things. When they took him to Disney World to see the princesses, Jennifer dressed him in a homemade Prince Charming costume, with shoulder tassels and shiny buttons.

“But he loved the princesses,” Nikki says. “That was what he loved.”

“I don’t think it’s really that different from being a girl. You’re still a human.”

A turning point came in 2014, when Cooper was 3 and Jennifer bought him his first suit for Olivia’s bat mitzvah. She told him he could add a pink tie or a pair of sparkly shoes. But Cooper insisted he wasn’t putting on the suit, even when she reminded him this was a big occasion and his brother would be wearing the same thing.

“It was the first time I realized, This is more than just play,” she says. “And I really wrestled with it, and I wrestled with Well, I’m the parent; he’s going to wear what I tell him to wear.“

Then, one day when Jennifer was shopping at Nordstrom, a little black velvet dress caught her eye. She thought of how unhappy Cooper had been when she made him try on the suit, frowning at himself in the mirror. She snatched the dress off the rack. It was the first time she bought her little boy a piece of girls’ clothing that wasn’t a costume.

“I’ll never forget when he tried it on and he twirled around – and the look on his face,” she says. “And I said to my husband: ‘You know what? This is our child.'”

On that sunny December day of the bat mitzvah, the Solomons stood in front of all their friends and family: dad and oldest son in suits, mom and the girls in dresses, and Cooper beaming in the first real dress he’d ever owned, a dress he never wanted to take off.

It was Olivia’s coming-of-age celebration, but it was also a kind of coming-out for Jennifer and Jeffrey: This wasn’t dressup, and it wasn’t a phase. This was who their son was.

When Cooper was a baby, his parents painted his room blue and posed him with a football.

Photo by Brittany Shammas

As she and her husband began letting Cooper shop in the girls’ section and build his Barbie collection, Jennifer spent late nights scouring the internet for answers. “Boys who like girl things,” she typed into Google, and saw the term “gender nonconforming” for the first time.

She stumbled across a blog called Raising My Rainbow and read about a child in California who sounded remarkably familiar: As a toddler, C.J. had tied a blanket around his head, asked for a princess-themed birthday party, and insisted on wearing only girls’ clothes despite being certain he was a boy. The mom who wrote the blog, Lori Duran, had also authored a book about bringing up her “fabulous, gender-creative son.” Jennifer ordered it and tore through all 288 pages.

“That was the first book I read that I was like, Oh, there are other kids like Cooper out there,” Jennifer says.

In fact, there always had been. Many Native American societies had words for those who took on roles opposite their biological gender. They were accepted in most tribes and afforded sacred roles in some of them because they were believed to possess supernatural powers.

But the European settlers who began arriving in the 1500s were appalled by those traditions. They documented sightings of “effeminate, impotent” men and sometimes brutally attacked them. The belief that those who dressed or acted outside of gender norms were to be condemned took root in the earliest days of the United States and persisted for centuries to come.

In the 1960s and ’70s, psychiatrists believed boys who showed a preference for feminine toys and clothing would grow up to be gay. Government-funded experimental therapy at UCLA aimed to prevent that by instructing parents to verbally and physically punish their sons for chosing dolls over toy guns. Twenty years later, when a Washington, D.C. mother who realized the harm done to her son by psychoanalysis started a support group for “gentle boys,” her organization was so taboo that meetings had to be held in secret.

“It’s really important for boys to know there’s more than one way to be a boy,” says Catherine Tuerk, who became a leading advocate for the gender-nonconforming. “And they don’t know that. They do not know that.”

“You have to be pretty brave to live your authentic self every day with the looks and the comments that he gets.”

Only in recent years has society opened up slightly to boys like Cooper. Until 2013, the American Psychiatric Association considered a child’s “strong and persistent cross-gender identification” to be a mental illness. New guidelines now dictate that a child must feel distress over his or her gender identity for mental health to be a concern.

Many psychiatrists have moved from advocating a corrective approach, like taking away the toys and pushing the child toward social norms, to an affirmative one. That’s largely been driven by studies that have determined parental support can help shield a gender-bending child from isolation and diminished self-esteem.

“A parent will say, ‘I want my child to make it in the world, learn what the rules are, adapt to them; that’s the way the world works,'” says Ehrensaft, the San Francisco gender clinic director. “These parents love their kids and want to keep them safe. Then I point out they won’t be keeping them safe if they keep telling them who they are isn’t OK.”

Those who have lived through less accepting approaches say the damage can last decades. When Stephen Hughes was young, his mother told him little boys didn’t go outside in dresses, so he decided he had to “obliterate” part of who he was. He threw himself into sports and changed the way he walked and talked, desperate to remake himself as an all-American boy.

“Here I was hearing, ‘You need to hide who you are on a very deep level. You need to keep that a secret,'” says Hughes, who is now 54 and living in West Hollywood, California. He was hounded for decades by anxiety and depression and the realization that he had changed himself so much he barely knew who he was. He says he didn’t accept his true self until his 50s.

“I really want people to know how damaging it is,” he says. “I think some people might think, Well, big deal, he doesn’t get to play with a doll. He’ll get over it. It has bigger ramifications.”

Now acceptance is growing in a generation of parents raising families in a time when gay marriage is legal, Bruce Jenner has become Caitlyn Jenner, and Jazz Jennings, a transgender teenager, has a TV show. These parents are the first to allow boys to dress and act in ways traditionally limited to girls. Today there are mommy blogs like Raising My Rainbow and books like My Princess Boy and programs dedicated to preparing teachers and students for gender variation at school.

There are also support groups for families grappling with how to both support their nonconforming kids and keep them safe. Parents often face wrenching decisions about when and where to let their children break the norms – because despite everything, the wider world still mostly understands gender as binary: boy or girl, man or woman. Cooper’s family has felt the silent disapproval in the stares of strangers and in the comments that show up on his Instagram page.

“You have to be pretty brave to live your authentic self every day with the looks and the comments that he gets,” Jennifer says. “And he still feels so good about himself. I know as a kid I couldn’t have done it. I don’t even know if as an adult I could do it.”

Since he was a toddler, he has gravitated toward princesses and Barbie dolls.

Photo by Brittany Shammas

In early September, two weeks into the school year, Cooper’s gym teacher ordered the class to split up: boys on one side, girls on the other. Cooper froze. Which way should he go? He showed up at school with Ariana Grande-style cat ears on his head and his polo shirt tucked into a skort. All of his friends were girls. He wanted to be with them.

“You’re a boy!” one of the girls called out as Cooper stood panicked in the middle of the gym. “You have to go on the boys’ side!”

Soon the rest of the class – even the kids he considered his very best friends – joined in. The minute he climbed into his mom’s SUV that afternoon, she could tell something was wrong. “Did we have a good day at school today?” she ventured, and Cooper began to cry.

Until that day, he hadn’t encountered much conflict in the four years since the bat mitzvah marked his public debut in a dress. There were the looks at the grocery store and in the drop-off line, which Jennifer either called out or let go depending upon her mood. Cooper almost universally ignored them.

But his anguish in gym class that day was exactly the sort of painful scenario his parents had long feared and the reason Jennifer had begun worrying about middle school before Cooper even started kindergarten. And it was why she threw herself first into learning everything she could about his situation and then into advocacy and education, and has helped build a growing community of parents with kids like her son.

“I feel like if there was going to be a child put into the world like Cooper, he was put with the perfect mother,” Nikki says.

Jennifer’s advocacy began when she looked for a Miami branch of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, or PFLAG, and discovered there wasn’t one. So she started a chapter, convening monthly meetings and recruiting legislators, doctors, and school board members to speak to the group. That led to her inclusion on a committee that advises Miami-Dade County Public Schools Superintendent Alberto Carvalho on gender issues. Before Cooper started school, she arranged for the Yes Institute – a local nonprofit that educates on gender – to meet with the teachers.

And when Cooper was in kindergarten, he and Jennifer spoke at a school board meeting to ask the district to bring in a Human Rights Campaign program that trains educators to support and prevent bullying of students with gender-diverse identities. Carvalho let the then-5-year-old sit in the superintendent’s chair. A pilot of the program is now underway at two schools.

This year, she successfully pushed to have gender removed from the district’s school dress code. She has high praise for Miami-Dade County Public Schools and especially for Carvalho, who she says “feels strongly about protecting children.”

But despite all of her efforts, Jennifer still worries about how her child will be treated when she can’t be beside him. “There are times I’ve watched him walk off in that little skirt, and I go home and cry,” she says, “because it’s heartbreaking knowing that someone could make fun of him or hurt him.”

National statistics on people like Cooper suggest Jennifer has reason to worry. A 2014 survey conducted by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Williams Institute found that 41 percent of transgender and gender-nonconforming people had attempted suicide, compared to 4.6 percent of the general population. The study also showed that more than half of the gender-atypical had experienced gender-related bullying at school. Numbers like those were the footnotes to every decision the Solomons made.

“I have terrible fears,” Jeffrey confesses. “You hear awful stories.”

Even parents of gender-nonconforming kids can face frightening blowback. In July 2017, a photo of Lori Duran, her husband, and C.J. at a Pride parade somehow caught the attention of the actor/conservative Twitter troll James Woods, who tweeted it and wrote, “Wait until this poor kid grows up, realizes what you’ve done, and stuffs both of you dismembered into a freezer in the garage.”

Woods’ involvement turned the way C.J. was being parented into tabloid fodder, with strangers on the internet debating whether he was being abused. Fearing her son might overhear some of the furor, Duran didn’t turn on the TV for a week.

Last year, Jennifer and Cooper went on WLRN to talk about school safety. A man named Jose called in to tell Jennifer it was a parent’s job to explain to their children how boys act versus how girls act and to “give them the role they are.” He suggested she was pushing Cooper’s gender identity on him. It wasn’t the first time she’d heard that line of thinking. Others had told her that taking away the girl stuff would take away Cooper’s interest. She knew of pediatricians who had said the same to other parents.

There in the WLRN studio, she thought of the statistics, of the mental-health issues that dogged kids who didn’t neatly fit society’s expectations for boys and girls. Then, as Cooper sat silently beside her in his white dress, she leaned into the microphone to address Jose.

“As a parent, I could take away every bit of makeup, every girl toy, every dress, and force him to be a boy,” she said. “I absolutely could. But I also could have a child who then is dealing with a lot of issues because I’m stopping him from being who he is. I chose to have a child that is happy and healthy and living in a safe environment. And I chose not to be my child’s first bully.”

Cooper’s mom works with teachers and school administrators to educate them about gender-nonconforming kids.

Photo by Brittany Shammas

Jennifer settled onto a stool at the front of the room and faced Cooper’s class, the same group of kids whose words had brought him to tears a week earlier. She held up the illustrated children’s book Jacob’s New Dress. Chairs scraped across the floor as the students slid closer.

“Jacob ran to join Emily in the dress-up corner,” Jennifer began. “Emily slid into a shiny yellow dress while Jacob wriggled into a sparkly pink dress. They both reached for the crown, but Jacob got there first.”

When she had finished reading about the little boy who teased Jacob and the little girl who stood up for him, Jennifer turned to the children. “Do we know anyone in this class who maybe wears something a little bit different?” she asked in the patient tone of a teacher. The students said they did: Cooper.

A little girl raised her hand. “My mom always says that if you’re treating someone nice, then they will treat you nice,” she said. Another added that if someone picked on Cooper, “you could say, ‘Don’t worry about what Cooper is wearing. It doesn’t matter [as long as] he’s comfortable.'”

By the time she left the school, Jennifer felt better – and so did Cooper. After seeing his heartbreak over the gym incident, she had lain awake at night and come up with story time as a solution.

There is still more she wants to do. At home, she has copies of gender policies from Broward, Miami-Dade, and Martin Counties that she recently showed the superintendent. Martin’s and Broward’s are more thorough, providing guidance on handling everything from prom to bathrooms to substitute teachers. Miami-Dade is now working on expanding its policies.

She’s trying to link up with PFLAG groups across Florida so they can make a coordinated push for change on a state level.

Jeffrey, meanwhile, sees his latest run for state office as a chance to bring more political focus to the issue. He’s made two previous runs for the District 115 seat, in 2010 and 2012, but hopes a wave of Democratic enthusiasm might carry him to Tallahassee this time.

“We go out and advocate to change the world so people who don’t understand will begin to understand.”

If he is elected in November, he says, he wants his first bill to ban conversion therapy statewide. He wants to do it in honor of Cooper, who he says “makes me proud.”

Ehrensaft says children’s experiences vary widely depending upon which school they attend and which doctor they visit, making advocacy essential.

“We don’t sit home,” she says. “We go out and advocate to change the world so people who don’t understand will begin to understand.”

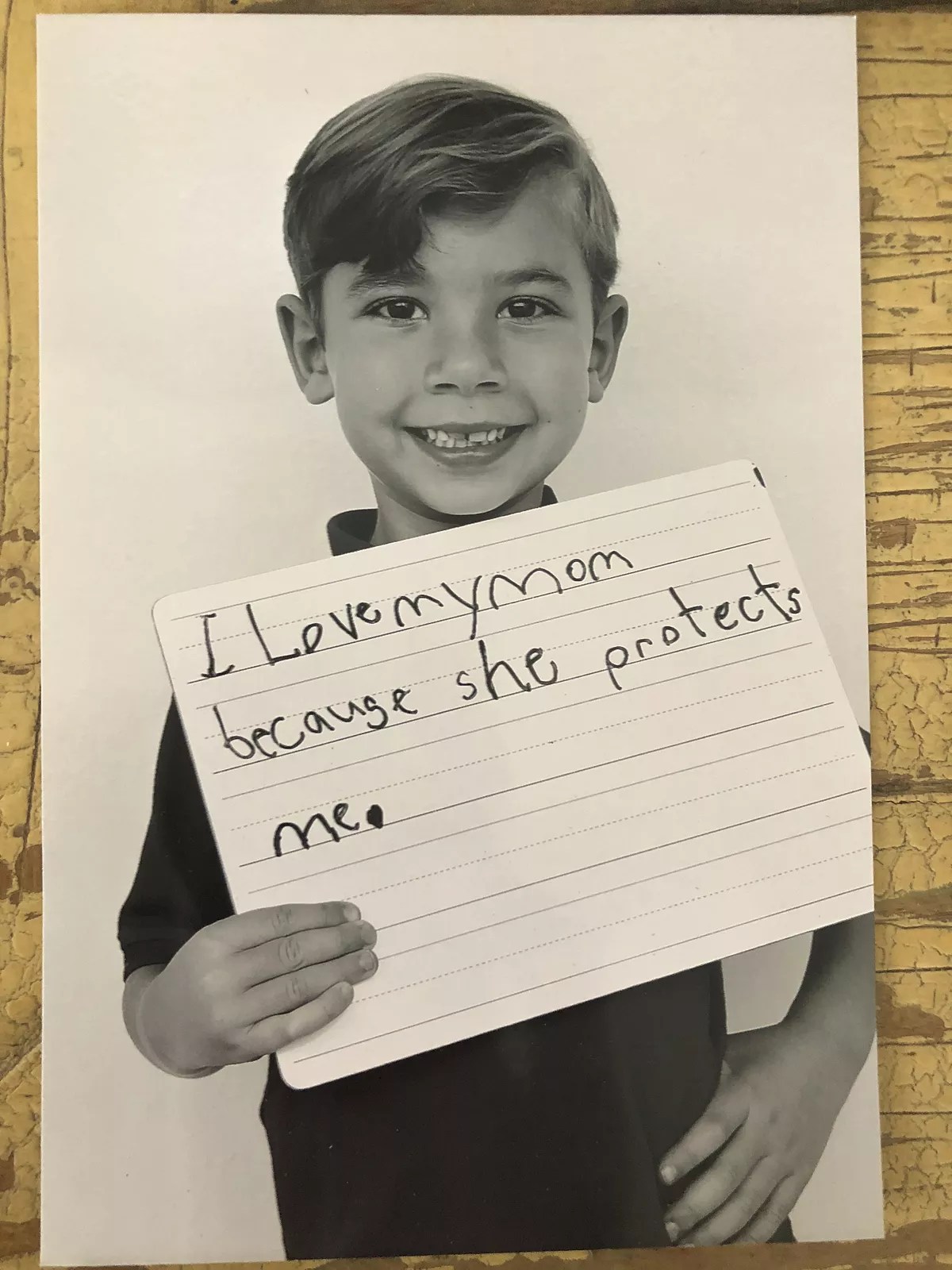

That’s the thinking behind everything Jennifer is doing. “I love my mom because she protects me,” Cooper wrote in careful kid letters for a project last year. But Jennifer knows she won’t be able to protect him forever.

“He’s little, and I can still tell him: ‘Mommy is going to make it better, and this is what we’re going to do, and this is how we’re going to do it,'” she says. “But, of course, in the back of my mind, it’s like, Well, what’s going to happen when he’s 15 and it’s a group of kids or it’s this or it’s that? I’m not going to always be able to make it better.”

Right now, though, Cooper is a precocious 7-year-old who likes to gossip about YouTube makeup stars and play with the family’s labradoodles, Lucy and Miley (whom he named after Miley Cyrus). He’s been thinking a lot about his Halloween costume – he recently switched from Shangela of RuPaul’s Drag Race to Maleficent, the Disney villain. He’s sassy and, his parents will readily admit, a little spoiled: With two of his siblings out of the house, he’s taken over several rooms. He wants to turn his old playroom into a ballet studio.

On a Saturday afternoon in September, Cooper, armed with money from a week’s worth of chores, strode confidently through a local mall. He wore the black romper he donned for picture day, plus a black hair bow and black ballet flats. He wove through the aisles in Sephora, brushing samples of eyeshadow and blush on his arm like a makeup pro and making product recommendations to his mom.

No one gave the little boy in the bow a second glance. Today, at least, he blended right in.