Photo by Scott McIntyre / ScottMcIntyrePhoto.com

Audio By Carbonatix

For a guy who once had fangs permanently bonded onto his teeth, who rose from a ring of fire for a televised audience of millions, who made the tabloids after spitting a goblet of blood in Donald Trump’s face, David Heath is actually kind of a wallflower.

When he first broke into pro wrestling, he’d have panic attacks before meet-and-greets, often picking a fight beforehand so he didn’t have to show up. In the ’90s, he got his arms tattooed with skulls and flames just to give himself a little space.

“I didn’t want to talk to people,” Heath says. “I was just trying to look mean and scary to keep people away.”

With long bleach-blond hair, buggy blue eyes, and a ladder of hoop earrings hanging from his lobes, he never had an easy time blending into the crowd. But at his core, Heath – better known as Gangrel the Vampire Warrior – hates to cause a scene.

That’s still true on a recent weekday at his new Dania Beach wrestling academy, where a couple dozen students pay a couple thousand dollars in the hopes of following his path to pro-wrestling glory. Heath can barely walk after pulling a muscle in his back at practice, but other than the occasional wince on his face, he barely lets on that it’s bothering him. He lumbers over to the stereo system, where his business partner cranks “Pour Some Sugar on Me” through the speakers to test the audio for a weekend exhibition.

“Sounds good!” Heath shouts. “Might be a little muffled, but it’s fine.”

It’s been 17 years since Heath was cut loose by the World Wrestling Federation, now known as World Wrestling Entertainment. At 49, he still has the brawny build of his youth, though his blond hair is grayer now and his memory isn’t what it once was.

Wrestling has been good to him since he invented the vampire gimmick in his early 20s. He’s traveled the world, performed on national TV, been turned into an action figure, and rubbed elbows with every celebrity in the game. Requests still pour into his Facebook inbox for Gangrel appearances, and TSA guys still recognize him when he flies to matches on the weekend. He sells hot sauce with his face on the bottle, and people actually buy it.

But the sport he loves has also exacted a heavy price. In 1999, he almost died in the ring during a stunt on WWE Monday Night Raw. After a separate injury, doctors found several “hot spots” on his brain and demanded he

“The closest other love I had was probably wrestling… It doesn’t love me, but I just keep loving it.”

Wrestling changed him in other ways too. It brought him the love of his life – his muse, his best friend – before eventually driving them apart. Without her, Heath is certain there would be no Gangrel and, perhaps, no professional career at all.

“I’d probably still be cutting grass, running heavy equipment,” he says. “Something normal, or what the world calls normal.”

Luna Vachon had been wrestling for years when Heath slowly, reluctantly fell in love with her. They got together when he was 18 and stayed together for the next 18 years.

Vachon was seven years older, beautiful and bipolar and unlike anyone he’d ever met. In spite of his shy nature, she could get him to do anything: Stroll into a gay bar dressed in leather just to get a reaction. Jump off a cliff naked for fun. Those aren’t hypotheticals, he says – they’re actual things she made him do.

“It was the only person I think I’m ever, truly ever gonna love in that kind of way,” he says. “Not that we were good for each other, but I think we were good for each other for a while.”

Heath had a way of brushing things off, but the constant travel, hard partying, and physical demands of pro wrestling weighed more heavily on Vachon. Together, she and Heath watched as friend after

It’s not lost on Heath that he’s one of the lucky ones. But he insists wrestling “owes me nothing.” He’s refused to join his colleagues in class-action lawsuits against the WWE over concussions and other health issues. Even as his own body breaks down, Heath still hopelessly loves wrestling.

Though his lifestyle has calmed, his schedule has not. On weekdays, he runs drills with students at his Dania Beach school, and on weekends, he wrestles for small crowds across the country.

Over the course of his career, Heath has done hundreds of interviews. He says his mind “never stops thinking.” But even after all these years, he still struggles to explain his relationships with Luna and with the sport that made and tormented them both.

“Those 18 years were the fastest,” he says of his marriage. “I think the closest other love I had was probably wrestling. I love it. It doesn’t love me, but I just keep loving it.”

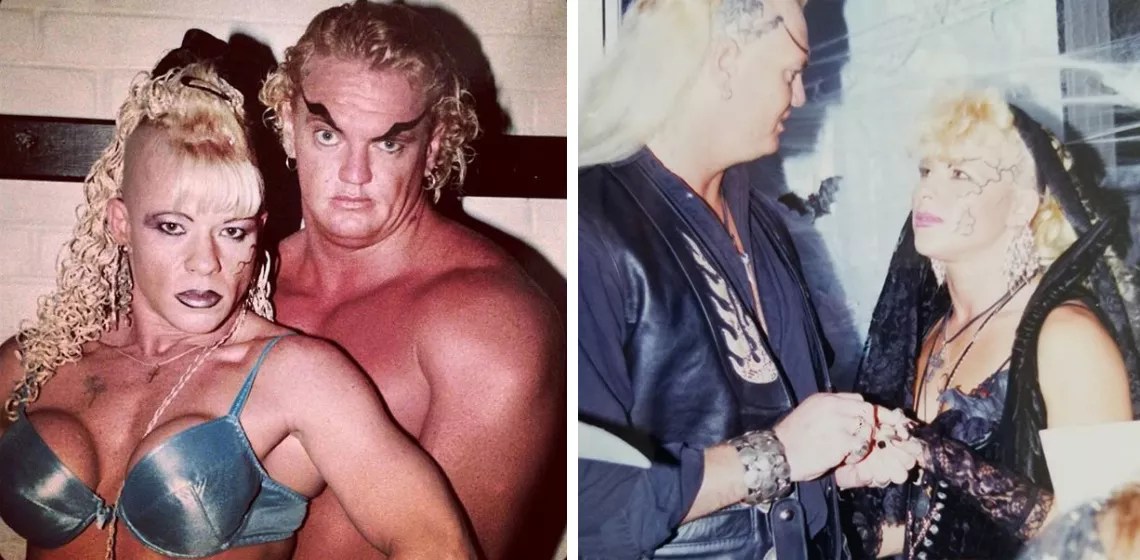

David Heath and his first wife, Luna Vachon: “I hated her. But then it turns out, I think she was my soul mate.” See more photos of Gangrel the Vampire Warrior here.

Courtesy of David Heath

In a rundown neighborhood in Deerfield Beach, Heath’s family lived paycheck-to-paycheck. His dad was a mechanic for the City of Lighthouse Point, while his mom worked at 7-Eleven and cleaned classrooms at a private school. With six kids, money was tight, but every once in a while, Heath’s parents would take the family to a wrestling match.

“As kids, we all used to go to watch wrestling live and see guys like Blackjack Mulligan and Barry Windham,” says Heath’s younger sister, Kim Heath-Miller. “It was one of the few things that my parents could afford to take us to back then.”

Heath had long dreamed of being a professional athlete. When he was in middle school, high-school recruiters began chatting him up at Pop Warner games. But just before his freshman year, he broke his neck in the championship game, crushing his childhood ambition.

After getting his high-school girlfriend pregnant, Heath dropped out of Deerfield Beach High and moved out on his own. He was working construction jobs when he saw an ad saying he could make money fighting on the weekends. The address led him to a racquetball court, where pro wrestlers Boris Malenko and Rusty Brooks offered to train him for the Global Wrestling Alliance, a Davie-based company that put on matches in Florida and the Caribbean.

To the directionless 17-year-old, it seemed the stars had aligned: He needed money, he was a fan of wrestling, and he was positive he could kick some serious ass.

“I sized everyone up, like, I can take him, I can take him,” he remembers. “I was ready to go, and it was like three weeks in when Rusty came to me and goes, ‘I gotta ask you something: Do you think this is, uh,

For all his years of watching pro wrestling, Heath had never figured out the matches were scripted. Suddenly, the entire venture seemed like a waste of time.

“It all just kind of hit me, like, ‘Oh, no, this is bullshit,'” he says. “I just couldn’t justify paying all this money to train if they’re gonna tell you how it goes and you may never make it.”

Heath was ready to quit, but Brooks talked him into staying. “You could see that he had what it takes,” Brooks says today.

In the early days, Heath stayed afloat by bouncing at the Button South, a rock club in Hallandale Beach. After his shifts ended around 6 a.m., he’d crash at the training facility, sleeping in the ring and waking up when the other students began running drills.

“Those first years, you’re paying to wrestle. You’re paying gas. There’s no money,” he says. “You’re doing it because you love it and you’re trying to get experience.”

When Heath was a kid, the wrestling business was still divided into territories run by regional companies. Wrestlers could bounce from one city to the next, pulling off the same moves and gimmick for different crowds.

But the rise of cable TV threatened the business model. In the mid-’80s, World Wrestling Federation president Vince McMahon Jr. expanded his father’s Northeast operation into a national, televised force. In 1985, McMahon put on the first WrestleMania, a pay-per-view event that pitted stars Hulk Hogan and “Rowdy” Roddy Piper against each other for the ultimate showdown – good guy versus bad guy or, in wrestling terminology, babyface versus heel.

“I go, ‘Whatever Luna is, I don’t wanna know it.’ I was scared of her.”

Heath was still breaking into the business during this tectonic shift. Just a few months after he started, he was hired for a WWF show in Florida, where he lost to Georgia wrestler Big Boss Man. But for the most part, Heath wrestled in cash-strapped regional promotions for as little as $10 a match at civic centers, high schools, and small

He was backstage at a Florida Championship Wrestling show in Tampa when he met Luna Vachon for the first time. With blood dripping from her broken nose, she swung open the dressing-room door, took one look at him, and growled, “Frrresshhh

“I was like, The hell is that?” he remembers. “I go, Whatever Luna is, I don’t wanna know it. I was scared of her.”

Born Gertrude Elizabeth Wilkerson, she came from a wrestling dynasty, the Vachon family of Montreal, Canada. Her adoptive father, Paul “the Butcher” Vachon, married her mother when Gertrude was 5 and raised her as his own. She grew up watching her uncle Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon and her godfather Andre the Giant, but her idol was her aunt Vivian Vachon, a glamorous but tough champion known as “the Wrestling Queen.”

Vachon came to Florida in her early 20s to manage Kevin Sullivan, who ran a satanic clan of wrestlers called the Army of Darkness. At a match in 1985, she was introduced as a reporter with the wrestling magazine Sports Review and then knocked out by Sullivan during a ringside interview. As her debut

“I hated her,” Heath says. “But then it turns out, I think she was my soul mate.”

When Global Wrestling Alliance shuttered in the fall of 1988, Brooks moved the operation to his backyard in Hollywood and trained students in a makeshift ring under an old oak tree. Heath began wrestling in a tag team called the Blackhearts, wearing a long black robe and creepy white face mask. His partner, Tom Nash, was the first to take an interest in Vachon, even though she was dating another wrestler, “Dirty” Dick Slater, at the time.

She’d been drinking margaritas one day when she called the Blackhearts for a ride to Brooks’ house. As they headed south on I-95, Vachon climbed into the front seat and punched Heath in the face.

“Why don’t you like me?” she shrieked.

Heath was pissed. When they got to Hollywood, he hopped into the ring to shake it off. But from out of nowhere, he felt a sharp pain in his back.

“I don’t know if she came off the ropes or just jumped through the ropes or something, but she latched down in the middle of my back like a pit bull and bit me,” he says.

He dragged her out of the ring and pushed her against the tree, but Brooks intervened. Heath let her go, then went out front and kicked out the mirrors on her car. But before the scar on his back healed, they somehow became best friends.

“She helped me understand how to be myself and accept who I am as a person,” Heath says. “She goes, ‘If they think you’re ugly in wrestling, you be the ugliest wrestler you are to make money… You take your weaknesses and make them your strengths.'”

At first, they were just friends – Heath was getting ready to marry his high-school girlfriend, and Vachon and Nash suddenly announced they’d gotten hitched.

But Vachon’s marriage lasted less than a year. Not long after the wedding, the Blackhearts got booked for a

When they returned from Japan, Heath broke things off with his girlfriend, and his friendship with Vachon eventually turned into a love he’d never felt before.

“When people always say, ‘Oh, you’re one of the first vampires,’ I say, ‘No, she was. She bit me and turned me,'” Heath says. “I couldn’t stand her until she bit me.”

David Heath debuted as Gangrel the Vampire Warrior on WWE in 1998. See more photos of Gangrel the Vampire Warrior here.

David McLain / WWE

Heath and Vachon were eating junk food and watching The Lost Boys one night when he had a crazy idea: Wouldn’t it be cool to wrestle as a vampire?

For Heath, it was just a passing thought. Back then, characters were macho men, not monsters. But Vachon was already envisioning the entire gimmick.

“She was always pushing to do it,” Heath says.

In an alternate timeline, that conversation might have been the end of the story. But while Heath was cutting grass for his uncle’s landscaping business one day, a Puerto Rican wrestling promoter came up and introduced himself.

“He goes, ‘Hey, you look like you could wrestle.’ And I go, ‘I do,'” Heath remembers. The promoter asked what his character was. “I’m a vampire,” Heath said.

That night, Heath ran to the store and bought a set of Lee press-on nails. He painted them the color of his teeth and superglued two of them to his incisors to look like fangs. He took a few headshots, sent the photos off, and got booked in San Juan two weeks later.

He was still wrestling in Puerto Rico as Lestat, the protagonist from an Anne Rice vampire

“There was a little animosity,” he says. “You’re happy, but at the same time you’re jealous.”

As Vachon’s career took off, she and Heath married in character at her Pompano Beach condo after a steel-cage match on Halloween 1994. Instead of wearing wedding bands, they got matching bite marks inked on their necks by the best man, a tattoo artist who attended in costume as a werewolf.

While his wife took on rivals such as “Sensational” Sherri and Alundra Blayze, Heath worked for the WWF as a “jobber,” a wrestler paid to lose matches. Appearing as the Black Phantom beginning in 1993, he wore a tight black singlet and a spandex mask that obscured his entire face.

In November 1994, Vachon became the first woman to appear in a WWF

“They put me in rehab because I was drinking, and then when I got to rehab, they fired me,” Vachon explained to RF Video, which produced interviews with wrestlers.

After her treatment, the WWF brought Vachon back in 1997. And in 1998, the company finally offered Heath a contract too.

By then, Heath was 29 and had been wrestling for more than a decade. Since Puerto Rico, he’d been traveling the world as the Vampire Warrior and wowing audiences with his real-life fangs, which he’d paid a dentist to bond to his teeth. But despite Heath’s numerous tryouts for the WWF, McMahon never believed in the vampire gimmick. After years of rejection, Heath had the fangs removed and began thinking of new characters.

So when he got the call that WWF wanted him to debut on its new show, Sunday Night Heat, he was surprised to hear that the creative team wanted to roll with the vampire act. The show’s writers and musicians came up with theme music, an entrance, and even his new name: Gangrel.

While his menacingly catchy song blared from the speakers, Gangrel emerged from an elevator engulfed in flames on the big

“They wanted me to be all angry, but I couldn’t,” Heath would say in a later interview. “Halfway up in the elevator, I’d just start smiling.”

As he joined forces with Edge and Christian to form a vampire clan called the Brood, he became an unexpected crowd pleaser. Fans set up tribute pages on old-school sites such as Geocities and Angelfire, declaring his theme song and entrance the greatest of all time. Like his wife, Heath became a WWF

“People would wear white shirts so they could get the blood on them,” he says.

In 2000, he broke his neck, though he wrestled for a week before telling anyone.

One of Heath’s most memorable shows came in

“You spit on Donald Trump!” one guy said excitedly.

Heath was nervous, though. McMahon, a personal friend of Trump’s, demanded a meeting but then made Heath sweat for three days. When Heath arrived at the boss’ office, McMahon gave him a stern look, then cracked a smile.

“It all came to me, that he set it up,” Heath says. “He ribbed Donald Trump, and he ribbed me.”

But amid his rise to fame, Heath kept getting seriously injured. At one match in February 1999, his opponents wrapped a noose around his neck and pushed him out of the ring. Heath thought he’d be able to grab the rope with his hands, but instead, he began to suffocate. After several seconds, one of the guys realized just in time what was happening and pushed him back into the ring.

In early 2000, Heath missed a month with an ear injury and then six more weeks after hurting his shoulder. Later that year, he broke his neck again, though he wrestled for a week before telling anyone.

While Heath kept getting sidelined, his wife was going through her own career crisis. By the late ’90s, female wrestlers had become “divas” who participated in swimsuit contests and Playboy spreads, and Vachon wanted no part of it. She began beefing with her hot young rival Sable. On the way to a match in Denver in February 2000, Vachon got a call that she’d been fired for playing a prank on a producer, something she believed was an excuse to get rid of her.

Just as Heath watched his wife rise to fame in the early ’90s, now it was Vachon who was benched at the height of her husband’s career. At their home north of Tampa, he watched her confront her insecurities in the usual way: “Depression, anger, drink, lash out, drink, abuse herself, drinking, drugs.”

He thought of her as Hurricane Luna. She’d blow in like a whirlwind and do some damage, and then everything would be peaceful while the eye passed over. The rest of the storm would move on and he’d look up, and somehow the weather was beautiful

At Gangrel’s Wrestling Asylum, Heath teaches students lessons he learned from his 30 years of experience in the ring. See more photos of Gangrel the Vampire Warrior here.

Scott McIntyre / ScottMcIntyrePhoto.com

After Heath’s release from the WWF in 2001, he and Vachon flew to Australia to face off in a pay-per-view match at the Sydney Super Dome.

Five days before their seventh anniversary, their fight for the newly minted World Wrestling All-Stars was billed as the “Black Wedding Match.” The crowd roared as legendary wrestling commentator Jerry Lawler made his introductions.

“You know, the Vampire Warrior and Luna, they put the word ‘fun’ in ‘dysfunctional,'” Lawler announced. “They’re about the most dysfunctional family I’ve ever seen in my life!”

Ringside, the organizers had left buckets of cheesy household props. Heath pushed Vachon into a fake wedding cake, and she grabbed him by the balls with a pair of kitchen tongs. She smacked him over the head five times with a baking sheet and tossed off her wedding ring. He wrapped his arm around her neck and threw her to the ground.

Despite being one of his fakest-looking matches, Heath remembers it feeling a little too real. “I was getting waylaid,” he says. “She doesn’t hit like a lady or an average woman, or even an average dude. She hits like a grown-ass, angry man.”

“You know, the Vampire Warrior and Luna, they put the word ‘fun’ in ‘dysfunctional.’ ”

After their WWF careers ended, Heath and Vachon continued to travel the world, wrestling for independent promotions. But in private, the sport was taking its toll on them. They were using cocaine and pills, then arguing about all the money they were wasting. Vachon threatened to leave, and Heath thought about it sometimes too, though he never considered it all that seriously.

“I could always walk away from anything. Her, I couldn’t,” Heath says. “She was my addiction.”

In their business, couples rarely made it. But then again, single wrestlers also had trouble staying sane. Physically, Vachon described wrestling as “the equivalent of being in a car accident every night.” In their generation, drug use was still rampant and brain injuries went largely undiagnosed.

For Heath and Vachon, their marriage became a perfect storm of jealousy, mental illness, and substance abuse. After a tour in Dubai in 2004, Vachon flew home to Florida and filed for a restraining order. Heath, who has no criminal history in Florida, denies the relationship ever grew physically violent but admits there were days they wanted to kill each other.

“We were fighting a lot; it was just the drugs. I was done with it,” Heath says. “You’re not a babyface by no means, but at the same time, enough’s enough.”

A judge ordered Heath to stay away, but he says Vachon began calling him after a few months had passed, sometimes hanging up, sometimes whispering, “I love you.” He eventually moved back in with her, but they soon settled into old patterns.

“The drugs were still there,” Heath says. “A lot of bad things happened.”

In 2005, at Vachon’s insistence, he flew with her to Phoenix for a Christian athletes conference, where they were baptized together in a swimming pool. They got saved, but it didn’t save them – in 2006, after 18 years together, Heath finally told Vachon he needed to leave.

“I know if I stayed there, where we were

Heath moved to California and married another wrestler – his way of ensuring he wouldn’t go back to Vachon. He and his ex still spoke on the phone a few times a month, but after his wedding, she stopped talking about them getting together again.

Out in L.A., Heath wrestled in independent promotions and made a brief return to the WWE in a 15-man anniversary match in 2007. Alongside California wrestler Rikishi, Heath ran Knokx Pro, a wrestling school where he trained up-and-comers such as Bulgarian sensation Rusev.

In August 2010, Heath got a call from a family friend, who said police cars were outside Vachon’s house in Port Richey. Within hours, he learned she had accidentally overdosed on drugs. Police reported crushed pills and snorting straws in her house, and a medical examiner found oxycodone and benzos in her system.

When they were still together, Heath had worried about what it would be like if he left. He worried about something awful happening to her and worried about the guilt he’d feel if something did. But when the time came and Vachon left this world, Heath didn’t feel there was any unfinished business between them.

“Between us, I know we were OK with each other no matter what, no matter what we might have said to other people,” he says. “It was a peace with each other, just an acceptance that we knew we couldn’t be together, even though we love each other and still loved each other.”

See more photos of Gangrel the Vampire Warrior here.

Scott McIntyre / ScottMcIntyrePhoto.com

When he thinks back on his life, Heath sees parallels to movies. The vampire gimmick came from The Lost Boys, while his marriage to Vachon seemed at times like Sid and Nancy. Now in his older years, the 2008 film The Wrestler resonates.

In that movie, Randy “the Ram,” a middle-aged wrestler living in a trailer, refuses to retire even as his body gives out. His love interest, an aging stripper, still dances for tips but can’t compete with her younger co-workers.

As Heath nurses his back injury in Dania Beach, he can relate.

“You’re basically a prostitute,” he says. “You’re selling your body. You’re abusing your body. You’re out there selling your soul, your body, and you’re beating it up until it’s either not pretty anymore or it’s not capable of doing what it physically used to. Nobody wants you. You get pushed aside. You slowly lower your price. You go from like a $300

After Vachon’s death, Heath tried to work things out in California but never stopped thinking about his eventual move back to Florida. His second wife was less decided: When he began looking at houses, she told him she thought their time was up. They split amicably in 2013.

Back home in Broward, Heath feels like he’s finally where he’s supposed to be. He’s grown closer to the two sons he had with his high-school girlfriend, one of whom is a father himself now. Heath’s Instagram feed is filled with pictures of outings with his grandkids and mornings at the beach.

He opened up Gangrel’s Wrestling Asylum last Halloween, a day that was once his wedding anniversary. He’s still sentimental about old times and young love.

“I’m still in love with Luna,” he admitted in an interview with a Canadian YouTuber last fall. “I’ve never felt for anyone what I felt for Luna.”

“I’m still in love with Luna. I’ve never felt for anyone what I felt for Luna.”

Heath doesn’t watch much wrestling anymore, but for WrestleMania this year, he took some students and their parents to the Hollywood Ale House to see the show. They watched guys Heath used to wrestle, like the Undertaker, and guys he trained, like Rusev.

Heath says he’s not bitter about seeing others take his place. He says he has no regrets about his life, not about his childhood football injury or being cut by the WWE or never having a “real job.”

It’s easier to accept everything because, in a way, it felt predestined. Wrestling chose him, and now he just waits to see whom it chooses next.

“You’ll come and you’ll try, and it either sucks you in and you’re all in, or you’re not. You can’t help it,” he says. “Everyone could come in here and do one line of cocaine; there’s gonna be one that’s gonna keep doing it. Same thing with wrestling. They either come in, they’re totally head-over-heels or they’re not.”

Heath was never able to wean himself off the addiction. Even today, with a gnarly back injury, he’s adamant about keeping his weekend commitment.

“What are you gonna do? Prostitute,” he says. “Just keep going.”

Two days later, Heath woke up while it was still dark and headed to the airport. A little after 5 a.m., he boarded a plane and flew to Buffalo. At a 4-H fairground in upstate New York, he snapped his fangs on and said a little prayer.

Then he climbed into the ring and gave a little more.