Illustration by Brian Stauffer

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: This is part one of a two-part story. Click this link to read “Part 2: Hard Time,” with additional contemporaneous documents and a video interview with Boast Laster.

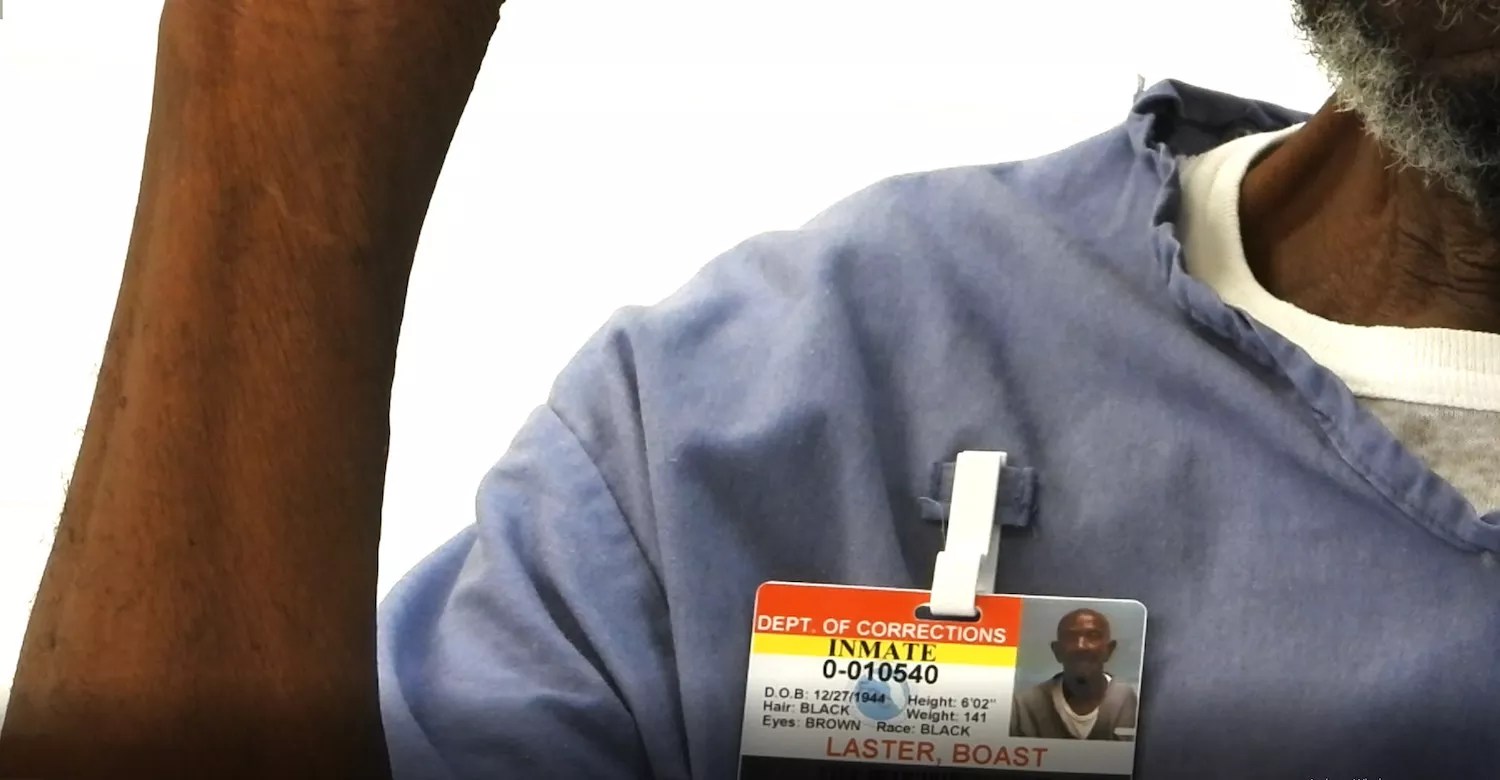

Fourteen miles west of Miami, along the luminous edge of the Everglades, a guard ushers a tall, lanky inmate into an empty room at the state prison known as the South Florida Reception Center. Gaunt, with a snow-and-asphalt beard, the man sits down at a table and gets right to the point: “I been tryin’ to do everything I could, in my power, my will, to get outta here, because I did not commit the crime.”

At age 78, Boast “Bo” Laster has spent more time behind bars than any other current Florida inmate. Yet, his name isn’t on any list of notorious criminals. No journalist has written about him since 1964. If you don’t count lawyers, Laster says, he hasn’t had a visitor since 1981.

Laster speaks softly, with a cadence from a South Florida era when “South” still described the region’s culture. “I got tired of them beatin’ on me,” he says of the 1963 confession he gave police when he was 18. “They beat me for two days. One of them said, ‘Nigger, we gonna kill you.’ Knocked four teeth out. Cracked my rib. For something I did not do.”

Six months after that confession, Laster was sentenced on February 3, 1964.

“A Florida City negro was sentenced to life in prison by Circuit Judge James W. Kehoe for the rape of a 19-year-old white South Dade housewife last July 19,” noted a brief item at the bottom of page 37 of the Miami News.

That was the last media update on Bo Laster.

I stumbled upon that article more than a year ago while browsing newspaper archives. Curious, I looked up Laster in an inmate database and was surprised to see he was still incarcerated. I asked the Florida Department of Corrections where Laster ranked in terms of time served. A spokesman said the state doesn’t track that data because inmates often cycle in and out of the system, making it cumbersome to calculate. The official sent me a list of every current inmate. I did the math. Laster is number one – a distinction not even he was aware of.

I wrote to Laster and asked if he would share his story. We exchanged letters for several months. And now here we are, face to face at the prison, with rain from the marsh drumming on the windows and a prison official seated nearby, listening in on our conversation.

As inmate No. 010540, Laster spent the decades after his conviction working hard labor. He plowed fields and worked on a chain gang – “swingin’ a pickaxe, haulin’ sandbags, all day in that sun, man” – eventually working his way up to making license plates, furniture, garments, and cooking in prison kitchens.

Along the way, he learned to read properly and began researching the law in small prison libraries. Since then, he has mailed hundreds of handwritten legal motions and letters to state courts, pleading for a new trial or some other kind of relief.

“I always said, and still say, one day God gonna open that door for me. I know this. I believe. I have faith.”

In those letters, Laster has argued that his confession was forced by beatings and should not have been admitted at trial; that the all-white jury that convicted him was illegal; that there was no physical evidence against him; that the rape victim never identified him as her attacker; and that a life sentence for rape is cruel and unusual punishment.

Time, meanwhile, has been no ally. Documents with which Laster could support his claims have been destroyed; witnesses and lawyers have died. Now, his advancing age makes recalling details and arguing the complexities of his case a challenge.

Moreover, thanks to a draconian Florida law passed in 1885, sentencing reforms that should have set him free decades ago don’t apply to him.

Yet Laster remains hopeful. He points to a thick metal door 20 feet away, across the bare interview room. “I always said, and still say, one day God gonna open that door for me,” he asserts. “I know this. I believe. I have faith. I done did 60 years. But out them 60 years, I have learned and I have grown to believe in the Almighty. And one day, I’m gonna walk out that door a free man.”

Boast “Bo” Laster, inmate No. 010540

Photo by Terence Cantarella

Florida City, 1963

Around 11 p.m. on July 19, 1963, a young newlywed couple parked beside an abandoned rock pit in Florida City, Dade County’s southernmost and most rural municipality. The pit, a well-known Lovers’ Lane, was full of cool water on a hot summer night. Earlier, the couple, identified by pseudonyms in this story – though their names appear in case documents, their identities were not included in contemporaneous police reports or news coverage – had gone for a swim. “Nicholas” and “Mia,” ages 28 and 19, sat chatting in the car. The sky was overcast and the area was unusually deserted for a Friday night.

Just after midnight, a beam from a flashlight lit up the car’s interior.

“Police,” a man said and asked to see a license.

Nicholas caught a glimpse of two men standing behind the light. They looked too young to be officers and weren’t in uniform. They were also Black, and there were no Black cops in Florida City at the time.

Nicholas quickly rolled up the window, started the car, and tried to drive away, but the back wheels got stuck in a palmetto thicket. As he tried to free the vehicle, a large rock crashed through the driver’s-side window, cutting his face. He shouted for Mia to run, then followed her out the passenger door.

“Get her and I’ll take care of him!” one attacker yelled to the other, according to a statement Nicholas later gave police.

One of the men swung an ice pick, leaving a gash in Nicholas’ shoulder, and hit him on the head with a rock. Having lost sight of Mia in the darkness and fearing for his life, Nicholas ran across an open field to a house. He called the police, then raced back to the rock pit with two men from the house.

The attackers were gone. So was Nicholas’ wife.

Lucy Street Bar

A few miles away, 18-year-old Boast Laster was shooting dice against a wall outside the Lucy Street Bar, a popular Black hangout. He was drunk. A lot of people were drunk. There wasn’t much else to do in a farm town on the weekend.

In 1963, Florida City was a remote, agricultural community of some 4,300 residents. “Up in Miami” there were beaches, nightclubs, and tourists. “Down in Florida City” there were beans, limes, and tomatoes. Segregation was still legal. But in Dade County’s only majority-Black municipality at the time, discrimination was less of a daily hassle in Florida City than elsewhere.

“It was a good life,” Laster recalls. “Everybody knew everybody ’round the neighborhood. You could go to Mississippi and back, leave the doors open. Ain’t nobody gonna go in your house and take nothin.'”

“Daddy” Laster worked at a fruit-processing plant and was a deacon at a Baptist church. “Mama” was a housemaid well known for her ham hocks, black-eyed peas with rice, and sweet potato pie.

They’d adopted “Bo,” their only child, as an infant. His birth parents lived in Georgia and had more kids than they could care for. So, Laster says, he was given to family friends. When the Lasters moved to Florida City shortly after adopting him, he lost contact with his biological parents and siblings.

By 1963, Bo should’ve been in the 12th grade but was held back a year because of his poor reading skills – a common result of the substandard quality of education at underfunded, segregated schools.

What he lacked in literacy, however, Bo made up for in speed.

After school, he’d change into his baseball uniform and jog two miles along Florida City’s dirt backroads to the next town over. In Homestead, population 9,100, the St. Louis Cardinals operated a facility that served as a spring training camp for many of its minor-league affiliates.

A year earlier, at 17, Bo had seen the players practicing and thought: “I can do that.” He walked up to a coach and announced he was faster than any current players, then raced around the bases against a stopwatch to prove it.

“When can you start?” the coach asked.

“Right now,” he said.

“It was a good life [in Florida City]. Everybody knew everybody ’round the neighborhood. You could go to Mississippi and back, leave the doors open.”

Laster says he landed a spot on a team as an infielder, showed up every day for practice, and began dreaming of the big leagues.

On the weekends, though, he liked to drink. His uncle, a moonshiner, gave him his first taste of alcohol at age 15 and got him hooked. When drunk, he’d walk right into trouble: He got into fights, broke into a sandwich shop one night, and at 16, took part in an armed robbery.

That last stunt landed him at the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, a state-run juvenile reform institution in Marianna, in the Florida Panhandle, that would later gain infamy for staff-inflicted beatings, rapes, and murders of students. Bo spent 18 months there. He says he received minimal academic instruction and that he was regularly whipped with leather straps for minor infractions in an upstairs room in a building on the Black side of campus.

When he returned to Florida City, Bo went back to school, worked part-time for a grocer, and focused squarely on baseball. The Cardinals, he says, told him he was about to be offered a contract. All the while, he tried unsuccessfully to stay sober. His long-term girlfriend, a devout Christian who’d stuck by him while he was at the boys’ school, didn’t approve of liquor. According to Bo, she hoped they’d marry one day, and the bottle wasn’t part of her plans.

The bottle, however, would put an end to those romantic dreams.

Laster maintains that on the night of the rock pit attack, he walked his girlfriend home, kissed her goodnight, then headed to the Lucy Street Bar around 9 p.m. He’d already had a few drinks with friends earlier in the day. Now, he just wanted one more.

At the bar, rhythm and blues poured from the open windows. Patrons danced. Laster shot dice out in the muggy air with Reid Bryant, a 21-year-old who worked as a bottle-capper at the local Coca-Cola plant. Laster had seen him around town, and they bonded that evening over the game. Sometime after midnight, they heard an argument erupt inside and shots fired from a gun. The bar emptied as everyone scattered into the night, on foot and in cars. They weren’t just fleeing bullets. They were fleeing the cops, who they knew would show up and start throwing people into squad cars.

The two men jumped into Bryant’s car and went careening down the road, around a bend, and straight past a parked Homestead cop.

Moments later – at 12:26 a.m., according to a police report – they were sitting in the back of that squad car in handcuffs. Bryant was arrested for reckless driving, Laster for public drunkenness.

Mia Returns

Around 1:30 a.m., a U.S. airman stationed at Homestead Air Force Base was driving two miles north of the Florida City rock pit. He spotted a young woman walking along the roadside in the rain. She looked distressed, so he stopped to see if she needed help. She told him her name and said she wanted to go home.

Mia’s husband was waiting at their Florida City home with detectives. Police records show that she told a terrifying tale.

After Nicholas ran for help, the attackers caught her and carried her to their car, which was parked nearby. One man sat in the back seat with her. The other drove. When they reached a secluded area, the driver stopped and climbed into the back. He held her arms over her head while the other man pulled up her skirt and raped her.

The driver then returned to his seat and began heading to another location. The back door, however, wasn’t securely shut and swung open. Mia saw an opportunity to escape and bit her rapist on the hand. He cried out and let go of her. She jumped out of the car and ran into a wooded area.

The two men briefly searched for her, but she eluded them in the dark until they gave up and left. Dazed, Mia made her way to a main street, where she was spotted by the airman and driven home.

Based on the couple’s descriptions, police put out a BOLO (“Be on the lookout”) for the suspects, then took Mia to Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami for evaluation. In a report submitted to police, a doctor noted a one-inch laceration next to her left eye. DNA and rape kits didn’t yet exist, so he could only determine that she’d recently had intercourse and listed her condition as “fair.”

A Confession

Laster and Bryant spent the night in a municipal jail while detectives worked the rock pit case. In the morning, Bryant bonded out.

Laster, however, was transferred 36 miles north to the county jail near downtown Miami. He sat in a one-man cell for the rest of the day, wondering why he’d been sent up north on a simple charge of drunkenness.

The following day, July 21, Laster recalls, two Metro-Dade detectives took him to an interrogation room and told him he was a suspect in a rape. (Police records show that Laster’s name had come up as a potential suspect during the night.) Their theory was simple: Sometime before midnight, he and a friend left the Lucy Street Bar and made their way a mile and a half to the rock pit, spotted a lone car, and decided to rob the occupants. When they saw a pretty female, they abducted and raped her, then returned to the bar until a gunshot sent everyone running.

Boast Laster mug shot, original (L) and digitally enhanced image

Original image from Metro-Dade police file

They told him Nicholas had identified him and Bryant from their mug shots.

Laster denied any involvement in the abduction and rape. The detectives, he says, held a gun to his head, called him the N-word, and beat him so badly they knocked out four teeth and cracked a rib.

The interrogation continued all day and late into the night until, at 12:50 a.m. Monday, Laster sat down with Metro-Dade Det. Larry Foreman and stenographer Gertrude Pfau and formally admitted his and Bryant’s guilt.

Laster doesn’t recall the stenographer arriving to record his statement, and it’s unclear whether she was in the same room with him. A surviving transcript of that wee-hours confession, however, confirms her participation.

“I said I did it ’cause I wanted to stay alive. At the boys’ school, kids got killed. If them teachers could do it, I figured the cops could kill me too.”

“I was scared, man. I said I did it ’cause I wanted to stay alive,” Laster says. “At the boys’ school, kids got killed. If them teachers could do it, I figured the cops could kill me too.”

In the morning, Laster’s father came to see him. “I know you didn’t do it,” Laster recalls him saying.

His dad asked the police to treat his son’s injuries. Laster says a sergeant provided gauze for his missing teeth, then shackled him and took him to the hospital, where he was given a wrap for his rib. (A 1975 prison document confirms that Laster had missing upper teeth and was provided false ones. It doesn’t specify when or how he lost them.)

That afternoon, after his confession, prosecutors charged Laster and Bryant with rape, a capital offense in Florida at the time. A grand jury indictment followed a few weeks later. If found guilty at trial, the defendants could die in the electric chair.

A “Scandalous” System

Laster and Bryant needed a good lawyer.

In 1963, however, capital crimes in Florida were not handled by vetted, salaried attorneys from a professional public defender’s office, as they are today. Back then, if someone facing the death penalty couldn’t afford counsel, judges appointed a private attorney to defend them.

Those appointments were not highly sought-after. Attorneys were paid $500 per case (roughly $4,800 in 2022) – a small sum for the time and effort required to prepare a credible defense. Some of those appointed weren’t even criminal defense attorneys.

“The judges selected court-appointed counsel from a group of mainly civil lawyers,” says veteran Miami attorney Roy Black, who has practiced civil and criminal law in Florida since 1970. “Most of them were not experienced in criminal defense [and] were greatly underpaid for the heavy responsibility they were asked to undertake. I don’t need to mention the irony of appointing the least-experienced lawyers defending the people charged with the most serious crimes.”

In 1966, the Miami Herald reported findings by the ACLU, which had labeled Florida’s system of appointing subpar private attorneys to capital cases “scandalous” and noted that the $500 appointment fee sometimes “doesn’t buy much defense at all.”

Yet Laster and Bryant lucked out. They drew Philip Carlton, a talented 33-year-old who had established a reputation as an excellent criminal defense attorney after only four years in practice. Carlton won acquittals in several difficult death-penalty cases through preparation, showmanship, and a commanding courtroom presence. Before his death at 89 in 2019, he’d go on to achieve near-legendary status within the Miami legal community.

During the ensuing five months, Carlton worked with Laster and Bryant while they awaited trial in the county jail. Laster never spoke with Bryant during that period because they were kept on separate floors, but Carlton met with them individually. Their trial date was eventually set for Monday, January 6, 1964.

Four days before the trial, Laster’s luck ran out.

At a hearing on January 2, Carlton asked Judge James Kehoe to separate his clients’ trials so that Laster’s confession wouldn’t prejudice the jury against Bryant, who had not confessed. The judge agreed and appointed Laster a new attorney. Then in a surprise move, the judge scheduled Laster’s trial ahead of Bryant’s, giving Laster’s new attorney only those four days to prepare.

Reid Bryant mug shot, original (L) and digitally enhanced image

Original image from Metro-Dade police file

While there’s nothing unusual about last-minute motions to sever codefendants’ trials, it’s highly unusual that a newly appointed attorney would proceed to trial on such short notice. Most criminal lawyers would ask for a continuance to prepare the case. Some judges, however, appreciate lawyers who are always ready for trial, whether prepared or not, so they can clear their dockets faster.

Michael Zarowny was one of those always-ready lawyers.

A 48-year-old former Miami Beach cop, Zarowny cut an imposing figure in the courtroom. He was six feet tall and weighed 250 pounds, with a shaved head and a loud voice. But his stature didn’t translate into success for his clients, according to people who remember him.

“[He] did not enjoy a good reputation as an able defense lawyer,” recalls a longtime South Florida attorney who spoke on the condition that his name not be published. “I didn’t know him personally, but my impression was that he was a poor lawyer who lost practically all his cases. Zarowny was well-known for doing very little work on his cases.”

A second lawyer, who had tried a case with Zarowny and who also provided background information, says, “I was never impressed by him at all.”

“My impression was that he was a poor lawyer who lost practically all his cases. Zarowny was well-known for doing very little work on his cases.”

Old news articles paint a curious picture of Zarowny’s life and career. On the one hand, they show that Zarowny was elected head of the Florida Criminal Defense Attorneys Association in 1967. On the other, they show that he was arrested three times for reckless driving while drunk and had to be subdued during two of the incidents because of his “violent behavior.” Another article, titled “Zarowny’s Career Here Marked by Turbulence,” noted that the former football player was arrested for the “brutal beating” of a 66-year-old parking lot attendant while he was an assistant county solicitor. Zarowny was acquitted at trial for lack of evidence. He was later accused of “pushing around” a deputy sheriff.

Laster recalls that Zarowny met with him only once before his trial: “He told me we’d be going to court pretty soon. I said, ‘Pretty soon? You don’t know nothin’ about my case.'”

“I know a lot about your case,” Zarowny purportedly responded.

“That was it,” Laster says. “I didn’t see him no more until I went to trial.”

The jury consisted of 11 men and one woman. All were white. Worse for Laster, the state prosecutor was Gerald Kogan, a former national college debate champion who’d won nearly all his cases since joining the Homicide and Capital Crimes Division four years earlier. In fact, the year before Laster’s trial, Kogan’s division won all 31 cases it prosecuted. Kogan would later rise to division chief and, eventually, attain the state’s highest legal office: chief justice of the Florida Supreme Court.

Kogan wasn’t just good, he was practically unbeatable.

The Trial

If there’s a transcript of Boast Laster’s trial, it’s not on file at the court clerk’s office. The judge, the prosecutor, and Zarowny are dead. Additionally, the few newspaper reports about Laster’s case conflict with existing court records and police statements, including the times of the attack and Laster’s arrest. Some news accounts erroneously reported that Nicholas was beaten unconscious. Others identified Laster as a farmworker. One claimed Laster was part of an anti-integration, Black Muslim group whose members swore to “kill a white man – preferably a policeman.”

One news report claimed Laster was part of a Black Muslim group whose members swore to “kill a white man — preferably a policeman.”

Screenshot via newspapers.com

Laster insists he was never part of any group and was never a Muslim. As proof, he points to a faded Star of David tattoo on his arm.

George Newman, a young reporter in 1963 at the now-defunct Miami News, wrote the first story about Laster three days after the rock pit attack. Newman doesn’t remember the case but recalls that such stories usually came to the newspaper via a phone call from the police. “If they made an arrest down in the Homestead or Florida City area and they wanted to get credit in the press,” he says, “they’d call and say, ‘We’ve got an arrest down here,’ and I’d put on my headset and write the story.”

A rape case involving two ordinary citizens would not have justified a trip by Miami reporters down to Florida City to interview witnesses or family members. The police version of events was often the only version available. That changed, however, once Laster’s trial began. Reporters from the Miami News and the Miami Herald attended the proceedings and produced eight short articles about the trial. By cross-checking Laster’s recollections with those articles and available court documents, it’s possible to reconstruct key events from the proceedings.

Two facts become clear in the picture that emerges: There was no physical evidence on which to convict Laster, and no potentially exonerating evidence was introduced.

Other Suspects

The problems began with the identification of the suspects.

According to police reports, Mia said her attackers were both roughly five feet ten inches to five feet 11 inches tall and weighed 175 pounds. Laster was six feet two inches tall and weighed 150 pounds. Bryant’s height and weight were not officially recorded, but Laster says he “was real short.” Two witnesses who knew Bryant and saw him at the Lucy Street Bar described him to police as a dark-complexioned man who stood just five feet tall and weighed between 100 and 120 pounds.

Reports show that Mia described her attackers’ car as a white over chocolate brown four-door with a Continental kit, (an upright, externally mounted spare tire behind the trunk). Bryant drove a white over pink two-door ’54 Ford Victoria with no Continental kit.

The driver, Mia told police, wore a white-and-red-striped shirt and (“possibly”) dark brown pants. Bryant wore a gray suit and white shirt that night. The man in the back seat, Mia said, wore a white shirt and (“possibly”) black pants. When police arrested him, Laster was wearing a green shirt and green-and-brown-striped pants.

Despite the discrepancies, Laster says, detectives told him during his interrogation that the victims had identified him and Bryant from mug shots. Two early news reports at the time claimed Mia also had identified them in a lineup. Yet police files contain no evidence that Mia ever identified her attackers. In fact, at a pretrial hearing on August 6, 1963 (17 days after the attack), she was unable to point them out. And at trial, on January 6, 1964, she reiterated that she couldn’t identify them because she wasn’t wearing her glasses at the time of the attack.

She did, however, notice that one of her attackers had a scar nearly an inch and a half long under his right eye, according to a statement she made soon after the attack. Police reports mention no such scar on either Laster or Bryant, and none is visible in their mug shots.

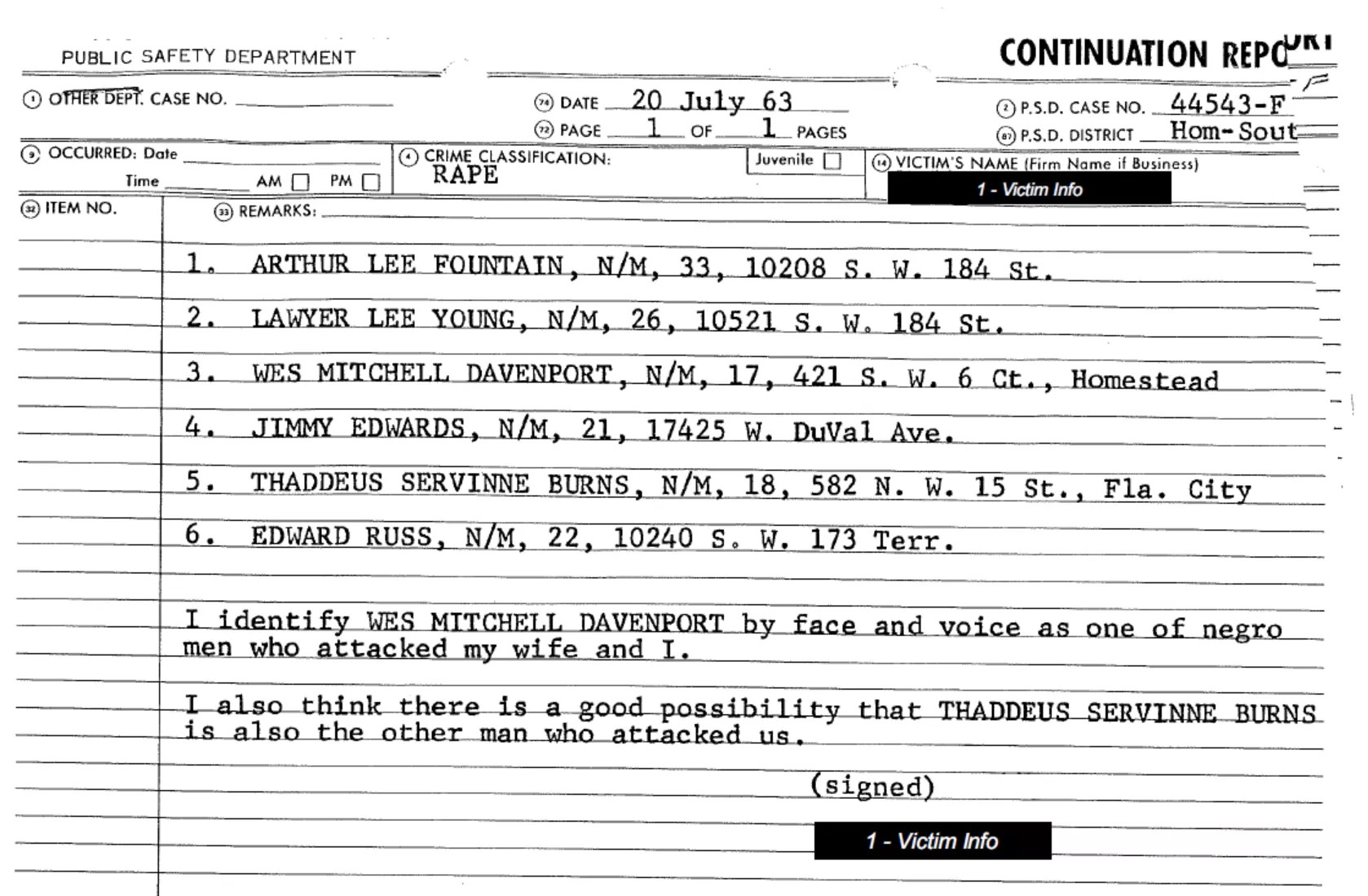

A day after the attack, “Nicholas” picked two men out of a lineup that contained neither Laster nor Bryant.

Metro-Dade police file

At that same pretrial hearing, according to the Miami Herald, Mia’s husband was adamant that Laster and Bryant were the attackers. When asked to identify the suspects, Nicholas pointed a finger at them and shouted, “Both of those two right there! I could never forget those two faces as long as I live.” Later, at trial, he pointed at Laster and said, “Without a doubt, that’s the man. He knows in his heart he’s guilty.”

Yet police reports show that just a day after the attack, Nicholas implicated two different men. Shown a lineup of five young Black men, he first picked out a 17-year-old Homestead youth. His signed statement reads, “I identify Wes Mitchell Davenport by face and voice as one of the negro men who attacked my wife and I.”

Next, he chose an 18-year-old Florida City man: “I also think there is a good possibility that Thaddeus Servinne Burns is also the other man who attacked us.”

The following day, July 22, Nicholas selected Laster and Bryant from a new lineup. Mia viewed the same lineup and selected two entirely different men. (Laster does not recall being placed in that lineup.)

Those four other suspects were not the only ones.

Nathan Graham, a 29-year-old airman at Homestead Air Force Base, was seen two nights before the attack, driving with “an oscillating red light similar to the ones used in detective units,” according to police files. Graham’s car was a 1956 Studebaker that fit Mia’s description of her attackers’ car, which was a cream over chocolate brown four-door with a Continental kit.

Graham was taken in for questioning the day after the attack and charged with impersonating a police officer. Mia was brought to see his car and immediately identified it as the one in which she was assaulted. “She showed the spots that she claimed were her blood on the back seat and the hump she remembered in the middle of the back seat,” reads a police report. “She identified it by color, grill, interior, and by the small dent on the driver’s side of the door.”

Two facts become clear: There was no physical evidence on which to convict Laster, and no potentially exonerating evidence was introduced.

Neither Mia nor Nicholas recognized Graham, however. He was released and deployed to Korea shortly thereafter.

The night Graham was seen flashing a police cherry, he’d been with Donald Darling, a man “known in the south end as a mugger and a robber,” according to police. On the night of the rock pit attack, he had been in the Lucy Street Bar with 26-year-old Mack Newsome. A witness said Newsome confided that he and Darling were going out to “get some white pussy” and if that witness told anyone, he’d stick an ice pick up his ass. The witness claimed Newsome said Laster was going with them.

The witness was 17-year-old Wes Mitchell Davenport – whom Nicholas had identified the day after the attack along with Thaddeus Burns.

Further complicating the case, the man who’d found Mia walking in the rain and driven her home called police the day after. He said an 18-year-old named Norman Lee Hodges had told him he knew who the attackers were: Davenport and Burns. The files contain no information about Hodges’ identity or how he became involved in the case, but he, too, became a suspect. Documents state that he was “shown to Mia,” who did not recognize him. But a day later, Nicholas contacted police and said that “he now believes that perhaps his wife could identify Norman Hodges” as one of the attackers. She never did.

Though it’s unclear how police settled on Laster and Bryant, they focused on no one else once Laster confessed.

Yet 17 days before Laster’s trial began, two additional suspects appeared.

Screenshot via newspapers.com

On December 20, 1963, while Laster and Bryant were in jail awaiting trial, two young Black men attacked a white couple parked at a rock pit in nearby Naranja. According to two news reports, the attackers shone a flashlight into the car, ordered the couple to get out, and robbed them of $55. Then they locked the man in the trunk and raped the woman.

Despite the striking similarities in the two crimes, Laster says he was never made aware of the incident. The Rules of Evidence, which bar lawyers from mentioning other crimes at trial under most circumstances, likely prevented it from being discussed. No further information about that incident or the culprits appears to have been preserved.

Witnesses for the Defense?

Despite the problems, Michael Zarowny didn’t call a single witness to testify in Laster’s defense or to corroborate his contention that he was at the Lucy Street Bar at the time of the attack.

Laster says his father had rounded up several people who were at the bar that night and introduced them to Philip Carlton and, later, to Zarowny. The witnesses, he says, were willing to corroborate his alibi.

Laster claims he saw some of them sitting in a hallway outside the courtroom during a break in his trial, and when he asked why they didn’t come in to testify, they said Zarowny told them to come to court but never called on them.

Similarly, Zarowny had called no witnesses in a high-profile murder case five years earlier, despite the willingness of several to testify. That defendant, who received a life sentence, was exonerated seven years later.

Zarowny’s defense strategy mostly rested on Mia’s inability to identify Laster. It also relied on a lab report. Laster’s, Bryant’s, and Mia’s clothing, including their underwear, had been submitted to a police crime lab, along with the cloth cover from Bryant’s back seat. An analysis found no semen or blood on any of the items.

Zarowny presented that report at trial and, Laster says, prodded Mia about whether she’d actually been raped – a common tactic at the time. Prosecutor Gerald Kogan countered the findings by pointing out that the emission of semen isn’t a necessary component of rape.

“Zarowny,” Laster says, “just seem like he weren’t even tryin’.”

Evidence

What evidence, apart from Nicholas’ shifting identification, did the state have against Laster?

Mia said she bit one of her attackers on the hand, and Laster had a scar on his wrist. The prosecutor, Laster says, pointed to it as physical evidence of his guilt. But the scar had come from a school fight a year before the rock pit attack. “Boy had a knife and I tried to take the knife and he hit me across the wrist. I had to have stitches put in,” Laster says. “That ain’t nothing like no bite mark.”

The Metro-Dade Police Department’s investigative file didn’t mention any wounds when Laster was taken into custody. It only noted Mia’s assertion that she bit her attacker “on the back of his left hand.” Laster’s old scar, though, was on his “inner right wrist.” Today, that scar is still faintly visible. Despite all this – the prior injury, the wrong shape, the wrong location – the prosecutor kept bringing it up at trial. “I kept saying, ‘It’s old, it’s old,'” Laster says.

The scar on Laster’s right wrist was one of many inconvenient truths that went unquestioned at trial.

Photo by Jade Finlayson

On the stand, Laster addressed the most damning evidence: his confession.

He’d confessed because of the police beatings, he said, and pointed to his four missing teeth. But the detective who’d led Laster’s interrogation, Larry Foreman, also took the stand and denied the accusation, claiming Laster’s teeth were missing at the time of arrest.

Zarowny asked Foreman to submit to a lie-detector test, but the judge denied the request, according to a report in the Miami News. In the end, it came down to the word of a Black juvenile delinquent against that of a white police officer.

But what did Laster actually confess to that night at the station?

According to the police transcript, he confessed that his friend Reid Bryant threw a rock through the victims’ windshield, but police reports show that it was the driver’s-side window that was smashed.

At the trial, “Mia” was unable to identify either of her attackers.

Screenshot via newspapers.com

It shows he confessed that he raped Mia in her car at the rock pit, but Mia said she was driven away in the attackers’ car and assaulted at a different location.

It shows that Laster said Bryant held Mia’s legs while he raped her, but Mia said the other man held her arms over her head.

It shows that Laster said he left Bryant alone with Mia in the car, but Mia said she was never alone with the second attacker.

What do these discrepancies mean? Did Laster intentionally muddy details to create doubt about the validity of the confession later?

Laster says he was frightened and confessed to the story detectives fed him. If he got any of the details “wrong,” no one said so.

Nor was he asked to explain any wounds while giving that confession. If he’d had a fresh bite mark on his wrist, he points out, why wasn’t it on the record?

“I was tired and hurtin’,” he says. “They told me I was gonna fry but could get some mercy with a confession and be out on parole in a few years. So I said what they told me to.”

Guilty, Not Guilty

The defense rested on the third day. Jury deliberations lasted an hour and 45 minutes. The verdict: guilty with a recommendation of mercy.

Under Florida law at the time, a guilty verdict meant an automatic death sentence. If seven out of 12 jurors recommended mercy, however, a judge could choose between death and a life sentence that included the possibility of parole.

Three weeks later, Laster’s judge sentenced him to “hard labor for the remainder of [his] natural life.”

A week after Laster’s sentencing, Reid Bryant went to trial. The media didn’t cover the four-day proceedings, and no transcript is available. A single, 152-word article appeared in the Miami Herald on February 14, 1964, a day after the trial ended.

Bryant’s attorney, the gifted Philip Carlton, had come prepared. According to a statement he gave the Miami Herald, Carlton calculated that his fee amounted to 25 cents an hour.

Bryant was acquitted.

This is part one of a two-part story. Click this link to read “Part 2: Hard Time,” with additional contemporaneous documents and a video interview with Boast Laster.