Photo by Gary Monroe

Audio By Carbonatix

Miami Beach native Gary Monroe spent decades traveling the world with his Leica film camera, photographing everyday people and places including Haiti, India, Trinidad, Cuba, Brazil, and Poland. Closer to home, his lens captured some of Florida’s most overlooked communities – from the elderly Jewish residents of South Beach in the late 1970s, to Little Haiti in the 1980s, to a secluded group of sex offenders in St. Petersburg in the late 2000s.

Today, his life’s work – a cache of 22,000 prints and 12,000 rolls of film – is housed at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Library archive.

As Krome North Service Processing Center, widely known as Krome Detention Center, has returned to the spotlight amid reports of overcrowding and poor conditions under the Trump administration’s latest mass deportation efforts, New Times spoke with Monroe – who spent a year photographing the notorious federal immigration facility between 1981 and 1982 – about his time documenting the center and the detainees held there.

While Krome was originally built in the 1960s as a missile base, the government repurposed it in the 1980s, during the Mariel boatlift, to house and process Cuban and Haitian immigrants. At the time, a joint Cuban-Haitian Task Force operated the site, which it used to detain up to 2,000 people.

In 1982, the facility officially opened as an immigrant detention center. As reporters fought for access to what was then known as the INS Krome Detention Camp, Monroe was regularly on the ground there with his Leica, documenting the daily lives of the detainees inside.

Krome Detention Center (1981-1982), by Gary Monroe

Krome Detention Center is at the edge of the Everglades, where nondescript cinderblock buildings encroach on the river of grass. The 1980 Cuban flotilla brought 125,000 refugees to Miami from the port of Mariel. Krome was the official point of entry. It was a testy, redefining year, and things were just getting started.

About 30,000 Haitian refugees (also known as Haitian boat people) arrived by boat on the heels of the Marielitos. They, though, came without an effective lobby and were largely unwelcome. While the Cuban immigrants could assimilate, the Haitians lingered at Krome.

By the mid-1970s, South Beach had become a community of Jewish retirees. Miamians shunned the area, which was anything but a place of fun-in-the-sun tourism. The popular television show Miami Vice and artist Christo and Jean-Claude’s Surrounded Islands became key markers for the re-emerging city. On these shifting grounds, a serendipitous photograph of a young Haitian man gliding on his bicycle by three older adults on their morning chores availed the opportunity to photograph other immigrants’ beginnings on these golden sidewalks.

I then photographed Haitians recently released from Krome to the Metropole Hotel at Sixth Street and Collins Avenue, which the government had leased for temporary housing. In previous years, the hotel was a bastion for Hasidic Jews.

Soon, I drove out to Krome. At the guardhouse, a uniformed official with his hand on his rifle turned me away. Three weeks later, I met with camp director Cecilio Ruiz. I showed him a box of South Beach prints sprinkled with 50-cent art words, and he told me to cut to the chase; he was a busy man.

I asked for unrestricted access to the camp for a year. He told me I could photograph anyplace I wanted, except at the camp jail, as he hurried away. I stopped him and asked why; after all, he barred the press. Mr. Ruiz said he got what I was doing, that I was not a photojournalist, and he had nothing to hide.

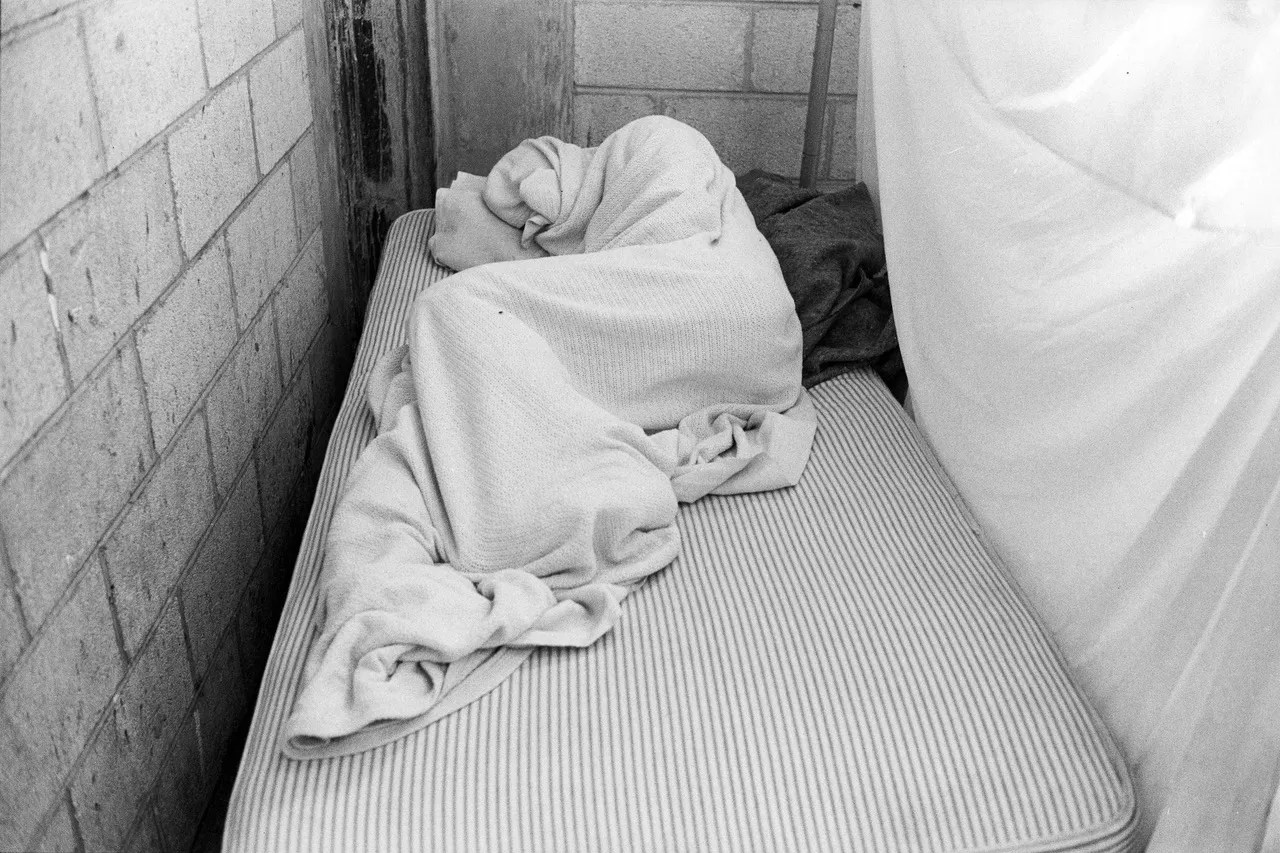

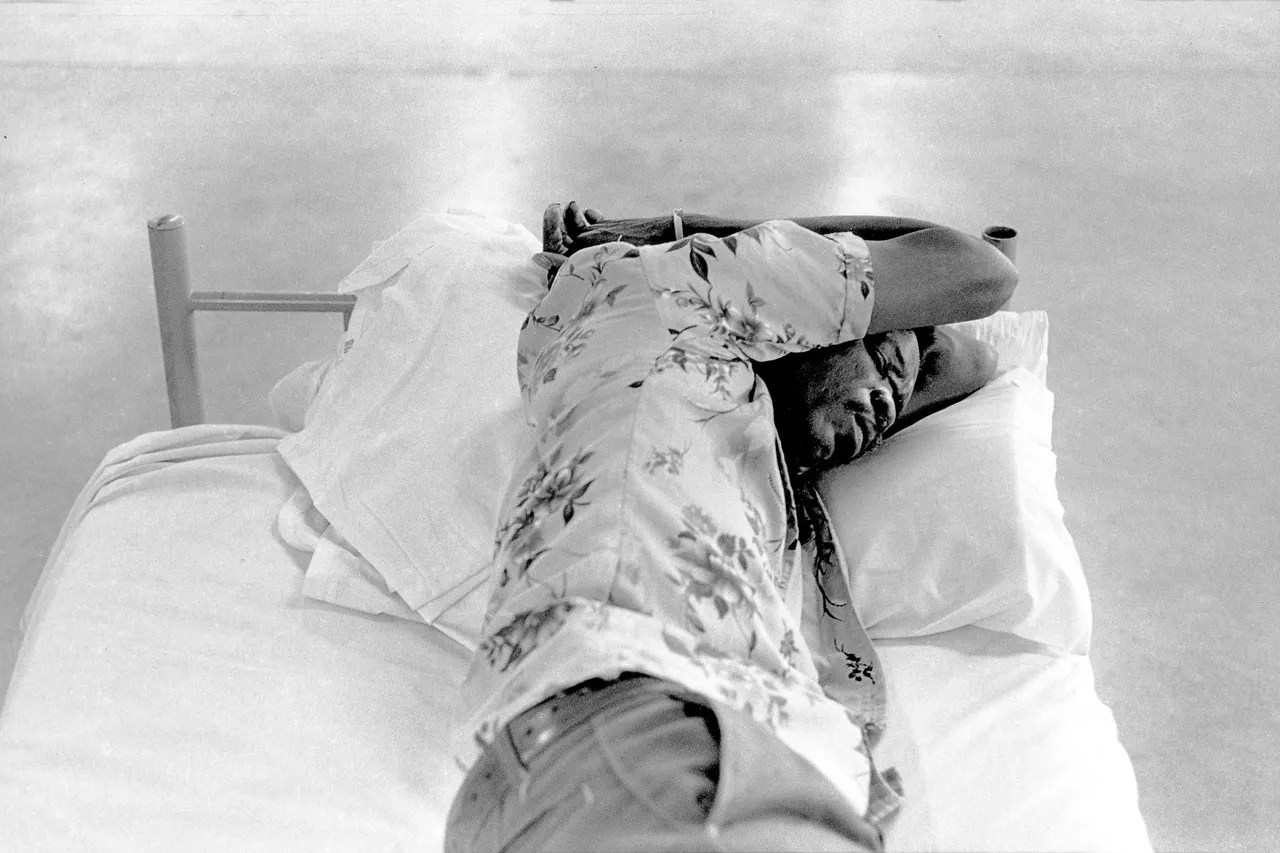

A person sleeping inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

Men lying on a bed inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

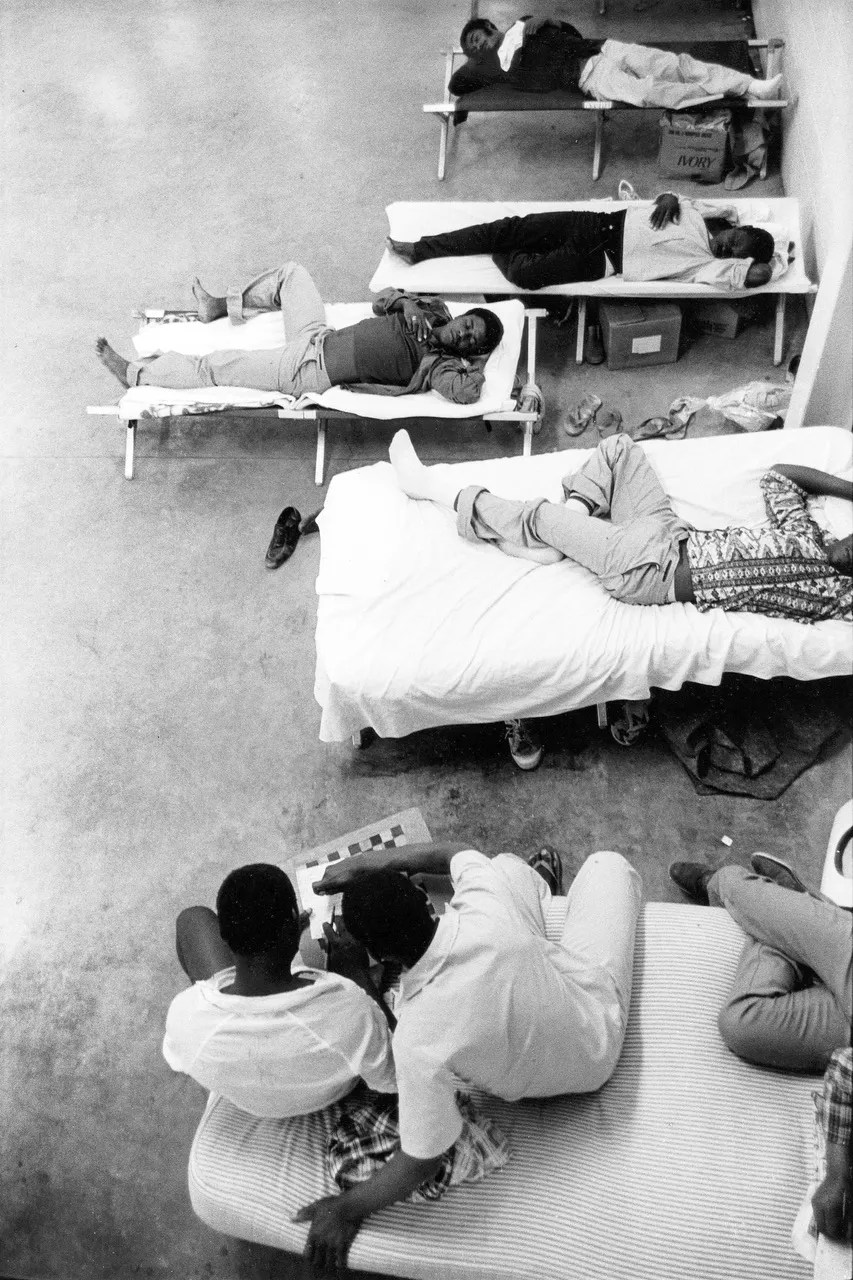

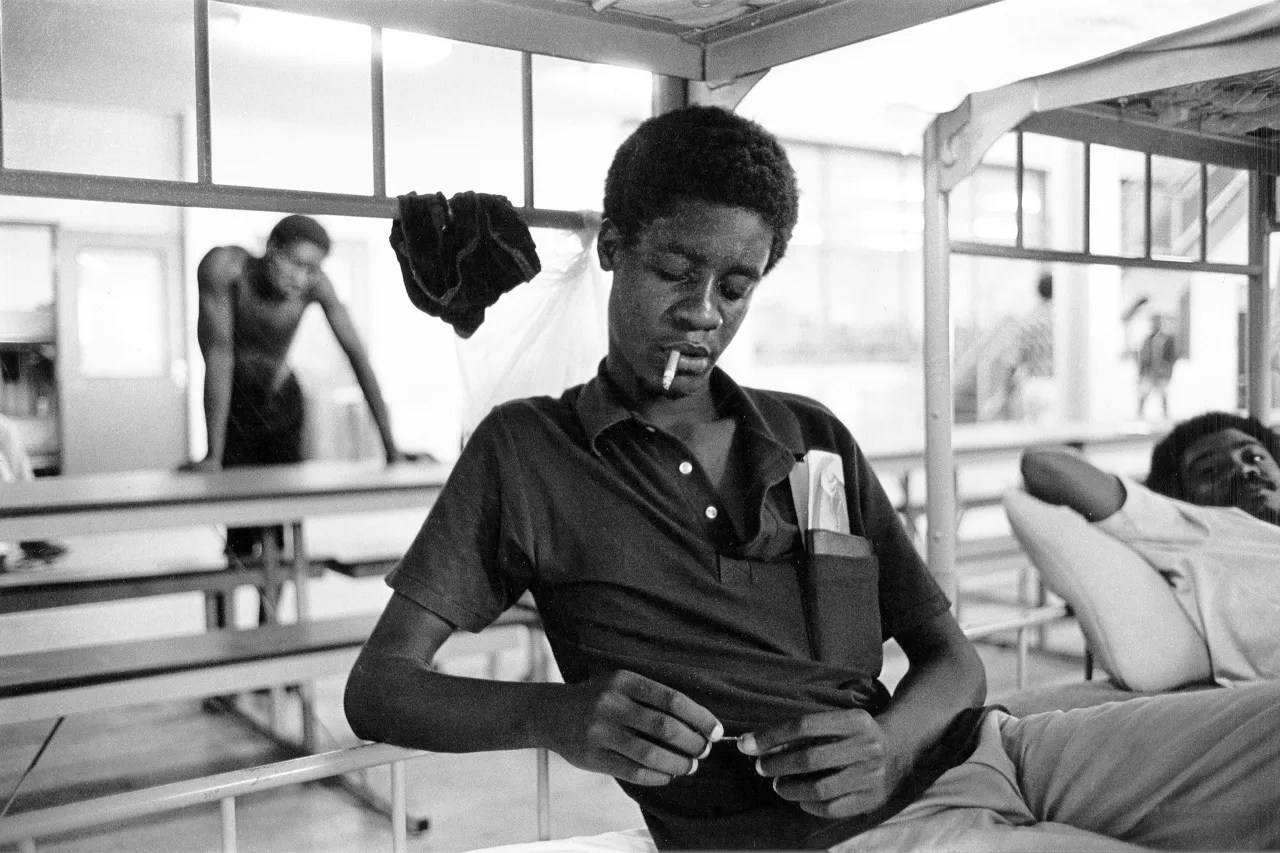

Detainees passing the time inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

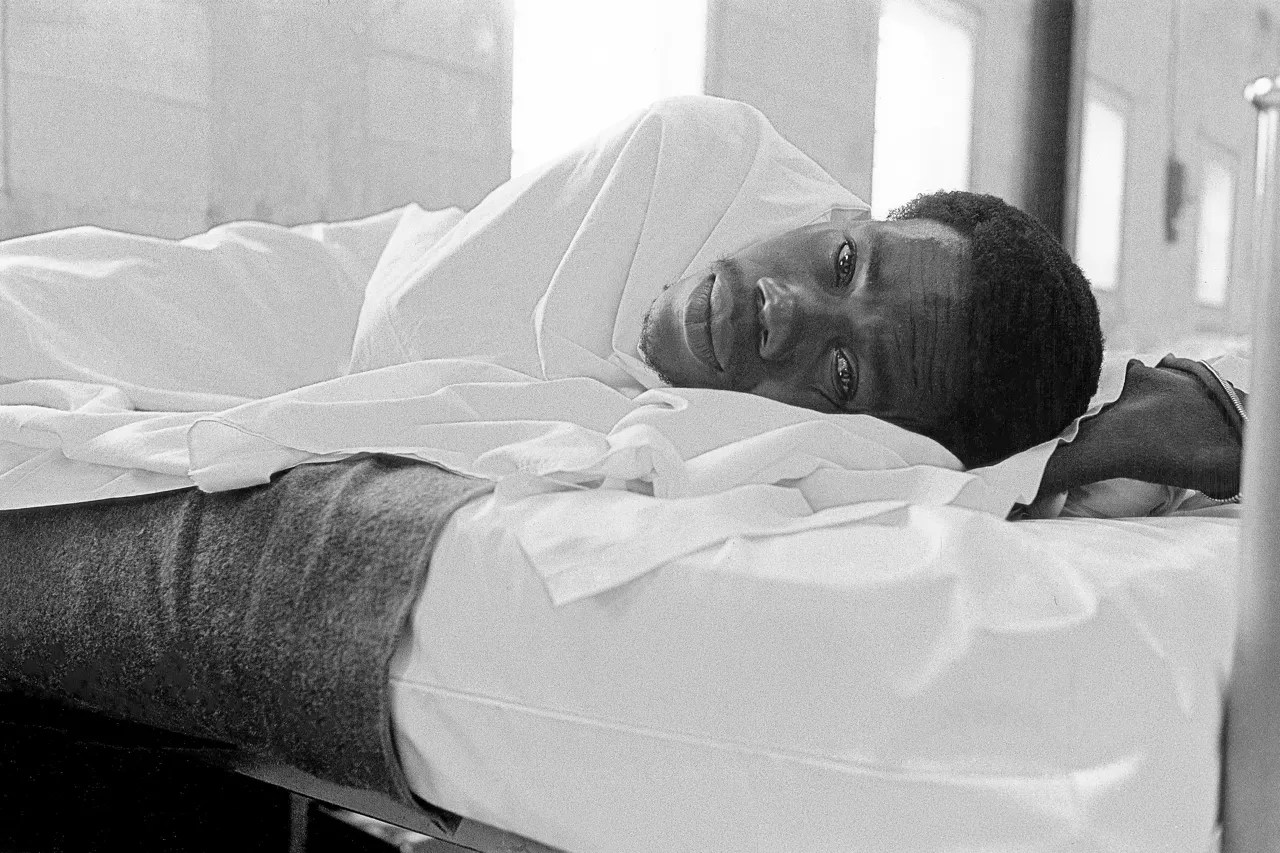

A man lying in bed inside Krome Detention Center.

Photo by Gary Monroe

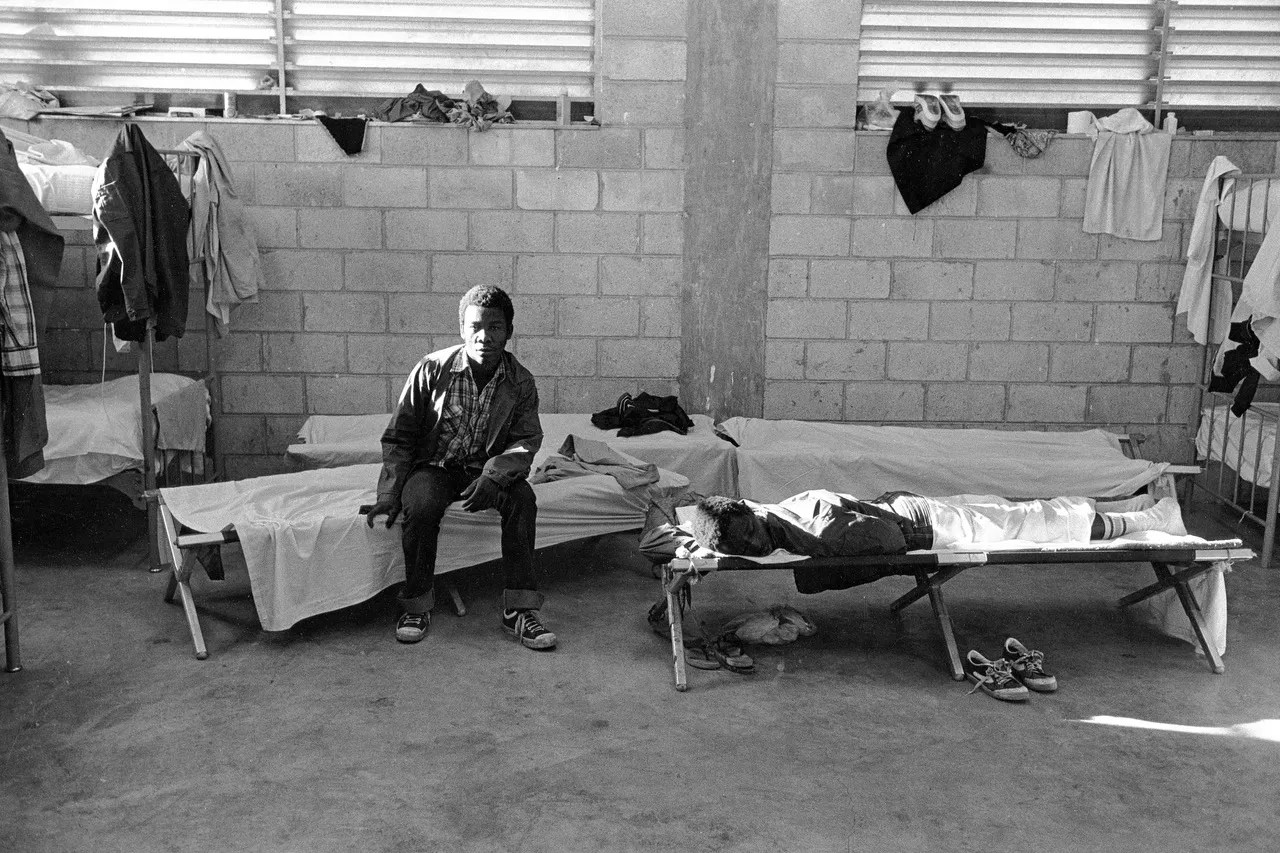

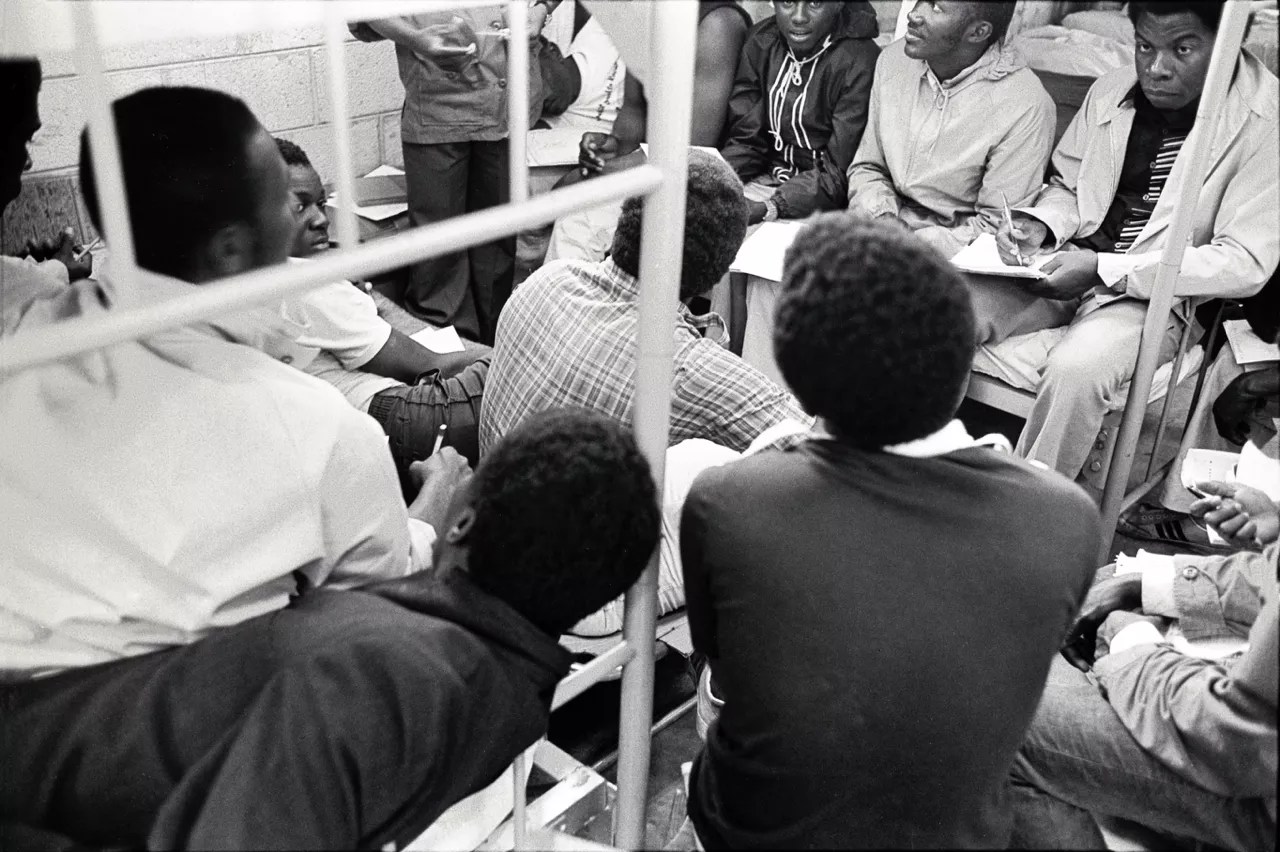

Male detainees sitting on beds inside what is now known as the Krome Detention Center.

Photo by Gary Monroe

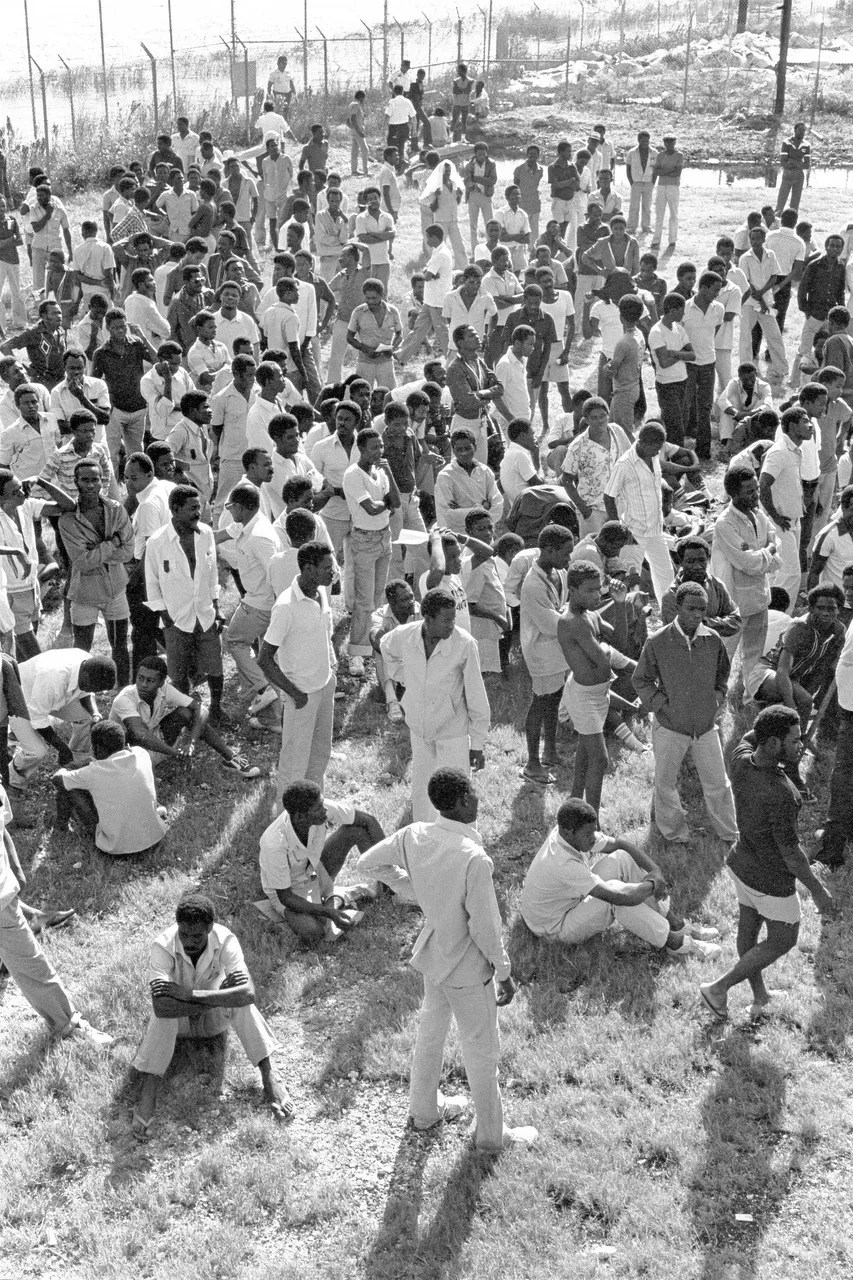

A crowd of detainees gathered outside.

Photo by Gary Monroe

Detainees sleeping on foldable cots.

Photo by Gary Monroe

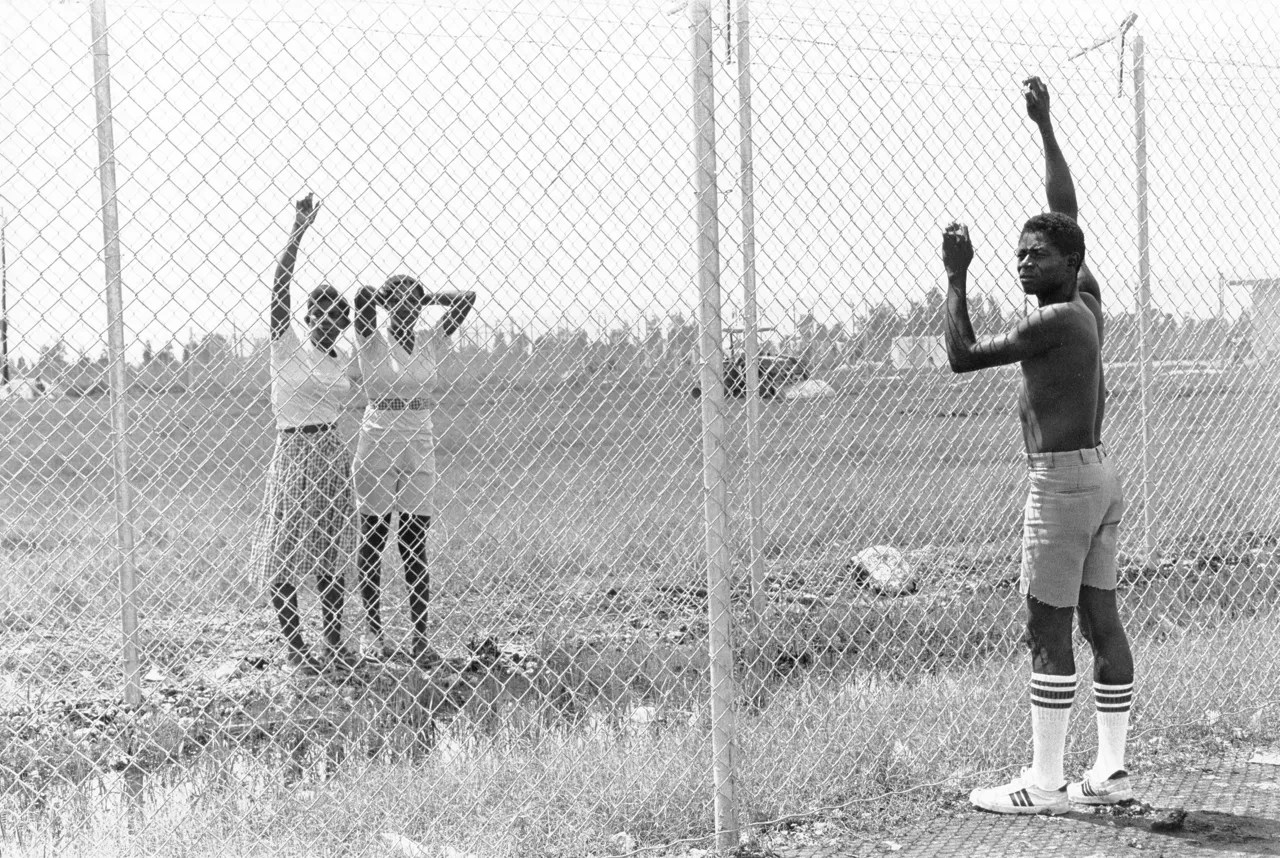

A man and two women standing on opposite sides of a fence outside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

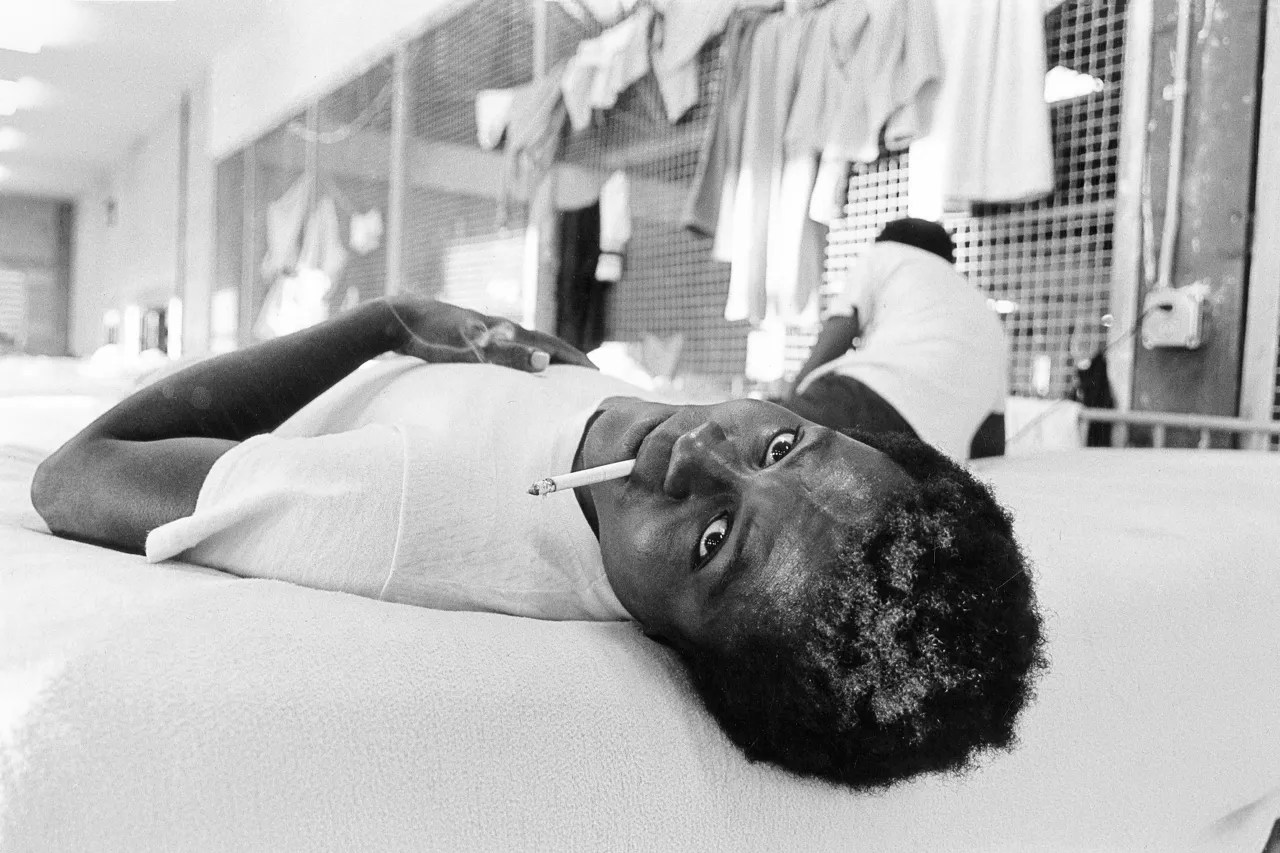

A man smoking a cigarette while lying down in the center.

Photo by Gary Monroe

Women seated inside Krome.

Photo by Gary Monroe

Women enjoying time outside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

A man resting on a bed inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

A man smoking a cigarette while seated inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe

Men hanging around a fence outside Krome.

Photo by Gary Monroe

A detainee wears a shower cap inside the facility.

Photo by Gary Monroe