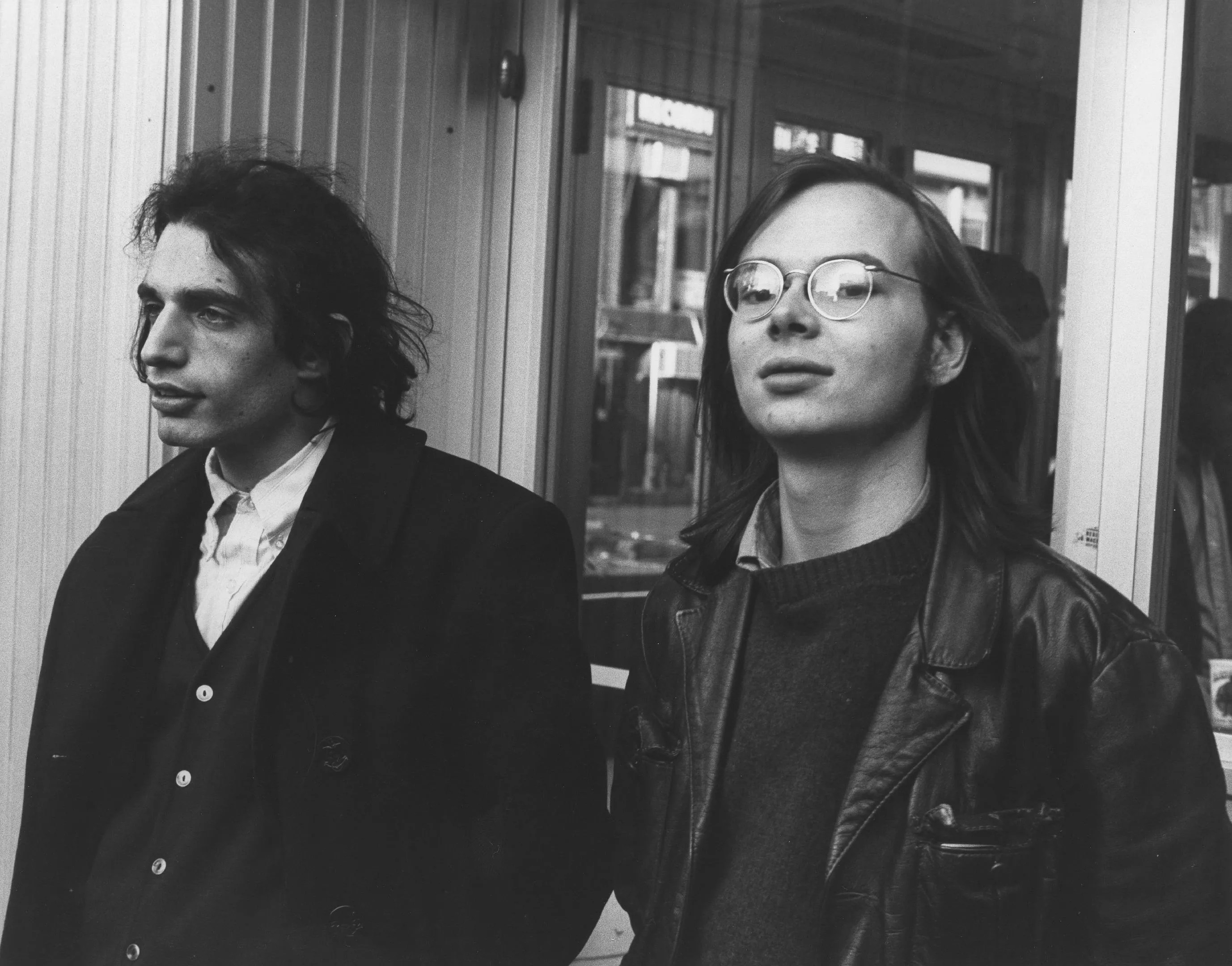

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

The last time I went to karaoke with friends, the first song anyone picked out wasn’t by Frank Ocean, Beyoncé, or any supposed generational icon for Millennials. No, my 30-year-old friend – let’s call her Josie – strode up to the mic and gave her rendition of “Deacon Blues” from Steely Dan’s iconic 1977 album Aja, a record my 60-something parents own on both CD and vinyl.

Josie is not alone in appreciating “the Dan,” as some people like to call the band. Millennials and Gen Z have embraced the music of Walter Becker, Donald Fagen, and a small army of session musicians. The internet is replete with Steely Dan meme accounts – one of the most high-profile, Good Steely Dan Takes (@baddantakes) on X, formerly known as Twitter, was even profiled by Rolling Stone.

Publications from the Los Angeles Times to the Ringer have wondered aloud about the phenomenon of twenty and thirty-somethings embracing their parents’ – hell, maybe even their grandparents’ – music. Alex Pappademas of the LA Times correctly pointed out that the trend started long ago, with the 2005 web series Yacht Rock parodying and mythologizing the group and their “feud” with the Eagles. (Ironically, Steely Dan is opening for the Eagles on their farewell tour, arriving at the Hard Rock Live on Friday, March 1, and Saturday, March 2.) When Becker died in 2017, tributes came in from Millennial musical luminaries: Questlove, Mac DeMarco, Jason Isbell, and others. And as another anecdotal example, a one-time buddy of mine owned a pair of well-worn Aja-themed sweatpants that he adored.

There is certainly something in the band’s career arc that anyone under 40, let alone a musician class mostly impoverished by streaming, would envy. Becker and Fagen, two stoner types, met at Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley in 1967, bonded over a shared love of music, and eventually formed Steely Dan in 1971, naming it after a mechanical dildo from William S. Burroughs’ cult novel Naked Lunch. Pursuing a sophisticated, jazz- and funk-inflected brand of soft rock with literate, perhaps even esoteric songwriting that appealed to a generation of youth transitioning away from youthful idealism toward embittered soul-searching in the wake of the ’60s, they somehow caught the zeitgeist. After the band’s debut album, Can’t Buy a Thrill, launched two hit singles, “Do It Again” and “Reelin’ in the Years,” they went on tour and, after deciding they didn’t like it, stopped, becoming a studio band that focused almost exclusively on albums for the rest of their original run.

This is unthinkable today. Musicians make no money on their actual music anymore, largely because the market for it has been monopolized by streaming companies like Spotify that pay less than one cent per play of a single song – and, as of 2023, only if those songs reach 1,000 plays. Artists nowadays basically have to make all their money on tour, which has only gotten more expensive since the pandemic. Steely Dan, however, existed in a completely reversed musical ecosystem where the tour functioned as a promo for the record, which was what actually sold and made money. Back then, buying a vinyl record was the only way to listen to music outside of the radio.

Artists today spend so much time on the road – and posting on social media and doing other marketing- and branding-related tasks to promote their music – that they barely have time to devote to making actual music. Steely Dan, on the other hand, did nothing but make music. Their studio exploits are legendary, and their songwriting, defined by difficult chords as much as esoteric lyricism, is fawned upon by fans and critics. “What they were doing was so particular and new, it was often difficult for critics to even find a vocabulary to describe it,” wrote Pitchfork‘s Amanda Petrusich in a retrospective perfect-ten review of Aja, the band’s most iconic and best-selling record. “Steely Dan reveled in making technical choices that would have hobbled a less ambitious outfit. That they succeeded still feels like some kind of black magic.” The making of Aja’s follow-up, Gaucho, was riddled with successive crises, from difficult sessions and legal battles to Becker getting hit by a car and losing his girlfriend to an overdose. There was a drum machine named “Wendel” and an assistant engineer who accidentally erased weeks of work. Coupled with that chaos, the band’s perfectionism turned the record into an Icarus moment unrivaled in rock legend, and they broke up in 1981 after its release. These dramas are part of the band’s appeal, but the heart of the matter is that the music is just that damn good.

The Dan certainly had its detractors at the time, with Rolling Stone‘s Dave Marsh decrying the “unparalleled pretentiousness” of their later records. But they were also deeply influential. The following decade of mainstream chart music followed the band’s lead, usually taking on the same smooth-as-silk jazz-rock template and dumbing down the lyrics a tad. Kenny Loggins, Christopher Cross, Supertramp, Fleetwood Mac, and other artists of the then-called “West Coast sound” – what we now know as yacht rock – follow closely in their wake. In Japan, the soft-rock combo Sugar Babe launched the legendary Niagara label with their record Songs in 1975. It, too, is indebted to the Steely Dan sound, and it launched the careers of Tatsuro Yamashita, Taeko Ohnuki, and producer Eiichi Ohtaki, all of whom would become major voices in the sun-dappled city pop genre that defined the country’s sound in the 1970s and ’80s – and also very popular with Millennials.

Many of Steely Dan’s session musicians went on to bigger and better things. David Palmer, who sang lead on “Dirty Work,” scored a hit for Carole King with 1974’s “Jazzman.” David Paich and Jeff Pocaro, who played on Pretzel Logic and Katy Lied, would go on to form Toto. Michael McDonald – Michael fucking McDonald – performed backing vocals for the band before joining the Doobie Brothers and eventually enjoying a successful solo career.

Still, why does that influence extend 40 years into the future? There is certainly the idea that we’re caught in, as David Robertson surmised in his the Ringer article on the band, “a bitter and Manichean generational struggle, where no quarter is given, and none taken, over the power baby boomers wield as they cling to institutional power.” We listen to our parents’ music because they’re in charge, and that power also extends to control of property, jobs, and other markers of influence. Donald Fagen, interviewed in the piece, surmises something similar. Millennials, who aren’t that young anymore, are simply maturing. “As they head into middle age, a lot of kids start to forgive their parents,” he says, “so, as the prejudices of their youth crumble a bit, they’re free to be more objective about what they hear.”

But why this specific band? Why Steely Dan? The answer goes back to “Deacon Blues,” which is fundamentally about being a loser. Millennials are the unluckiest generation, the ones that have come of age through successive crises: 9/11 and the War on Terror, the Great Recession, the Trump presidency, and the pandemic and its resultant inflationary economy. It’s been dealt with a shoddy, volatile, deregulated economy, and many will likely never own a home because their parents’ generation continues to cling, dragon-like, to their accumulated wealth. Zoomers are probably even worse off, dealing with the stresses of all that, plus an alienating social fabric informed by having to be online all the time. Oh, and climate change is a thing, lest we forget.

When Millennials hear something like “Deacon Blues,” they hear themselves being described. They are the ones likely to “die behind the wheel” and “crawl like a viper/through these suburban streets” because they live in the car-dominated landscape the boomers built and sustained. They live in the afterglow of failed social movements like the Bernie Sanders campaign, just as Becker and Fagen watched the counterculture fall apart in the early ’70s. This is no longer the “age of the expanding man.” For Millennials, things have consistently contracted, crumbled, and gotten worse. They can’t live out their dreams like their parents did.

So let’s all listen to some smooth rock and call ourselves “Deacon Blues,” and maybe we’ll feel better.

The Eagles. With Steely Dan. 7:30 p.m. Friday, March 1, and Saturday, March 2, at Hard Rock Live, Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino Hollywood, 1 Seminole Way, Davie; 954-797-5531; seminolehardrockhollywood.com. Sold out.