Photo courtesy of Speedy Legs

Audio By Carbonatix

It was the fall of 1982, and Gus “TK” Rodriguez had just scored $150 at a talent show. Since arriving from New York to study at the University of Miami, he’d been slipping out of Coral Gables every week to earn some extra cash around town.

TK was a rapper, and he believed no one in Miami had the talent to beat him. That is, until one night when he showed up to Casanova’s Wednesday night talent contest in Hialeah. While TK waited to take the stage, a clean-cut, preppy-looking guy who couldn’t have been taller than 5-foot-8 walked through the door and handed the DJ a promo record. At the opening beats of Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” the guy strutted to the dance floor and began to uprock in the center, crossing one foot in front of the other. Shifting his weight and shuffling between both feet, he moved side to side to the beat before dropping to the floor on the palm of his hand, twisting and turning in rotation. Then, he lowered his shoulders to the ground, scissored his legs to get momentum, and spun on his back, stopping in a freeze on the crown of his head.

He called himself Oz Rock.

TK remembers going up to him that night and introducing himself: “I say, ‘You want to go make some money?’ And Oz said, ‘Yeah, let’s go make some money.'”

Immediately after, TK called his friend, Mohamed Moretta, who was DJ’ing at a club in Kendall.

“I said, ‘I got a little bit of a show for you people,'” TK recalls. Moretta told them to come on over. TK and Oz Rock headed to the club and hit the dance floor. Oz Rock danced. TK rapped. The crowd went crazy.

As they were leaving, TK pulled Oz aside. “You know,” TK said, “we can do this every weekend together.”

“I saw the dude I had met, flipping around on one hand off his shoulder and his neck.”

Around the same time, Ricky “Speedy Legs” Fernandez was working out one afternoon behind Hialeah-Miami Lakes High School, a few blocks from the Hoffman Gardens public housing projects where he grew up. A karate student and fan of Bruce Lee, he was practicing his moves and trying to channel the Dragon’s intensity when he was interrupted by a stranger who sported an afro and wore jean shorts and a cut-off sweatshirt with a Playboy bunny in the middle.

“I thought he was cool looking,” he remembers. “I knew he wasn’t from my neighborhood.”

The two talked for a while, mostly about their mutual admiration for Bruce Lee. Speedy Legs didn’t expect to see the guy again, but a week later at a junior varsity football game, he recognized him in the middle of a crowd in the parking lot.

“I saw the dude I had met, flipping around on one hand off his shoulder and his neck,” Speedy Legs says today. “That was my first introduction to Flex. It was my introduction to breaking.”

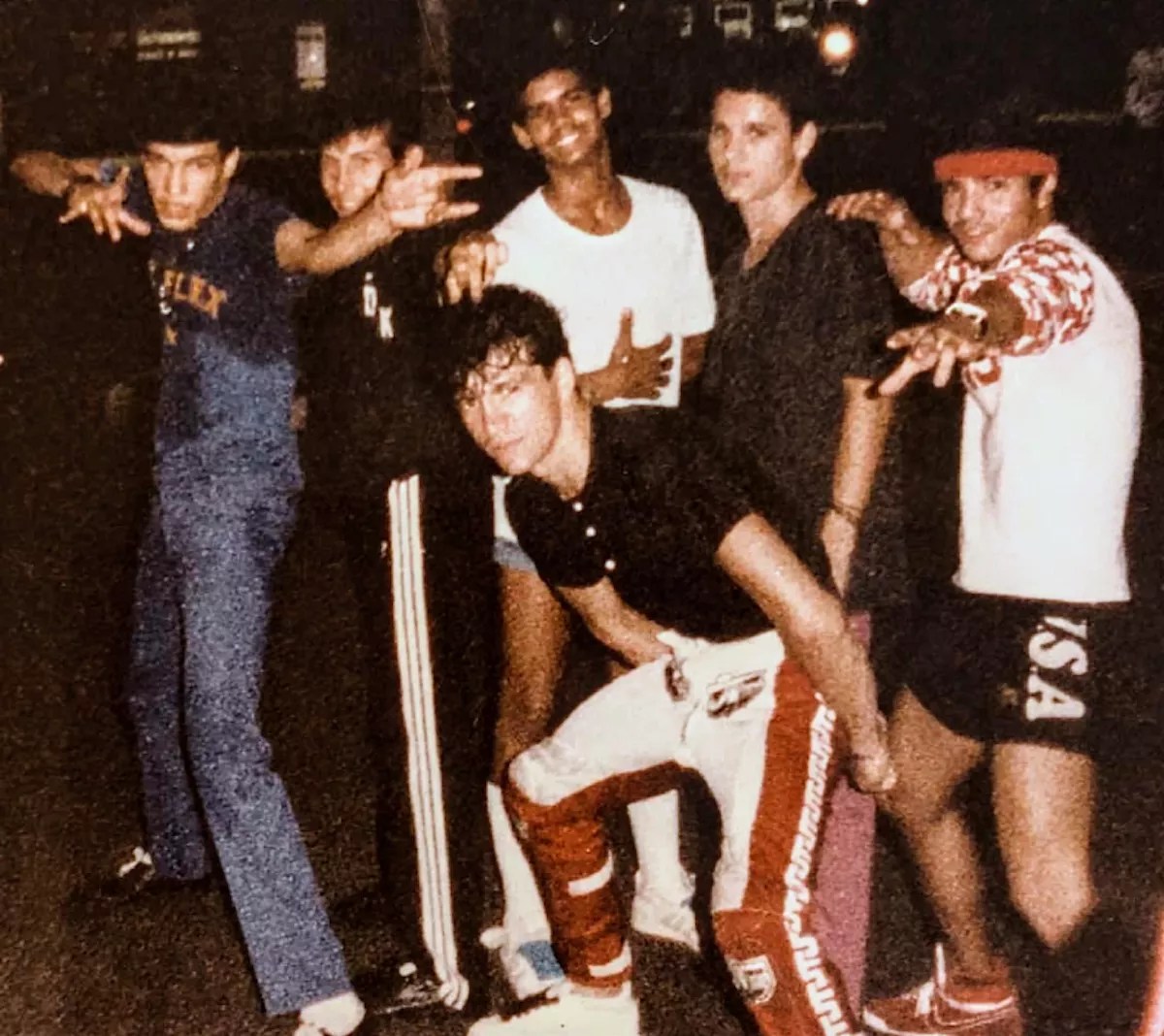

Flex (top right) and Ricky “Speedy Legs” Fernandez (bottom) met while Fernandez was a student at Hialeah-Miami Lakes High School.

Photo courtesy of Speedy Legs

Before the B-Boys

In the 1970s, youth gangs in New York who saw their rivals at nightclubs would line up across each other to fight. But DJs like Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash wouldn’t stand for it, so instead, gang members took turns one-upping each other with devastating dance moves. In a demonstration of acrobatic strength and with turf-war bravado, they battled their rivals during the extended breaks on old funk records.

The term b-boy, for break boys or beat boys, was born, and a street culture that incorporated break dancing, graffiti, rapping emcees, and turntable DJ’ing would soon take off.

In Miami, before Oz Rock and Flex, there was no breaking. Dancing followed either traditional Caribbean and Latin styles or contemporary American disco. Maybe someone popped off a few robotic moves on the dance floor at the Mutiny to impress friends, but there were no battles. Before Oz Rock and Flex, there were no b-boys.

Like all b-boy stories, this one originates in New York.

Oz Rock was born as Adolfo Alvarez in 1964 in Queens. His parents, Jorge and Hilda, had emigrated from Cuba four years earlier. In 1976, the couple divorced, and Oz Rock went to live with his father in Providence, Rhode Island; his younger sister, Neifa, stayed with their mother.

Jorge was an educator who worked as a high-school principal in Providence. Oz Rock didn’t care much about academics, which often led to fights at home. A born performer, he would bring his boombox to school and start busting moves for an audience of classmates, a sort of tacit middle finger to his father down the hall.

“Oz didn’t give a shit. He thought he was invincible. He defied his father,” says Adolfo “AD” Peralta, who met Oz Rock in the ninth grade and later joined him as member of the Top Master Crew, one of Rhode Island’s original b-boy crews.

After high school, Oz Rock returned to New York, taking up residence anywhere he could find.

“One of the nicknames we had for Ozzie was Pedestrian Head,” TK recalls. “Ozzie could show up in any city and he’d find a comfortable sidewalk to sleep on. Ozzie was always on somebody’s couch. That’s kinda how Oz existed for almost the entire time that I knew him. Literally, he was the ultimate house guest.”

In Miami, before Oz Rock and Flex, there was no breaking. Before Oz Rock and Flex, there were no b-boys.

During that time, Oz Rock approached Dynamic Rockers, the top b-boy crew in Queens. Victor “Glyde” Alicea, the crew’s leader, remembers it well.

“He’s telling me, ‘Yo, Glyde, I’ve heard a lot about you. I want to get with you guys. Just give me an audition here, let me try.'”

Oz quickly proved himself and won over Glyde.

“He became part of Dynamic. He was with me for maybe a year,” Glyde says.

Like Oz Rock, Flex’s family hailed from Cuba. Flex was born José Manuel Montells-Soto in Havana one year after Oz. His family moved to the U.S. when he was a young boy, first settling in 1970 in the South Bronx, considered by many as the birthplace of hip-hop. Later, the family moved into an apartment in Manhattan across the University Heights Bridge. Flex says guys came from Queens and the Bronx to hang out there, including some of the most famous b-boys – Kid Nice, Fast Break, Chino, Be-Bop, Glide Master. The building became their playground. They called themselves the Floor Masters.

“We used to practice in the lobby area, getting off on each other’s moves,” recalls Richard “Fast Break” Williams, who later became a member of the Magnificent Force crew, which was featured in the hit film Beat Street.

In January 1982, the Floor Masters were invited to Club Negril, a reggae club in the East Village, to take on the Bronx’s Rock Steady Crew in the club’s first battle between b-boys. It was organized by Michael Holman, a promoter and occasional culture writer for the East Village Eye magazine who first coined the term hip-hop. He was blown away.

“I witnessed the Floor Masters and I witnessed power-breaking for the first time, and I was like, ‘Oh shit,'” he says today.

Holman later poached four members of the Floor Masters to form an all-star crew, although Flex didn’t make the cut. The New York City Breakers would become one of the most famous crews in b-boy history, at one point even performing for President Ronald Reagan.

While Flex was battling with the Floor Masters, Oz Rock was perfecting his b-boy moves with the Dynamic Rockers. “He learned a lot of our drills, all the basics,” Glyde says. “You know, footwork, windmills, back spins, swipes – all the basics. Chairs, and all that, he learned that from us.”

It was during one of those sessions that Flex and Oz Rock first met. Flex happened upon the training center in Queens where Oz’s group was practicing.

“He was with the Dynamic Rockers,” Flex remembers. “They were actually training, like real training that you can get on a blue mattress and throw your body upside down and not be afraid to break your neck.”

Flex describes his immediate connection with Oz Rock in an almost mystical manner. “That type of understanding and connection, it comes actually towards the neighborhood, from a beginning that grows that part of the fundamental construction of dirt,” he says. It felt like they were made of the same DNA. There was a grittiness to Oz Rock that he instantly vibed with.

Although they ran with separate crews, Flex says he and Oz Rock became like brothers. “He knew something,” Flex says. “The guy was out there, in the street. The word ‘survival’ – I think that is the right word. He knew how to survive, bro.”

In the summer of 1982, after Flex’s grandmother passed away, his mother decided to relocate the family to South Florida, and they settled in Hialeah. His sister, Maria Diaz, says the move was difficult for Flex.

“He came over here and was in a world here that had nothing to do with break dancing,” she says.

Coincidentally, Oz Rock began traveling to Florida to spend time with his grandmother, who lived in Hollywood. Flex and Oz Rock soon ran into each other again at a Hialeah skating rink.

Flex was roller-skating with the crowd, feeling the music, when a circle of people started to form in the middle of the rink. He saw a figure in the center with white gloves and glasses popping some dance moves. Recalling the block parties in New York, Flex traded his skates for his sneakers and returned to the rink to join in.

“I see the guy breaking it down and then he’s spinning [on his back]. When the guy comes up again, I say, ‘Oh snap, it’s Oz Rock.’ It was like that kind of coincidence,” Flex says.

That night, the two New York b-boys went head-to-head for the first time on the rink. “It was phenomenal,” Flex remembers. “The people loved it.”

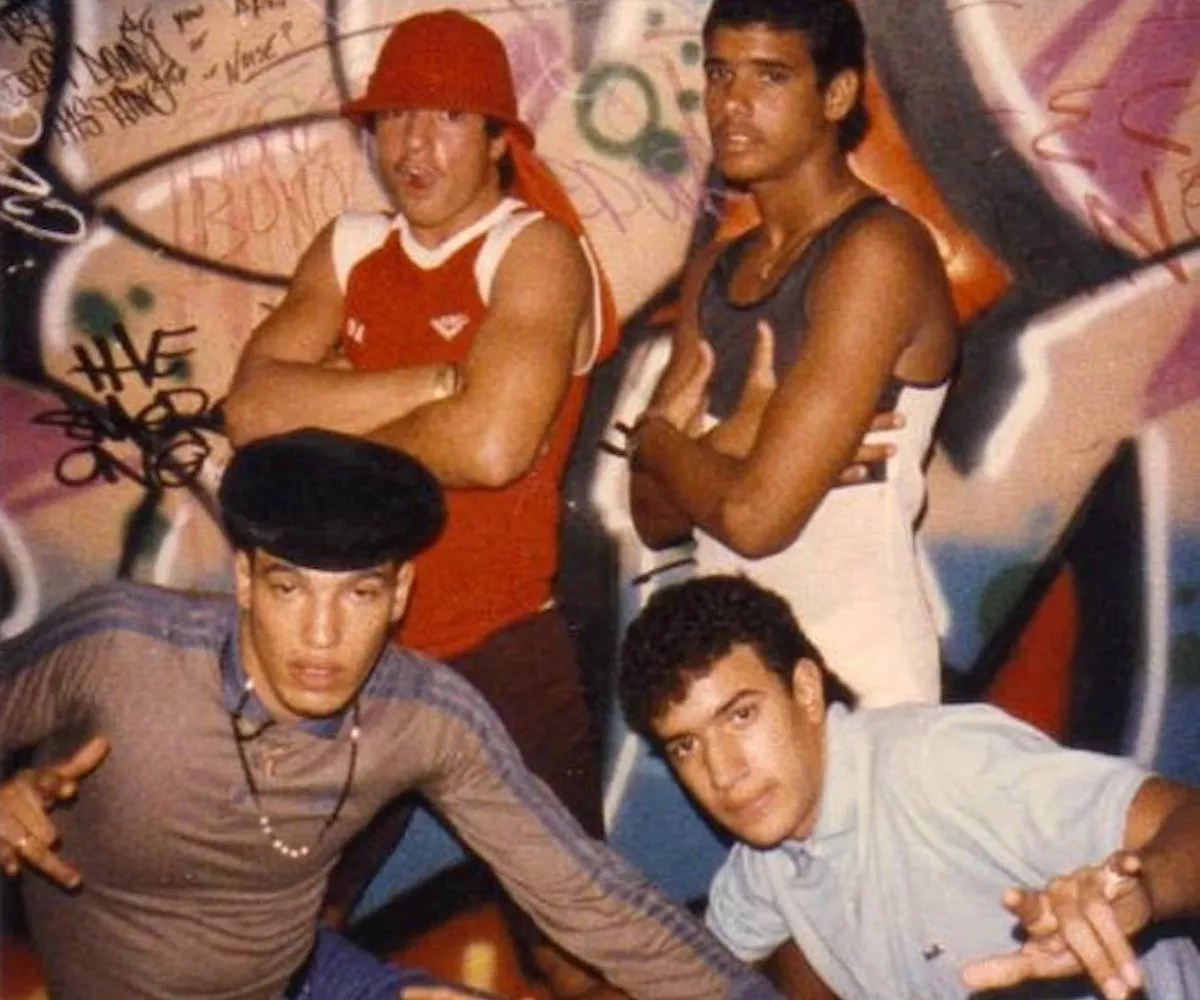

Flex (bottom left) frequented venues like the Beat Club, a favorite among b-boys.

Photo courtesy of Speedy Legs

Sensing an opportunity, the duo began hitting clubs around Miami on the weekends to enter dance contests. A buzz started to spread. Local kids began paying attention to the new b-boy culture emerging and gravitated toward the dance circles forming at roller-skating rinks and house parties.

Other New York b-boys soon followed Flex and Oz Rock to Miami. A new arcade called the Video Powerhouse became one of their go-to spots.

“That was where the New York crowd went,” says Speedy Legs. “Rarely anybody from Miami would go there. Even the music they played was different.”

Video Powerhouse boasted 100 arcade games, remote-control race cars, and a disco for teens. But the Coral Way venue was best known for the New York b-boy scene it fostered.

“All those guys had a particular flavor. We just knew they weren’t from Miami,” says Willie “Almighty Chill Ski” Perez, a Miami b-boy. “They had a little bit of something about them. We used to call those guys the New York Heads.”

Elsewhere, corporate America saw potential in the new street culture. Adidas gained traction with East Coast b-boys and rappers due in large part to the popularity of Run-DMC. When Nike wanted a piece of the fast-growing market, the company held dance trials in New York to recruit talent for upcoming trade shows to hawk a new line of street apparel. Oz Rock auditioned and was selected. He was sponsored by Nike and relocated to California, where he became an early influencer, wearing Nike streetwear around L.A. He invited his friends to join him. TK made the move out west. So did Flex.

“Ozzie’s grandmother paid for my brother’s trip to California,” says Diaz, Flex’s sister.

Oz Rock (second from the left) was sponsored by Nike and relocated to California, where he became an early influencer.

Photo courtesy of Peaches Rodriguez

In just a few months in California, Oz Rock’s stock grew. Between 1983 and 1984, he danced in a Mountain Dew commercial, performed on Solid Gold and The Merv Griffin Show, acted in a ZZ Top music video, appeared in an after-school special with Mr. T, and stunt-doubled a backspin for Judd Nelson in a motion picture. At night, he rubbed elbows with artists and entertainers including Ice-T, Chaka Khan, Pauly Shore, and Todd Bridges.

“The opportunities Hollywood started to see was that there was money to be made and it was becoming more popular, so now they’re [introducing] poppers and breakers into music videos and things like that. And then the movie offers came,” recalls Robert “Ace Rock” Aceves, an L.A. popper who appeared in the film Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo.

Oz Rock landed a speaking part in the film Body Rock. Flex appeared in two scenes, although he wasn’t mentioned in the closing credits.

Following the success of earlier breaking films like Beat Street, Breakin’, and Breakin 2, a film crew began scouting locations in Miami. Originally titled Cry of the City, the movie was to feature a new dance crew from Miami known as the Street Masters and include b-boy battles on the streets. Flex recorded the theme song for the film, a hip-hop track called “Rockin’ It” that featured the FBI Crew, a Miami b-boy crew.

“That was supposed to be the biggest breaking movie to date,” says Speedy Legs.

But the film was delayed for two years after news surfaced that one of the film’s producers was Michael Franzese, a mobster and top earner for the Colombo crime family.

“They actually cut out Sammy Davis Jr. from the film because of the scandal,” says Joe Granda, who managed Video Powerhouse and produced the film’s theme song with Flex. “There were a lot of big-name artists involved in the movie that also exited with their songs and soundtrack.”

The film was released as Knights of the City. “When the movie came out, it wasn’t a breaking movie. It was a gang movie. So the movie was a flop,” says Speedy Legs.

Oz Rock landed a speaking part in the 1984 film Body Rock.

Courtesy of New World Pictures

Breaking Goes Bust

In 1984, Oz Rock jumped at an opportunity to be part of a dance tour in Asia, and Flex joined him. During a stop in the Philippines, Oz Rock met a young Filipino woman who worked at a hair salon and married her that December. After the tour, both Oz Rock and Flex returned to Miami. Oz Rock settled with his wife, who was pregnant with their son. But the spotlight was fading.

“By 1985, breaking was already extinct,” Speedy Legs says today. “The only people in New York that were left, they were hustling, selling drugs, you know. Nobody was really doing anything.”

In Miami, b-boy favorite venues like Video Powerhouse and the Beat Club closed. With no real future in breaking, Oz Rock hooked up with former crew members from New York and developed a cocaine habit.

He was arrested and spent the next two decades in and out of prison. During a rehab stint in a Florida detention facility, he tried to escape, stealing a vehicle van and almost killing a security guard. In March 1989, he was charged with attempted first-degree murder and sentenced to 20 years.

Flex also fell into drinking and drugs and sometimes ended up sleeping on the streets. He did dance gigs at any nightclub that showed interest and worked odd jobs, shucking pallets at a computer warehouse and bussing tables at a Red Lobster. He says he never made more than $5 an hour. Like Oz, he also had trouble with the law, getting arrested for disorderly conduct, loitering, petty theft, and marijuana possession.

In Miami, before Oz Rock and Flex, there was no breaking. Before Oz Rock and Flex, there were no b-boys.

In 1999, Flex uprooted his entire life and moved to Germany with his wife. He left so suddenly that he didn’t even tell his family. “I saw in Hialeah, brother, that there was no hope for me no more. I fell hard into drugs. The way that I was going, I had to get out,” he says now. “My own mother said I was killing myself.”

For a few years, Oz Rock wrote letters from prison to Flex, Speedy Legs, and other friends. Ace Rock, the guy from Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, remembers some of the letters. “He was hurt and upset that the scene had moved on a little bit… We’re both part of this movement that happened. And now the movement moved on without us.”

In 2010, during an altercation with another inmate, Oz Rock was thrown over a second-floor rail and became paralyzed. He suffered kidney failure and died in May of that year.

Flex has never returned to Miami. He lives in a town of 10,000 residents east of Cologne and spends most days and nights scouring the internet for images and videos of b-boys and hip-hop culture, which he endlessly archives. Now 55, he still harbors regrets that date back almost 40 years.

In 1999, Flex uprooted his entire life and moved to Germany with his wife.

Photo courtesy of Flex

“If I would have stayed in New York, I would have probably been in the movie Beat Street, as well as in the Magnificent Force [crew],” he says, “or I probably would have been in [the 1983 b-boy cult classic] Wild Style.”

His sister worries he’s not well. “His mind is stuck in the past,” she says.

While Flex and Oz Rock never gained much lasting notoriety, the trail they blazed in Miami in the early 1980s was important groundwork for the future of breaking, Speedy Legs says. In 2024, for instance, breaking will be an Olympic sport in the summer games in Paris.

Speedy Legs himself thanks Flex and Oz for his career. In 1997, he launched the Miami Pro-AM expo to give breakers a more official platform to compete. The event is still going strong – in June, Speedy Legs and his business partner, DJ Felix Sama, hosted members of the New York City Breakers, Rock Steady Crew, and Dynamic Rockers at the Pro-AM Dance/DJ Expo at the Miami Airport Convention Center.

“If it wasn’t for those two guys, there would’ve never have been a Speedy Legs. There would have never been a Pro-AM, which became the blueprint for professional and amateur breakdancing competitions, which is now an Olympic sport,” Speedy Legs says. “It was Oz Rock and Flex that made the scene in Miami because they were ahead of everybody else.”

Flex doesn’t seem to pause and reflect much on his contribution to the hip-hop scene at large. He doesn’t come to the Pro-AM, and he’s lost contact with many of his former friends. He’s also stopped breaking – years of hard living have left him physically unable to bust the incredible backspins he was known for.

But that hasn’t prevented him from putting in other work, such as slinging mic-dropping rhymes. I’m on it, on it, to the beat, he freestyled on a recent recording.

When asked what he means, the street-wise Flex says without hesitation: “I’m on to something.”

“You have to keep going,” he says, “keep struggling, keep surviving.”