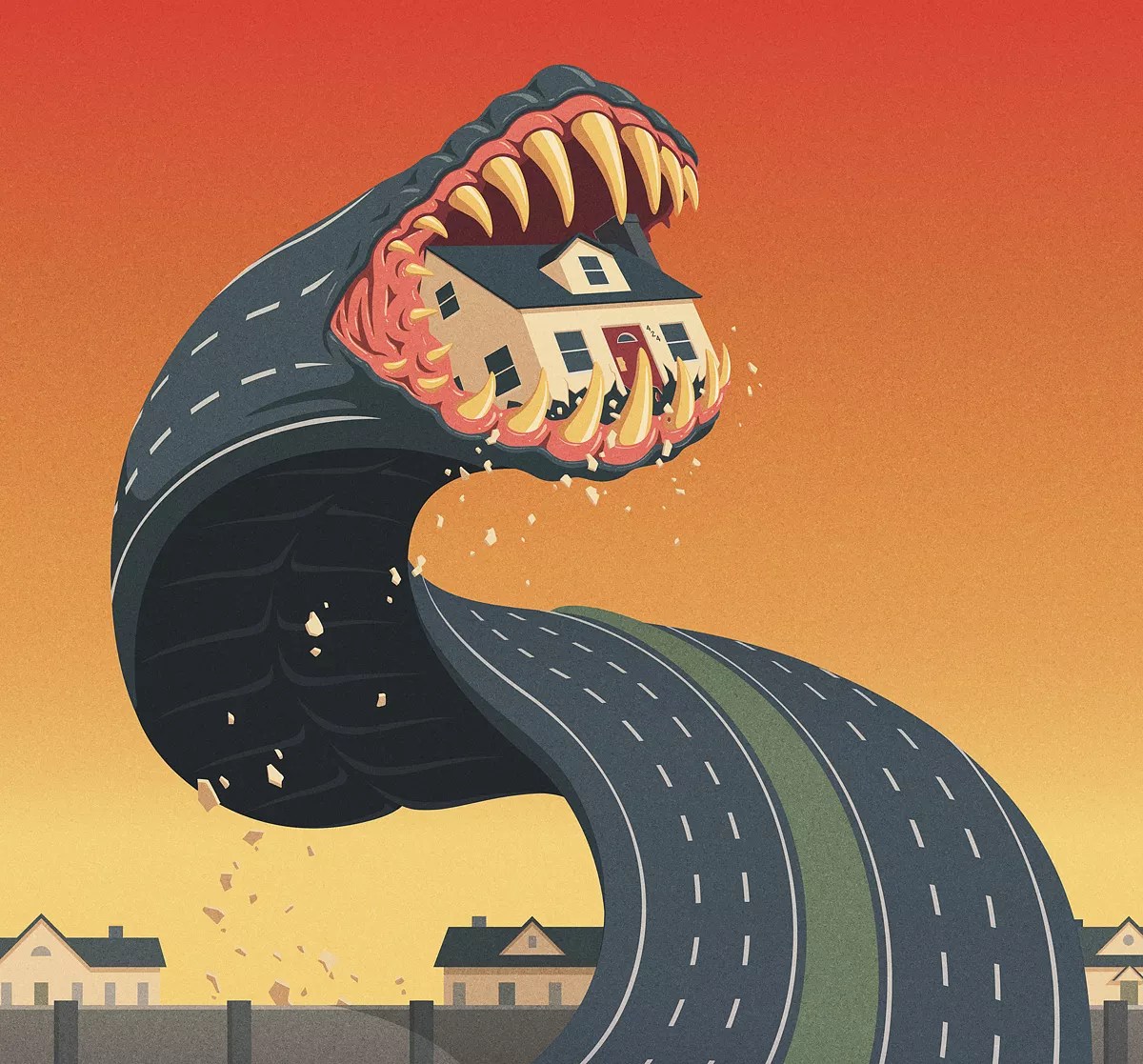

Illustration by Chris Whetzel

Audio By Carbonatix

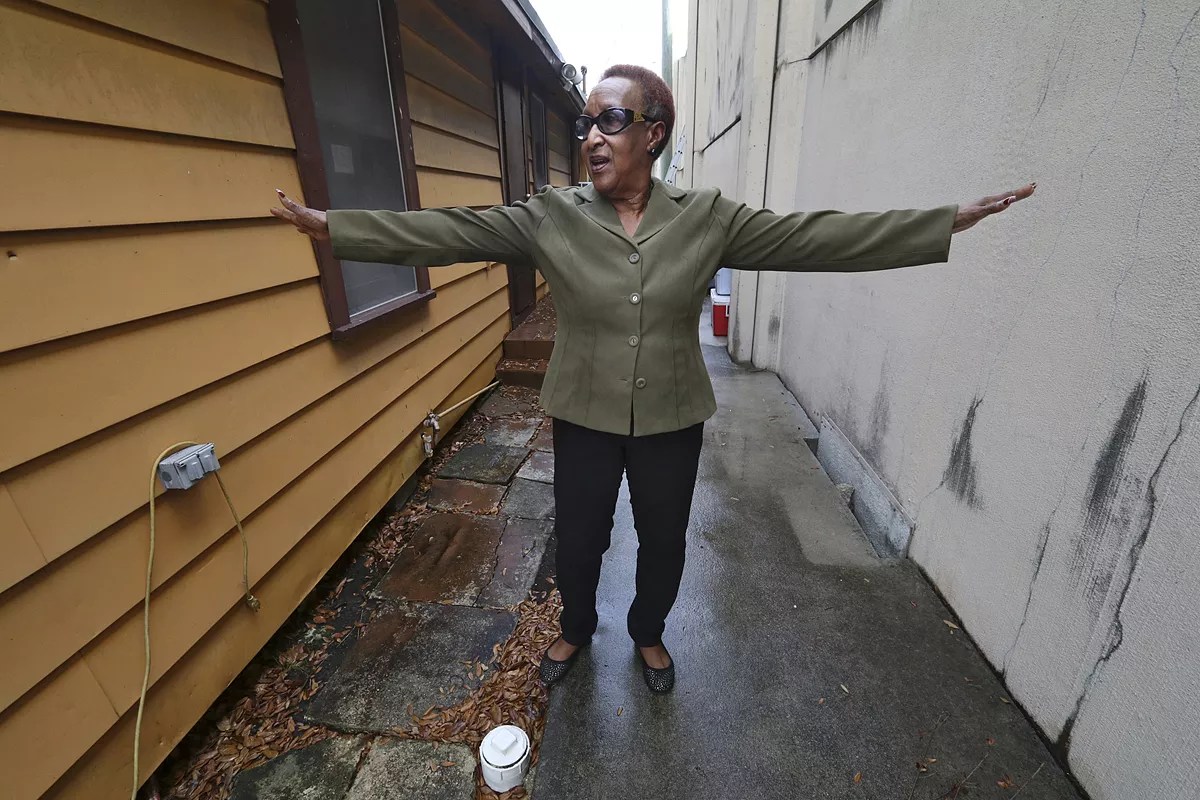

Sybel W. Lee stomps her foot on the vinyl floor in her kitchen. On the wall hangs a sign: Love makes a house a home. But the truth is, this house stopped feeling like a home a long time ago.

Lee moves to another spot a couple of feet away and bounces on top of it.

“It’s weak right here,” she says before pointing to the edge of her cabinets. “Oh, and that’s the rat infestation I had right there. That’s what that bite mark there is about.”

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

Lee’s three-bedroom home on NW 100th Street, just west of Miami Shores, hasn’t been the same since the state expanded I-95 into her backyard in the early ’90s. The ground shifted, which disrupted her home’s foundation and stirred up nearby rodent colonies. Polluted air leaked in and made the whole place smell like a gas station. Occasionally, cars flew off the road and through the flimsy chain-link fence separating the busiest highway in America from her neighborhood.

But the state’s solution to the problem actually made her living situation even worse. In 2001, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) erected a 20-foot-tall concrete barrier just six feet from Lee’s back door — almost close enough for her to reach out and touch. The wall’s construction damaged her septic system so badly she could no longer flush toilet paper. Terrified that an 18-wheeler would smash through the barrier and into her home, she stopped cooking at her stove and strategically timed her showers around rush hour, because her kitchen and bathroom are the closest rooms to the interstate.

“This project here, I call it the I-95 Nightmare,” says Lee, a 73-year-old adult educator with short cropped hair and chunky brown eyeglasses. “My whole life has adapted to their inconvenience on me.”

“This would have never been an issue had they done what they said.”

Worst of all, Lee was supposed to have moved to a quieter neighborhood years ago. In 2002, Lee says, the county agreed to buy her property and the properties of two neighbors, Mary Anne McMinn and Nathaniel Williams, so they could be relocated to safer housing. But for some reason, that never happened.

More than 15 years later, next to a highway carrying 325,000 vehicles per day, the seniors are still living in crumbling homes where they breathe noxious fumes and shell out $1,300 every time their plumbing gets backed up. All three have suffered from chronic health problems they attribute to the interstate, including blackouts, difficulty breathing, and blurred vision.

“We’re suffering in our golden years,” Lee says. “This would have never been an issue had they done what they said. They just absolutely took advantage of us.”

A New Times review of county records and emails shows exactly what a raw deal the homeowners got: After repeatedly promising to relocate the seniors, county officials instead used the money — nearly $800,000 — to beautify the Venetian Causeway and teach a class on pedestrian safety.

In a last-ditch attempt to escape the superhighway running through their backyards, Lee, McMinn, and Williams have filed a federal lawsuit against Miami-Dade County and FDOT. Although it’s been years since the original negotiation, the homeowners are unwilling to compromise on what they were promised — cash payments for the 2003 values of their properties, plus the full cost of relocation and damages.

But most of all, they simply want someone to be held accountable for their years of suffering.

“They’re waiting for us to die off,” Lee says. “They think they’re gonna get away, but I’m not gonna let them get away. I don’t care if it takes until I die.” After expanding I-95 in the ’90s, the state built a noise barrier wall just six feet from Sybel W. Lee’s house. Photo by Kristin Bjørnsen

Lee was 3 years old when her parents — a nurse and a truck driver — moved from North Carolina to Florida to be closer to

“We moved from there to Brownsville,” she says. “It interrupted my whole school life.”

From the ’20s through the ’50s, Overtown was a thriving community of black nightclubs, theaters, restaurants, and churches. But after Florida plowed a highway straight through the neighborhood, Overtown was never the same.

At first, the state proposed running the interstate alongside the Florida East Coast Railway tracks into downtown Miami, a route through an industrial area that would have had little impact on housing. Instead, historian Marvin Dunn says, downtown business owners and the Chamber of Commerce pushed to move the expressway west into Overtown. By the time construction on the stretch between Fort Lauderdale and Miami was complete, an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 people in the mostly black neighborhood had been displaced.

“The decision to run the interstate through the black community was deliberate, intended to displace a large segment of the black population so that the valuable land on which Colored Town sat could be used to expand the downtown business district,” Dunn writes in his 1997 book, Black Miami in the Twentieth Century.

After Lee and her family were forced out of their home, her life changed dramatically. To catch the bus from her new neighborhood, she woke at 5:30 each morning and had to walk home after school. In the 11th grade, she says, she dropped out after an older man she met on that after-school walk took advantage of her and she became pregnant.

“This road has followed me from my youth,” she says. “And this road from hell continues to damage my life.”

After earning her GED in the ’70s, Lee landed a job as a reservation agent for Eastern Air Lines and began taking college courses to pursue a career in education. She raised her young children in Liberty City until the mid-’80s, when rising crime forced her out.

“I had three daughters then,” she says, “so I didn’t want the environment that I saw arising.”

“This road from hell continues to damage my life.”

In 1985, Lee found the perfect country-style home at the corner of NW 100th Street and Sixth Avenue. The owners, a sweet elderly couple who had lived there for decades, told her they’d been holding out for someone just like her, a person who would love their home and take good care of it. Lee bought the house for $35,000 and quickly settled in. At the time, the interstate wasn’t close enough to concern her.

“It was way out there,” she says. “The backyard was nothing but bushes.”

Not long after moving, Lee met her next-door neighbor, Mary Anne McMinn. McMinn had lived in the house since she was 11 years old; her parents bought the three-bedroom concrete home in 1955, just a few years before I-95 was built.

“We didn’t know anything about no road coming through here in ’55,” says McMinn, now 74. “My dad just picked the house and said he liked it.”

McMinn’s first real beef with the interstate came in 1979, when a car ripped through the back fence, hit her truck, and overturned, just barely missing some gas cans piled in the backyard. She was tormented by the thought that only a few inches separated her family from a massive explosion.

“For a while, I was kinda numb and didn’t know what to do,” McMinn says. “I took it upon myself to start writing letters to all kinds of senators and governors.”

Almost always, McMinn’s letters went unanswered. Life in the racially diverse, working-class community went on as usual — horns honking, fumes floating, cars flipping. But the interstate forced the neighbors to come together. At community meetings, they begged the state for a barrier to protect them from noise pollution and crashes. In 2000, they formed the group Neighborhoods in Action.

Lee and McMinn met Nathaniel Williams at one of the organization’s first meetings.

“Had I been there that time, it would have killed me,” the 85-year-old Army veteran says.

Together, the neighbors became a force for change. They knocked on dozens of doors, rallied local politicians, and badgered the state to release a study about traffic noise. The group’s first real success came in

After the construction was finished, though, the neighbors realized their problems were far from solved. Although the wall blocked a significant portion of the noise, it was erected dangerously close to several homes. Lee and McMinn enlisted the help of state Rep. Philip Brutus, who wrote an outraged letter to FDOT on their behalf. Leroy Jones, an activist, asked Commissioner Barbara Carey-Shuler if the county might buy the houses.

In the fall of 2002, Lee, McMinn, and Williams finally got the news they’d been hoping for: Carey-Shuler told them about an FDOT grant that could pay for their homes and relocation costs. Best of all, she said the state had already transferred the funding; they should all be able to leave by January 2003.

The three homeowners never forgot that moment. The commissioner’s words still ring in their ears today: We’ve got the money. Nathaniel Williams says his house is being shaken apart by constant vibrations. Photo by Kristin Bjørnsen

At a meeting of the county’s Metropolitan Planning Organization, McMinn stepped up to a lectern and introduced herself.

“My name is Mary Anne McMinn, and I live at 601 NW 99th St.,” the bespectacled redhead said at a November 2007 meeting. “I lived there before there was an expressway, but my government has brought it into existence as a destroyer that is now so close to my home that it is no longer livable.

“I don’t consider it a home anymore,” she continued, shrugging her shoulders in exasperation. “We were promised in 2002 that our homes would be bought, but nothing has happened.”

For five years, Lee and her neighbors had waited endlessly for action, enduring an excruciating exercise in bureaucratic neglect. No one could seem to answer a simple question: What happened to their money?

After their meeting with Carey-Shuler in 2002, the homeowners assumed they would be out in no time. They contacted movers, turned over their estimates to the county, and waited for approval. January came and went, and so did February, and as the weeks and months passed, they never did get a moving date.

While they waited, the seniors’ health continued deteriorating. Lee had a hard time sleeping through the night and says the stress gave her seizures and cost her her career at the airline. Williams’ gait began feeling wobblier, and he could no longer mow his lawn. McMinn had trouble breathing, especially when she got a whiff of a strong scent like bleach.

“They kept putting us off. We looked up again — still going through sickness — and it fell through,” Lee says. “After a while, they just started giving us the runaround.”

County and state officials contacted for this story pointed the finger at each other or claimed they couldn’t remember what happened. FDOT declined to make Miami’s director of transportation development available for an interview.

But county documents obtained by New Times trace the funding from the early 2000s to present day. The records paint a picture of a neglectful government that repeatedly turned its back on three vulnerable seniors.

After the wall went up in 2001, the county planned to purchase the homes and demolish them to build a 1.5-acre linear park. Records show Miami-Dade first applied for grant funding from FDOT for the park in May 2003. Former parks and recreation director Vivian Donnell Rodriguez estimated the project would cost $1 million, with $900,000 to come from FDOT and $100,000 from a county match. Carey-Shuler also submitted a letter of support for the plan.

More than 15 years later, they’re still living in homes that are falling apart.

But the project stalled for years while FDOT and the county negotiated how much the park should cost. Then, three years into those discussions, Donnell Rodriguez abruptly pulled the plug: In a letter dated September 25, 2006, she withdrew the grant application, saying the properties were “no longer for sale.”

The homeowners say they never said their houses weren’t for sale. Lee did turn down an updated county offer because it no longer included relocation costs, but McMinn says she was still willing to sell her property at that time even under those terms. (The county contends that Williams, who lives more than a mile north of Lee and McMinn, was never part of the original agreement and therefore was ineligible to be bought out and relocated. The 85-year-old disagrees: “I was here from Day 1. Now they come and tell me I’m not included in this?”) Photo by Alex Markow

Within just a few weeks of abandoning the park idea, county leaders already had new plans for the money: Instead of purchasing the homes near I-95, the funds would be spent on a children’s pedestrian safety program and Venetian Causeway sidewalks and landscaping.

According to emails between FDOT and the county, the decision to reroute the state’s $781,000 grant was made at an October 2006 meeting with Commissioner Audrey Edmonson, who replaced Carey-Shuler on the commission earlier that year, and Jose Luis Mesa, the director of the Metropolitan Planning Organization. But when McMinn and her neighbors showed up at the county meeting in November 2007, Edmonson denied knowing what happened to the money.

“I don’t know where the funds are, nor do I have any knowledge of the funds,” Edmonson said at the time.

Today, Edmonson tells New Times she can’t recall attending the October 2006 meeting where the money was diverted. She denies siphoning funding from the park project to the other causes. “I don’t remember anything like that,” she says. “We didn’t take money from that area and send money to the Venetian Causeway.”

After the public meeting with the homeowners in 2007, FDOT and Miami-Dade attempted to revive the project and estimated it would now take $3.4 million to buy the properties and build a park. But once again, the purchases never happened. In July 2012, the three seniors appeared at another Metropolitan Planning Organization meeting.

“There’s no consideration given to the three of us, the problems that we have,” the gray-haired Williams said. “My house is ruined. There’s water in every room there is. These ladies have suffered from heat exhaustion, fumes from the cars on the expressway. I mean, that’s no way to live. And you can’t do anything? Something’s wrong someplace.”

Following the meeting, the Parks Department offered to buy Lee’s and McMinn’s properties for market value, but by then, they were worth less than half of what they had been in 2006. The two women rejected the offer — they wanted to get the value they were originally promised plus moving expenses and damages.

“I would be in debt, all the money I’ve lost patching up here and causing hardship,” Lee says. “Why didn’t they pay up when the market was up?”

Edmonson says that after the offer was rejected, there wasn’t much else she or the county could do.

“The only thing I can do is try and work again with FDOT through [the county], but I don’t know what their decision is going to be because their position is they offered the market rate and it was not accepted,” the commissioner says.

Victoria Galan, a spokesperson for the Parks Department, says the county would still consider purchasing the properties to build a new park, but only at the current appraised value.

“We’re always looking for a place to take concrete and make it green,” she says. “If that was something they wanted to bring back to the table, we definitely would look at it.” Sybel W. Lee: “This project here, I call it the I-95 Nightmare.” Photo by Kristin Bjørnsen

On a recent weekday morning, the three seniors sit on a leather sectional in Lee’s living room and dream about where they’d move if they had the money. Williams sometimes thinks about starting over in California. McMinn says she’d stay in the neighborhood but pick a home farther from the interstate. Lee would head a bit north to Port St. Lucie.

“I want out of Dade County,” she says. “It’s too

The three neighbors still don’t agree about who is most responsible for their distress, but they all point to Carey-Shuler as the first person to let them down. (The retired commissioner did not respond to phone messages from New Times.)

“She is the problem,” Lee says. “That’s why I can’t blame Ms. Edmonson, but she’s caught up in it anyway, one way or the other.”

Her statement sets off a spirited debate in the living room.

“You’re giving Edmonson a free ride here,” Williams interjects. “You’ve been lenient on Edmonson.”

“You’re taking it easy on her,” McMinn agrees. “I’ve been thinking the same thing.”

“She’s been avoiding us for a long time,” Williams continues. “She’s just as complicit in this as Shuler.”

Lee finally concedes: “She didn’t keep her word.”

“I want out of Dade County. It’s too much centralized corruption.”

This much is clear: The homeowners are in worse condition today than ever. Williams has bouts of dizziness, blurred vision, and a persistent cough he blames on the fumes. McMinn says she was finally diagnosed with reactive airway disease, a chronic condition that can be attributed to air pollution. Lee has had intermittent blackout episodes, most recently in March.

“I just came out of the hospital, four days,” she says. “I passed out in my bedroom, and when I woke up, I was on the floor.” Photo by Alex Markow

The homeowners’ lawsuit, filed in May in Miami’s federal court, accuses the county and FDOT of breach of contract and says both entities failed to rightfully compensate them. Lee, McMinn, and Williams have asked a judge for $1.2 million in damages, plus moving costs and enough money to purchase new homes. Their attorney, Matt Person, says it’s clear the county and state “dropped the ball.”

“It doesn’t pass the smell test,” he says. “It doesn’t take a scientific expert to look at the situation and say there’s something wrong with it.”

As of now, Miami-Dade hasn’t responded to the neighbors’ legal complaint. Assistant County Attorney Annery Pulgar Alfonso declined to comment on the pending litigation.

FDOT, on the other hand, has claimed it is immune from the lawsuit under federal law. It could be many months, or even

In the meantime, the three property owners wake up and go to sleep in houses that haven’t felt like homes in years.

“If I’d have known this would be the end result, I never would have purchased it,” Lee says. “We’re locked in prison in our own houses.”