Illustration by Cameron K. Lewis

Audio By Carbonatix

Valentina Villafane was sitting in her second-grade classroom when the tear gas canister exploded. The principal of her private school outside Barquisimeto, Venezuela, saw it first – an errant volley from a national guardsman that flew between the bars of the school’s gate and rolled to the front door. The principal shouted for the students to run to the back of the building as gas plumed at the entrance.

As Valentina huddled with her classmates, teachers brought jars of vinegar from the cafeteria and showed the children how to apply it to their faces to protect against the gas. They waited for hours, trapped while desperate Barquisimetanos clashed with police outside.

“I was scared and I almost cried,” Valentina recalls in a telephone interview from Venezuela.

The tear gas never reached the students, and the National Guard eventually cleared the streets. The riot erupted because the local markets had run out of food. Some residents had waited in line all day, only to receive nothing.

Now 10, Valentina has not had a brush with danger in the three years since the tear-gas incident. Her school simply closes when the risk of unrest is high. But the food shortages have worsened, and afflict all but the wealthiest Venezuelans. She is used to the sight of bare shelves, of long lines for basic goods, of people scavenging for scraps of food in dumpsters. Even children. Even from middle-class homes like hers.

“I would like to help them, but I can’t,” she says. “I feel sorry for them.”

Valentina has one advantage Venezuelans her age do not. Her father lives in the United States and is frantically trying to secure a visa so she may live with him. He was robbed at gunpoint during his last visit to Barquisimeto and fears his daughter will be struck by a stray bullet.

Venezuela, a country with abundant resources and the world’s largest oil reserves, used to be among Latin America’s wealthiest nations. Now it is on the brink of ruin. In 2013, Venezuela’s heavily regulated economy collapsed from a fatal combination of the oil bust, incompetent government and widespread corruption. Most Venezuelans can barely afford basic necessities, if they can find them at all. The government has delayed elections and President Nicolás Maduro rules, in the eyes of many, as a dictator. There is no end in sight to the crisis.

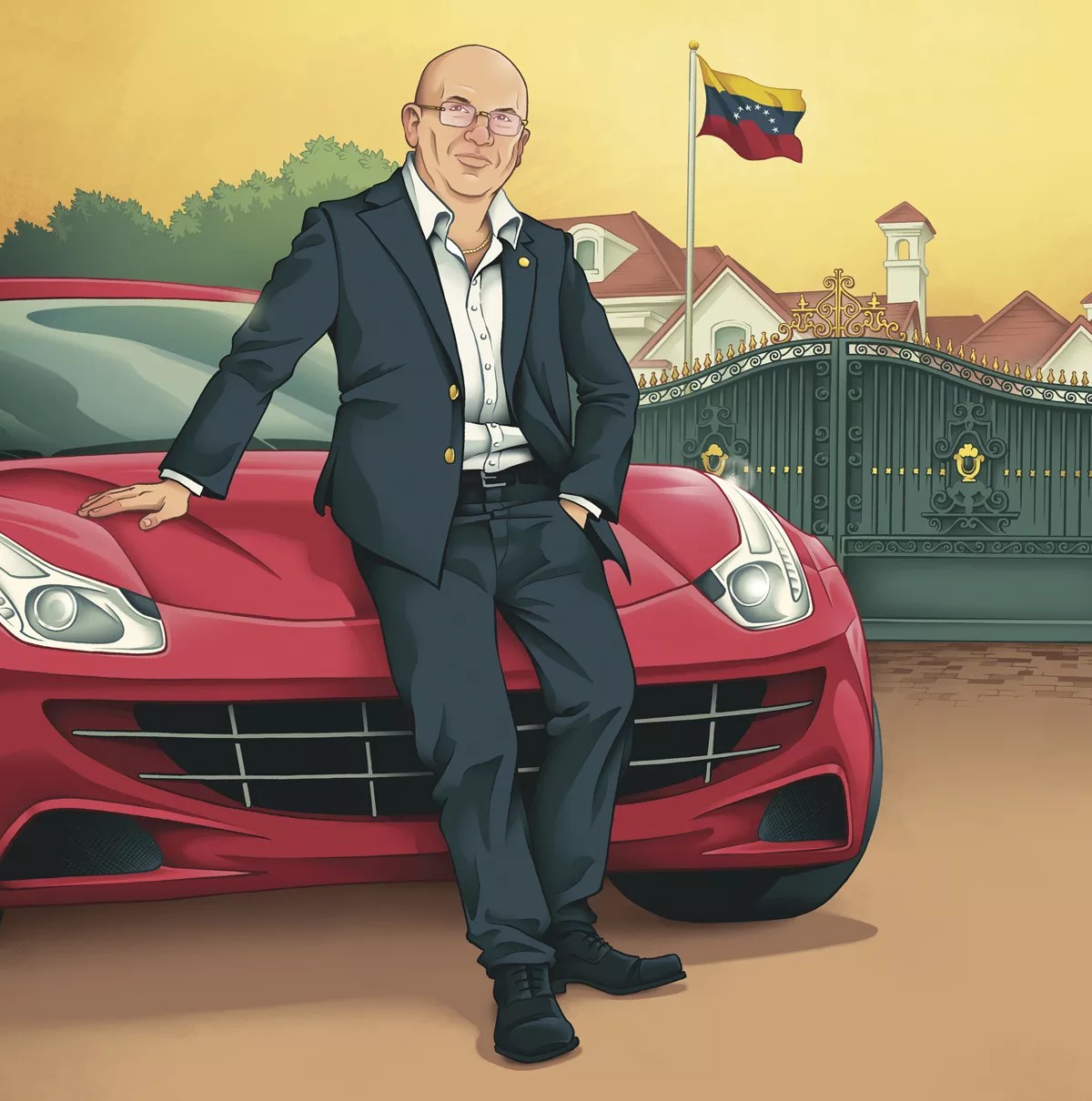

“They come here to enjoy the fruits of their ill-gotten gains.”

More than 1.5 million Venezuelans have fled into the diaspora spurred by the election of Hugo Chávez, Maduro’s predecessor, as president in 1998. Many settled in the United States, including in Houston – lured by its oil and gas jobs – and Miami, the American metropolis closest to South America. Some are poor and working-class Venezuelans in search of economic opportunity. Some are professionals who were purged by the Chávez government. And some are the same corrupt businessmen who stole billions from the Venezuelan government and plunged the country into the worst economic crisis Latin America has seen in a generation.

“They go out and they buy the most expensive house, the most exotic cars, the fastest airplanes,” says Otto Reich, a former U.S. ambassador to Venezuela. “They do it here in the United States because they’re afforded the personal security that their fellow citizens are denied in Venezuela… they come here to enjoy the fruits of their ill-gotten gains.”

Venezuelans call them boligarchs, a portmanteau of “bolívar” (Venezuela’s currency) and “oligarch.” Hundreds hide in plain sight in Venezuelan enclaves such as Weston, Florida; and Katy, Texas. These American boligarchs include Roberto Rincón and Abraham Shiera, a pair of Venezuelan businessmen who bilked their country’s state-run oil company, PDVSA (PAY-duh-veh-suh), out of $1 billion before they were caught. But billions more are missing, and American authorities are just beginning to prosecute the boligarchs here. Rincón, now the biggest fish in the government’s net, may be only a bit player in the tale of the billionaires who looted Venezuela.

Valentina is too young to remember any Venezuela but this one. She does not understand how greedy Venezuelans could make a rich country so poor so quickly, and leave families like hers to fend for themselves. Poverty doubled in two years, to more than 80 percent. And in 2015, Venezuela had nearly twice as many murders as the United States – a country ten times as populous.

Valentina’s parents had her when they were young, and divorced when she was two. Her father, JJ, moved to the United States to pursue a music degree. So she lives with her mother, stepfather, and two half siblings in a concrete apartment building next to a main highway into Barquisimeto.

Valentina distracts herself from the indignities that now fill daily life, like the lack of toilet paper that has made her country an international punch line. She protects her 8-year-old half brother from bullies. She chides her grandmother when she believes she has made a bad trade with a neighbor for scarce staples (you gave away too much toothpaste, abuela!). And she dreams of the day she will move in with her father in the United States. He lives in the Houston area.

So does Roberto Rincón.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela Otto Reich has urged stronger crackdowns on corrupt Venezuelans hiding money in the U.S.

Photo by Monica McGivern

Even the tall black gates, topped with gold, fail to hide Roberto Rincón’s mansion in the Woodlands. Rincón lives in a gated community, manned by guards, in this wealthy suburb of Houston. Second-floor curtains are drawn on this $7.1 million home, and hedges line the property. The home is expansive – visitors say it includes a garage with room for more than ten vehicles, as well as a secure panic room – and once housed many of Rincón’s family members.

A housekeeper for Rincón’s neighbors said a guard arrives at the mansion every morning around 8 a.m. and stays throughout the day. She rarely sees Rincón. But he is in there, somewhere, biding his time. He is on house arrest awaiting sentencing in July with Abraham Shiera and at least eight other defendants in one of the largest Venezeulan corruption cases prosecuted by the United States government.

Rincón, who is 56, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. He refused to let a Houston Press reporter beyond the guard post.

According to Venezuelan press accounts and motions filed by his lawyers, Rincón got into the oil business in his 20s, when he began working for an uncle in his native Zulia state, in the western part of the country. Rincón sold supplies to oil companies and in the 1980s started his own firm. Rincón was not wealthy and at one time lived in government housing built for the working class.

Then came Hugo Chávez. The charismatic ex-military officer won the presidency in 1998 and promised economic and social reform. He stocked his government with military colleagues and many allies who lacked government experience. In 2002, anti-Chávez factions known collectively as “the opposition” organized a coup and general strike, which included workers at PDVSA. Chávez regained power after two days and soon fired around 18,000 PDVSA employees – including managers, administrators and engineers – and replaced them with loyalists, many of whom knew little of the oil industry.

Rincón saw his opening. He became an approved PDVSA contractor and began bidding for lucrative contracts. Rincón moved to Houston around 2004 and, with the help of family members and associates, created a dizzying web of U.S. companies to vie for contracts.

Dozens of pages of federal court papers detail the elaborate corruption scheme. Between at least 2009 and 2014, Rincón bribed five PDVSA procurement officers living in south Texas to ensure his companies were selected. Sometimes, Rincón rigged bidding panels so that only his companies were considered for contracts.

Soon, PDVSA was paying Rincón a premium for services he never provided and goods he never delivered. But no one in the company seemed to notice. After the price of oil collapsed in 2008, and PDVSA revenues plunged, Rincón kept swindling.

In the fall of 2009, Rincón partnered with Abraham Shiera in Miami to further the scheme. Shiera had at least six companies through which he could bid for PDVSA contracts. Together, the pair found creative ways to pay bribes without arousing suspicion.

Rincón tried to hide bribe payments by sending them to family members of his PDVSA contacts, or to foreign bank accounts they controlled. In 2010, Rincón paid the remaining $165,000 mortgage balance on a PDVSA official’s Houston-area home. That same year Rincón deposited $135,000 into an account belonging to a friend of that same official. In 2011, Shiera footed the bill for a $14,502 stay at Miami’s posh Fontainebleau Hotel for a PDVSA associate. Shiera treated that same official to a hotel and a rental car in Barcelona, Venezuela, the following year. A different official got a shipment of whiskey courtesy of Shiera.

Rincón and his eldest son, José, also began to diversify the family’s holdings. In 2005, José Rincón purchased a car wash in Conroe, Texas, and founded a private security firm in 2009. The following year, José and his father formed an aviation company, Global Air Services Corp.

José Rincón has not been charged with a crime related to his father’s corruption scheme, according to sources familiar with the case.

Sources who knew the Rincóns said Roberto kept a low profile, was generous to employees and enjoyed spending time with his family in Texas, which included his mother, wife, daughter, and three sons. When Rincón’s daughter married in Houston in November 2008, they said, he hired artists from the Latin Grammys, in town for the awards ceremony at the Toyota Center, to play the reception. Months before the wedding, Rincón’s new son-in-law purchased an $843,000 home in Rincón’s gated community. Two years later, José Rincón purchased a $1.2 million mansion in the neighborhood.

For years, Roberto Rincón kept to himself and expanded his wealth. The car wash even made a $5,400 donation in 2012 to the Precinct 1 constable’s office in Montgomery County for personal flotation devices.

Shiera lived a public life out of a $1.9 million home in the Miami suburb of Coral Gables. While attending the 2012 French Open in Paris, Shiera complained to a reporter that a rain delay would cause him to miss Spaniard Rafael Nadal, whom Shiera had flown from Venezuela to see. In 2015, months before he was arrested, Shiera and his wife posed for a photograph among Miami socialites at a benefit for a Venezuelan charity that helps the poor.

Rincón, by contrast, stayed in the shadows. Those who know him described Rincón as a quiet man who trusted few people, reluctant even to be in a room with strangers. A housekeeper for Rincón’s neighbors said her employers have no relationship with him.

But a 2014 diplomatic incident brought Rincón unwelcome attention. In July of that year, Dutch authorities in Aruba arrested Hugo Carvajal, the former head of Venezuela’s military intelligence, on a U.S. arrest warrant. A federal court in New York had indicted Carvajal in 2011 on drug trafficking charges. But before the Americans could extradite Carvajal, the Dutch released him. Since Venezuela had named Carvajal a consul to Aruba – though the island had not formally received him – Carvajal claimed diplomatic immunity. Carvajal flew back to Venezuela on a private plane. The tail number of that aircraft, N9GY, matched one owned by a Delaware aviation firm owned by the Rincóns.

Carvajal’s brush with the U.S. government may have spooked Rincón. Or perhaps he merely sought a break from the flat Texas landscape. But in any case, Rincón’s business rivals told a Venezuelan journalist that Rincón moved to Spain weeks after Carvajal’s close call.

About a year later, in August 2015, Rincón purchased a $3.1 million mansion in the same Woodlands neighborhood as his first one. Listed as owners on that property are Rincón’s wife, Maria; a younger son, Roberto; and his daughter-in-law, Lucia.

According to a Venezuelan news report, Rincón returned to Houston that November. Maybe he thought he was safe in the United States – after all, more than a year had passed since the Carvajal incident.

But that same month, Rincón’s PDVSA associates pleaded guilty under seal in federal court to corruption charges. And the FBI had been interviewing his associates since at least 2012. On December 10, 2015, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Texas secured indictments against Rincón and Shiera. Their days as free men were numbered.

In the Houston suburb of Atascocita, 53-year-old Armand Castro worries about his aging parents. They live in Rincón’s hometown of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and, like Rincón, don’t leave their home. But their sentence is self-imposed and their prison is not a mansion.

Muggings have become so common that Hiran and Mira Castro fear even a midday walk to the neighborhood park. Maracaibo residents are so hungry and desperate they will mug a man for his shoes, let alone his wallet, Armand explains. So the retired Castros, who rely on a paltry government pension check whose arrival is as unpredictable as electricity in a city where surgeons operate under cell phone flashlights, pass the days in their single-family home. Mira, 86, tends her garden and feeds scraps to their five dogs. Hiran, 84, assures Armand he exercises, though his definition of a workout stretches credulity. He jogs from the backyard to the front, over and over again, the ten-foot concrete wall around the quarter-acre property a perimeter he will not breach.

The Castros barter with neighbors for staple goods, like flour and cooking oil. Hyperinflation has rendered the bolívar worthless (a 100-bolívar note equaled 15 U.S. cents in December). But Castro’s father holds onto the cash the family has at home, hoping it will regain value when the crisis passes. Armand urges his father to let go of this fantasy.

“I say it’s toilet paper, Papa. He’s just mad.”

The Castros rely on Armand and his two siblings, each of whom lives in Texas, to survive. Every few months, Armand packs several boxes of food and supplies that he ships through a courier in Katy. Medicine is especially important; his mother needs eyedrops Armand can buy only by traveling to Mexico or Central America, as he would need a prescription in the United States. His parents have no access to health care.

“You get sick in Venezuela, you might as well shoot yourself, because you cannot afford to go to a private clinic, or find medication,” Armand says.

Even knowing what shipments to send and when to send them is challenging. When the Castros speak by telephone, they know the government may be eavesdropping. Critics of the Maduro government have been intimidated, jailed or worse, so they must be careful. In their guarded conversations, nuance and subtlety are their cipher. When Hiran says their inventory is OK, Armand knows to start shopping. When he says they are “a little low,” Armand knows his parents may soon be starving.

The cooking oil in Venezuela is making people sick, so Armand must ship that. He also packs cornmeal, which jolts his memory to his arrival in the United States in 1979, when Armand could not find coarse flour anywhere to make arepas. Now he must confront the absurdity that Venezuela must import the main ingredient of a dish that is the staple of the country’s diet. Even items Americans pluck from gas-station checkouts have become Venezuelan luxuries. When Armand sent summer sausages, one of the few meats that do not require refrigeration, his father broke down in tears.

“Son, you know how much this is?” Hiran cried. “150,000 bolívars. This is like gold here.”

Armand loathes how his parents have been made to suffer. He has tried to persuade them to move to Texas, but they refuse. They want to live their final years in their homeland, a place Armand has not seen since before Chávez took power. If he does return, he suspects the government will conjure some excuse to extort him. He has made peace with the fact that he will miss his parents’ funerals.

An oil worker before Chávez stocked PDVSA’s leadership with sycophants, Armand says it is widely known in Venezuela that there is corruption in the country’s energy industry. He says the thousands of Venezuelans in Texas noticed when countrymen who had modest lifestyles back home began buying large houses in tony Houston neighborhoods.

“They come over here, and they’re going to live in a private subdivision with only 20 houses. And they all cost more than $2 million. That’s a red flag.” Armand says. “And then you see them driving those expensive cars. It’s like man, come on…They are traitors. They are thieves. People die because of them – because they want to have a rich lifestyle in the United States.”

He is pleased to see U.S. prosecutors finally going after the boligarchs. But he can’t help wondering: What took them so long?

Abraham Shiera’s Coral Gables mansion before he was charged in a federal sting.

Photo by Kristin Bjørnsen

Roberto Rincón was at his home in the Woodlands when federal agents arrested him December 16, 2015, the same day they collared Abraham Shiera in Miami. At the downtown Houston federal courthouse, a judge unsealed an 18-count indictment against the pair.

In addition to charges of conspiracy and money laundering, the government alleged Rincón and Shiera had violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a 1977 federal law that bars anyone connected to U.S. businesses from bribing foreign officials or governments.

Court papers give a glimpse of the scope of the pair’s fraud.

A detention order written by U.S. Magistrate Judge Nancy Johnson notes that in addition to his Woodlands mansions, Rincón has homes in Aruba and Spain. He also has 108 bank accounts, including $100 million in three Swiss accounts and “hundreds of millions of liquid assets elsewhere and available to fund a fugitive lifestyle.” Of the $1 billion scheme, prosecutors traced $750 million directly to Rincón.

In March 2016, Shiera pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA and one count of violating the FCPA. The government seized Shiera’s $900,000 yacht and $15 million in cash. He faces up to a decade in prison.

In June, Rincón took the same deal, but also copped to a fraud charge for filing false tax returns – the IRS was unwilling to ignore that he had the audacity to file $266,000 in income in 2011, when prosecutors estimate he earned $6.5 million. Rincón has forked over a Ferrari, a Lamborghini, and “a significant forfeiture of assets.” He faces up to 13 years behind bars.

To date, ten defendants have pleaded guilty in the Rincón/Shiera case. The eight known defendants are scheduled for sentencing on July 14, while the remaining two guilty pleas remain under seal.

Sources with knowledge of the case said the Justice Department is likely preparing more indictments. Prosecutors in the Southern District of Texas declined to comment on the investigation, but said in court papers as recently as February that the probe is ongoing.

Martin Rodil, a Venezuelan who lives in Washington, D.C., for years has played a vital role in providing the U.S. government with what it needed to begin prosecuting boligarchs: witnesses. He is a fixer, of sorts, who helps connect Venezuelans with viable information on corruption and drug trafficking with the appropriate American authorities. He has helped dozens of well-connected Venezuelans flee to the United States in exchange for testimony.

Rodil told the Houston Press Rincón is by far the most consequential arrest the Americans have made to date. Rincón was connected to the most senior officials in PDVSA, Rodil explains, including then-company president Rafael Ramírez.

“Everything he knows is gold for the prosecution,” Rodil says.

Otto Reich believes the U.S. government has barely scratched the surface of Venezuelan corruption here and has for years granted visas to boligarchs with few questions asked. The U.S. ambassador to Venezuela from 1986 to 1989 and an assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere Affairs under George W. Bush, Reich says corruption in Venezuela reaches far beyond PDVSA and is much larger in scope than the Maduro government admits or U.S. authorities have calculated.

“There have been people who have made money from the electric company, from the ports, importing food that doesn’t exist,” Reich says, ticking off a list that includes narcotics, political favoritism, bribery, and money laundering. “Literally billions and billions of dollars. And a very large part of those found their way to the United States.”

Reich was born into a Cuban family who fled to Miami after Fidel Castro – later an ally of Hugo Chávez – took power in 1959. He now runs a Washington, D.C. consulting firm that helps U.S. companies navigate Latin America.

American authorities have perhaps discovered 10 percent of the capital the boligarchs have smuggled into the United States, but Reich concedes this figure could be 1 percent or 20 percent. There is little way of knowing, since, Reich says, the boligarchs have become adept at hiding their money. For a hefty price, Reich says, they hire a “small army” of American bankers, lawyers, public relations firms, accountants, and investigators – in some cases agents retired from the federal agencies that conducted corruption probes.

The boligarchs want to be seen as legitimate, successful businessmen, and go to great lengths to create this facade. Reich said PR firms clean up their clients’ internet footprint, accountants advise on how to package assets to avoid U.S. government suspicion, and lawyers help the boligarchs distance themselves from illegal activity. Rincón at one point made a 22-year-old Montgomery County woman the head of one of his oil companies, without her knowledge, though PDVSA appears never to have caught on.

U.S. authorities do have one advantage in these investigations: Reich says many boligarchs, even as the Rincón/Shiera probe has landed 10 Venezuelans in jail, believe they will never be prosecuted.

“These guys are incredibly arrogant,” Reich explains. “And many of them are incredibly ignorant about our system, because they come from a system where there is no respect for the law. No respect whatsoever. There’s impunity.”

This may explain why Rincón returned to Texas in 2015, even though federal agents had been questioning his associates for years. And why boligarchs sometimes report incomes to the IRS that raise suspicions as to how they afford their mansions.

Reich expects to see additional corruption cases brought against Venezuelans living in the United States, but the boligarchs know just as well as he does that many will never face charges. Criminal cases take years to build and prosecutors are reluctant to try cases other than those that will bring surefire convictions, Reich says. A much more practical solution would be to deny visas to Venezuelans with dubious backgrounds and deport those who are suspected of bringing corruption to the United States.

Reich believes the Obama administration failed to properly vet boligarchs who settled in the United States between 2009 and 2016. The former diplomat says several federal agencies keep track of suspected criminals – including the state, treasury, and justice departments, but the government lacked the political will to weed out the visa applications from corrupt Venezuelans.

“I think we should be much more aggressive in denying visas once we know that people are unethical or corrupt,” Reich says. “And by aggressively, I don’t mean knocking down doors. We know who the corrupt people are. Revoke their visas. Don’t let them in.”

Every Venezuelan the Houston Press spoke with who was uninvolved in the Rincón/Shiera case said he or she supports such a visa crackdown.

Beyond the moral dilemma Americans face in watching Venezuela collapse, Reich believes the United States helps the Maduro government stay in power by providing a safe haven for boligarchs.

“Venezuelans are frustrated, but that frustration with what’s happening in their country is compounded by the fact that the people who enabled the Chávez/Maduro dictatorship to stay in power – you need money to stay in power – are in the United States,” Reich says. “Either living in the United States or working in the United States, or using our financial system. And enjoying the fruits of our freedom when they have extinguished that freedom in Venezuela.”

Patricia Andrade runs a nonprofit, Raices Venezolanas, that helps destitute Venezuelans who have just arrived in Miami.

Photo by Monica McGivern

Even the Venezuelans who have escaped the Chávez/Maduro government and built prosperous lives in the United States say they are burdened by the corruption that has ruined their country.

Arturo Betancourt was one of the PDVSA engineers purged by Chávez in 2002. Blackballed from the industry in which he was trained, Betancourt moved to Mexico, Chile, and Africa before settling in Katy in 2015. He now works for an American firm and lives in a middle-class home with his wife and youngest daughter.

Betancourt says he has steered clear of corruption schemes pitched by businessmen like Roberto Rincón – his father was a career oilman for a Chevron subsidiary in Venezuela who insisted on high ethical standards for his son. But colleagues and clients ask him about Venezuelan corruption in the oil industry.

“It’s a shame that you have to be stigmatized because these corrupt men are Venezuelans,” Betancourt says during an interview at his home. “It’s embarrassing because we know nothing about that issue. It’s remarkable what burden these guys have put on all Venezuelan people working in engineering and construction and oil and gas projects.”

Cinco Ranch and surrounding neighborhoods have become home to so many Venezuelans – more than 5,000 – that area of Katy has earned the nickname Katyzuela. Many work in the energy industry. Most have nothing to do with the corruption that has ruined their homeland. Except for the boligarchs: Four of the men in the Rincón case live within two miles of Betancourt.

To the east sits the 6,000-square-foot home of Charles Beech. In January he pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA, and court records do not indicate he has forfeited any assets to the government yet. But business must have been brisk enough for Beech to upgrade his family from a $309,000 home to their current $1.2 million home in 2013 – two years after court papers say he began scamming PDVSA.

“It’s not that you’re Republican and I am Democratic. It’s worse than that, because they are evil.”

To the west, Moises Millan owns a $385,000 house. Millan was valuable to Rincón because of his vast contacts within PDVSA, an associate of Rincón’s said. He pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to violate the FCPA and forfeited $534,000 to the government.

To the north, Alfonso Gravina owns a $920,000 home. Gravina, another PDVSA official who accepted bribes, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to commit money laundering and another for filing a false tax return. He coughed up $590,000 to Uncle Sam.

Just east of Gravina’s digs, José Ramos has a $375,000 house. Ramos was also a PDVSA contractor who accepted bribes from three businessmen whom court papers do not identify – including one, for $394,000, for the purchase of real estate in southern Texas. He pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering. From Ramos, the government seized $10.3 million, as well as three apartments and a home in Doral, Florida.

A fifth defendant in the case, Christian Maldonado, lists an address in the neighborhood on an apprentice electrician’s license. He pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiracy to commit money laundering and forfeited $165,000.

Betancourt says he does not know any of these men. Though he doesn’t need to meet them to form an opinion: They should be in jail, he says, and the government should take every dime they stole and return it to the people of Venezuela. The boligarchs owe that to people like Betancourt’s mother and sister, who live in Caracas, Venezuela’s capital and the city with the world’s highest murder rate in 2016.

The Venezuelan community in Katy is welcoming, Betancourt says, and he often attends parties with his wife. The topic of the current crisis always comes up, and Venezuelans are quick to express their frustration with Maduro. Most Venezuelans in Katy are appalled at the ruling government, including Betancourt. But he says there are a few Chavistas (supporters of Chávez/Maduro).

Betancourt refuses to associate with Chavistas, let alone invite them to his home. The gulf between Chavistas and opponents of the government cannot be explained away as differences in political opinions, he stresses. There is no neat analogy to American politics.

“It’s not that you’re Republican and I am Democratic,” he explains. “It’s worse than that, because they are evil. It’s like after the Second World War, you find a Nazi officer that you know did very bad things. And you find someone that is trying to defend that position.”

In Betancourt’s mind, there is little difference between the Chavistas who participate in corruption schemes and those who simply support Maduro amid Venezuela’s descent into chaos. A Venezuelan would not support the government, he reasons, unless he or she was benefiting in some way.

Avoiding boligarchs in South Florida, home to more than 50,000 Venezuelan immigrants, is more difficult. Patricia Andrade runs a nonprofit, Raices Venezolanas, that helps destitute Venezuelans who have just arrived get on their feet. She also tries to keep track of boligarchs who settle quietly in Miami.

Juan Hernandez, a former employee of Shiera and the eighth known defendant in the case, owns a $627,000 home in a gated neighborhood in Weston, a city home to more than 6,000 Venezuelan immigrants. He pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiring to violate the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Andrade researches the owners of Venezuelan restaurants and shops. If they are Chavistas, she boycotts their businesses and encourages others in the vocal anti-Maduro community in South Florida to do the same. Because of her advocacy, boligarchs sometimes recognize her and try to intimidate her – she recalled an incident in which men she suspected of being Chavistas photographed her as she ate in a restaurant.

Yet she persists, and has found success. She says she discovered a former mayor of Barquisimeto living in a $500,000 home. She has submitted a list of 300 suspected boligarchs to the State Department. She wrote a letter to President Barack Obama asking how corrupt Venezuelans could secure visas so easily while applications from poor Venezuelans languished in processing.

“They come to the U.S. and live like a king. They live like millionaires. But it’s not under investigation,” she says, exasperated. “I feel like I’m living in Venezuela.”

If Roberto Rincón is given the maximum sentence of 13 years when he appears before a judge in July, he will get out of prison when he is 70 years old. Shiera, on the hook for at most ten years, would be a free man by age 64. U.S. authorities are unlikely to recover all the money the pair swindled out of PDVSA, so the boligarchs will be free to live out their lives, outside the United States.

Two futures lie before Valentina; one if she leaves Venezuela, and the other if she remains.

There is no guarantee she will immigrate to the United States. Her father, JJ, arrived in Houston on a student visa and since he graduated from college in 2016 has had a temporary work permit. He must secure a green card to be able to bring his daughter here. Another option would be for JJ to persuade his relatives in Texas, who are permanent residents, to formally adopt Valentina. Her chance at a normal childhood, and perhaps even her survival, depend on it.

Valentina’s mother, Esmeralda, who also spoke to the Houston Press by telephone from Venezuela, says sending her only daughter away will be painful. But she believes a new life in America will open doors for Valentina that she fears will be forever closed in Venezuela.

“Even if Valentina stays here and gets a degree, she’s going to be unemployed or have minimum-wage work,” she explains. “She’s not going to achieve many things or have a good quality of life.”

Valentina wants to be a teacher or a chef when she grows up. She wishes she could help the garbage pickers she sees. If she had the means, she would feed them, clothe them, clean them up.

The tragedy of Venezuela is it has too few Valentina Villafanes and too many Roberto Rincóns. As long as that remains the case, Armand Castro believes, Venezuela is condemned to continue on its path toward a failed state. Venezuela’s economy contracted by nearly a fifth last year, and forecasts for 2017 are grim.

Arturo Betancourt, the former PDVSA engineer, estimates his country will need two decades to recover from the wounds inflicted by the boligarchs over the previous two. During the course of an hourlong conversation at his kitchen counter, he recounts how his country has been looted and betrayed, his friends and relatives subjected to senseless suffering. He returns, perhaps unintentionally, to a simple phrase, two words that explain the ever-present thought lodged in his mind the past 18 years.

“This madness.”