Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

Audio By Carbonatix

In late 1982, Phil Sandlin was doing paperwork when a young, clean-cut Vietnam War veteran who worked as a parking valet in South Beach walked into the Associated Press office with some negatives. He said he’d snuck onto a film set on Ocean Drive and snapped a few shots of Al Pacino at work.

As he flipped through images of Pacino stalking in front of art deco hotels, Sandlin quickly realized he had something special. One shot particularly grabbed him: Pacino angrily firing a pistol at a grimacing actor, whose head exploded into a fake bloody mess.

“The photos were outstanding,” Sandlin recalls of Bill Cooke’s Scarface shots. “I still don’t know how he got on set, but he had the gift of gab, so he probably just BS’ed his way right in there.”

Those candid Tony Montana shots, which the AP bought just as Miami’s Cuban-American leaders angrily slammed the film’s portrayal of the exilio community, ran in hundreds of papers across the nation. The images marked the beginning of Cooke’s decades-long collaboration with photo editor Sandlin. The Cuban-gangster flick would be one of scores of iconic Miami moments the self-taught photographer, who died this past May, captured firsthand.

He was a gravelly voiced, fearless curmudgeon who gravitated toward hard-nosed beat reporters.

When hundreds of thousands of Cubans poured into Miami during the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, Cooke documented the chaos. When University of Miami quarterback Vinny Testaverde and his team roared to antihero football fame, Cooke followed them at the airport. When Donna Rice imploded Gary Hart’s presidential ambitions on the boat Monkey Business, Cooke was ready with racy photos of the model.

“He’s the Forrest Gump of Miami history,” documentary filmmaker Billy Corben says. “He was everywhere shit was going down.”

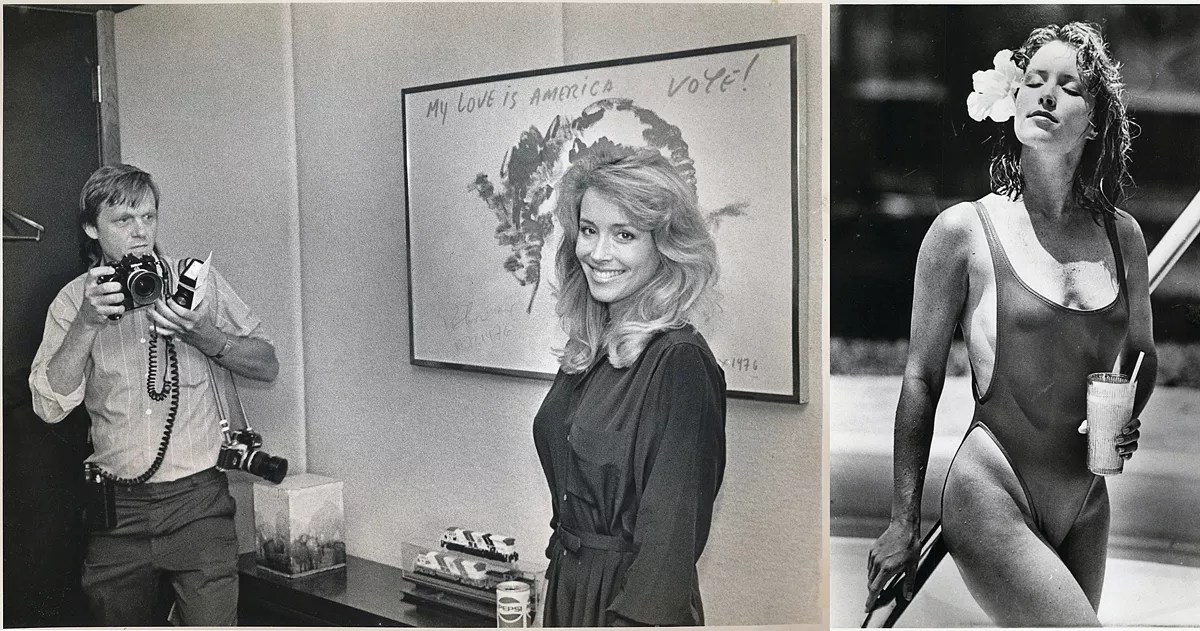

Bill Cooke photographs Gary Hart’s mistress Donna Rice. She poses for Cooke in 1984. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photos via the Bill Cooke archives

Unlike Gump, Cooke was snapping away the whole time – and quietly assembling a formidable archive of all that Magic City history. After Cooke’s death, Corben and fellow filmmaker David Cypkin discovered more than 60,000 photos stashed in the photog’s small room at a bayfront retirement home. The two have spent the past six months sorting and scanning the massive archive, which will be donated to HistoryMiami – and they have been constantly surprised by what they have found.

“We had no idea the extent of his collection,” says Corben, who’d been friends with Cooke for years by the time he died. “We knew about his career, obviously, but whenever we’d hit him up for old pictures for any film projects, he’d claim to not have saved that much.”

Even in Miami’s tropical Casablanca of lost souls and eccentric wanderers, Cooke was a unique character. Born in Atlantic City, he was raised in Miami by a man he told friends was an abusive, alcoholic father. Cooke was drafted into the Army in the late ’60s and took a camera along when he was sent to Vietnam. His love affair with film began in the bullet-scarred rice paddies, where Cooke photographed daily scenes of young soldiers goofing in tents and posing stonefaced on tanks.

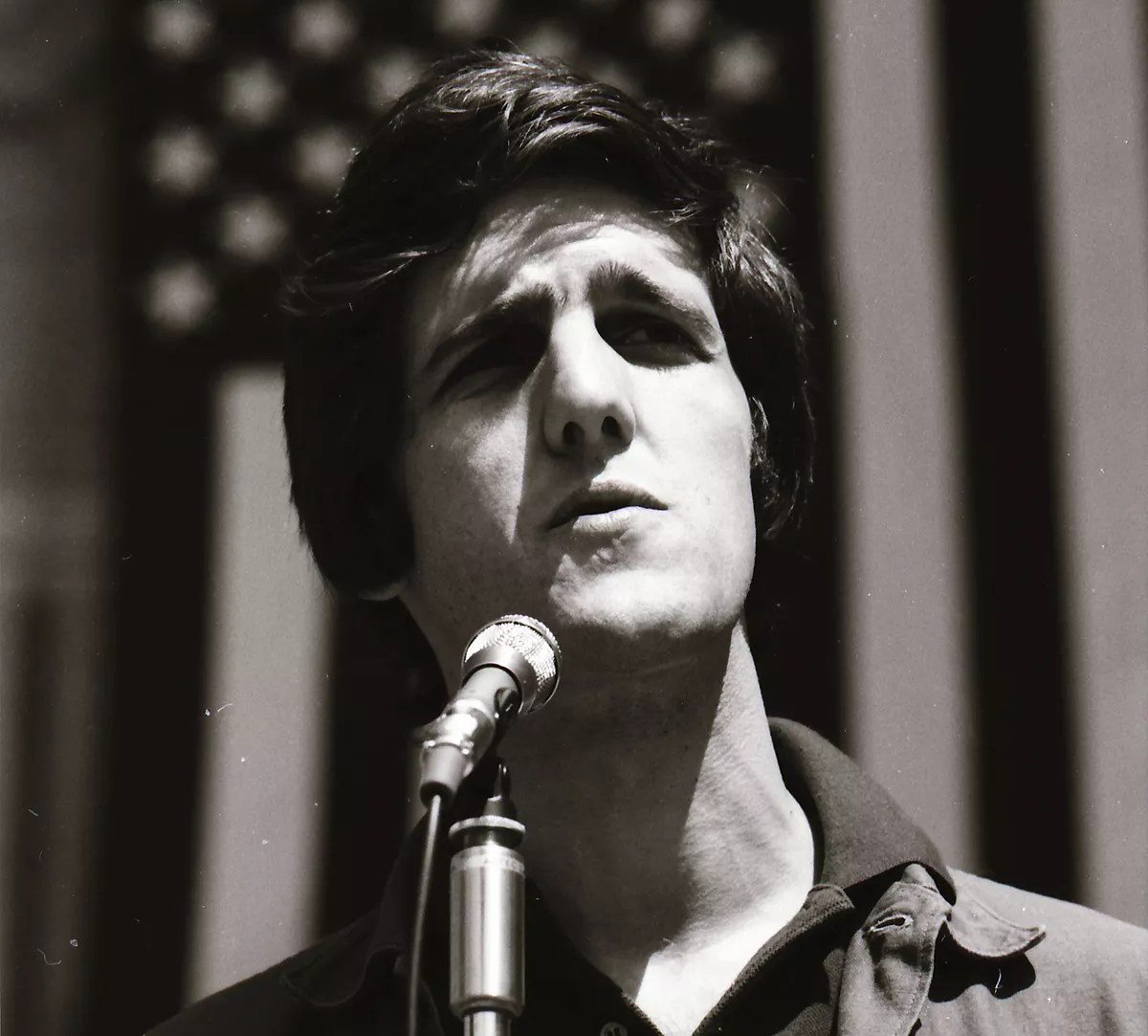

John Kerry speaks at a protest in 1971. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

By 1971, he had returned to the States and lugged his Nikon to Washington, D.C., where he documented the massive antiwar protests that erupted around future senator and secretary of state John Kerry’s stirring testimony to Congress demanding an end to the war. When Cooke made his way back to South Florida, he got by on odd jobs at South Beach hotels while shooting scenes of daily life as the neighborhood shifted from a seedy retirement community to a drug-addled wasteland.

His Scarface pics were the beginning of a long working relationship with Sandlin, a honey-voiced Southerner who mentored scores of young photographers around South Florida in his decades at the AP. Sandlin saw a unique talent and personality in the Vietnam vet.

“He had a very good eye, but Bill was quite a newsman too, photography aside,” Sandlin says. “Bill would always call me up and give me tips: ‘Did you know the mayor will get served with papers today?’ And I’d always say, ‘Where on Earth did you get all this information?'”

The answer was simple: He was an irrepressible talker, a gravelly voiced, fearless curmudgeon who gravitated toward hard-nosed beat reporters. He befriended legendary Miami News journalist Milt Sosin and Miami Herald crime master Edna Buchanan to learn their tricks. He’d sidle up to police spokespeople and mayors’ aides and lived for news tips.

Sandlin and Cooke grew close as the editor fed the freelancer a steady diet of breaking-news and sports gigs. Once, they lost track of time while editing photos after a Dolphins game and walked to the exit, only to discover they’d been locked inside the stadium.

“Bill was really pissed that day, just letting it fly at the security guards,” Sandlin remembers. “He finally found a way to climb over a fence so we could escape.”

He always followed his gut — no matter the collateral damage.

In 1989, the biggest story in Miami was Manuel Noriega’s arrest on federal drug-trafficking charges. He was flown in shackles to Miami’s downtown courthouse, where a mass of reporters and photographers jockeyed for the chance to get the first mug shots of the Panamanian strongman. Cooke had an idea to beat the competition.

“One of my other freelancers had a brand-new Lincoln, and Bill said, ‘They’ll let you drive that thing right under the courthouse,'” Sandlin says. “Sure enough, this photographer drove this shiny Lincoln into the courthouse and got him the picture while everyone else was parked out front.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger smokes a stogie on the set of True Lies. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

Four years later, Cooke’s ingenuity led him to his most famous – and lucrative – photos. As he later recounted on his blog Random Pixels, Cooke began a day in a gaggle of other photographers staking out Jose Canseco’s house after the roided-up slugger had been arrested for ramming his Porsche into his wife’s BMW. Bored, Cooke flipped through a tabloid and read that Madonna was in town to take photos for her new book, Sex.

On a whim, he tried to find her shoot in Miami Beach, but after coming up empty, he headed to Key Biscayne to unwind for the day. On his way, he passed Vizcaya and noticed a sign directing “crew” down a back alley. Cooke quickly turned down the passageway, parked his car, and – through some bushes – spotted a topless Madonna on set. He snapped a few dozen photos through a 300mm lens – sure the whole time “they [were] going to hear me and come outside the gates and beat the crap out of me,” he later wrote. He escaped and rushed to develop the salacious pics, which his agency whisked onto a Concorde flight to Europe, where British tabloids bid wildly on them.

“One writer says that I made a million dollars from the pictures,” Cooke later wrote on his blog. “Not even close. But I did very well.”

Cooke could be difficult, especially if he sensed any ego or pretentiousness. Over the years, he’d abruptly cut off friendships over perceived slights, only to quickly restart them with a phone call and no mention of the previous offense. And he always followed his gut – no matter the collateral damage.

Mourners visit the Versace memorial. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

“When Versace was shot, I wanted Bill to go down to the morgue if just in case they were going to bring the body out. I’m watching the TV coverage, and all of a sudden I see Bill on Miami Beach!” Sandlin says. “I said, ‘What the hell are you doing over there?’ He just decided he might get a better story there than at the morgue.”

Cooke was most active covering Miami through the ’80s and ’90s – arguably the news peak of the Magic City, from the cocaine cowboys drug wars to the celebrity invasion of a revitalized South Beach.

“Considering it was such a volatile period in Miami’s history, this was a news town in those days,” says Al Diaz, a longtime Herald photographer and friend of Cooke’s. “Every day something was going on, and Bill was there to shoot a lot of it.”

After Hurricane Andrew leveled South Dade in 1992, Cooke captured hundreds of scenes of devastation and emotional rescue work. When 2 Live Crew’s Luther Campbell won his decisive First Amendment judgment in 1994, Cooke captured the rapper’s joyous fist-pump with attorney Bruce Rogow. As hundreds of journalists camped out in Little Havana in 2000 to document the legal tug-of-war over Elián González, Cooke photographed the media madness. He wasn’t above playing paparazzo, either, and over the years snagged unscripted Miami pics of everyone from Arnold Schwarzenegger to Andy Garcia to Gloria Estefan.

Firefighters extinguish a warehouse blaze. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

But he never stopped shooting ordinary life. Among his most affecting photos are of firefighters battling a raging warehouse blaze, and an undated black-and-white shot in downtown Miami of a dirt-streaked homeless man sprawled across a bench as two attorneys in tailored suits stroll past, oblivious.

By the mid-2000s, Cooke’s professional photojournalism slowed as personal battles with alcohol and pulmonary disease arose. He occasionally freelanced for New Times, though his unpretentiousness sometimes came across as sloppiness. One day, editor Chuck Strouse got a call: “Why are you sending a homeless guy to take pictures at my restaurant?” Strouse phoned Cooke, and they shared a hearty laugh.

As his photography gigs dried up, Cooke reinvented himself as a feisty, often-hilarious blogger. On Random Pixels, he broke news about Miami Beach politics and internal scandals at the Herald, which he regularly attacked with a poison pen. He picked targets such as Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine – whom he nicknamed “Mayor Dickhead” and Photoshopped a NSFW image to match – and found sources to leak embarrassing stories that daily journalists had to follow.

Elián González smiles for reporters. See more photos from Bill Cooke’s archives.

Photo via the Bill Cooke archives

Cooke developed a habit of relentlessly calling every reporter in his Rolodex until they picked up to hear his latest grimy-voiced tip. Friends like Corben, Cypkin, and Diaz would deliver meals and cough drops to his North Miami apartment and later the retirement home in Edgewater.

In May, Cooke died of pulmonary fibrosis at the age of 70, surrounded by his photos. They were everywhere: stuffed into desk drawers, crammed into plastic bins, printed out in albums, and burned onto CDs.

When Corben and Cypkin walked into his room about a week after his death, they were stunned by the number of prints in the small space. Then they opened his closet.

“That’s when we finally realized just how many he’d kept,” Cypkin says. “That closet was pure storage, just bins and bins full of negatives.”

With the permission of Cooke’s sister, Linda Yero, the pair arranged to donate the photos to HistoryMiami, which maintains an archive of 1.5 million photographic prints and negatives dating to 1883. Cooke’s photos will join another recent donation, from longtime Herald photographer Tim Chapman – but not until Cypkin and Corben finish scanning all the pictures.

To date, Cypkin estimates he’s scanned about 20,000 photos. He guesses another 10,000 are probably worth including in the donation.

“We’re only now realizing how extraordinary the collection really is,” Corben says.