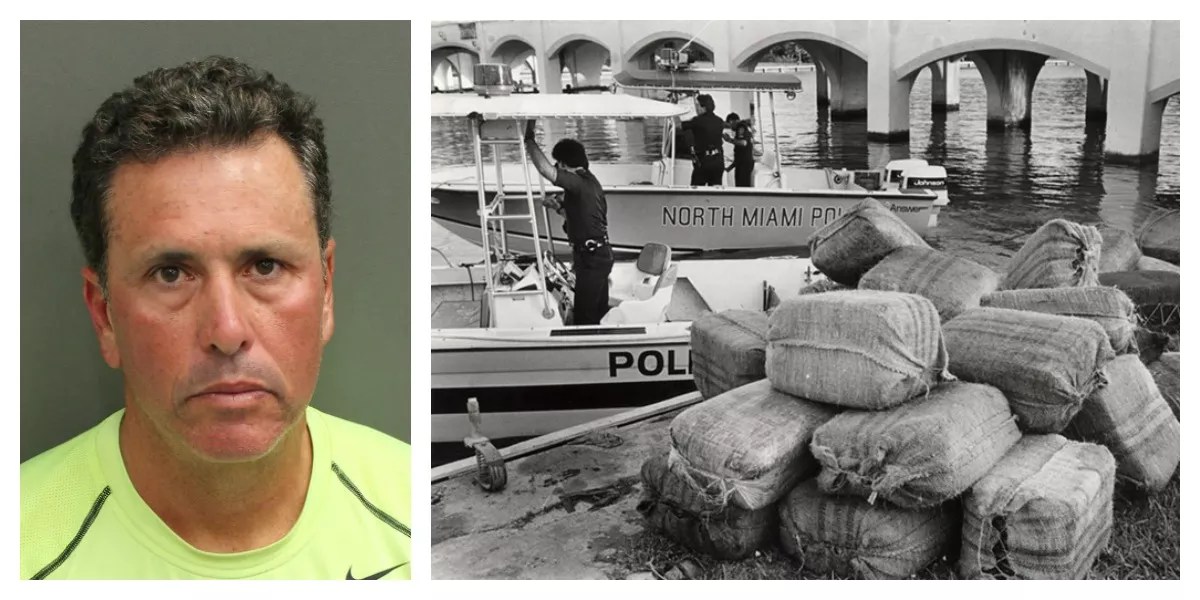

Orange County Jail/HistoryMiami

Audio By Carbonatix

Willy Falcon and Sal Magluta ran the largest smuggling ring of the Miami’s cocaine-fueled heyday. The two high-school friends built a $2 billion trafficking empire, which snaked through multiple banks, states, properties, and even one speedboat-racing league. Though “Willy and Sal,” as they were known, were eventually caught and convicted after nearly a decade of court proceedings in the 1990s, Willy’s brother, Gustavo “

Many believed Gustavo Falcon had either fled the country or died. But all this time, Falcon was living a few hundred miles from Miami, in Kissimmee. This past Wednesday, U.S. Marshals nabbed Falcon after he spent more than a quarter-century in hiding. He’d just returned from a bike ride.

Willy and Sal’s story is film-worthy – and Cocaine Cowboys director Billy Corben is working on turning their tale into the next installment of his infamous, drug-fueled docuseries. But long before Corben began working on his film, then-New Times staff writer (and now CBS 4 reporter) Jim DeFede wrote a book’s worth of copy about Willy and Sal’s sordid, surreal, and near-impossible true story. Here are those stories:

It was a day for redemption, a chance to win back a little respect after years of embarrassment. Everyone wanted to be in on the arrest of Willy and Sal, to be able to say they’d been there when the legend died. So on a rainy afternoon last October, as darkness fell over Sal Magluta’s palatial La Gorce Island home in Miami Beach, dozens of federal, state, and local agents stood by as a specially trained, 25-man assault team from the U.S. Marshals Service stormed the house and captured the elusive Magluta. Five hours later, with the rain still pouring down, the same team of agents raided the Fort Lauderdale mansion of Willy Falcon.

Inside the houses, they found nearly one million dollars in cash and jewelry, a small amount of cocaine, and a kilo of gold. Chump change. Because in the age of the cocaine cowboy, Falcon and Magluta weren’t just hired hands. They owned the ranch. From 1978 right up until the day the two were finally arrested, federal prosecutors say the Miami Senior High School dropouts acquired more than $2.1 billion in cash and assets by smuggling at least 75 tons of cocaine into the United States.

In their heyday, according to prosecutors, Augusto Falcon and Salvador Magluta controlled the largest cocaine smuggling organization on the East Coast and one of the top five in the world, a massive assemblage of planes and boats that funneled coke from the Colombian cartels in Medellin and Cali to the streets of Miami, New York, Washington, D.C., Charleston, South Carolina, and dozens of other cities across the United States.

The Further Adventures of Willy and Sal (1993)

As the garage door swung open, Gonzalez floored the accelerator. Sure enough, police and federal agents were lying in wait. But Gonzalez’s sudden departure caught them off guard. They quickly rushed to block all exits from the hotel. As Gonzalez raced wildly around the parking lot trying to escape, agents unleashed a wave of gunfire. The Blazer crashed through a chainlink gate, but the street ahead was barricaded. Back into the parking lot he charged, this time lying on the floor and steering blindly with his left hand so as to avoid the barrage of bullets coming from every direction. Gonzalez then rammed a pair of police cars by one of the exits and knocked them aside. Out of control and dragging a large chunk of chainlink fence, he smashed into a parked car before stranding himself on an oleander bush half a block from the hotel.

More than 130 bullets were fired in the melee, all by police and federal agents. The chassis of the Blazer was riddled with holes, all four tires were blown out, every window shattered. Even Gonzalez’s prized rear spotlight took a hit. When officers came running, Gonzalez’s female friend stepped from the car with a only few minor scratches caused by flying glass. Gonzalez himself ended up with just a couple of superficial gunshot wounds – to his left arm and shoulder. Ever defiant, he boasted that he would have gotten away had his vehicle’s drive shaft not broken.

The Trial of Willy and Sal (1995)

If America learned anything from the O.J. Simpson trial, it was the value of the courtroom as theater. But not every blockbuster can emanate from Hollywood, and most will never be televised. And so it is hardly surprising that the last great drug trial of the cocaine-cowboy Eighties is taking place without much notice – from the people at the Nielsen ratings service or anyone else. The drama on the tenth floor of the federal courthouse in downtown Miami began unfolding six weeks ago, with Assistant U.S Attorney Christopher Clark introducing to the jury of six men and six women the two expensively dressed men sitting across the room amid their not-quite-as-well-attired phalanx of attorneys.

Clark described the defendants as a pair of high school dropouts who had attained prodigious wealth through a perverse version of the American success story. These two men, he told the jury, embodied the very history of the cocaine explosion, not just in South Florida but across the nation: an influx of white powder that stoked the local economy and altered the political landscape.

“May I present to you,” Clark said in his opening statement, “the case of the United States of America versus Augusto Guillermo Falcon and Salvador Magluta. Willy and Sal. Los Muchachos. The Boys.”

In Pursuit of Willy and Sal (1999)

Embarrassed after suffering the biggest loss of a narcotics case in U.S. history, federal prosecutors in Miami are preparing a major new indictment against legendary drug kingpins Willy Falcon and Sal Magluta. Since their failure three years ago in the original Falcon and Magluta trial, in which the pair was accused of smuggling into the United States 75 tons of cocaine worth $2.1 billion, prosecutors have managed to keep them in jail on a variety of relatively minor charges. The effectiveness of that tactic, however, is nearing an end, and federal prosecutors must either come up with a new, substantive indictment this year or risk having one of them slip from their grasp.

In Pursuit of Willy and Sal, Part Two (1999)

On the morning of January 6, on the ninth floor of the James Lawrence King Federal Courthouse, the man for whom the building was named, Senior U.S. District Court Judge James Lawrence King, presided over what will long be remembered as one of the more bizarre moments in South Florida’s legal history. The occasion was the criminal trial of Miguel Moya, the erstwhile foreman of a jury that three years earlier had acquitted a pair of infamous cocaine smugglers, and who now stood accused of taking a bribe in that case. Joining Moya in the dock were his parents, Jose and Rafaela, charged with helping their son launder the alleged payoff.

Their defense would be as novel as any seen in a federal courtroom in the Southern District of Florida, a uniquely Miami-style strategy that poked a hole in a case many prosecutors thought was puncture-proof. But that would come later in the day.

At 10:00 a.m. Judge King summoned the jury and instructed prosecutors to proceed with their opening statement. “In October of 1995 there commenced a trial in the United States District Court here in the Southern District of Florida,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Edward Nucci began. “It was a trial of the United States versus Augusto Guillermo Falcon, Willy, and Salvador ‘Sal’ Magluta. It commenced before the Honorable Federico Moreno in this very courthouse. Those defendants, Falcon and Magluta, were charged with running a continuing criminal enterprise in the narcotics business. The allegations were that they ran this enterprise from 1978 all the way through 1991. That they were drug kingpins, in other words. The allegations were that they made in excess of two billion dollars running that drug enterprise.

“And in that trial a jury was impaneled, much like you today. They were sworn to try the case well and fairly, as you have been. But the government will prove to you … that there was a traitor to the due administration of justice on the jury in the Falcon and Magluta case.

“There was someone who was bought and paid for by the Falcon and Magluta organization who was not going to try that case fairly and impartially, who had received money in exchange for sitting as a juror. And the government will prove that that individual is the defendant, Miguel Moya.”