Photo illustration by Michael Campina

Audio By Carbonatix

The black people in the building knew it first.

Devon Ross, a maintenance worker at the Mirador 1000 condominium in South Beach, felt it when the new condo board members brushed past him in the hallway as if he were invisible.

Valerie Crawford, a longtime resident, sensed it when she heard about plans to get rid of the “riffraff.”

Amani Ayers, a longtime resident who worked at the front desk, recognized it when “law and order” became a topic of discussion at association meetings.

But for Alan Shugarman, a white resident who had served on the three-person condo board for more than a decade, it took a lot longer to see the racism at play in the 16-story luxury high-rise on Biscayne Bay.

“There were all these things that didn’t make sense individually,” he says. “As the pieces all came together, I realized what was happening.”

“It was quite disheartening for me as a person of color… Here I was thinking things had gotten better.”

At least nine former and current residents and employees have now come forward with accusations of racial discrimination inside the Mirador 1000, an upscale condo building with its own hair salon and convenience mart where two-bedroom units are listed for up to $800,000. The majority of the allegations are against the two women who joined Shugarman on the board in 2016: Arianna Aguero and Silvia Merino. According to one employee, Merino used the N-word to disparage two black women who worked at the front desk, while Aguero reportedly remarked to a property consultant: “The staff is too dark. I want to make some changes.” In the end, at least seven black employees say they were fired, forced out, or quit due to harassment.

“I knew – we all knew, all the black people that worked at the Mirador – they all felt it was just overt racism,” says Ayers, who was let go shortly after the new board was installed.

George L. Fernandez, an attorney representing Aguero and Merino, says the two women “categorically deny” those claims of racial discrimination. “Simply put, these outrageous allegations are untrue,” Fernandez wrote in an email to New Times.

Yet the claims of what happened at the Mirador – as described in interviews with six employees and three residents, as well as written statements and depositions from three others – suggest how small condo boards can effectively redline a place like Miami Beach, where black residents make up only 4 percent of the population. Despite Obama-era Housing and Urban Development (HUD) rules meant to protect residents from hostile-environment harassment, proving racial discrimination in housing still remains difficult.

“Unless it’s

To black residents and employees at the condo, the story is also a testament to what Ayers calls “the Trump factor” and how the president’s racist rhetoric has lowered the bar for how people treat one another in their workplaces and communities.

“He empowered a lot of people to say the things they’ve always thought,” she says.

Crawford, one of the building’s few black condo owners, says the discrimination became so overwhelming she made the tough decision to move out of South Beach last summer. For more than 30 years, she loved her bayfront view and walkable neighborhood. But, she says, “spiritually, it was darkness.”

“Too many people are sitting on the sidelines letting people be oppressed as long as it doesn’t happen to them,” Crawford says. “It was quite disheartening for me as a person of color and a person on the Beach. Here I was, thinking that things had gotten better.”

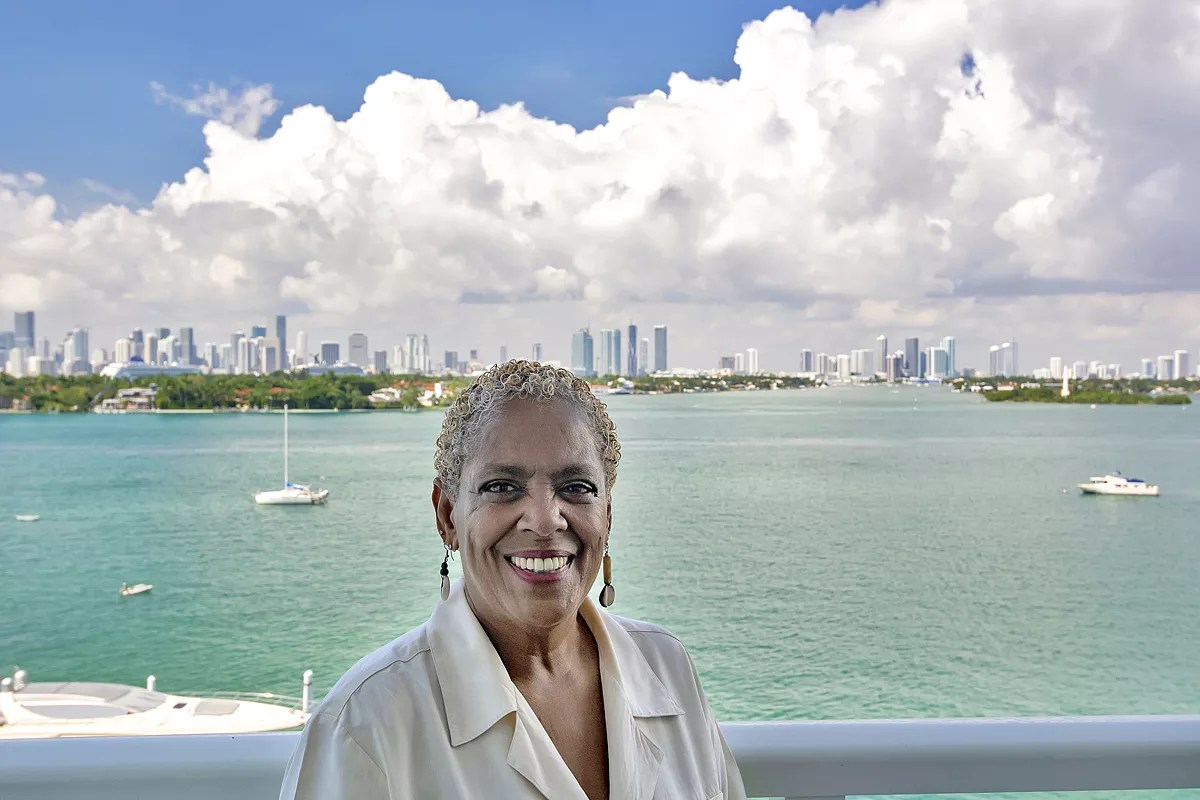

Amani Ayers lived in the Mirador 1000 for nearly three decades and worked at the front desk until she was fired in 2016.

Courtesy of Amani Ayers

Originally from Baltimore, Amani Ayers ditched her job in sales and moved to Miami Beach in 1983, shortly after turning 30. Long before raw food and juice bars were trendy, she opened Our Place Natural Foods Eatery, a health-conscious restaurant that served veggie burgers, wheatgrass juice, and homemade hummus to a hungry lunch crowd on Washington Avenue. Ayers, a gregarious people person who had been a vegetarian since the age of 18, was keen to prove that vegan food could taste great and turn a profit. Her bet paid off: In less than a year, Our Place had garnered a steady crowd of regulars and eventually grew into one of South Beach’s premier folk music venues.

The quirky restaurant was well established by the time Valerie Crawford arrived in Miami Beach in 1989. Sick of the cold winters in Philadelphia, a 27-year-old Crawford had left her job in the insurance industry and moved to Florida to become a personal trainer. A vegetarian since the age of 13, she soon discovered Our Place and struck up a friendship with Ayers.

The two women learned they had much in common. Both had graduated from predominantly white schools – Ayers from Colgate University and Crawford from the University of Pennsylvania – and were used to inhabiting white spaces. Crawford, a high-school track star, had studied political science and sociology, while Ayers majored in anthropology and sociology.

Not long after meeting, they decided to become roommates and began searching for the perfect two-bedroom. When they found a waterfront apartment at the Mirador, it just felt right. One glance out the window at the Miami skyline, and they were instantly sold.

“It could make a bad day good, walking in and seeing that view,” Crawford says.

“Living in the Mirador was not an issue until it became one in 2016.”

At the time, Crawford and Ayers were among only a handful of black renters in the building, which has more than 400 units. On more than one occasion, older white tenants confused them for hired help, asking, “Whose girl are you?” when one of them would step into the elevator.

“I just thought, This is the Jim Crow South,” Ayers says. “It just is what it is.”

Crawford sometimes joked she was “Helen’s girl,” a reference to her mother. She also brushed it off as a generational difference.

“I took that as women of a certain age in a certain era,” she says. “It was offensive, but it wasn’t in the sense that it was derogatory. Plus, it was older women, and I was raised to be respectful.”

Coming from up North, Crawford says she was unfamiliar with Miami Beach’s long history of racial tensions. She didn’t understand the context when people asked her why she would choose to live on the Beach of all places in Miami.

“I had no sense of the prejudice issues of Miami Beach and why black people didn’t go to Miami Beach,” she says. “That wasn’t my consciousness nor my history. I didn’t learn that until later.”

From almost the very beginning of its existence, though, Miami Beach was a place where black people were treated as second-class citizens. Before the barrier island was fully developed, black Miamians rode a boat to what was then called Ocean Beach and enjoyed it alongside whites. But as the city of Miami Beach was incorporated in 1915 and grew into a ritzy resort town, black residents and visitors were shut out to accommodate the white upper class.

One such group was a small community of black laborers and their families who settled near 41st Street and Pine Tree Drive in the early 1920s. After the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, their homes were torn down in the name of development, and the community was forced to disperse. They weren’t allowed back: The new deeds on the land prohibited black people from living in the neighborhood except in servants’ quarters.

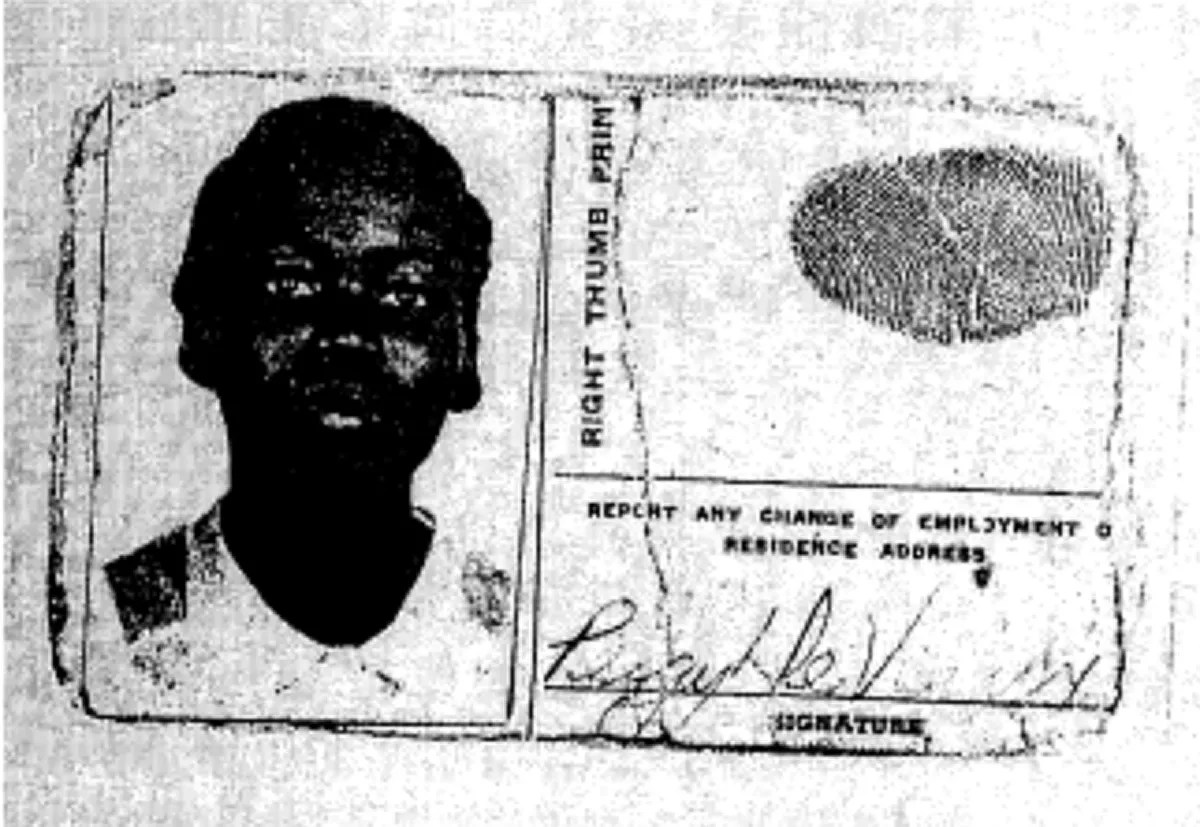

The most explosive change to race relations, however, came when the city passed Ordinance 457 in 1936. The law required all service industry and domestic workers in Miami Beach to register with the police department and carry an ID card at all times. Although the law did not specifically target black workers, it was selectively enforced against African-Americans. The ordinance effectively barred black people from staying on the Beach overnight – even well-known entertainers who came down to perform in nightclubs in hotels, including Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong.

Black people were also banned from using the beach until

By the time Ayers and Crawford moved into the Mirador in the late ’80s, however, they noticed few vestiges of Miami Beach’s racist history, other than the occasional offensive comment in the elevator. When the building converted into a condominium in 2005, they were among the first owners, buying a unit to share. For almost 30 years, the two women lived in peace with their neighbors at their condo on the bay.

“Living in the Mirador was not an issue until it became one in 2016,” Ayers says.

Beginning in 1936, black workers in Miami Beach had to carry an ID card at all times.

Courtesy of Ariel Sheen

As Donald Trump began his presidential campaign in August 2015 with a speech calling Mexicans “rapists” and criminals, the condo association at the Mirador 1000 was gearing up for its own election. In January 2016, residents in the 463-unit building reelected Alan Shugarman as vice president and installed Arianna Aguero and Silvia Merino to serve for the first time as president and secretary-treasurer.

Aguero and Merino did not respond to calls and letters from New Times, and their attorney did not make them available for interviews. But according to her social media profiles, Aguero, who is 52, grew up in Tampa and attended an all-girls Catholic prep school before heading to the University of Florida, where she joined the Delta Delta Delta sorority and majored in business administration and marketing. Since 2012, she has worked in the marketing department of a Miami law firm. A 2017 South Florida Business Journal article says she was previously a classical pianist, makeup artist, and extreme skier. She bought her two-bedroom condo at the Mirador in February 2005 for $394,000, according to property records.

Merino, age 57, worked as a TV producer in Peru before coming to Miami, where she has worked as a programming executive in Spanish media since 1996, according to her LinkedIn profile. She shares her studio apartment, which she purchased in March 2005 for $265,000, with three Yorkshire terriers.

Before they ran for the board, Aguero and Merino weren’t particularly vocal at association meetings. According to Ayers, Merino rarely attended, while Aguero dropped in occasionally but seldom gave her opinion.

“I’m old enough and black enough to know ‘riffraff’ was a code word.”

Shortly after they were elected, however, the women called a meeting of the building’s employees. Ayers says the two new board members promised they would be loyal to the staff and said they wanted the team to feel like a family. But something Aguero said seemed to put everyone on edge.

“It was the fact that she made a point of saying she had worked for a lot of lawyers and [mentioning] her husband’s law firm and, between the two of them, they worked for the two largest law firms in the state of Florida,” Ayers says. “The whole atmosphere in the room – none of us felt like we trusted them.”

In February, the building’s longtime property manager, Sheebra Brown, a black woman, went on maternity leave, and Richard Parker, a white condo consultant, was hired in the interim. Ayers, who had worked as a building concierge on and off for ten years, says she was behind the front desk one day when Parker stopped by.

“What he said specifically to me was, ‘I’m going to clean up this mess around here.’ He was making a kind of joke,” she remembers. “He said something to the effect of, ‘I’m going to clean up the front desk, clean up the plantation look around here.'”

Ayers was so taken aback she didn’t know what to say.

“To tell you the truth, I was speechless, because I couldn’t believe what he was saying,” she says.

Parker tells New Times the conversation never happened and says he doesn’t remember anyone by Ayers’ name. “That’s insane,” he says. “The whole thing is ridiculous.”

But other employees say they too felt the atmosphere change. Devon Ross, a maintenance worker who had been at the building for about six years, says Aguero and Merino would ignore him when they passed him in the hallway even when he said hello.

“You didn’t feel wanted no more. You felt like you were being tolerated,” he says.

Dennis Daley, the former onsite security supervisor, says Aguero talked down to the workers in the building.

“When the board changed about two years ago, that’s when everything really went downhill,” says Daley, who is black. “I’m not going to put a label on it and say they discriminated against us… but I just thought that

Other employees felt differently. Manny P., the building’s Spanish-speaking chief engineer, says it was clear that racism was at play in the way Aguero and Merino interacted with black workers.

“Definitely, definitely,” he says. “They’re really racist people.” (Manny asked New Times not to use his last name because he fears future career repercussions.)

On one occasion in the front office, Manny says, Merino became angry with the two black women working the front desk and muttered to herself: “Estas

“We were all afraid to lose our jobs,” he says.

In reality, employees had every reason to be worried about being fired. According to Seth Frohlich, a consultant who worked with the association in 2016, Aguero twice made negative comments about black workers.

After a master association meeting one day in 2016, Frohlich was part of a group that went for drinks at the Mondrian hotel next door, he says. At the bar, Aguero told him: “The staff is too dark. I want to make some changes.”

“I recall this specifically because I was so taken aback by the comment,” Frohlich said in a sworn deposition June 13, 2018. “I said to her, ‘You can’t state that. You’re not allowed to make that comment. It is inappropriate.'”

On another occasion, Frohlich and Aguero were walking past the front desk, where one or two dark-skinned maintenance workers were talking to the concierge.

“Again she made a comment to me: ‘That’s such a ghetto look. We need to make some changes,'” Frohlich said in the deposition.

Those kinds of dog-whistle comments were common, according to employees and residents. Crawford says some owners would call the front desk about black guests from the Mondrian, who often visited the Mirador to use the ATM, buy groceries at the convenience store, or cross the pool deck to access the Mondrian’s boat slips and Jet Skis.

“There was talk about getting rid of the building ‘riffraff,’ but when I asked, ‘Who are the riffraff?’ it would always be, ‘You know, the people who don’t belong,'” Crawford says. “I’m old enough and black enough to know ‘riffraff’ was a code word.”

That was far from the only racially tinged remark, though. The former property manager, Brown, says Aguero told her that one of the black employees looked “like a drug dealer.” In an email Brown sent to the board in June 2016 after returning from maternity leave, she expressed concerns about the exodus of black employees.

“As a longtime employee of the Mirador 1000, I have navigated through some difficult and uncomfortable situations, but I have never felt so disrespected, harassed, and bullied as I do by current members of the board of directors and those owners who are in their corner,” she wrote. “I feel there is some discrimination at play, as Mary who is black was forced to seek other employment, Ernie who was black was forced out, Amani who is black is being forced out, and now I feel like I am being forced out.”

Brown accurately predicted her own future: By that September, she too was gone.

“What happened here was a systematic forcing-out and termination of longtime employees,” he says. “People started to see. It was talked about in the building how all the black people were disappearing.”

Ross, who kept his maintenance job until early 2018, says it’s still difficult for him to articulate the discrimination he experienced firsthand.

“They knew how to say their words, but you could see it and you knew it was going on,” he says. “Every other week, we were losing a different person, and everyone that came in was a different ethnicity. It was different from the African-American [staff]. It was white, basically.”

Ayers lost her position at the front desk in May 2016 after a new property management company was brought in. After being summoned to Aguero’s apartment, where Aguero was drinking a glass of red wine, Ayers says Aguero told her the new company believed it was a conflict of interest for Ayers to continue working in concierge because she lived in the building. Weeks later, when Ayers attended a meet-and-greet with the new company, she says the company’s representatives told a different story.

“They said this is what Arianna had told them. They were following Arianna’s wishes, basically,” Ayers says.

(Fernandez, the attorney representing Aguero and Merino, declined to individually discuss the various allegations made by former employees and residents. Instead, he issued a blanket denial on their behalf and said he was “unable to go into any further details due to pending litigation.”)

“People saw, but the damage had definitely been done,” Shugarman says. “It went from being a real family atmosphere to being just really, really toxic.”

Valerie Crawford moved out of the Mirador 1000 after experiencing racial discrimination.

Courtesy of Valerie Crawford

In the aftermath of 2016, most residents at the Mirador avoided discussing the conflict between black employees and residents and the condo board. But for others, it wasn’t so easy. Valerie Crawford remembers cooking a tofu-and-quinoa dinner one night in the summer of 2017 when she noticed she didn’t have any broccoli. She put on her shoes and grabbed her bag to head to Whole Foods across the street, but when she reached her door, she hesitated. What if she ran into a hostile neighbor in the elevator?

“I thought, I don’t even have the energy and emotional bandwidth to go out,” she recalls. That night was the final straw – Crawford decided she had no choice but to move out of the building.

“That dinner was the dinner that said to me, If this is how you’re living, you’re not even living anymore,” she says.

A new board, which included Ayers as the vice president, was installed in January 2017. But Crawford says she and her neighbors never openly talked about what had happened the previous year. She was angry about not only the two board members who remained in the building as residents, but also what she saw as the inaction and apathy of almost everyone else who lived there.

“You all watched this, you all saw this, and you can’t go from that many black people working in that building to have it flip that much in one year, hear those comments, and not think that something is happening,” Crawford says.

“This is my home. I don’t know why I should let them run me off.”

“There was nothing I could do other than what I was doing [by] standing up to it,” he says.

Though the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has offered protections for employees against hostile work environments since 1964, it wasn’t until September 2016 that HUD formally adopted similar rules against “hostile-environment harassment” in private housing. In part, the new rules compel condo associations to intervene when residents are being threatened or intimidated based on their sex, religion, race, color, familial status, national origin, or handicap.

“The new regulations require the association to be an active participant to help stop the harassment of their residents,” says Marcus, the condo law expert from Boston. “They simply can’t ignore it.”

But none of the Mirador employees who spoke with New Times filed lawsuits against the association or complaints with the EEOC or HUD regarding discrimination. A few said they couldn’t prove why exactly they were treated so poorly, while others said they didn’t want to get involved in a court case. “It costs a lot of money to litigate and fight against something like this,” Shugarman notes.

He would know: In October 2016, he sued Merino, Aguero, Aguero’s husband, and the association for defamation. In his complaint, Shugarman says his fellow board members publicly accused him of stealing from the association, a charge he strongly denies. A judge dismissed the case in August, saying Shugarman failed to show those statements were published; Shugarman’s attorney has filed for a rehearing.

Crawford, who had an office at the Mirador for her real-estate business, filed a similar lawsuit against Aguero and the association in January 2017. Her complaint says Aguero made defamatory statements falsely accusing Crawford of inappropriate business relationships with former board members to make improper and illegal financial gains. Both Aguero and the association have denied those claims; the case remains open.

Though Crawford felt she had no choice but to leave the building, her former roommate Ayers has decided to stay – at least for now.

“Living in the Mirador right now… I do still feel that

Ayers says she wanted to share her story “not to cause a war” but “to ask people to be honest and open and real about racism.”

“Every single day, especially since Trump’s election, has been a hard day as a black person,” she says. “I think we’re a microcosm of this nation.”

Now more than ever, she thinks back to 1989, when she and Crawford moved into the building. Twenty-nine years later, it doesn’t feel like much has changed.

“I’m very comfortable in the white world,” Ayers says. “But I don’t think the white world is comfortable with me.”