Illustration by Brian Stauffer

Audio By Carbonatix

Kevin was home alone after school one day when two Mormon missionaries came to his doorstep. The 16-year-old opened the door and invited them in. The young men handed him some brochures and asked if they could pray for him. In the living room, they kneeled beside him, touched his shoulders, and asked if he felt the Holy Spirit. He said yes.

At the time, Kevin was a Jehovah’s Witness. He was used to being on the other end of the transaction – his childhood had been spent going door-to-door in the suburbs of South Florida, where most people politely ignored his knocks. While opening the door for the Mormons seemed like a common courtesy, Kevin was also curious to compare his beliefs to theirs.

At the end of the visit, the missionaries asked Kevin if he would like to be baptized. He told them he would think about it and asked them to return the next day. But when they came back the following evening, Kevin’s parents were already home from work. As they watched from the kitchen, Kevin told the missionaries that, no, he was not interested in their message.

“My parents didn’t want that,” he says today. “Witnesses, they feel like they’re the true religion.”

It was around that time that Kevin began investigating his own beliefs. He read Crisis of Conscience, a 1983 memoir by an ex-Jehovah’s Witness, and began watching videos from John Cedars, a YouTuber who left the religion as an adult. Kevin joined his school’s secular club and lurked on atheist forums on the internet. By the time he was 20, he no longer believed in the doctrine of the Jehovah’s Witnesses or in the existence of God at all.

But instead of leaving the religion, Kevin kept up appearances as a faithful Witness. Now in his early 20s, he attends twice-weekly meetings with his parents at the family’s Kingdom Hall and spends up to ten hours a month preaching door-to-door with other members of his congregation. If anyone found out he was secretly an atheist, he could be “disfellowshipped,” or expelled from the community and cut off from his parents.

“Basically, they would shun me if I spoke out against the religion or did anything wrong,” says Kevin, who asked New Times not to use his real name. “There is an obligation. You’re just as culpable if you don’t turn them in.”

Like Kevin, millions of Americans are now leaving the religions of their childhood. The latest Pew Research Center survey, from 2014, shows that almost a quarter of adults (22.8 percent) have no religious affiliation, an increase of almost 7 percentage points since the last survey in 2007. The vast majority of those people – 78 percent – say they were raised with religion but have since abandoned it.

“You can’t just force people to believe a certain way.”

Only 53 percent of those surveyed in 2014 said religion was very important in their lives, down from 56 percent. The rise of the internet, increasing rates of higher education, and clergy sex abuse scandals have all contributed to the country’s increased secularism, according to Pew’s research.

Despite those changing attitudes, American atheists remain an almost voiceless minority. In the United States, their population has barely budged – just 3.1 percent of adults identify as atheist, up from 1.6 percent in 2007. Some nonbelievers, including Kevin, have stifled their views to keep the peace with relatives. Many simply don’t care about religion one way or another, while others are confused about what exactly it means to be an atheist.

One obvious reason for the low numbers is that atheists have no recruitment strategy, no formal leadership, and, in many parts of the country, no community-level organization. There is no system of fundraising or tithing and, therefore, no budget. For some atheists, this lack of structure is a flaw, while for others, it’s a perk – whether atheists should band together as a united group is still the subject of some debate.

The atheist community has also struggled to combat the public perception that nonbelievers are immoral and self-righteous or generally unlikable. The fact that American atheists are overwhelmingly white and

But several South Florida atheists are trying to change that image while encouraging other nonbelievers to go public. Meetup groups in Miami-Dade and Broward have been building a highly engaged community with members who get together weekly or monthly. At the University of Miami, philosophy professor Anjan Chakravartty recently began his tenure as the nation’s first chair for the study of atheism. The position was funded by a $2.2 million endowment from Miami resident Louis Appignani, an atheist philanthropist who is throwing his fortune at the cause.

“If a major university is studying atheism, it gives us some legitimacy,” Appignani says. “I think one should feel proud that they’re an atheist, that they should feel good about

Research suggests this generation of college students is more receptive to that message than their parents or grandparents – 29 percent of younger millennials say they doubt or do not believe in the existence of God, a higher proportion than any other age group, according to the latest Pew survey. The question is whether they will embrace atheism and help rehabilitate its image or reject the label altogether.

“Religion is not going away, because people do see benefits,” Kevin says. “You have to prove things to them. You can’t just force people to believe a certain way.”

Elena Izquierdo became one of the organizers of the Miami Secular Humanism Meetup after growing up in the Pentecostal church.

Photo by Michael Campina

Inside a cozy, wood-paneled room at John Martin’s Irish Pub in Coral Gables, eight atheists sit at an isolated table in the corner. Four men and four women from the Miami Secular Humanism Meetup sip pints of Guinness and glasses of Chardonnay. As a waitress brings out platters of fish ‘n’ chips and bowls of French onion soup, the conversation turns to gender politics.

“I stopped caring about where the atheist community was going online years ago because I sensed all this toxicity there,” says Eduardo Pazos, one of the meetup’s organizers.

“You mean with misogyny?” asks Elena Izquierdo, another of the group’s leaders.

“Yeah, lots of misogyny, lots of Islamophobia, a lot of other toxic elements,” Pazos says.

“We need more atheists to look up to,” member Galia Ofer interjects. “We don’t have enough of them.”

Controversies within the atheist community have almost certainly contributed to its low numbers. Nationwide, women and people of color remain a minority among atheists, and problematic figureheads such as Richard Dawkins seem to be regularly embroiled in accusations of bigotry and misogyny. In the Miami metro area, the Pew survey shows that only 3 percent of the population is atheist- someone who does not believe in God or the afterlife. Another 3 percent identify as agnostic, meaning they don’t believe or are skeptical about the existence of God but can’t say for certain.

Izquierdo, a 45-year-old third-grade teacher, grew up Catholic, attending mass just a few times a year for special occasions such as Christmas and Easter. When she was 12, her parents began going to a Pentecostal church in Miami where congregants spoke in tongues and services often lasted three hours or more, she says.

As a teen, Izquierdo taught Sunday school and attended summer camp but always had her doubts.

“I remember I was like 15, telling the camp counselor I didn’t understand why I never fell back when people laid hands on me or why I didn’t speak in tongues,” she says. “I felt like something was wrong with me.”

Izquierdo continued going to church until her early

“I couldn’t stand it anymore,” Izquierdo says. “When I started my real questioning – my real, real questioning – it was a house of cards.”

As a woman of Cuban descent, Izquierdo doesn’t look like most atheists, who tend to be white and male. Like the other members of the Miami meetup group, she has been critical of famous atheists such as Real Time host Bill Maher, whom she stopped watching after he re-created a photo of Al Franken groping a sleeping woman’s breasts.

“It is a shame that he does have great guests and he does have, for the most part, progressive ideas,” Izquierdo says. “But you have to weigh those things out, and, I’m sorry, I’m not going to reward that kind of behavior just because he’s an atheist.”

Dawkins, a British evolutionary biologist who is one of atheism’s most prominent voices, is another figure who’s been at the center of many scandals within the community. The 77-year-old has routinely made provocative comments about Muslims, including in an interview where he called Islam “one of the great evils of the world.” In January 2015, he received more blowback after tweeting, “Of COURSE most Muslims are peaceful. But if someone’s killed for what they drew or said or wrote, you KNOW the religion of the killers.”

Women have also been offended by Dawkins. In a 2011 incident that became known as “Elevator-gate,” he publicly mocked Rebecca Watson, a respected blogger

“We do seek to normalize atheism and destigmatize it.”

Other celebrity atheists, including podcast host Sam Harris and the late author Christopher Hitchens, have faced similar criticism for their comments about Muslims and women. And those kinds of remarks aren’t coming only from the top – online atheist communities are notoriously rife with demeaning comments. In 2015, the /r/atheism subreddit was ranked the third most toxic on all of Reddit.

Atheism also has a race and ethnicity problem. Just 3 percent of atheists are black; only 10 percent are Latinx, according to Pew’s research.

“There is a huge sense of disconnect that many people of color feel,” says Mandisa Thomas, who founded the nonprofit Black Nonbelievers in 2011. “That is changing, and there are more organizations and people recognizing it, though there is still a long way to go.”

Thomas, who lives in the Atlanta suburbs, grew up nonreligious but says she didn’t identify as an atheist until 2010. For her, connecting with other black atheists seemed almost impossible, and understandably so – 97 percent of black Americans say they believe in God, the highest proportion of any racial group.

“The identity of atheism is still seen as white, so there is an institutional apprehension to identifying as atheist,” Thomas says. “If you are black and atheist, you risk being seen as a race traitor.”

As one of the most public faces of black atheism, Thomas has spoken at numerous events and conferences, although she is still confronted by the occasional racist comment from white attendees. After she gave a talk in 2013 about what the secular community could learn from the hospitality industry, a white woman asked her what she planned to do about “black-on-black crime.”

“Some people tried to say it was oblivious, but, no, it was racist,” Thomas says. “Their notions or their perceptions of the black community still tend to be very, very skewed.”

Now in its seventh year, Black Nonbelievers has 13 chapters, including one in Orlando. In late November, the organization sailed out of PortMiami on its second-annual Convention at Sea. With more than 3,000 members and subscribers across the nation, the group aims to be an accepting, welcoming community that allows black atheists to disassociate themselves from religions in which they no longer believe.

“We want to say, ‘Hey, if you thought you were the only one out there, there are more of us, and we are here for you,'” Thomas says. “We do seek to normalize atheism and destigmatize it, and one of the ways to do that is to be out.”

Anjan Chakravartty recently started his job as UM’s chair for the study of atheism, humanism, and secular ethics, the first position of its kind.

Photo courtesy of Anjan Charkarvartty

As the sun sets over Coral Gables, Professor Anjan Chakravartty stands at the front of a conference table in a cramped classroom at the University of Miami. Dressed in shirtsleeves and dark-wash jeans, he addresses students by their first names and takes periodic sips of coffee from a black Star Wars mug.

It’s the last regular class of the semester for Chakravartty’s course on science and humanism, a belief system that rejects religion in favor of logic and reasoning. Wasting no time, he strikes up a discussion about how science should inform public policy.

“If we’re not going to use something spiritual or religious to serve as a guide for how we should live individually and how we should live collectively, we might want to rely on something else,” he says. “And the standard move is to say, well, what we should rely on is our best science.”

Chiming in, his students bring up pitfalls – namely, junk science and bad actors who manipulate data for political gain.

“Making policy on the basis of our best science for what we should do and how we should behave,” Chakravartty responds, “turns out to be really complicated and messy.”

In July, the Canadian-born professor began his tenure as UM’s chair for the study of atheism, humanism, and secular ethics after five years in the philosophy department at the University of Notre Dame – a Catholic school. The position, funded through Louis Appignani’s $2.2 million

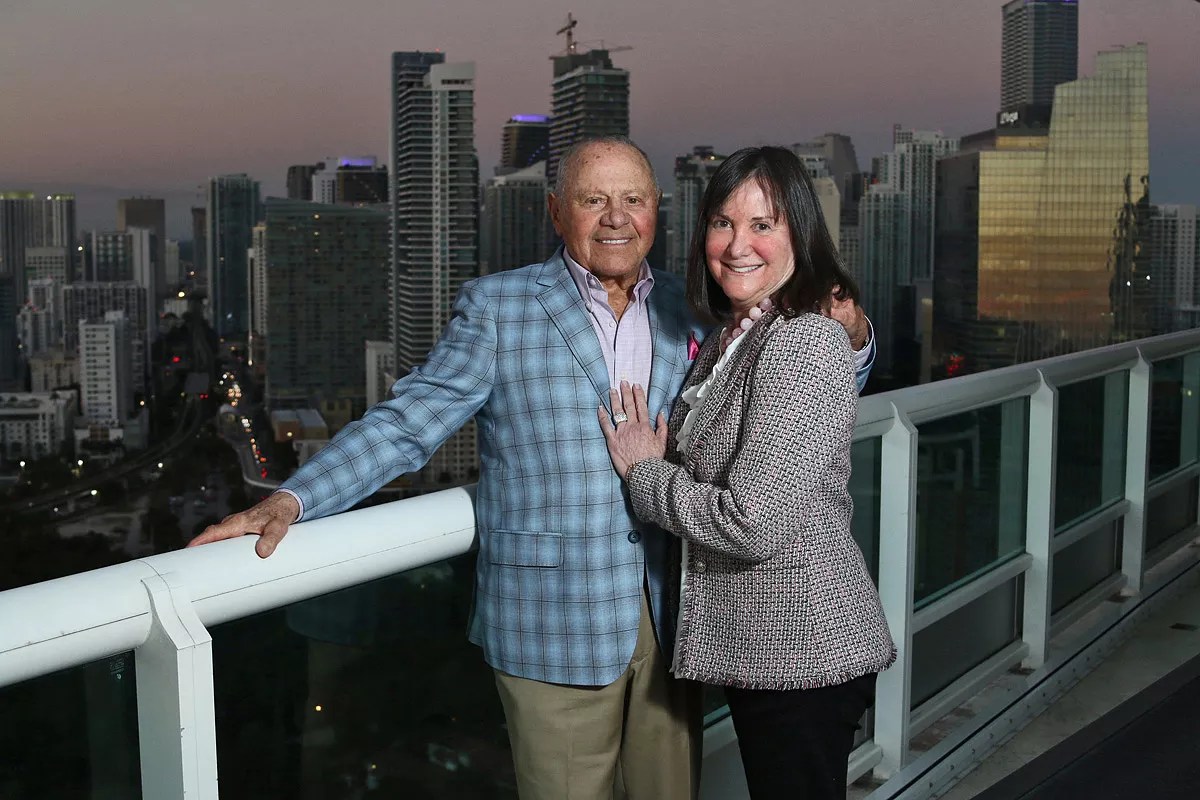

“I think what we’ve done at the University of Miami will have an impact across the country in subtle ways,” says Appignani, a Brickell philanthropist who made his fortune as president of the Barbizon modeling school. “We’re not proselytizing, but we just want to be on equal footing with every other philosophical way of thinking about life and death and the afterlife.”

Though Appignani has made a point of broadcasting his views, Chakravartty shies away from questions about his own beliefs.

“I don’t want students to say, ‘Oh, Chakravartty has this view- I better make sure I don’t say anything bad about that view,'” he explains. “It’s irrelevant what I think.”

Chakravartty was raised by immigrant parents in a small town outside Toronto. In India, his family had belonged to the elite Brahmin caste at the top of the hierarchy. He says he grew up listening to his Hindu father reciting Sanskrit mantras that, to Chakravartty, were incomprehensible. It wasn’t until he was about 12 years old that he began asking questions about his dad’s faith.

“It turned out that my father doesn’t really believe in any of these things,” Chakravartty says. “For him, it was just something that you did as part of a membership in a community.”

Brickell philanthropist Louis Appignani and his wife Laurie recently funded a chair for the study of atheism at the University of Miami.

Photo by Michael Campina

In his new role, Chakravartty isn’t interested in revisiting the debate about whether God exists, he says. Instead, he wants his students to explore the history and philosophy of atheism and what it means to ascribe to a worldview void of religion.

“It’s a chair ‘for the study of,’ and I actually think that’s really important,” he says. “If it were a chair for atheism, that might give the mistaken impression that it is an advocacy position.”

Like Chakravartty, Appignani was raised in an immigrant family where religion was important culturally, if not personally. Born in the Bronx to Italian parents, Appignani was educated in Catholic schools and spent his Saturday nights in confession and Sunday mornings at mass.

“It was like a tradition,” he says. “I never really was tied into it. It was just there, and that was what you did.”

Shortly after he began studying accounting at the City College of New York, Appignani discovered the work of Bertrand Russell, a British philosopher who wrote books and essays with titles such as “Why I Am Not a Christian.”

“I thought, Yeah, this is the way I think,” Appignani says. “Maybe I’m not so far-out.”

“This is where the world is going, whether you like it or not.”

Although he privately identified as an atheist, Appignani participated in the Newman Club, a social group for young Catholics, he says. At one point, he even campaigned to be the club’s president but ultimately lost the election to his best friend. “I just kind of played the game, like politicians do today,” he says, laughing at the memory.

After college, Appignani worked as a management consultant and started a chain of computer programming schools before buying out the founders of Barbizon in 1962. When he retired in 2000, he knew he wanted to use his wealth for philanthropy and decided to enter uncharted waters. In 2001, he launched the Appignani Foundation with the goal of replacing faith-based ideology with reason and science.

“Starving people and the homeless – everybody is doing that,” he says. “I found something that no one else was doing, and I really felt committed to it.”

He had been in talks with UM about creating a chair of atheism for more than 15 years but says the decision-makers were hesitant to use the word “atheism” in the title. Before finally reaching an agreement in 2016, the school tried to persuade him to use the phrase “philosophical naturalism” instead, he says.

“I had to negotiate about a year with the university, that you’re not getting my $2 million unless this is for atheism. If you call it naturalism or something like that, I’m not going to do it.”

Now that the chair is a reality, Appignani says he has stepped back and allowed Chakravartty and the university to set the agenda. In his mind, the position puts the country one step closer to an “inevitable” future where atheists can publicly identify themselves without consequence.

“This is where the world is going, whether you like it or not,” he says. “I like it.”

Eduardo Pazos, an organizer for the Miami Secular Humanism Meetup, has been critical of Islamophobia and misogyny within the atheist community.

Photo by Michael Campina

Inside a sanctuary at Lynn University in Boca Raton, a Muslim, a rabbi, a Hindu, an evangelical Christian, and an atheist took turns sharing their views on the afterlife. The February

The Muslim talked about the body

The rabbi spoke of every moral human reaching “the world to come.”

The Hindu explained the theory of reincarnation.

The evangelical referenced the words of Jesus, who told his followers: “No one comes to the Father except through me.”

Then the atheist stood.

“Atheists believe that the same thing happens to all of us when we die: We stop living, and that’s it,” said Jim Scott, a member of Florida Atheists and Secular Humanists (FLASH) in Palm Beach County. “There’s no evidence for

For Scott, the vice chairman of FLASH, making regular appearances at interfaith events is one way he is actively trying to normalize atheism to a still-religious general public.

“The term ‘atheist’ has such a negative connotation,” he says. “They think being an atheist means you eat babies and worship the Devil.”

Like Scott, many atheists are becoming more vocal, fighting fire with fire by sharing their views with an evangelical fervor. In the absence of a church, groups such as FLASH are expanding across South Florida to unite a community of like-minded atheists and agnostics.

“It’s more defensive than offensive,” Scott says. “When we have legislators try to pass laws based on the Bible, then

Appignani, the Miami philanthropist, is also of the mindset that atheists can best achieve equality by outspokenly demanding it. In 2006, he launched the Appignani Humanist Legal Center, which employs a staff of attorneys that

“I feel very good about the impact it’s had,” Appignani says. “I think we’re making a movement.”

In Miami, the Secular Humanist Meetup has been around for more than 12 years and has almost 500 members. When Izquierdo, the third-grade teacher, joined in 2011, she was tired of her Pentecostal friends dismissing her questions about the faith with platitudes like “God has a plan.” After her first meeting with the secular group, she felt like she had finally found her tribe.

“It was incredible to be able to speak to people that had answers, that had read things,” she says, “to not have somebody say, ‘Oh, you have to have faith, and you have to believe.'”

“They think being an atheist means you eat babies and worship the Devil.”

As one of the group’s five organizers, Izquierdo helps plan book clubs, lecture series, film showings, and other events. Some members have suggested starting a local chapter of the secular Sunday Assembly, a global initiative to create “church without God.” Though Izquierdo gave her blessing, she herself has no interest in getting involved or helping to organize those kinds of services.

“That’s one of the things that I don’t miss,” she says. “I personally do not need to go to the same place for the same amount of time with the same amount of people to talk about the same shit every single Sunday for an hour. I have no interest in emulating religion in that shape or form.”

Chakravartty, the UM professor, has a similar philosophy.

“I don’t think we need to replace religious communities with nonreligious communities,” he says. “For a lot of people, it’s just irrelevant. It’s not something that they are interested in or

But for people just beginning to untie themselves from religion, local atheist groups are a safe space to learn more about what it means to live in a world without God. For the past three years, Kevin has secretly gone to South Florida meetup events to connect with other people who have left their religions.

“I was looking forward to the meeting every week because it’s just like friendship, basically,” he says. “It’s kind of the same thing as being a Witness with the Kingdom Hall, but it’s less formal, it’s less pressure, it’s not obligatory, but you have the community aspect of it.”

Although he has told his parents he no longer believes in God, they have not yet kicked him out or reported him to the elders. For now, it’s a relationship in limbo – Kevin respectfully tries to persuade his parents to abandon their religion, while they gently nudge him back toward it. The best-case scenario, one where he can live openly as an atheist without being shunned by his family, seems like an idealistic hope, requiring faith he no longer has. Someday he knows he will have to choose between his parents and his inner convictions.

“Eventually, it’s just gonna hit the fan, and I’m probably going to have to make the decision,” Kevin says. “When I was 16, 17, it really affected me, but I feel like I’ve moved on emotionally. I’m just ready for the consequences.”