Audio By Carbonatix

School looks quite a bit different this year for Ashley, a high school English teacher with Miami-Dade County Public Schools who is in her second year of teaching.

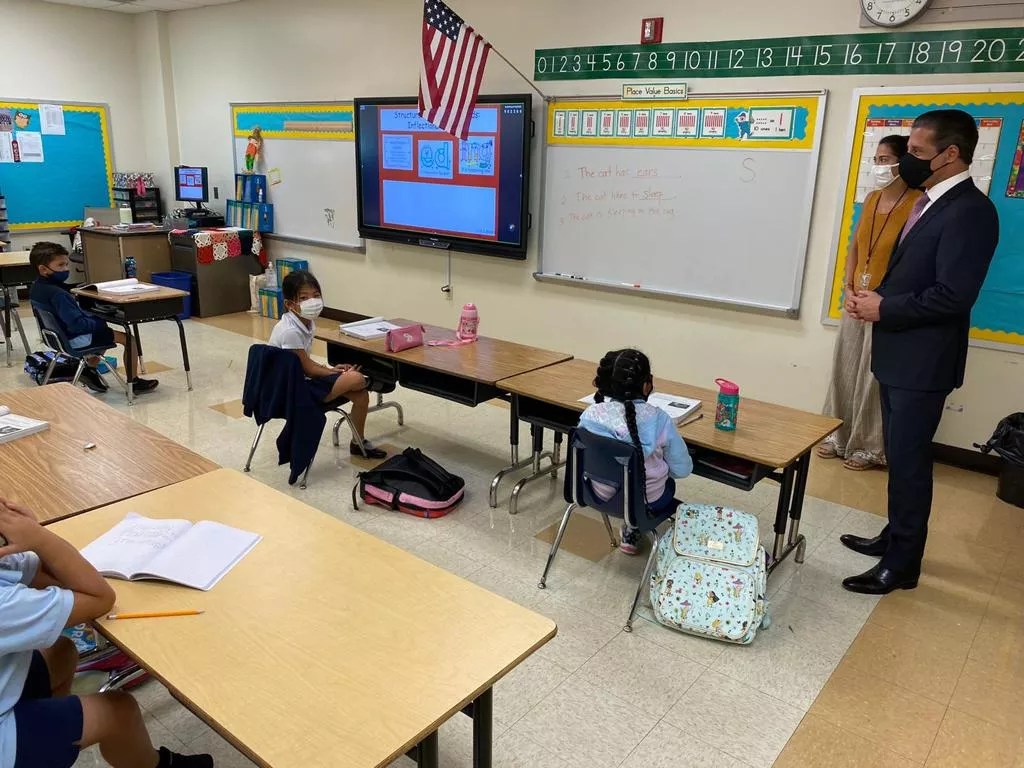

Her students sit at socially distanced desks in her classroom and log onto Zoom, joining students who sign in remotely from home. Ashley sits behind a plastic shower curtain at her desk and teaches her lesson from there. The quality of instruction is the same with dual-modality because all of the students are following along via Zoom, even though Ashley is only six feet away from those attending in person.

But Ashley tells New Times she feels hamstrung by the teaching method, which she believes is ineffective. In a survey she sent to her students last week, one responded that teachers don’t pay attention to the kids on Zoom once they have kids in front of them in the classroom.

“If a kid can notice that,” Ashley says, “why can’t admin or counselors?” (Ashley, like the other teachers quoted in this story, asked New Times not to use her real name because of possible job repercussions.)

Last week, more than 140,000 students returned to schools for in-person learning under pressure from the state. A potential loss of up to $300 million in school funding nudged school-board members to reopen on October 5 instead of October 14.

The decision has come under scrutiny now that two employees and 14 students have tested positive for COVID-19. Some schools are already backtracking: Coral Park Elementary in Westchester closed its campus and moved to online-only instruction yesterday, after one employee and three students tested positive for the virus. The school reopened this morning.

The school board, meanwhile, has been accused of hypocrisy: While teachers have been made to return to campus, the school board continues to hold its meetings remotely.

Beyond concerns about the virus spreading, teachers have been frustrated by what they say is a lack of communication from the top down. Ashley says she heard about the board’s decision to reopen schools from the #TeamMDCPSTeachers Facebook group rather than directly from school administrators or board members.

“That’s not how I should be hearing about it,” she says. “As a teacher, I should be told exactly what the board decides.”

Jennifer, who teaches third-grade, agrees that the stress of reopening was intensified by a lack of clarity from the administration. She says that during a faculty meeting, she posed specific questions about the logistics of bathroom breaks and seating arrangements. She says her school’s administrators suggested she make those logistical decisions “at her own discretion” and told her not to worry because “kids will do exactly what you tell them to do.”

She contemplated leaving the profession entirely.

“It felt like we were these guinea pigs in an experiment,” she says. “Whatever the intention was behind reopening, it wasn’t the students.”

District spokesperson Jackie Calzadilla tells New Times that all decisions have been communicated clearly to teachers, adding that Superintendent Alberto Carvalho sent a letter to employees the day the reopening was announced. In addition to the district’s efforts, she says, schools are communicating directly with teachers through various means.

Jennifer says she was eventually assigned to an online classroom. She now teaches all core subjects – including reading, writing, math, science, and social studies – to 26 students who opted for remote learning. Since last week, there have been many last-minute changes, including a new schedule with an almost entirely new roster of students and a new subject area for her to teach. Regardless, she is grateful. She reports to her classroom daily but teaches to a roomful of empty desks.

“It felt like a relief,” she says of being assigned to the remote group. “But there was also guilt. What about [the other teachers on] my team? What about their families?”

Even with those challenges, she is determined to do the best she can. Teaching a class entirely online requires different preparation, but she has experience teaching students remotely.

“I tell my students we can do hard things,” she says.

The teacher’s union, United Teachers of Dade (UTD), has been adamantly against dual-modality since the start of the school year. A letter of understanding drafted between UTD and the district clearly states that dual-modality is not required of teachers. Yet since schools reopened, some teachers say they have been pushed to deliver simultaneous online and in-person instruction.

UTD president Karla Hernandez-Matz wrote in an email to principals last week that “all research indicates that working with both modalities promotes ineffective instruction for both sets of students” and “these scheduling issues should be resolved immediately.”

But Ashley tells New Times the pressure to teach dual-modality in her case came directly from her school’s union rep. The week before schools reopened for in-person instruction, Ashley says she got a call from her school’s scheduling counselor, who happens to be one of the union stewards on campus. She says the counselor tried to persuade her to teach remote and in-person students simultaneously. When Ashley said she preferred not to, she was told her decision could result in an increase in her class sizes or an extra class period.

“I felt guilt-tripped and harassed,” Ashley says.

According to Ashley, teachers in other departments at her school received similar calls. She says the counselor told one math teacher that keeping the schedules as they were would “make her job a lot easier.”

“What about our jobs?” Ashley counters.

Other teachers in the district are concerned about their schools’ ability to abide by district safety guidelines. Several teachers at a Miami elementary school tell New Times that there was no soap in the bathrooms last week and that classrooms were left dirty over the weekend. Teachers had to clean their desks themselves. There was also overcrowding both inside and outside the building during dismissal, with students rubbing against each other inside and parents standing in a tight line outside as they waited for their kids to come out.

That elementary school is also experiencing a teacher shortage. According to one teacher, the district is deploying underqualified personnel to fill the gaps. This week, a high school counselor was sent by the district to teach third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade Spanish in person. She had been deployed to a middle school the previous week. It was unclear whether or not she’d stay at the elementary school.

The general consensus among the five teachers who spoke with New Times is that they’ve been kept in the dark since the beginning of the school year and forced to shoulder the burden of many responsibilities that district decision-makers are less exposed to. Younger teachers like Ashley face pressure to take on more responsibility because they’re newer to the profession.

But even those who have been in the system for decades say the district continues to make them feel undervalued. One veteran teacher says nothing would change if she chose to quit.

“They don’t care. They know that we’ll be replaced,” she says. “They’re not going to care that they’re losing a good teacher.”