U.S. Attorney’s Office

Audio By Carbonatix

At a dilapidated Knights Inn in Homestead, Almlak Benitez stood in front of a camera with a black mask covering his hazel eyes and a long robe obscuring his tattooed biceps. Cockroach carcasses lined the worn-out carpet of the $69 room, which he and his friend Mohammad Skaik had pooled their money to pay for. A rank smell hung in the air, and to make matters worse, they’d been forced to shut off the air conditioning to get better sound for their video.

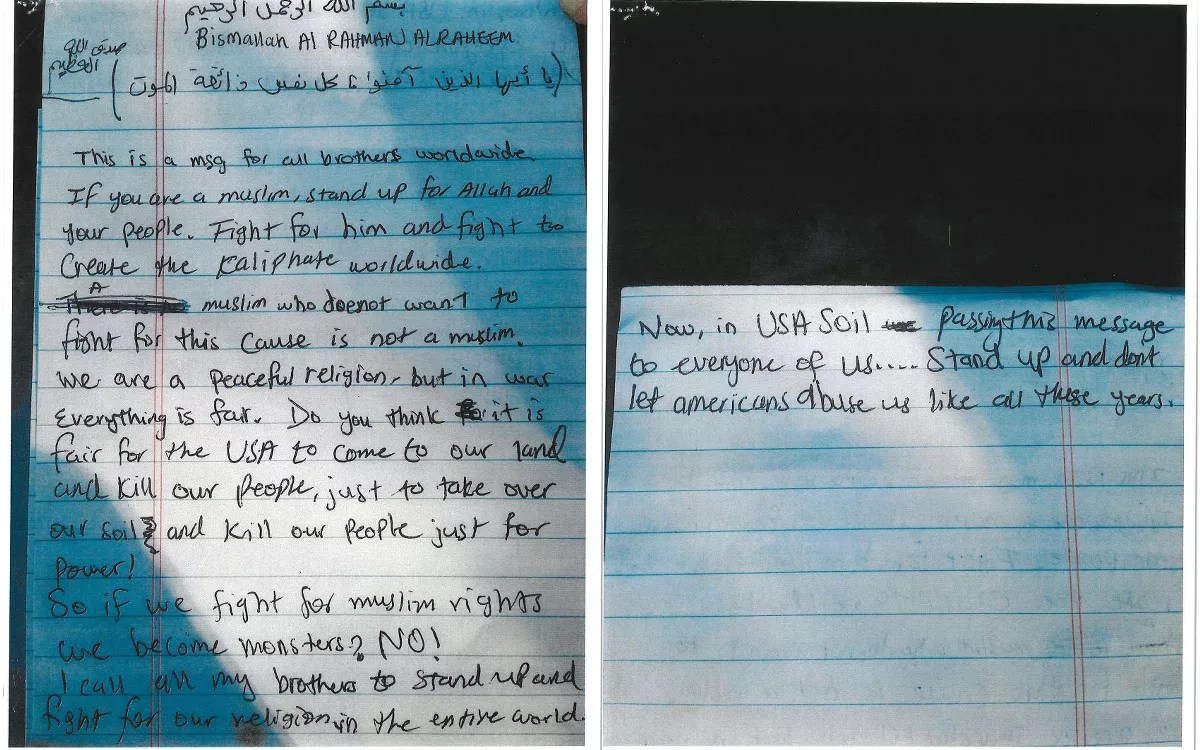

Nevertheless, they’d decided to suck it up until they got at least one good take for YouTube. From behind the camera, Skaik signaled with a thumbs-up that he was ready. Benitez clutched his script and began: “In the name of God, the most – uh, wait, hold on. Fuck!”

Flustered, he started over.

“In the name of God, the most merciful, this is a message for our brothers worldwide. If you are a Muslim, stand up for Allah and our people. Fight for him and fight to create the caliphate worldwide,” he recited. “Muslim who doesn’t want to – fuck. Wait. Hold on. Oh, fuck!”

For at least a year, Benitez had been mesmerized by recruitment videos for the Islamic State, but starring in one was an altogether new experience. As the day wore on, he grew more self-conscious as he stumbled through one take after another. Playing back the recording from his first few tries, he could hardly listen to himself.

“Fuck, my voice,” he said. “Let’s do it again.”

By the time the afternoon was over, the two friends had filmed ten takes in English and one in Spanish. Skaik pledged to edit the clips so they looked just right. Once it was done, they planned to show the final product to a guy in Boca Raton who seemed like a promising recruit.

“Just show him the video and be like, ‘This is what we’re doing, and if you want to be a part of that, come to the team,'” Benitez told Skaik. “Tell him, like, we ain’t lone wolf… What we’re trying to do is get more people.”

As they left the seedy motel May 23, 2015, the two made plans to meet up later that week. But beneath their easy rapport, each was hiding something from the other. Benitez’s name was actually Harlem Suarez, and he’d been brought up Catholic by Cuban parents who’d immigrated to the United States when he was 12. Far from the fierce Islamic warrior he longed to be, in real life he worked as a cook at a French crepe restaurant in Key West and partied on Duval Street like any other 23-year-old.

“Tell him, like, we ain’t lone wolf… What we’re trying to do is get more people.”

Skaik, meanwhile, had an even bigger secret: As a native Arabic speaker, he’d gone from a stint in the U.S. military to serving as a paid informant for the FBI. Two months after filming the video at the roach-filled motel, Suarez would be hauled off to jail and accused of planning to murder scores of tourists by bombing a public beach.

The FBI announced the case with fanfare, releasing a report quoting Suarez saying he wanted to “cook Americans.” Monroe County Sheriff Rick Ramsay told reporters that Skaik and the feds had stepped in just in the nick of time.

“He was serious and was really trying to become a player and set himself out to get noticed by ISIS,” the sheriff told the Key West Citizen. “He wanted to be the real deal. I’m convinced if he had the ability, he would have.”

But the story of Suarez’s path from Cuban immigrant to wannabe ISIS soldier is more complicated than prosecutors have let on. Two years after the arrest, many of his closest friends and family members still believe he was entrapped by the FBI. They insist Suarez is a naive, emotionally stunted young man who pledged allegiance to ISIS only after the feds repeatedly pushed him to do so.

“What they did to him was shit,” family friend Ruben Sanchez Cruz says.

Their protestations aren’t just wishful thinking. Since 9/11, the FBI has aggressively used confidential informants like Skaik to push confused wannabes like Suarez over the edge just to score easy points in the endless War on Terror, critics say. A disproportionate number of those cases have happened in the Sunshine State: Since the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon 16 years ago, the Department of Justice has charged 67 Floridians with terrorism-related crimes, more than any other state but New York.

Suarez’s unusual tale shows both the lengths the FBI will go to make terrorism arrests and exposes just how vulnerable aimless, impressionable young men can be to the overtures of violent extremists.

“The question is whether we’re using counterterrorism to actually identify terrorists,” says Michael German, a national security scholar and former undercover FBI agent, “or trying to find gullible young people to coax into a manufactured plot for the purposes of scoring a win.”

Unaware that the FBI was onto him, Suarez wrote a script for an ISIS recruitment video with an undercover informant.

U.S. Attorney’s Office

Suarez came into the world choking. As his mother went into labor at a Cuban clinic in September 1991, the umbilical cord wrapped around her baby’s neck, nearly suffocating him.

“He was born black,” she later told a court-appointed psychologist.

The newborn spent three days at the hospital before coming home to his parents, Vilma Quintana and Bernardo Suarez. The Catholic family lived in Las Cruces, a midsize commercial city at the center of the region’s sugarcane and tobacco fields.

Growing up, Suarez was shy around girls and had a hard time relating to his classmates. He was trusting to a fault, believing well into early adolescence that the Smurfs and other cartoon characters on his TV screen were real. Later in life, an IQ test would put him in the low-to-average range.

“He was always taken advantage of by his peers,” his mother told the psychologist. “He was very gullible.”

In 2004, the family received a life-changing letter in the mail. With news they’d won the Cuban immigration lottery, known as el bombo, they moved to Florida and began a new life in Key West.

As a 12-year-old immigrant in his new public school, Suarez knew almost no English. In Cuba, he’d advanced to the ninth grade, but in the Keys, he was placed alongside sixth-graders at Horace O’Bryant Middle School. Though plenty of other Cuban kids filled the classrooms, the teachers weren’t always patient with native Spanish speakers.

“They don’t take their time to teach, you know?” Suarez would later explain in FBI recordings. “They just, you know, show the class and… you have to learn by yourself.”

At Key West High, he continued to struggle with classes and developed alarming habits, including cutting himself with a shaver. After the tenth grade, he dropped out of school and became a busboy.

“He was always taken advantage of by his peers,” his mother said. “He was very gullible.”

Over the next few years, Suarez bounced from job to job, stocking shelves at Kmart and scooping ice cream at Häagen-Dazs. In December 2013, he found work at the Key West International Airport cleaning planes and lugging baggage for an American Airlines contractor.

It was there that Suarez reconnected with Milas Leconte, a high-school classmate he’d known but never really talked to. Suarez was quiet back then, Leconte says, but as the two began spending shifts together, he realized Suarez was actually pretty cool.

“He was funny, like F-U-N-N-Y,” Leconte says. “He could really make you laugh.”

Among Suarez’s notable quirks were bold ambitions that bordered on grandiose. He’d spend his paychecks on iPhones and Armani clothing, bragging that soon he’d have a Rolex. Despite making $9.70 an hour, he was sure he’d someday be a millionaire.

“He’d tell me like how he was gonna be a famous musician, and I’d be like, ‘Man, you don’t even play guitar,'” says Leconte, who took most of what Suarez said with a grain of salt. “He never really had a construct of how to achieve anything. He just knew he wanted to get to the top.”

But behind his braggadocio, Suarez had a sweet, almost childlike disposition. He seemed confused, even offended, when people around him acted selfishly or treated others with disrespect.

“You could tell he was raised by good people,” Leconte says. “Because he was raised that way, he expected other people would be that way.”

Although he still shared an apartment with his parents in Stock Island, a working-class area just north of Key West, Suarez had a seemingly normal social life, zipping off on his scooter to head to the gym or meet friends for drinks on Duval Street. He dated his high-school girlfriend for six years, a time she later called “the best years of my childhood life.” But before their seventh anniversary, Suarez broke it off, telling her his mother didn’t want them together.

In his early 20s, Suarez struggled to figure out who he was. He obsessively tried on new personas, fantasizing life as a gangster, a powerboat racer, or a drug kingpin, his parents told the Miami Herald. Once, he bought himself a gold grill and started growing out his hair for dreadlocks.

“He is very curious to the extreme,” his mother told a court psychologist. (Suarez’s parents declined to speak with New Times for this article.)

In March 2015, Suarez lost his job at the airport after deploying an emergency slide while cleaning one of the planes. By then, Leconte had started working for the city’s public works department. The two stopped talking as frequently, though they still went out together every now and then on Duval. Even then, nothing about Suarez seemed off.

“He wasn’t a bad guy,” Leconte says, “but what happened says otherwise.”

Suarez was arrested by the FBI after leaving an undercover agent’s car with a backpack bomb.

U.S. Attorney’s Office

Sometime in early 2015, Suarez pulled a black knit mask over his face and tightened a bulletproof vest around his waist. Standing in front of his bedroom closet, he held up his right hand and pointed his index finger to the sky.

The wannabe gangster and multimillionaire had found a new identity to cling to: Islamic jihadi. Posted on his Facebook page, where he used the name Almlak Benitez, the dimly lit selfie sat alongside status updates where Suarez eschewed the traditionally peaceful tenets of Islam and threatened his followers with violence.

“Convert to muslim or be ready for the other world where you not going to be alive,” he wrote that April.

One post at a time, the page helped Suarez shed his identity as a goofball slacker and take on the role of a radical. Though the exact origins of his recruitment are still hazy, interviews and court records make clear that sometime between the spring of 2014 and early 2015, Suarez discovered the internet chatrooms and bloody ISIS videos that have inspired other attackers. By the end of the summer, it would cost him his freedom.

Growing up in Key West, Suarez knew only a few Muslims in real life. One of his co-workers practiced Islam, and his older sister in Houston had converted years earlier. But like hundreds of other Islamic State recruits in Florida and across the United States, most of his information came from the internet.

The web was a fertile ground for emotionally immature young men like Suarez to explore all kinds of fanatical ideas. Over the past decade, ISIS’s increasingly adept use of social media – including using Twitter to connect Americans with “virtual coaches” on encrypted messaging apps – has put its agenda in front of countless curious young men.

“The message isn’t tailored solely to those who are overtly expressing symptoms of radicalization,” then-FBI Director James Comey told the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs in 2015. “It is seen by many who click through the internet every day.”

Computer searches later showed that Suarez was flirting with radical Islam as early as April 2014. Four months after starting his job at the airport, he began Googling phrases such as “islam” and “musulman velo negro” – Spanish for “Muslim black veil” – as well as more alarming topics such as “how to make a bom [sic]” and “how to make a real grenade.” In September 2014, he searched for “isis map,” “black islamic flag,” and “muslim flag,” and in October, “isis tshirt,” “isis product,” and “isis flag white house.”

As he learned more about the Islamic State, Suarez tried to broach the subject with his older sister, who apparently warned him to steer clear.

“That’s not what it is… We don’t make wars,” she told him. “Muslims, they’re not supposed to be killing anyone.”

Suarez ignored his sister’s advice. On Facebook, he posted beheading photos and sent a blizzard of creepy recruitment messages to people he’d never even met. Most of the time, no one responded, but on April 15, 2015, a message came to his inbox from a young Palestinian guy in West Palm Beach named Mohammad Skaik. Suarez didn’t reply, but nine days later, Skaik sent another message.

“Hey Brother, Alsalamualaikum,” Skaik wrote, misspelling the Arabic phrase for peace be with you. “A word of advice, I’ve been down your alley and got my account taken down numerous times. I would be very careful not to post things unto my account relating to my location… Hope to get to know you.”

Suarez still didn’t respond, so ten days later, Skaik sent the same message again. This time, Suarez wrote back.

“Good to meet you my account was taken more then [sic] 4 times already but i still created then [sic] back,” Suarez replied. “How can we know each other?”

Their conversation on Monday, May 4, 2015, lasted until nearly 1 in the morning. In Skaik, Suarez found a true believer and someone to confide in about his latest obsession – a person who could help him find a higher calling in life. In the hour-and-a-half-long online chat, the two bragged about their guns and talked about training to become ISIS fighters.

By the end of the week, Skaik was so eager to meet up that he told Suarez he’d make the five-hour drive from his home in West Palm. That Friday, the two met for the first time in the parking lot of a waterfront Benihana in Key West.

Suarez and Skaik spent hours getting to know each other that day. Despite living in the Keys for almost half his life, Suarez said he still thought of himself as Cuban, not American. After watching the news more closely, Suarez said he’d grown increasingly critical of the United States, especially for the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

“I mean, this country have everything, whatever you want,” he said, according to FBI transcripts. “Why you wanna go to another country and start fight?”

Suarez had a new idea: detonating a bomb at a public beach in the Keys.

Eventually, the conversation turned toward more concrete action. After mentioning his plan to stock up on ammo, Suarez brought up the idea of explosives. He told Skaik that once they figured out how to make timer bombs, it would be easy to incite a panic.

“We can go to the Dolphin Mall in Miami and put like five of those” in the parking lot, he suggested. “We are letting them know that we ain’t playin’ around.”

But that wasn’t his only idea. Over a chicken quesadilla and a plate of fries at Denny’s, Suarez said cops were an obvious target, though you had to be prepared for the police to return fire. “But if we have grenades, we can start throwing grenades at them. They’re done,” he reasoned.

Before the end of the night, the two walked to the airport, where Suarez thought about how to plan a sniper attack from some nearby trees with a .22 rifle.

Over the next three months, the two continued to meet up to hatch plans together. On May 15, Suarez and Skaik scribbled down the script for their ISIS recruitment video at a Key West Burger King and regrouped in Homestead the next weekend to film it at the Knights Inn. Soon Skaik was introducing Suarez to a guy named Sharif, who said he could help them get explosives. After weeks in conversation, all of their talk was finally turning into a real plot.

In early June, the three met at the Banana Bay Resort, a Key West hotel with a topless-optional pool where Suarez liked to use the gym. Suarez had a new idea: detonating a bomb at a public beach in the Keys. He proposed filling a milk jug with nails and gasoline and connecting it to a cell phone so he could blow it up from afar. But Sharif said it wasn’t that simple. He bragged that he knew some guys who could help Suarez get what he needed.

“Well, brother, listen, before you start… let me talk to my connections, OK?” Sharif said.

And he pointed out that the plan still needed structure. When did Suarez want the attack to happen? How many people did he want to kill? With some prodding from Sharif, Suarez agreed that a Fourth of July attack sounded good. He had no thoughts on the number of victims.

“Like I said, uh, for me, I really don’t care like who’s the target, no. For me, anyone is the target,” Suarez answered.

But for some reason, his plans for an Independence Day attack fizzled. On July 6, he told Skaik he’d “been lazy… you know, working and working.” On July 11, he claimed he didn’t have enough money to buy a bomb. Two days later, Sharif reamed him for disappearing.

“By tomorrow, you need to go to the store and you need to get a prepaid cell phone. They cost little money. And we need to have communication with you at all times,” he told Suarez in a phone call. “If you can do that, I will talk to the brothers and I will say you are serious and I will tell them you made an honest mistake.”

By July 16, Suarez was back onboard. He told Skaik he wanted to sneak onto the beach in the middle of the night to bury a bomb in the sand and then detonate it with his phone in the morning.

“The next day I just call and the thing is gonna, is gonna make… a real hard noise from nowhere, and like people are gonna be like, ‘What? Where this shit came from?'” Suarez said.

So on July 27, 2015, using a connection from Sharif, Suarez bought explosives from a guy in a white Toyota Camry outside Benihana. After handing over a backpack bomb and giving Suarez instructions on how to detonate it, the driver bid farewell.

“In-sha’ Allah” – God willing – “I’ll see your act on CNN here real soon,” he said.

“By the end of the week,” Suarez promised.

Described by friends and family as naive and gullible, Suarez fell deep into internet chat rooms and bloody ISIS videos.

U.S. Attorney’s Office

Suarez’s long-imagined cable news debut took even less time than he’d guessed. As soon as he stepped out of the Camry with the bomb, dozens of FBI agents swarmed the Benihana parking lot and hauled him off to jail. The following evening, CNN host Jake Tapper raised his eyebrows as he told viewers of “another American ISIS sympathizer arrested and charged with plotting a terrorist attack here in the United States.”

In jail, Suarez would learn that his friend Skaik was a paid informant for the FBI, that the man in the Camry had been an undercover federal agent, and that the bomb he’d left with wasn’t even active.

He sat behind bars for more than a year and half waiting for trial. In a May 2016 letter to the courts, he complained about being kept in solitary for nine months, saying he hadn’t received any paperwork and been allowed only one legal call and a few visits to the law library.

As he awaited his day in court, his intelligence became a central part of the case. While prosecutors were adamant that a mass tragedy had been narrowly avoided, friends and relatives rose to Suarez’s defense, describing him as a naive kid who was, as one co-worker said, “Forrest Gump slow.” His lawyer asked the judge for a mental health evaluation and told reporters his client was “very immature for his age” and had “a very low intellect.”

His attorney’s concerns are not uncommon in terrorism prosecutions. Since 9/11, the Department of Justice has charged more than 800 people for terrorism-related crimes, almost all of whom were convicted. A third of those instances have involved the use of a confidential informant to build cases against defendants that critics say are oftentimes mentally deficient or straight-up ill.

Some of the most egregious abuses of power have happened right here in Florida. In a 2006 sting, the FBI arrested the so-called Liberty City Seven, members of a cultish Miami group called the Universal Divine Saviors. Using informants, the feds approached the impoverished Haitian-Americans with promises of $50,000 in exchange for their verbal support of Al-Qaeda. The case was an embarrassment to prosecutors that ended in two mistrials and two acquittals.

His attorneys argued Suarez was simply too timid to stand up to the FBI sources.

Another controversial case was made against a mentally ill Kosovar immigrant in Tampa who unwittingly met with an undercover agent to film a video pledging retaliation for the death of Muslims. Rather than arresting him for providing material support to terrorists, the FBI continued to press Sami Osmakac – whom they privately referred to as a “retarded fool” – until he finally bought an arsenal of guns and explosives from an undercover source. That way, they could tack on a charge for attempting to use weapons of mass destruction.

It’s a tactic the feds often use to score points with juries, says German, the former FBI agent who is now a counterterrorism scholar with the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law.

“That’s actually a hallmark of these cases,” he says. “Again, it’s more about theatrics and convincing a judge and jury… If the issue is that this person poses some kind of threat, getting them off the street as fast as possible would be the solution.”

Suarez’s lawyer would make the same argument at trial in February 2017 after Suarez rejected a plea for 20 years in prison. Inside the federal courthouse in Key West, defense attorney Richard Della Fera suggested that Suarez “is not even a practicing Muslim and knows very little, if anything, about the Islamic religion.”

“The federal government mounted a full-fledged investigation using all their resources and all of their power against a 23-year-old kid living in Stock Island, living in his parents’ apartment… just to reel in this little fish, this little fish flopping around the shores of Key West,” he argued.

But prosecutors told the jury that Suarez had both the intent and the means needed to carry out an attack in the Keys. He was so dangerous, they asserted, that the FBI believed it necessary to track him at all times, assigning 30 to 40 agents to secretly follow him around on a daily basis for nearly three months.

“He was ready to blow up people on the beach,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Karen Gilbert said. “He couldn’t wait to do this.”

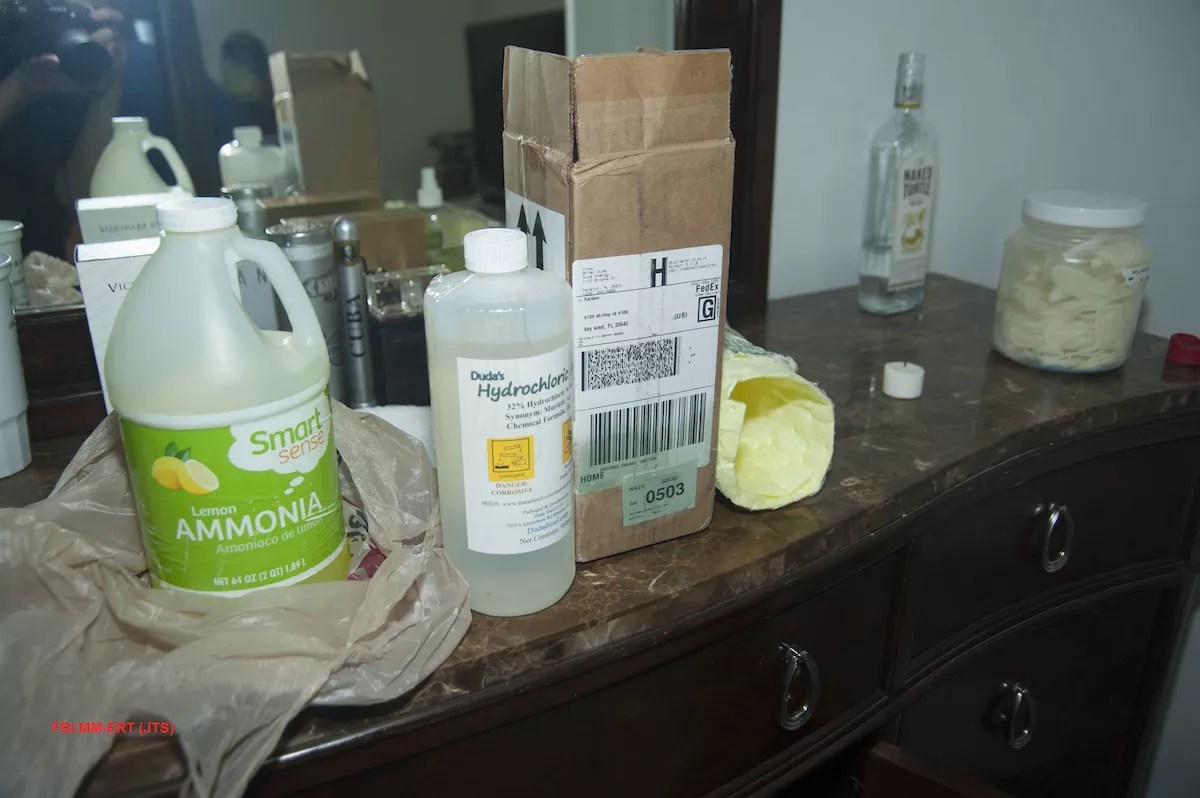

At the eight-day trial, jurors watched the recruitment video Suarez made at the motel and saw photos of bomb-making materials inside his bedroom. Transcripts of his conversations showed him callously talking about murdering cops, chopping off Barack Obama’s head, and killing anyone who got in his way.

But other portions of the evidence made Suarez seem like a hopeless rube. At least twice, he asked about acquiring an invisibility cloak, which he sincerely believed the U.S. military had. Another time, while planning the Fourth of July attack, he couldn’t remember what year it was. “So we are in 2015, right?” he asked Skaik. In Facebook messages, he even professed a belief in the Illuminati.

His attorneys argued that Suarez was simply too timid to stand up to the FBI sources and that he lacked the kind of follow-through necessary for a terror plot. They pointed out that after he watched videos on how to make a bomb, he tried – and utterly failed – to make one in the carport underneath his family’s apartment. Della Fera noted that Suarez frequently dodged calls from the informants and even faked a hospitalization to avoid hanging out with them.

He asked about acquiring an invisibility cloak, which he believed the U.S. military had.

On the witness stand, Suarez told jurors he worried Skaik might hurt his parents once he figured out where they lived.

“I felt threatened and I felt forced,” he testified. “I did not want him to figure out that I was not the person that they thought I was… And that is why I behaved the way I did and said things that supposedly the Islamic group says.”

At the end of the trial, Della Fera concluded that although Suarez had no diagnosable mental health disorders, the 25-year-old was a “somewhat slow, somewhat naive kid” who was “the victim of entrapment, plain and simple.”

It took jurors just 47 minutes to decide for themselves which Suarez – the menacing ISIS wannabe or the dimwitted kid who couldn’t say no – accepted the fake bomb from a federal agent. On January 31, they found Suarez guilty of providing material support to a terrorist organization and attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction.

When it came time for Suarez’s sentencing in April, the evidence was too overwhelming for U.S. District Judge Jose E. Martinez. Despite noting that Suarez was “not well-acted,” that “his communication skills stink,” and that “he doesn’t do things right,” the judge agreed with prosecutors that a life sentence was appropriate.

“That doesn’t really change the fact that he was really trying to do it and that he was really opening himself up to exactly what happened to him, which is that he got busted,” Martinez said.

Suarez’s parents were shocked when investigators discovered bomb-making supplies in their son’s bedroom.

U.S. Attorney’s Office

On a midsummer weekday, Milas Leconte sits at an outdoor table eating Korean barbecue tacos a few hours after punching out at his city job. The Caroline Street restaurant is just a few miles from the Benihana where Suarez got busted, and with the chatter of day drinkers in the distance, it’s hard to imagine the havoc he could have wreaked on the small tourist town.

“As of today, it feels like I never really knew him,” Leconte says. “So it’s not a betrayal. You can’t be betrayed by someone you don’t know.”

As the debate rages on in Key West about whether Suarez was sinister or just slow, his case remains part of a spirited debate about how the FBI uses confidential informants in terror cases. Since Suarez’s arrest, four other Florida men, two of whom were homeless, have been the targets of federal stings. While it’s true the FBI has conducted undercover operations for decades and successfully stopped a countless number of real plots, critics say the agency’s best practices have been more or less abandoned over the past 16 years.

“If before 9/11 I had called the FBI headquarters proposing an undercover operation targeting someone who had no involvement with real terrorism organizations, no weapons, no means to obtain weapons, and no developed plot, I think they would have thought I was crazy and probably sent me to counseling,” says German, the former undercover agent. “But the FBI has adopted, and aggressively so, this methodology where they target people with that description.”

After leaving the FBI in 2004 over differences of opinion, German wrote a book titled Thinking Like a Terrorist: Insights of a Former FBI Undercover Agent, exposing what he views as major flaws in the agency’s counterterrorism strategy. Today he believes many prosecutions are for show, not for safety.

“We’re using statutes designed to address actual terrorists against people who are suffering some kind of mental illness or personality disorder, and I think it’s a mistake over the long run,” he says.

But with recent shootings in Orlando, San Bernardino, and Garland, Texas, federal officers trying to prevent those attacks can feel stuck between a rock and a hard place. Seamus Hughes, the deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, says that in many ways, “the leash has been shortened.”

“He was a normal boy until he got caught up. They put it in his head that he could do this.”

“We don’t have non-law enforcement means to intervene with an individual we’re worried about,” he says. “We’re seeing law enforcement less willing to go out on a limb to try more creative approaches to these things.”

And Hughes says it can be hard to tell if someone’s verbal threats of violence are serious or whether a person sympathizing with a terrorist organization poses a real danger.

“Absolutely there are cases where mental health issues are a concern, but there are also cases where people are going into this clear-eyed,” he says. “You can be a knucklehead who can also hurt a lot of people. You don’t have to be a genius to shoot up a nightclub, and I think that’s the struggle that law enforcement is trying to deal with.”

With Suarez locked up for life, his attorneys are appealing his sentence, pointing out that other young recruits received far less time for similar crimes. According to Hughes, just one other defendant, Justin Sullivan of North Carolina, has received a life sentence in an ISIS-related case.

Back at home in Key West, friends say Suarez’s father shows the stress on his face, while his mother has lost so much weight she has nearly withered away. Their consensus is that their son got in over his head and didn’t know how to back out.

“He was a normal boy until he got caught up,” family friend Pamela Sanchez says. “He started getting influenced by other people. They put it in his head that he could do this too.”

Leconte, a father of two himself, says he can only imagine Suarez’s parents’ pain.

“It’s the worst fear, knowing you can do everything right, raise him right, and it still turns out like this,” he says. “It’s very devastating.”

What’s most frustrating to him is there’s no clear answer for why Suarez did it. He came from a good family, had a small circle of friends, and seemed – at least on the surface – content with his life.

“I think to join up with ISIS and be a terrorist, you have to have a lot of despair, but I didn’t see that,” Leconte says. “It’s not like he was picked on like some Columbine stuff. Nothing like that.”

So what fueled his embrace of extremism?

“I can’t really fathom what went through his mind,” Leconte says. “Only Harlem knows.”