Illustration by Pete Ryan

Audio By Carbonatix

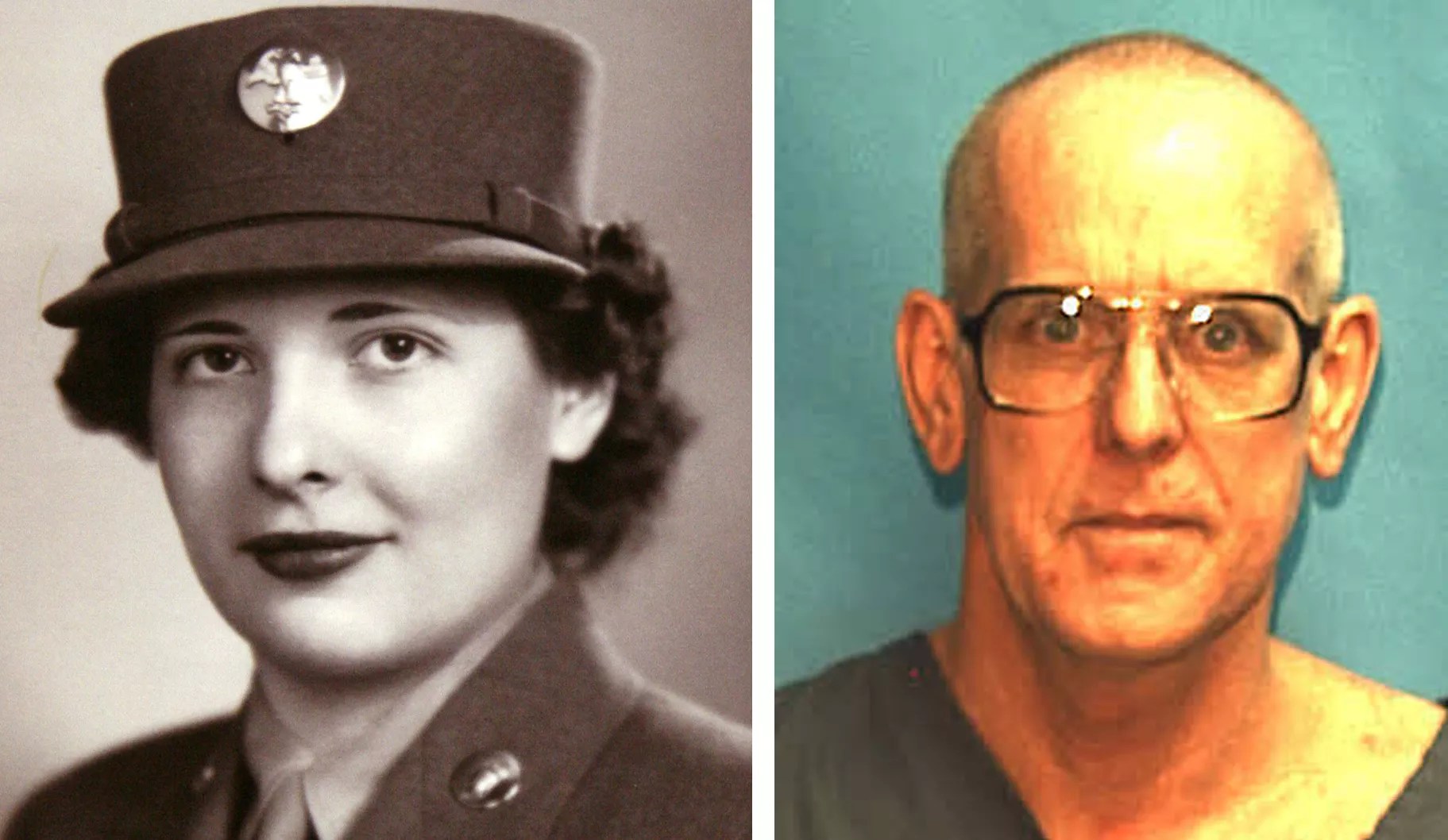

At her home in the tiny village of Palm Springs, just outside Lake Worth, Anna Mae Kiger started each morning the same way. After rising around 7, she walked down the driveway to pick up her newspaper. Then the 75-year-old Air Force veteran hoisted an American flag high up a pole in her front yard and saluted it.

But early on August 2, 1996, Varinee Testa, one of Kiger’s neighbors, noticed the elderly woman’s paper still lying outside. As the hours ticked by, Testa grew worried. Around 11 a.m., she called Kiger’s sister, Gladys Rowan, to check things out.

Fearing the worst, the two approached Kiger’s L-shaped stucco home together. They tried opening the front door with a spare key, but Kiger had locked it from the inside with a chain. As Testa and Rowan surveyed the back of the house, they noticed a sliding glass door was ajar.

The two entered and called out for Kiger. They checked her living room, then the guest bathroom. In the master bedroom, they found the septuagenarian face-down on a blood-soaked pillow on the terrazzo floor. Behind her back, her hands had been tied together with the cord of a lamp still standing perfectly upright beside her body.

Within seconds, the home phone rang. Rowan answered, stunned, as a deputy with the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office told her he was investigating a hit-and-run involving Kiger’s Oldsmobile. As it became clear the case had turned into a homicide, detectives sped toward the house to secure the scene.

At first, investigators were hard-pressed to find a motive. But soon deputies discovered the old woman’s missing 19-inch Zenith TV set in a crack house about a mile away. A tipster who read about the TV in the Palm Beach Post then called the Sheriff’s Office to report a drug-addicted neighbor named Larry Johnson who often sold stolen goods for crack.

It was detectives’ first real lead. They returned to the crack house, where a witness told them Johnson had traded the TV for a hit of cocaine the previous night. With the new information, investigators dusted Kiger’s home and found two of Johnson’s fingerprints on the door jamb of a hallway closet.

Three months later, detectives tracked down Johnson in South Carolina and arrested him. In an interview, the house painter admitted to borrowing $10 from Kiger, a former customer, one night around the time she was strangled to death. The 35-year-old claimed he left to buy crack after she gave him the money, but he didn’t explicitly deny involvement in her murder.

“I don’t know what else happened the rest of that evening,” he told detectives. “I don’t believe I could actually do that, but under the influence of crack cocaine, I’m not saying I was not capable. I just don’t know that I done that.”

But 14 years after the crime – after one set of prosecutors had given up and memories had grown fuzzy – 12 jurors agreed he was guilty. On November 3, 2010, Johnson was convicted of burglary and first-degree murder. He was later sentenced to life in prison, where he has remained since.

Now 57 years old, Johnson argues that the case was bungled and that he is innocent. And he’s not the only one who believes his trial was flawed – for the past year, law students with the University of Miami’s Innocence Clinic have parsed Johnson’s case and found multiple inconsistencies. Clinic director Craig Trocino says the evidence raises questions about Johnson’s guilt.

“It’s a horrible crime,” Trocino says, “but we have serious doubts that they got the right guy.”

For starters, two witnesses who testified against Johnson were chronically addicted to crack; one couldn’t even identify him in a photo lineup. DNA found under Kiger’s fingernails failed to definitively identify Johnson. Some of the evidence, including an unknown DNA profile on the bloody pillow and an untested set of fingerprints on the roof of Kiger’s stolen car, even suggested someone else could have been responsible for the killing.

In the seven years since his trial, Johnson has made numerous attempts to appeal the conviction, calling the evidence shaky and the eyewitnesses less than credible. Though he doesn’t deny his long history of substance abuse and drug-related crimes, he insists he’s no murderer.

“I’m not asking to just be let go; I’m asking to get a fair trial,” he pleads. “That’s what America is about.”

Anna Mae Kiger, in an undated photo from her service in the Air Force, was strangled to death in August 1996. Lawrence Johnson Jr. was convicted of her murder 14 years later.

Anna Mae Kiger photo courtesy of the Palm Beach Post / Mug shot courtesy of the Florida Department of Corrections

On a sunny December morning, Lawrence Johnson Sr. sits at the kitchen table inside his family’s home in Palm Springs. It’s a country-style house, with a half-dozen pine trees and a decorative wishing well in the front yard. He and his late wife Toni lived in a two-bedroom next door for almost a decade, but when she became pregnant with their third child in 1970, the couple bought the adjacent property and built a three-bedroom home with the help of Johnson’s hunting buddies for about $25,000.

“All the stones on the front of the house that you see, my wife scrubbed every one of them with a scrub brush and a bucket,” he says proudly.

Larry Sr., a chatty 77-year-old with wire-rim glasses and a trim white mustache, grew up in Michigan but moved to Florida when he was 5. He and his wife met at Lake Worth High School and married in 1959, when he was 19 years old and she was 17. Larry Jr. was born on their first wedding anniversary, followed by Gary in 1967 and Bonnie in 1971.

In the tight-knit community of Palm Springs, Larry Sr. started a painting business, while Toni worked as a teacher’s aide in the library of a nearby elementary school. They were young and fun, but somewhat straitlaced.

“We led a pretty sheltered life,” Larry Sr. says. “We never did pot… Bonfires on the beach, we’d come in with our Pepsis. Everybody used to razz us and laugh at us, going to a beer party with Pepsi, but we didn’t like beer. And to this day, I may drink one a year with my daughter at dinner.”

Growing up, the three kids were close to one another and their parents. Larry Sr. returned each evening from his house-painting business, and the family of five sat down for dinner every night around 6. They spent weekends hunting in the Everglades and diving in the Keys.

“We were always a family that did everything together,” Larry Sr. says.

In school, Larry Jr. made friends easily and had several long-term girlfriends. As a teen, he worked at Pizza Hut and earned extra money putting shutters up for his dad’s customers during hurricane season. Gifted at all things mechanical, he was the go-to guy when his classmates had car problems.

After graduating from Leonard High School in 1978, Larry Jr. went to work with his dad and fixed cars on the side. Good with his hands and with customers, he had no trouble making money.

“Part of the gratification of painting people’s homes and all, it looks nice when it’s done,” Larry Jr. says. “They get satisfaction; I get satisfaction. I was a working man. I may have messed up, I may have been partying all weekend, but I worked. I love working.”

It was while partying in his early 20s that Larry Jr. entered the drug scene. He started smoking a little weed; then his cousin got him into selling cocaine.

“We barely, rarely used any at all,” he says. “We might sit around and play Monopoly or Life all night long, and people would come over and buy and leave.”

At first, it was just a business. But over time, he began using more regularly and eventually started smoking crack.

“I’d go for two years or something without doing it, and all of a sudden I’d be off the wagon,” he says. “I’d go for three or four weeks just straight getting high.”

“Not that we ever thought that he did it, because like I said, he didn’t have a mean bone in his body.”

At the time, Larry Jr. was married to a woman named Becky, and in 1991, the couple welcomed a baby girl. But his frequent disappearances were a constant source of argument, and as he sank deeper into addiction, he began pawning household goods for drug money. One time, he sold the family’s three-wheel ATVs off the back of his truck. Another time, Becky came home and found the washer and dryer missing.

“My wife says, you know, ‘I’m tired of being second best,'” he recalls. “She said, ‘You have a girlfriend.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t.’ ‘Yeah, her name is crack. She has no arms or legs, but you give her all your attention.’ That hurt.”

Larry Sr. also began to notice items would go missing from the family’s home. Paint sprayers and ladders would disappear, and he’d later learn his son had sold them for drug money. One time, Larry Jr. marched into the house to take a TV set.

“His eyes were bugged out and he wanted his TV,” Larry Sr. says. “I said, ‘You can’t take it.’ Well, he grabbed up the TV and he went out the door with it, and I remember I walked out the door there, and I pushed the TV and it fell down on the ground… He picked it up, put it in his car, and drove off.”

Larry Jr. spent years trying to kick his habit at free treatment centers. His parents tried a tough-love approach, but it only made him feel worse. Each time he went on a binge, his self-worth plummeted, and then he’d have to get high again.

“Dad, nothing against him, ’cause I love him to death, but it’s like he would like to belittle me and try shaming me to change,” Larry Jr. recalls. “You can’t shame people into change.”

After a relapse in the summer of ’96, Larry Jr. and his wife called it quits. His parents adopted the couple’s 5-year-old daughter, but the family went months without hearing from Larry Jr. Finally, in November, they learned he had been arrested in South Carolina for Kiger’s murder.

“I was really dumbfounded,” Larry Sr. says. “Not that we ever thought that he did it, because like I said, he didn’t have a mean bone in his body.”

Today, Larry Jr. says he didn’t know Kiger was dead until detectives showed up asking questions about her murder. He says he ended up in South Carolina in August 1996 after giving a ride to a crack-smoking buddy. Larry Jr. had a van but no gas, so the two concocted a plan to steal a car from a dealership.

“I told the guy I wanted to test-drive a car, and we took off,” he says. “And that wasn’t right neither, but that’s what we did.”

From South Carolina, investigators brought Larry Jr. back to Palm Beach County, where he was ultimately indicted on a first-degree murder charge. But on the eve of trial in October 1997, prosecutors dropped the case, saying they couldn’t find two key witnesses from the crack house. Larry Sr. breathed a sigh of relief but warned his son not to blow his second chance at life.

“I said, ‘I would be so squeaky clean that I wouldn’t even spit on the sidewalk in Palm Springs,'” he remembers.

But with his addiction still roaring, Larry Jr. kept getting into trouble. In 2001, he was charged with burglary after stealing some fishing poles off a neighbor’s porch and selling them to a pawnshop. In 2005, he was picked up for pawning two weed trimmers he’d snatched from the back of a landscaping trailer. And in 2007, he was sentenced to three years in prison for swiping a motorcycle off a guy’s lawn in Martin County.

None were violent crimes, though. In a rap sheet chronicling 22 arrests, only one – the 1996 murder charge – involved another person being brutally harmed.

He was just a few weeks shy of being released for the motorcycle theft when Palm Beach County cold-case detectives showed up at the prison in 2009. By then, they’d uncovered a juicy new piece of evidence: After combining fingernail scrapings from the victim in a lab, a forensic scientist was able to locate a male DNA profile. With a search warrant in hand, investigators put Johnson in waist chains and took a sample of his saliva. A comparison to the scrapings seemed to confirm he was a match.

Detectives finally believed they had their man. Johnson was booked into the Palm Beach County jail once again and charged with Kiger’s death.

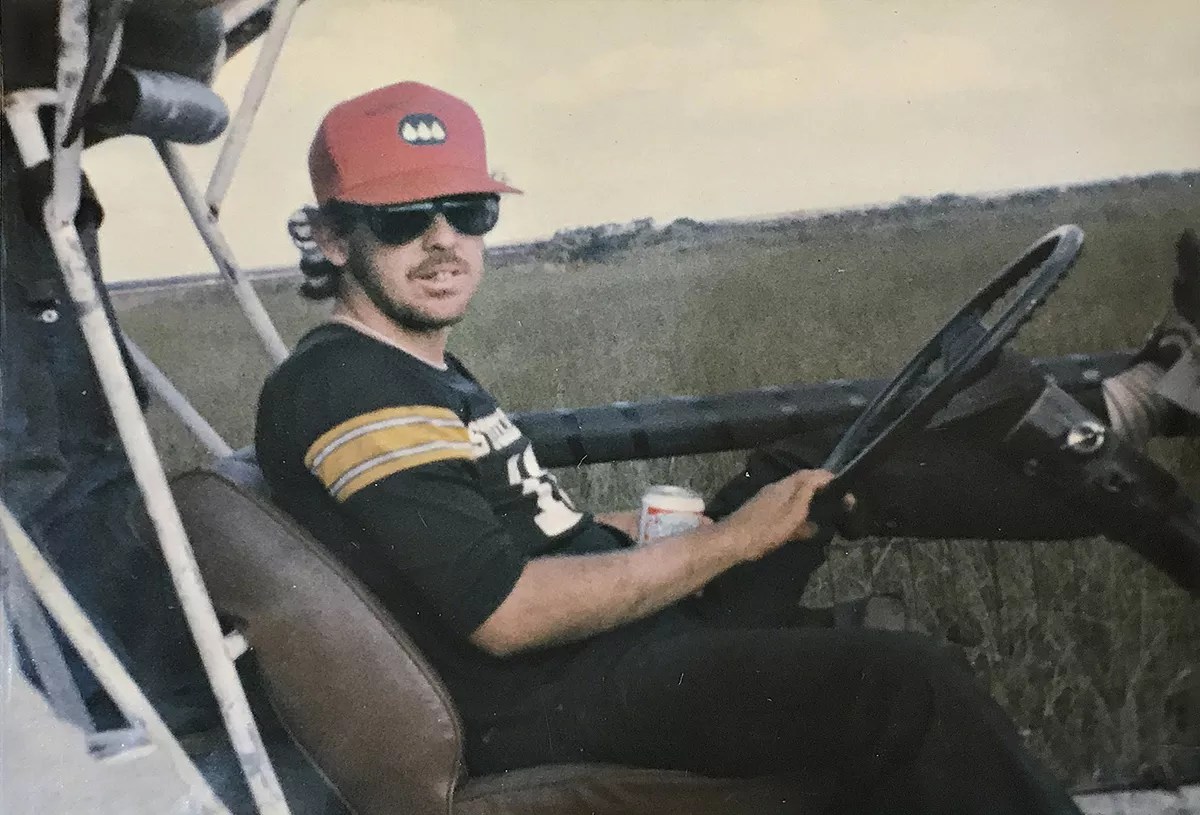

Before his arrest, Larry Jr. enjoyed hunting, diving, and riding swamp buggies.

Courtesy of Lawrence Johnson Sr.

A single memory from a self-proclaimed crack addict – a moment spanning less than five minutes – helped investigators craft their narrative of the murder.

Hours after Kiger’s body was found, deputies recovered her stolen TV at a Lake Worth crack house and interviewed a number of drug addicts who hung around there. One of them, Kelly Smith – a scrawny, 28-year-old coke dealer who’d been a paid confidential informant for the Sheriff’s Office – had a remarkable story about the TV set.

In the early morning of August 2, 1996, Smith was sleeping at the crack house when Johnson came in with the TV, she said. From her perch on the couch, she saw him sell the Zenith to a guy who lived there. As she drifted back to sleep, she had a clear memory of the men hooking up the TV inside the home.

By the time of Johnson’s second arrest 14 years later, Smith had gotten sober, making her a more suitable witness for the state. Her recollection put Johnson in possession of the stolen TV set on the eve of the murder – the clearest sign yet he was responsible for killing the elderly woman.

With Smith’s statement secured, prosecutors were confident there was enough evidence to convict Johnson. A Palm Beach Sheriff’s deputy had seen a person in a white cap driving Kiger’s stolen car to and from the crack house the night of the murder, adding credibility to Smith’s story. The forensics – the two fingerprints on the hallway closet and the DNA from Kiger’s fingernails – also pointed at Johnson.

“You will get to see all the evidence in this case,” prosecutor Chris Keller told jurors the first day of trial in November 2010. “You will see that that man killed Anna Mae Kiger for crack cocaine.”

Smith was one of two witnesses who frequented a pair of crack houses where Johnson was a regular. The night Kiger was killed, Johnson made three visits to one of the homes – once with some food stamps to sell, once with the TV, and a third time with a bag of jewelry, Smith told jurors. His visits were late, probably between midnight and 4 a.m., she testified. On the final visit, she said, she bought a pearl ring from him.

“Without a shadow of a doubt, it was Larry Johnson,” Smith said.

Another addict, Michelle Martinez, testified Johnson was driving her to another Lake Worth crack house when they spotted police out front. Johnson, who was wearing a white painter’s cap, seemed nervous.

“He looked at the police and said, ‘Oh, shit, there they are,'” Martinez remembered. “I asked him, ‘Well, what are they looking for, you?’… I don’t really remember what it was, but he had mumbled something regarding a television.”

The state’s case didn’t hinge only on the testimony of the two drug users. The county medical examiner told jurors Kiger had been beaten so badly before she was strangled that parts of her teeth were found on the bloody pillow. The director of a private forensics lab testified that male DNA had been found underneath her fingernails, indicating Kiger might have clawed at her attacker to loosen his grip around her neck. The sample “cannot exclude Lawrence Johnson,” he told the courtroom.

Jurors also heard that two of Johnson’s fingerprints had been found on an air-conditioning closet in the hallway. Although Johnson and his father had painted the interior and exterior of Kiger’s home, prosecutors could find no record of Larry Jr. being inside the house after April 1987.

Finally, the state played Johnson’s taped interview with detectives from 1996, including his comment that “under the influence of crack cocaine, I’m not saying I was not capable.” In closing arguments, prosecutors said there was no way around it: Johnson had killed Kiger for drug money.

“When you add all of that up, add the fingerprints in the house, the DNA, his statement, the TV, the jewelry, if you start adding all the pieces together, it only points to one logical conclusion,” Keller said. “That man, the defendant, committed that crime.”

Throughout the trial, Johnson’s lawyer, Gregg Lerman, aggressively questioned the state’s witnesses but ultimately presented none of his own. When the state rested its case, Lerman also rested.

Johnson started to get nervous.

After a three-day trial, jurors took a little longer than four hours to deliberate. When they returned to the courtroom, the clerk read the verdict: guilty of first-degree murder, guilty of burglary. Johnson was crestfallen, but not entirely surprised.

“I feel my lawyer let me down by not presenting no kind of defense,” he says. “I don’t blame a jury in a sense, when they only heard one side of a story.”

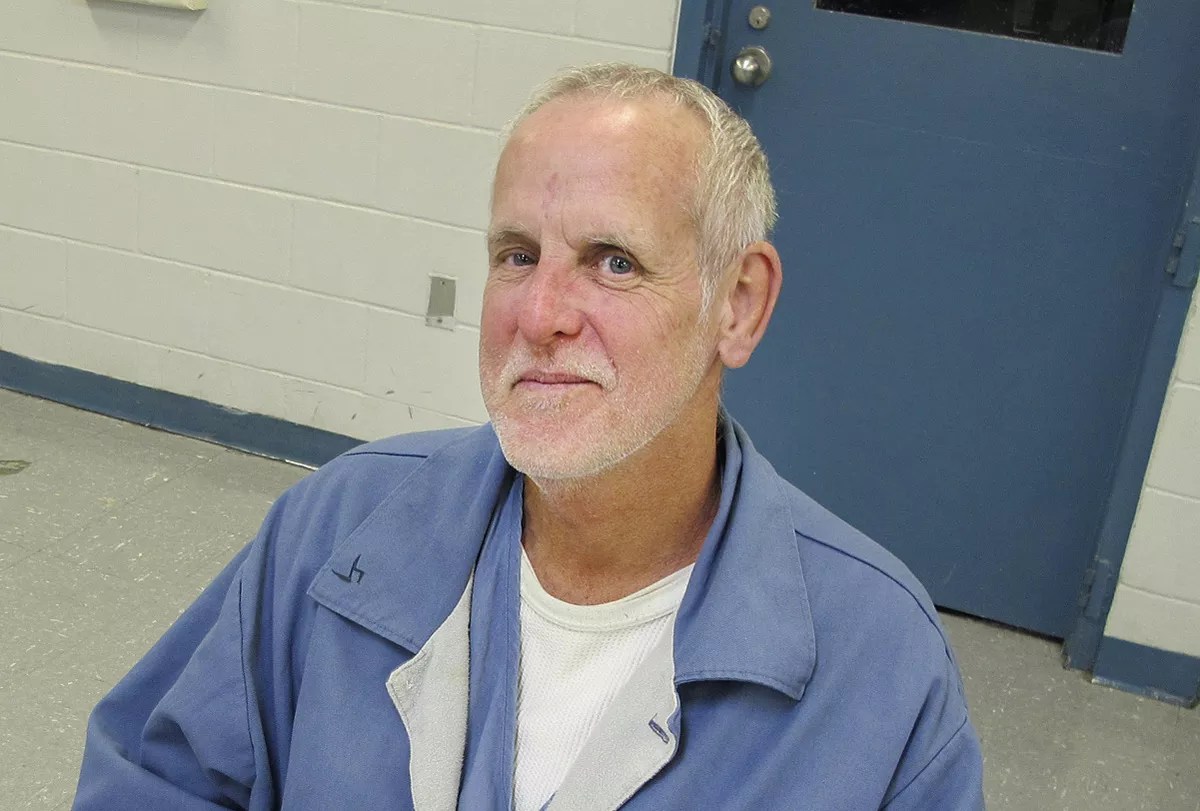

Johnson, who works as a law clerk at a North Florida prison, says prosecutors and his defense attorney bungled his case.

Photo by Jessica Lipscomb

Three hundred fifty miles from home, Johnson sits in an empty visitation room at the Hamilton Annex in Jasper, a town of about 5,000 people near the Florida-Georgia line. Dressed in a cornflower-blue uniform that matches his eyes, his posture is relaxed and his words come out like a whistle. Seven years into a life term, he is eager to get out of prison but patient about the process.

“Everybody says, ‘Oh, you’ve got a life sentence – why are you so calm?'” he says. “What’s it gonna do to get mad? I need to channel my focus.”

Frustrated by the legal system, Johnson entered the prison’s law clerk training program in August 2013 and earned his state certification the following December. For the past three years, he’s worked with inmates in administrative or disciplinary confinement, fetching copies of their legal paperwork and helping type up court motions.

“It’s a challenge to help these guys, but there are some rewards,” he says. “A guy just came up to me at lunch. It was so good. He got an evidentiary hearing – he’s going back to court. And he’s thankful.”

With his new training and on-the-job experience, Johnson also began putting muscle into his own case. He read stories about inmates being freed after decades in prison and fired off letter after letter to legal groups specializing in wrongful convictions. After many rejections, he finally got a bite from the Innocence Clinic at the University of Miami law school.

Taken as a whole, the case against Johnson comes down to three main points, all of which have problems: his fingerprints inside Kiger’s home, the DNA found underneath her fingernails, and the statement from Smith about the stolen TV.

But even more evidence casts doubt on Johnson’s guilt. In case files, one interviewee told police about another plausible suspect who was never investigated. Two crucial pieces of forensics excluded Johnson, while the fingernail DNA never definitively pointed to him as the killer. Finally, the state’s narrative about the TV being sold at the crack house contained multiple inconsistencies.

“Their story is basically stacking inferences to get something, and a jury bought it,” Johnson says.

Starting from the very first day of the case, there were other possible suspects detectives could have investigated. A neighbor of Kiger’s told deputies she saw two black males loading or unloading “some fairly large unknown items” beside two dark-colored vehicles outside Kiger’s home around 5 p.m. the night of the murder. Hours later, when Kiger’s stolen Oldsmobile was ditched in a hit-and-run, the driver of the other car told deputies that one or two black males fled the vehicle.

With his new training and on-the-job experience, Johnson also started putting muscle into his own case.

During the initial investigation, detectives also heard from a homeless man who said he knew someone who might have been responsible. In an interview just six days after Kiger’s body was found, Richard Nicastro told investigators that a guy named Kenny was living in one of Kiger’s homes when he “burned it down.”

“I remember him bragging to his friends that he was going to get the old lady,” Nicastro said. (New Times isn’t using Kenny’s full name since he was never officially implicated.)

If investigators had looked harder, they would have found the broad strokes of Nicastro’s theory to be true: Court records confirm a property arrangement between Kenny and Kiger, and an old Palm Beach Post article shows a fire at the house in 1974, although that was six years before Kenny moved in. Still, there’s no indication detectives ever investigated Kenny as a suspect.

There was also physical evidence that suggested someone other than Johnson could have been the killer. According to a crime lab analyst, DNA from at least two people was found on the bloody pillow where Kiger’s face was resting, but Johnson was not a match. His fingers also didn’t match a set of prints found on the roof of Kiger’s stolen Oldsmobile; there’s no indication detectives ever ran those key pieces of evidence through a database to find a match.

“These are key things that would have made a difference,” Johnson says.

It’s also notable where DNA and fingerprint evidence wasn’t discovered. Lab scientists found nothing on the lamp, the lamp cord, or a pair of broken eyeglasses in Kiger’s hallway. No prints were on the stolen TV, and it was never swabbed for DNA. The pearl ring Smith said Johnson sold her at the crack house was swabbed but never sent in for testing. Although the ring was mentioned at trial, it was never authenticated by the state as belonging to Kiger. Likewise, no explanation was given for the letters “DB” – possibly initials – that were engraved on the inside.

The forensics that put Johnson at the crime scene can also be explained away. Johnson says he remembers painting the door frame of Kiger’s air-conditioning closet where his prints were found. A fingerprint technician admitted on cross-examination that it was possible for prints to remain undisturbed for years, especially in an indoor environment.

Then there’s the DNA found in two samples of Kiger’s fingernail scrapings. According to the results, the DNA profile for one sample could match one of every 894 men; for the other sample, one in every 171 could be a match. Extrapolated to the U.S. population at the time, that means more than 167,000 American men could have left the DNA found in the first fingernail sample, while more than 877,000 could have contributed to the second sample.

In early January, New Times showed a copy of the DNA report to Anthony Tosi, a former forensic scientist with the New York City medical examiner’s office. Now an anthropology professor and molecular forensics researcher at Kent State University, Tosi says the DNA from the fingernail scrapings is relevant, though it does not point exclusively to Johnson.

“It’s not the slam dunk you need when you’re looking at forensics,” Tosi says. “You really need other elements of the case to nail this down.”

In the state’s case, that’s where Smith and Martinez came in. The night of Kiger’s murder, Smith said Johnson visited the crack house three times between midnight and 4 a.m. in a blue or green car. But if that’s true, Johnson couldn’t have been the person deputies saw in Kiger’s stolen vehicle. Reports from the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office say the person in the white cap got out of the Oldsmobile around 9:30 p.m. and peeled away from the crack house 30 seconds later. By 10:33 p.m., the car was reported in a hit-and-run and towed away.

Martinez’s story about Johnson mumbling something about a TV also lacked a clear identification; in a photo lineup, she was unable to pick out Johnson’s face.

Finally, prosecutors misled the jury by conflating two crack houses. A Palm Beach County Sheriff’s deputy said he saw the Oldsmobile outside a home on the 3600 block of Davis Road, but the stolen TV was recovered from a crack house at 3360 Canal Rd., a block or so away. The prosecution seemingly blended the two together, referring to “the crack house on Canal and Davis” while questioning Smith.

“The crack house where you found the victim’s property is not the crack house you told the jury I was at,” Johnson says incredulously. “That’s two different places.”

In a nearly two-hour interview with Johnson, it’s clear these discrepancies haunt him. With help from the UM Innocence Clinic, he hopes a judge will see what he sees.

“It’s a big mess,” he says, exasperated. “I feel like my whole case was just they wanted somebody, and because of the fingerprints, it’s plausible. Because I was using at the time, I have no alibi. I’m stuck.”

On the second floor of the law school at the University of Miami, Craig Trocino sits in an office surrounded by dozens of boxes of legal paperwork. Each one is stacked neatly atop another and labeled with a particular inmate’s name: Sosa, Clapp, Bedsole. Every week, the school’s Innocence Clinic, which Trocino runs, is inundated with as many as 20 letters from prisoners who proclaim their innocence.

“There is this underserved population who nobody wants to hear from, people who are indigent and have been convicted of a crime,” Trocino says. “So everybody just takes the key, locks the door, closes the book, and moves on.”

Each year, eight students are selected to work with the Innocence Clinic, which was founded at UM in 2011. Heading into spring 2018, Trocino says the clinic is actively fighting seven convictions and investigating another 40, including Johnson’s.

The clinic only takes on cases of actual innocence, meaning Trocino and the students don’t get involved in crimes involving self-defense or insanity. Death penalty cases, which are too burdensome to investigate, are also disqualified, along with federal cases and out-of-state convictions.

“The two eyewitnesses that testified against him were both severe drug-users,” Trocino says.

Less than half of all incoming letters meet those requirements, and after further vetting, an even smaller number are chosen for follow-up investigation. Because faulty eyewitness testimony and false confessions are two of the leading causes of wrongful convictions, inmate letters that mention those scenarios often get a second look.

“That’s what initially drew me to Larry’s case, because the two eyewitnesses that testified against him were both severe drug users,” Trocino says.

The team also found the DNA evidence troubling. Trocino says a private analyst is reviewing the crime lab reports in Johnson’s case, including the one showing he matched the DNA underneath Kiger’s fingernails.

“If you look at the frequency population statistics on it, they are extremely low – troublingly so, at least in my opinion,” Trocino says. “If it were a normal DNA hit, where normally it’s 6 million or 600 million to one, then we’re not having this conversation. But it’s [roughly] 800 to one, with a lousy ID.”

Depending upon what they learn, Trocino and his students could ask a judge to retest the DNA or other items, such as the ring or the fingerprints from the stolen car.

“Those are some of the things we’re still looking into,” Trocino says.

While the clinic slowly works to reinvestigate the case, Johnson wakes up each morning in prison and waits for more news, some days more patiently than others.

“We can’t make the courts do something, but as long as you can get back to the court, you can argue your side,” he says. “And I haven’t been given that chance.”

Since Johnson has been locked up, at least five of his close relatives have died, including his mom and younger brother. While he was awaiting trial, his 18-year-old niece overdosed on morphine, a death that shook him to his core.

“I see her as a young girl that didn’t get a chance at life,” he says. “I might have messed it up, but I still had life. And this girl’s not going to get those chances.”

These days, he’s focused on two goals: staying clean and getting out of prison.

“The Bible says the truth will set you free,” he says. “Everybody needs to have their own belief and their own understanding, but mine is that it will all come out one day and I’ll be home – and hopefully before my dad passes away.”

At age 77, his father bears the burden of the same thought. But there’s more sadness in his voice as he sits in the home he built for a family that’s no longer with him.

“It’s been a road. Like I said, I lost my wife in ’11. Lost Gary two years ago… Now with Larry being in there, the only one I got left is of course Ashley and Bonnie,” he says wistfully. “I know I’m not going to be around much longer. I’d really like to see something happen.”