Screenshot via change.org

Audio By Carbonatix

Coconut Grove is Miami’s oldest neighborhood, and it’s one with deep Black roots: Bahamian settlers who lived in what is now known as the West Grove literally built much of the city we know today. It’s a neighborhood with a strong spirit, one that residents are fighting to defend 126 years after the Grove was incorporated as a new redistricting proposal threatens to split the community in three.

The redistricting comes on the heels of the 2020 U.S. Census results, which revealed what many have known for a while: The City of Miami is growing – fast. From 2010 to 2020, Miami’s population swelled from just under 400,000 to more than 442,000, with much of that increase attributed to out-of-state transplants moving into Brickell and downtown, both of which are located in Miami’s City Commission District 2. In times of uneven growth, the city hires a consultant to redraw the map of the five commission districts so that each sector represents an equitable population. The city previously hired attorney and lobbyist Miguel A. De Grandy for the job in 2013 and brought him back again to siphon roughly 28,000 voters out of District 2, which encompasses most of Miami’s coastline, into other districts.

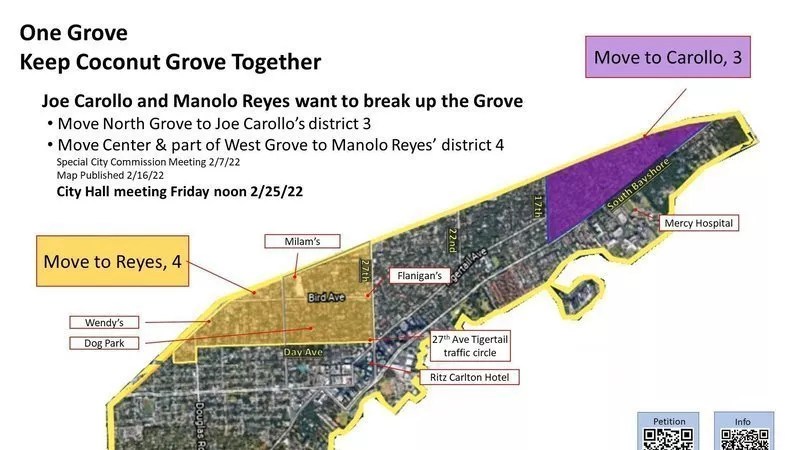

The process is meant to keep communities intact and protect minority voting blocs. But Coconut Grove residents are arguing that the proposed redistricting map, which was first presented to the Miami Commission on February 7, does the opposite.

It moves parts of the Grove, which previously resided entirely in District 2, into Districts 3 and 4, which are currently represented by Commissioners Joe Carollo and Manolo Reyes, respectively. Most egregiously, residents say, a large swath of the historically Black West Grove will be absorbed into Reyes’ District 4, which is dominated by Hispanic voters.

“People from West Grove are heavily involved in Miami politics,” Rev. Nathaniel Robinson III of Greater St. Paul A.M.E. Church in the West Grove tells New Times. “If you move the Black voters out of District 2, even half of them, and put them into a majority Latino district like District 4, you have diluted that vote.”

Residents – Black and white – have banded together to fight the redistricting proposal. They’re active on the Grove Watchdog Group on Facebook, where they post links for residents to give testimony to the commission, brainstorm slogan ideas, such as “One Grove” and “One District,” and circulate a petition called “Keep Coconut Grove Together,” which had garnered more than 1,500 signatures as of Thursday evening.

On February 22, the city released a new proposed redistricting map (attached at the end of this article). It scales back some of the District 4 encroachment but still carves out a significant portion of the Grove’s Black community from District 2.

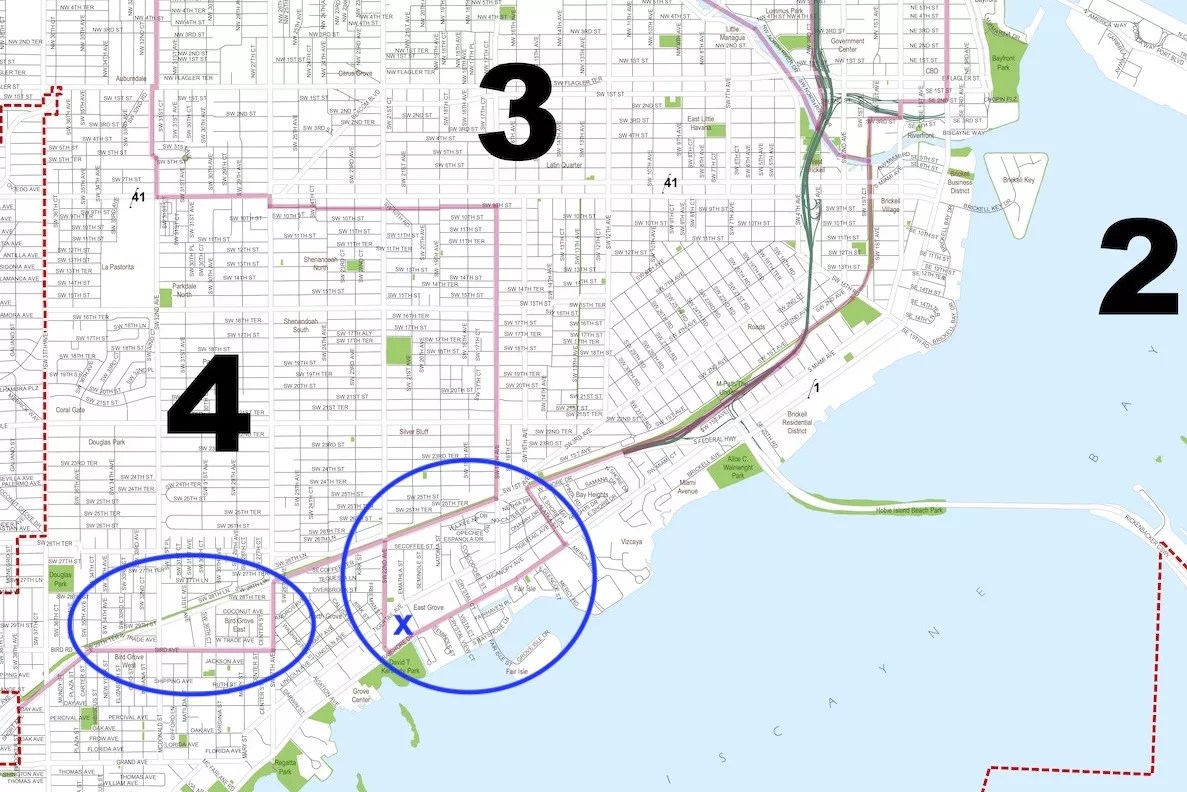

This detail of a revised map submitted by attorney and lobbyist Miguel De Grandy shows proposed adjustments to the Coconut Grove carveouts. The one on the left would transfer a swath of the West Grove into Manolo Reyes’ District 4, while the one on the right, which would go to Joe Carollo’s District 3, includes a Carollo- owned house (marked with an X) that has been the subject of controversy.

Base map and district lines via City of Miami

Residents still aren’t satisfied.

“Whether we’re Black, white, Latino, or other, we are one Grove,” Robinson asserts. “At least let us stay together.”

Before the City of Miami was incorporated in 1896, Black settlers from the Bahamas arrived in Miami during the 1870s and built homes in the Bahamian village that would become Coconut Grove. Those Bahamians would settle along the historic Charles Avenue. They built some of Miami’s greatest cultural landmarks, including the Peacock Inn, South Florida’s first hotel, and the stunning waterfront estate, Vizcaya Miami.

Miami historian Marvin Dunn, who lived much of his life in the West Grove and whose work focuses largely on Black Miami history, says dividing this historic neighborhood is not only voter suppression but an attack on the Black community.

“Any attempt to break [West Grove] up is blatantly racist,” Dunn tells New Times, “and I don’t use that term often.”

Dunn explains that Bahamian Black settlers were more outspoken and politically active than the other Black people who came to Miami from Georgia and South Carolina. They always had a spirited streak and weren’t afraid to fight back against injustice.

“Whether we’re Black, white, Latino, or other, we are one Grove. At least let us stay together.”

For example, in 1921, Reverend Richard Higgs of St. James Baptist Church in the West Grove was kidnapped by eight hooded Ku Klux Klan members after delivering sermons that preached racial justice and equality. Higgs’ kidnapping sparked one of Miami’s first race riots, when Coconut Grove residents armed themselves and took to the streets looking for their preacher and demanding his safe return. (According to an essay in Tequesta, a journal published by the Historical Association of Southern Florida, the mob whipped Higgs, tied a noose around his neck, and admonished him to leave Miami within 48 hours. He fled to the Bahamas.)

“The Black community in Coconut Grove always been a very astute, active, and dynamic community,” Dunn notes.

When Commissioner Ken Russell ran for the District 2 seat in 2015, his campaign advocated for the West Grove, which has ingratiated him with the Black community there. Russell attests that Black residents in the West Grove are a vocal and civically engaged minority that comprise a significant portion of Coconut Grove’s high voter turnout. According to Russell, 65 percent of District 2’s voters come from Coconut Grove, even though the majority of its population lives in the high-density areas of downtown, Brickell, and Edgewater.

“Nothing has shown us that any additional growth has happened in the Grove compared to Brickell, downtown, Edgewater, and Wynwood,” Russell tells New Times. “If it can be accomplished in other ways, it should. Once you break up this community into three different districts, you’ve now fractured their ability to go to a common champion.”

Clarice Cooper is president of the Village West Homeowners and Tenants Association (HOATA), a group that advocates for tenant and homeowner rights in the West Grove and holds meetings to get residents involved in local government and current events. Cooper tells New Times the West Grove has long been losing longtime residents to rising property prices, encroaching gentrification, and increased development.

But there have been some promising initiatives: the creation of the West Grove Community Redevelopment Agency to promote affordable housing, the designation of two Neighborhood Conservation Districts for stricter zoning and mitigating new development, and the election of the Coconut Grove Village Council, an elected body of nine representatives that listens to the concerns of residents and business owners.

All that headway will be for naught, Cooper says, if the city goes ahead and divides the Grove into three districts.

“The entire Grove staying in District 2 is the best thing for us to accomplish the goals we have on the table,” Cooper says. “My biggest fear is that with this redistricting we’ll have to deal with more than one commissioner, which is going to impede the progress we’re trying to make.”

Indeed, if Coconut Grove is split into Districts 2, 3, and 4, the various community groups will have to interact with three different commissioners to advocate for neighborhood projects. To make matters even more complicated, Florida’s Sunshine Law prohibits elected officials from the same body from gathering at the same time outside of scheduled public meetings. That means the three commissioners who oversee Coconut Grove wouldn’t be able to attend a single community meeting together.

“You’d have to do a very complicated Sunshine dance, where one commissioner leaves the room and other commissioner stays in, and they may promise different things,” Russell posits. “It’s inconsistent representation to help with the community’s quality-of-life issues.”

On Friday, the city will hold a special meeting to discuss the newly proposed district map.

Apart from the issues surrounding the West Grove carveout for Reyes’ District 4, the carveout at the east end of the Grove promises to bring its own intrigue to the meeting. That chunk would be subsumed into District 3, represented on the commission by Joe Carollo, and it includes a house on Morris Lane owned by none other than…Joe Carollo.

Carollo has lived in a West Brickell apartment since 2016, which qualified him to run for the District 3 seat in 2017 and 2021. But opponent Alfie Leon took him to court in 2018 to contest Carollo’s win on the grounds that the incumbent hadn’t truly been living in District 3 but rather in his six-bedroom, five-bathroom, 5,000-square-foot house on Morris Lane in District 2. Though Leon’s attorneys submitted cell phone records and minuscule electric bills as evidence, a judge ruled in Carollo’s favor.

Russell, meanwhile, intends to use Friday’s meeting to propose his own redistricting map, which would set natural boundaries around Coconut Grove at U.S. 1 and Miami Avenue and move portions of higher-density areas, including the Golden Pines area north of U.S. 1 and west of SW 27th Avenue, to other districts.