Audio By Carbonatix

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation commissioners unanimously voted Wednesday in favor of reviving controversial black bear hunting and approved rules for future hunts, including dog-hunting teams, baiting, and archery. This will be the first black bear hunt in Florida since 2015.

The FWC estimates that there are about 4,000 black bears in the Sunshine State, up from several hundred in the 1970s.

Proponents of the hunt argue that black bear encounters have become more and more common in recent years, and a regulated hunt will keep their population in check, decreasing unwanted bear-human encounters. But the move, voted on at a Wednesday commission meeting in Havana, Florida, seems to fly in the face of public opinion, with a majority of the 168 people who signed up to speak arguing the specific December hunt, and black bear hunting in general, is inhumane, unnecessary, and designed to cater to hunters and real estate developers.

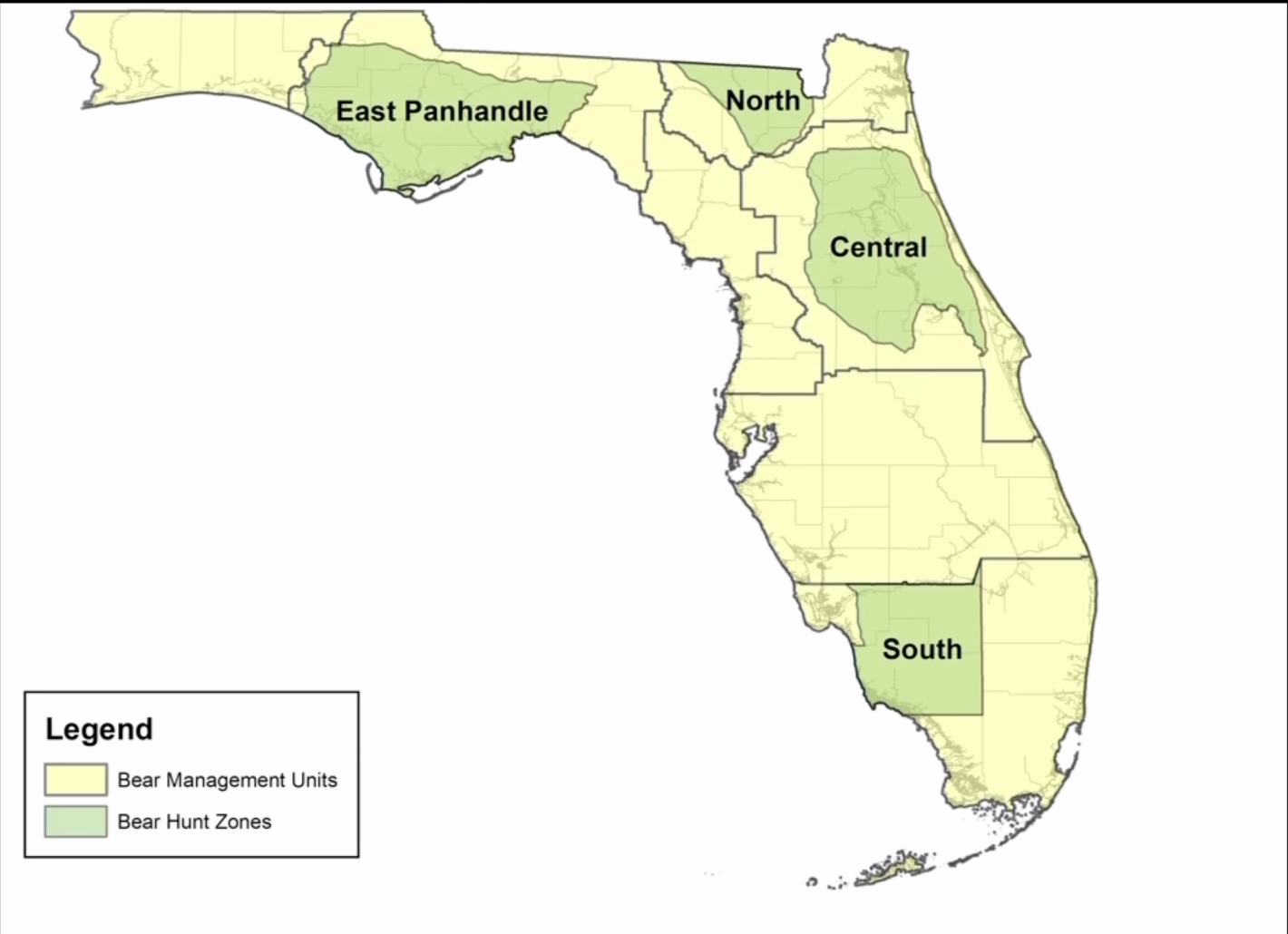

The FWC, whose mission is “managing fish and wildlife resources for their long-term well-being and the benefit of people,” is set to issue 187 black bear hunting permits by random draw for a special, regulated hunt taking place between December 6 and December 28. Applications are $10 each, and licenses for those selected will run $100 for in-state residents and $300 for out-of-state visitors. Each hunter will get one black bear tag, which allows them to kill or “take,” as FWC commissioners put it, one black bear during the hunt. FWC has opened four hunting zones, with the closest to South Florida centered on Collier and Hendry counties, just west of Miami-Dade and Broward counties.

The upcoming December black bear hunt is restricted to four areas of Florida, according to FWC.

FWC

Several commissioners and public officials from counties throughout Florida attended the meeting to voice support for both the hunt and for opening an annual black bear hunting season beginning in 2026.

“We take pride in our natural surroundings and the ability to live with wildlife,” Gulf County Commissioner Sandy Quinn said during the public comment period.

Gulf County is just southeast of Panama City Beach in the Florida panhandle, where Quinn says, “we’re seeing black bears more and more in our neighborhoods and playgrounds.” Other public officials echoed his comments, but none gave any data on black bear encounters.

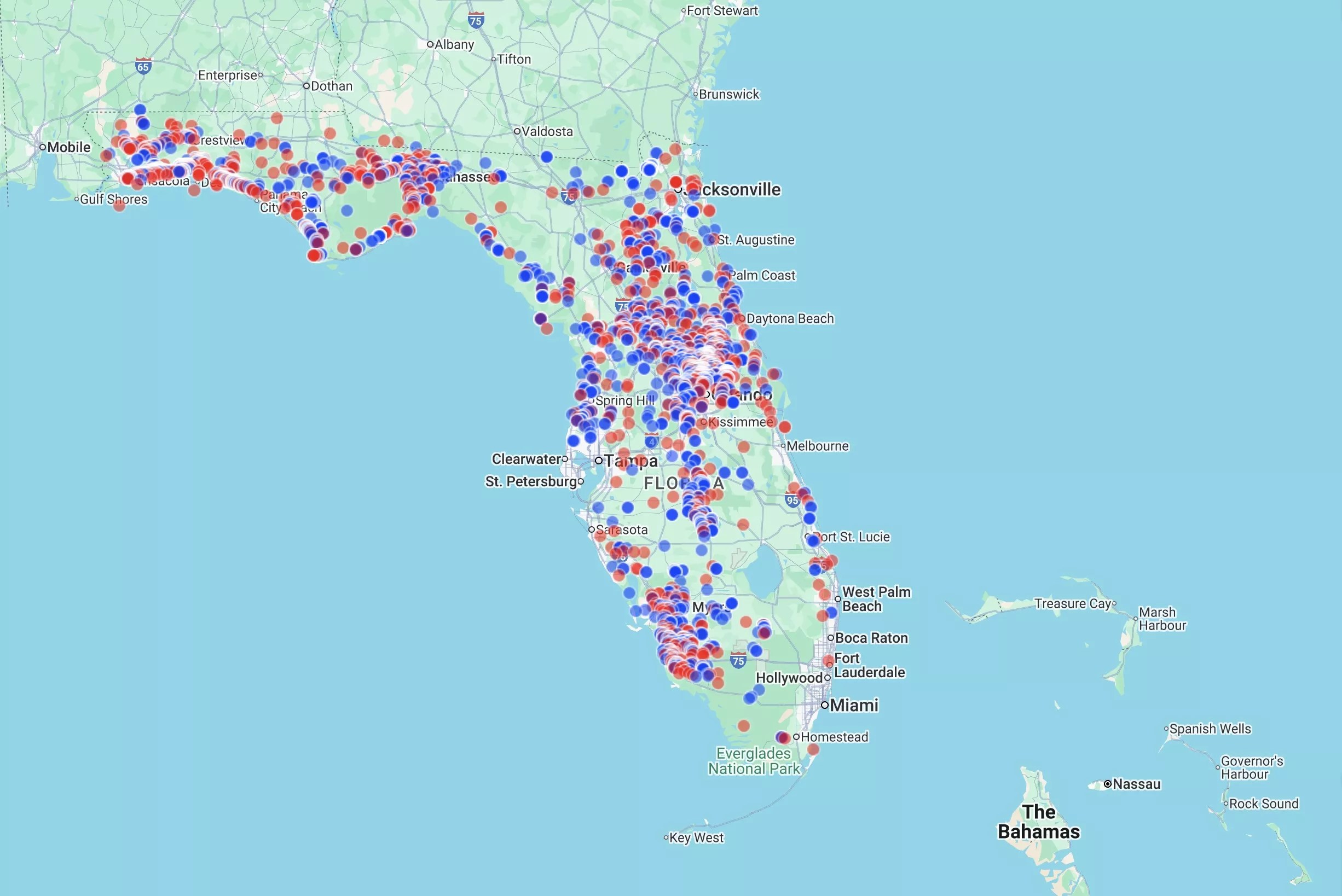

New Times has requested data on statewide black bear encounters with humans, but has not heard back. FWC has a black bear sighting map on its website showing encounters over the past five years, but the underlying data wasn’t available.

Several self-proclaimed hunters donned high-visibility orange shirts and hats to express their thoughts at the Wednesday meeting, making up what appeared to be a slight minority in the crowd. Commenters, who seemed to trust FWC data, focused on the bears’ increasing populations to prove that population control measures are necessary.

One man demanded FWC vote in favor to “keep our cracker Florida heritage alive.”

A majority of commenters, however, seemed adamantly against the proposed hunt and its rules.

“The FWC is an agency that’s lost its vision; protecting wildlife has been replaced by horrible values,” one man said.

Most opponents called the use of hunting dogs inhumane. (The FWC will not allow the use of hunting dogs during December’s hunt.) Wednesday’s vote allows for hunting dogs to be used beginning in 2027, after training next year, according to the FWC.

Multiple opponents argued FWC should instead focus its energies on expanding its annual Florida Python Challenge, when the state offers big bucks for the most Burmese python kills. That hunt is generally celebrated as a fight against an invasive species that, if left unchecked, will continue to kill Florida’s native wildlife.

Opponents of the black bear hunt seem to make up the statewide majority, as well. An FWC survey on the topic found that 75 percent of 13,000 self-selected participants opposed the hunt, with just 23 percent in support, according to reporting by Florida Phoenix. Surveys from the University of Central Florida and Remington Research Group seemed to agree, with 75 percent and 81 percent of respondents opposing the hunt, respectively, according to the Tallahassee Democrat.

“The weird thing about this is they’re supposed to complete a black bear population study in 2030,” Bear Defender founder Adam Sugalski previously told New Times. “So, we’re perplexed at why they’re doing this in the middle of the study.”

Despite the advocacy group’s concerns, FWC touts successful conservation efforts that helped restore black bear populations from several hundred in the 1970s to more than 4,000 today. According to a statement on its website, the commission’s objective is to “balance species population numbers with suitable habitat and to maintain a healthy population.”

Opponents, however, argue the motive behind the hunt is economic, not ecological, says Melanie Oliva, a local animal advocate and occasional New Times contributor. Oliva and Sugalski disputed the notion that black bear encounters are becoming more prevalent because their populations are growing.

They argue the state’s growing population, which puts Florida at or near the top of nearly all state growth lists, is pushing human development into black bear habitats. The encounters most often occur in central and northern Florida, Sugalski tells New Times.

FWC’s black bear sighting map shows encounters over the past five years, but the underlying data wasn’t available.

“People are moving into neighborhoods right next to the woods and then leave their trash out and wonder why they’re seeing bears,” Sugalski previously told New Times. “Bears aren’t going to change their behavior because you moved into their home.”

Sugalski says he fears the FWC doesn’t care how many black bears are killed in December because, unlike the last FWC-approved hunt in 2015, there will be no check-in stations to count the number of bears killed. In 2015, there was a 304-bear limit for the weeklong hunt, but officials had to call off the hunt early after 298 bears, including lactating females, were killed in 48 hours.

At Wednesday’s meeting, FWC officials said physical check-in stations are unnecessary owing to technological advances and that the agency lacks resources to run them statewide.