Courtesy of the South Florida Sun Sentinel

Audio By Carbonatix

In the year prior to his death, the South Florida Sun Sentinel published a profile about Leicester “Les” Hemingway. There was no mention of his failing health, just a fluffy firsthand account of his life on Bimini. Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother had been coming to the island for most of his adult life, beginning at the age of 19 when he built himself a sailboat and singlehandedly found his way from the Atlantic coast of the U.S. to the Bahamas.

Bimini was a place where he could be himself. Sure, years after that first visit in 1934, his famous brother would make a splash there – legend was Ernest would fight anybody who asked for it – but Bimini was Les’ territory. Still, there were moments when people were confused. Sixteen years separated the brothers. The resemblance between them was somewhat uncanny, though; they both had beards, barrel chests, and spectacles. It was as though Les were the ghost of his brother, haunting subtropical beaches.

The reporter writing the profile recounted how, prior to their 1981 takeoff from Fort Lauderdale to Bimini, a young man approached Les. “Hey, you look familiar,” the young man said. “Don’t I know you from somewhere?”

“Maybe,” Les responded, then extended his hand. “Jack Dolan. U.S. Marines.”

The young man walked away befuddled.

“I tell them I’m Jack Dolan because I get tired of telling people I’ve changed my name from Tolstoy,” Les deadpanned.

Perhaps the young man thought he’d just met a 20-years-dead Ernest Hemingway, or maybe he’d seen Les in the South Florida papers before. He was famous, too. After all, he’d once been president of a micronation.

New Atlantis was no amateur act of Caribbean colonialism.

Courtesy of Anne and Hilary Hemingway

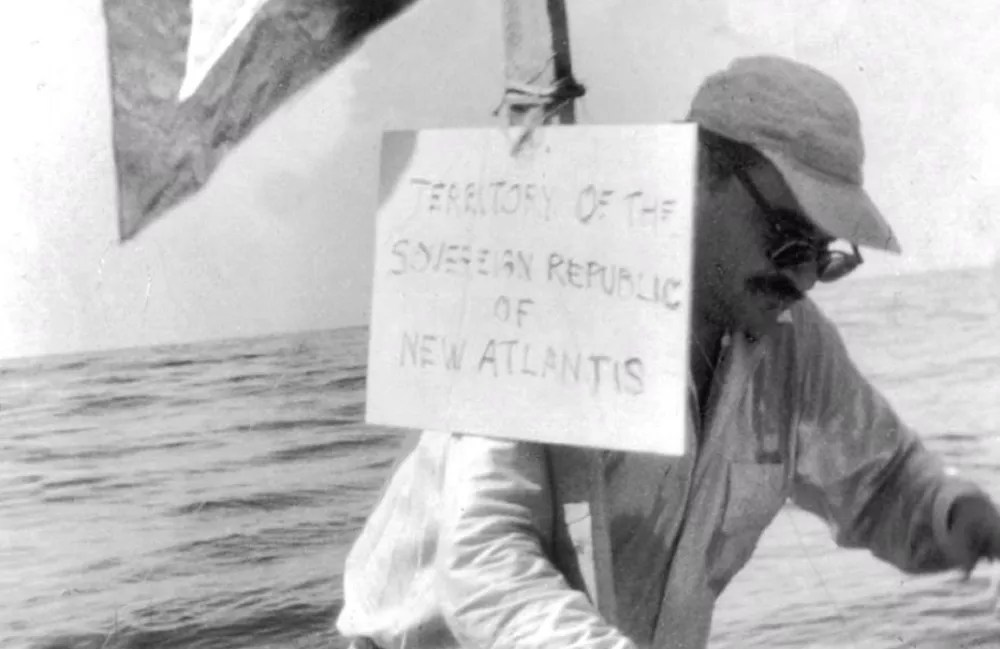

Founded in 1965, New Atlantis was located on a bank six and a half miles off the southwest coast of Jamaica. Its exact coordinates were latitude 18 degrees, 1 minute north and longitude 78 degrees, 4 minutes west. Les Hemingway was founder and president. Consisting of a bamboo raft, iron pipe, steel cable, and stones, the terraformed nation rose from a sea depth of 50 feet. Les’ wife, Doris – “The Betsy Ross of New Atlantis,” as he called her – stitched together a quick flag, navy blue with a golden triangle pointed downward, out of sailcloth. She was First Lady, and his daughters, Anne and Hilary, received ladyships as well.

This was no amateur act of Caribbean colonialism. Les claimed the sandbar under the Guano Islands Act, an 1856 federal law stating that islands with seabird or bat excrement deposits on them could be claimed on behalf of the United States, so long as they are in international waters. Les split New Atlantis in half between U.S. jurisdiction and the Republic of New Atlantis. There was no bat poop on the bamboo raft until he brought it there himself.

In an attempt to legitimize his fledgling, buoyant micronation, Les issued currency and stamps, set up a series of P.O. boxes, and sent letters to President Lyndon Johnson from New Atlantis. Unto Lady Bird Johnson and her daughters, he bestowed the fabricated honor of “Order of the Golden Sand.” The president replied to Les’ correspondence, addressing the younger Hemingway as president of New Atlantis. In the world of micronations, this is seen as international recognition.

The Republic of New Atlantis, founded by Ernest Hemingway's brother, was located on a raft. https://t.co/xujjQhLaby pic.twitter.com/uwHYn7atOl

— Brendan I. Koerner (@brendankoerner) January 18, 2016

In a press release declaring the micronation’s sovereignty, Les wrote, “Right now the capital city of New Atlantis is Coconut Grove, Florida, a section of Miami that considers the entire remainder of Dade County as one vast, philistine suburb.”

Today, of course, the same neighborhood is nearly unrecognizable to Anne Hemingway Feuer, Les’ eldest daughter. Nearly 40 years after her father’s death by suicide in 1982, Anne sits at a concrete picnic table in Coconut Grove’s Regatta Park. It’s an abnormally blustery “winter” day. The new highrises nearby block out what little sun there is.

Anne is hovering over a scrapbook of her family’s history, protecting it from the threatening rain. Despite the weather, she carries on with her storytelling. To a waterfront fable, she’s no stranger.

“We lived on a sailboat right there in Dinner Key Marina,” she says, looking toward Biscayne Bay. “We also lived on one in Bayfront Park in downtown Miami. Dad would buy boats, repair them, then sell them, and we’d move.”

Anne is the eldest of two daughters raised by Les and Doris Hemingway around Miami and the tropics. Her mother used to brag that Anne had been to 11 schools by the time she was a teen. It was an itinerant lifestyle, one that Anne doesn’t reconsider too often. “I keep these memories locked up in a back part of my brain,” she says. Though, when asked about her time as a member of the first family, she straightens her back and puts on an air of regality. The Hemingways weren’t the first family but they certainly took themselves seriously.

“I was Lady Anne Elizabeth Jane Hemingway,” she says, referring to the symbolic titles bestowed unto her by her dad.

Les’ daughters recall how he hawked citizenships to New Atlantis in a variety of now-closed Miami bars. In exchange for an investment in his country, he offered up official titles to lotharios and stewardesses alike, almost like an early version of trading clout. Tragically, though, as the story goes with many acts of confidence artistry, the fall came as abruptly as the rise.

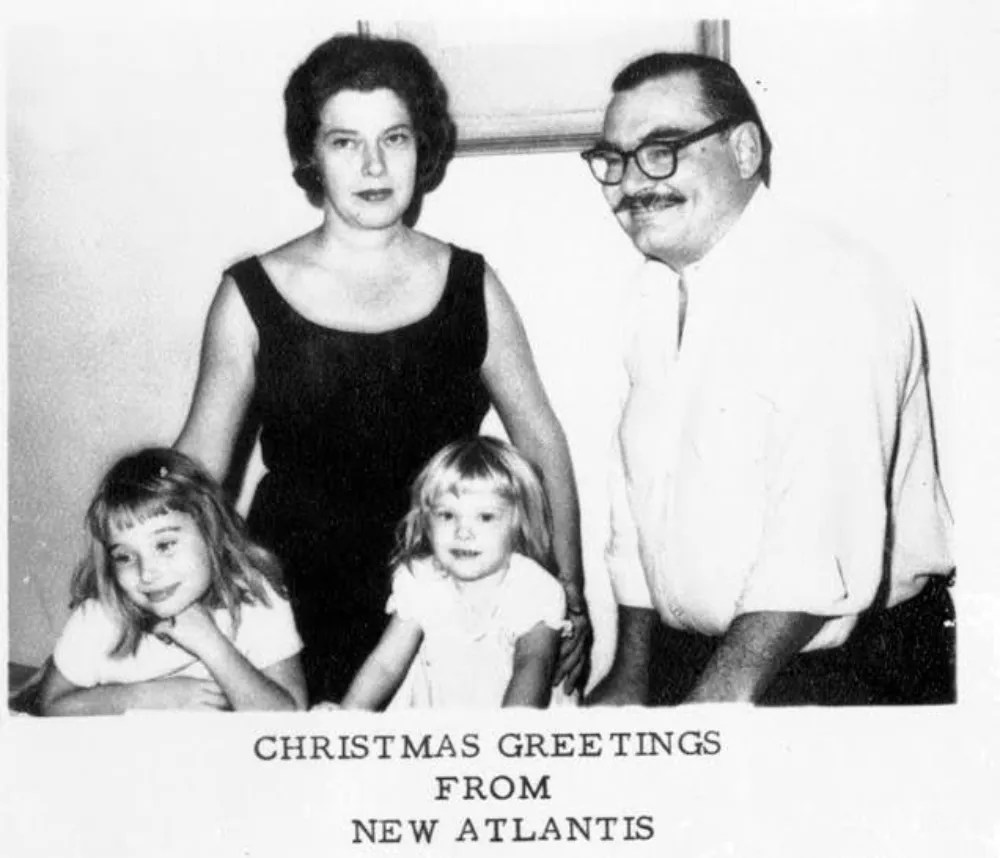

Doris and Les Hemingway raised their daughters, Anne and Hilary, in Coconut Grove, the capital of New Atlantis.

Courtesy of Anne and Hilary Hemingway

In its first year of operation, a tropical storm swept the fledgling dream nation out to sea. It turned out that a country fashioned entirely of bamboo shoots and rusting drain pipes was not sustainably conceived. Still, 15 years later, in newspaper blurbs, Les hadn’t given up on New Atlantis, speculating that it was “probably floating somewhere near Haiti.” Though the micronation ceased to exist, it remained affixed as a badge on Les’ legacy. And he had many more to collect.

The Hemingways bopped around various Coconut Grove homes, including one where they kept a pet raccoon, but finally settled into a house at 11 E. San Marino Dr. on Miami’s Venetian Islands in 1965. They purchased it using the last of the funds from Les’ 1962 biography of Ernest, My Brother, Ernest Hemingway. The book is an endearing portrait of brothers separated by a nearly two-decade age gap whose relationship was forged by tragedy when their father killed himself in 1928. It was the only biography Ernest Hemingway was aware of prior to his death.

In the book, Les, who himself fought in World War II, recounted what it was like being the little brother to a war hero. Ernest had made headlines as a volunteer ambulance driver for the American Red Cross during World War I, earning a Silver Medal of Valor from the Italian government for getting wounded while saving men from Austrian mortar fire.

“It was pretty glorious,” Les wrote. “Being kid brother to the guy who had personally helped make the world safe for democracy.” The book was not only successful in its time but remains the quintessential Hemingway biography today.

As a writer, Les didn’t have many other unalloyed successes. He had publication credits to his name, including a work of autofiction about his World War II experience called The Sound of the Trumpet, but none could earn him a real living.

Grand triumphs and failures were par for the Hemingway men, though – they were true Florida men. In his bio of Ernest, Les wrote of their father, Clarence, who worked as a doctor: “He had been thoroughly clipped in the unforeseen bust of the Florida real estate boom. He had lost his savings that he had invested in land which suddenly had no resale value. The year before he had successfully passed the Florida State medical examinations and he had looked forward to retiring there in a moderate practice. Then this prospect disappeared.”

Ernest’s career had been taking off right around that time. The Sun Also Rises had been published by Scribner’s in 1926, to critical acclaim. He’d sent his dad a check to cover some unpaid bills, but before it could arrive, Clarence died by suicide in the Oak Park, Illinois, home where the boys grew up.

A photo of Dr. Clarence E. Hemingway (top left) and his wife, Grace Hall Hemingway (second from left), with their children, Carol, Ernest (top center), Leicester (bottom center), Ursula, Sunny, and Marcelline in Oak Park, Illinois, circa 1917.

A chip off the old block, Les was not without his own financial troubles. Their last name was associated with glamour, but this set of Hemingways worked hard to maintain that façade. “Dad charmed the previous owner of the San Marino house into giving it to him for a better price,” Anne says. “He could always talk people down like that, and it was important because we didn’t know when his next paycheck would be coming. We wouldn’t have been able to afford the place if Mom didn’t have a full-time job.”

The house, which still stands today, is a 1920s Mediterranean Revival with a curvy, clay-tiled roof and what must be a hundred feet of waterfront. “We’d have dinner parties with Playboy models and doctors, and I’d just be standing there, really shy,” Anne recounts. “Meanwhile, our yard was completely overgrown.”

Anne’s sister, Hilary, looks back on the Hemingway family’s Miami with more fondness than her sister. “We grew up on sailboats, and I still don’t have my land legs,” she jokes.

Where Anne felt more reserved in contrast to the chaos around her, Hilary leaned in. She lived a physical life like her father. Once, she fell out of a tree and broke some bones. She also bonded with Les over his true passion: buying junk boats and rebuilding them. She’d take the small ones on single-handed sailing missions around Biscayne Bay.

“I can track my kids’ whereabouts on my phones now,” she says. “Dad used to put me in a sailboat, give me a dime for the payphone, and tell me to check in when I made it to the next island.”

Hilary inherited the ability to tell a story. She’s co-authored a handful of books about the paranormal with her husband, Jeff Lindsay (yes, the guy who wrote Dexter.) Lindsay, whose father was a professor at the University of Miami, grew up in Coconut Grove, and that’s where his romance with Hilary flourished. In 1998, the couple published Hunting with Hemingway, a sorta-biography of Hilary’s dad.

The book’s conceit is simple. Sometime after her father’s death, Hilary discovered a tape in their San Marino house and set about transcribing it. On the tape, her father regales guests – including the godfather of Miami crime fiction, Charles Willeford – with stories of his hunting adventures with Ernest. Hilary affectionately refers to Willeford as Uncle Charlie and remembers him most “for his good cheer and walrus mustache.”

In between transcriptions, there are interludes wherein Hilary and her husband add color to the tales so that their daughter, Bear, might know her granddad better. Telling Bear about the love for the water she shared with her dad, Hilary wrote, “Sometimes in the evening, Grandpa would have a drink with friends and admire the sunsets over Biscayne Bay. The water was so beautiful in the light from the setting sun – blue-green, streaked with orange…”

In the book, Hilary describes evenings at the San Marino residence. Even if it was hot, she recalls, her dad would light a fire outside. “It was ceremonial,” she says, maintaining that the home was haunted. “The builder, Mr. Hendricks, his initials were LCH, and he died in that house. My dad’s initials were LCH, and he died in that house too.”

One evening, with the outside fire lit, she recalls things taking a turn toward the preternatural. Les and Doris were hosting a séance, and they accidentally summoned a demon spirit. According to Hilary, it communicated with them by sliding their grand piano across the room and appearing briefly in the window, silhouetted by palm trees.

If you ask Anne, she says, “Hilary’s book is really good, but she messes with the truth.” If you ask Hilary about the book, she’ll tell you that there’s an unspoken Hemingway family tradition of blurring the line between reality and fiction.

“We were all truth in the house,” Hilary says. “But since others will just say what they want about our family, the public sphere is different. That’s where we create our own stories.” She is the daughter of a self-proclaimed president, after all.

There’s an unspoken Hemingway family tradition of blurring the line between reality and fiction.

Given that so much is passed down within the Hemingway family – immense physicality, depression, storytelling talents – it’s no surprise that Les and Hilary’s connections to the paranormal can be traced back to Grace Hall Hemingway, Ernest and Les’ mother. “Gracie” had regular conversations with the famous early-20th-century spiritualist Edgar Cayce. Digitized archives of his correspondence confirm that the two communicated. Gracie was hoping the spirit world could help her cure Clarence of physical and financial ailments.

Perhaps it wasn’t dumb luck that had led Les to Bimini all those years ago, but rather a cosmic connection. Cayce, whose quotidian talents were that of a spiritual medium, also spent time writing imagined futures. One of his predictions was that the Lost City of Atlantis would be found in the Caribbean, and he also foresaw that the Bimini islands were mountaintops.

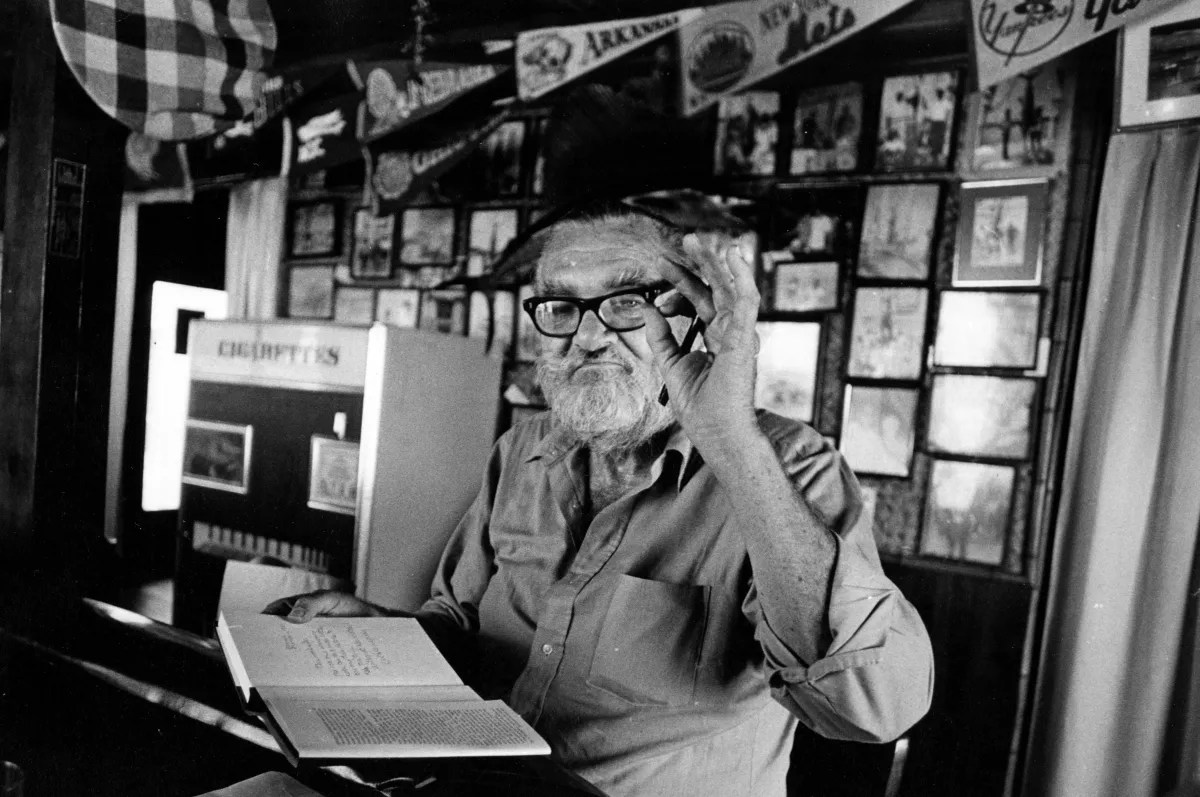

Les Hemingway distributes copies of his newspaper, The Bimini Out Island News, at End of the World Bar in Bimini in 2011.

Courtesy of the South Florida Sun Sentinel

By the 1970s, Les’ explorations of Bimini and its characters were the impetus for him to get on a weekly flight to South Bimini. The flights, usually on a Chalk’s Airlines propeller plane, were often filled with amateur archaeologists and other characters. This explains how Les ended up in a Cessna over the Gulf Stream with Jim Richardson and J. Manson Valentine in 1972.

The former was a Bimini hotelier, the latter a writer and authority on the Bermuda Triangle and Atlantis. Hilary says her dad and Richardson even brought along a dowser – a practitioner who divines hidden water sources using L-shaped rods that operate on ideomotor responses – to help them try to identify ancient freshwater sources. The team of adventurers sighted the famous Bimini Road and began other explorations of the island.

In 1980, just a few years before his death, Les appeared alongside Hilary in an episode of In Search of…, a paranormal-focused television series broadcast on A&E and hosted by Leonard Nimoy. The episode was called “The Bimini Wall.” The crew all got in a boat, and Les led them over to the Healing Hole, a freshwater spring hidden in a mangrove swamp on North Bimini. Les believed the Healing Hole was not only evidence of Atlantis, but that it had very real curative properties. Hilary, then a teenager, didn’t bat an eye trudging through the muck.

Knowing that Les would take his own life in two years, it’s a beautiful scene – father and daughter in the Healing Hole, hopes high. Hilary maintains that her mother’s psoriasis was cured almost instantly after a dip in those waters. Even today, Anne expresses a desire to visit the waters to cure some ailments of her own. Both sisters agree that the Healing Hole cured their father of his gout.

There are other incredible pieces of Les lore. The sisters Hemingway recall that one of their dad’s boats was used as an explosion dummy in the James Bond film Thunderball. “The boat was a 70-foot captain’s launch Dad had purchased from the U.S. Navy after World War II,” Hilary says. Neither sister can remember with certainty the name of the boat, but Hilary believes it was called the Sea Dawn. “My mom used to joke about that boat,” she says, “That it was called that name because it would never see another dawn.”

History supports that Les would have had a line on World War II-era boats. After all, he played his part in the effort. Before serving in the army and not long after his first sailing trip to Bimini, Les co-wrote an article called “Caribbean Snoop Cruise” with one Anthony Jenkinson for the November 1940 edition of Reader’s Digest. A map contained within the article traces the journey of their 12-ton schooner, the Blue Stream. World War II was on the verge of breaking out, and rumors of German U-boats in the Caribbean were swirling. “President Roosevelt announced that an unidentified sub had been sighted off of Miami,” Les wrote. “Back of all these rumors, we thought, there must be a good story.”

The sailors heard that Nazi spies hid in tropical ports of call, so they made excuses to pop in unannounced. According to Les, with tensions on the rise, one could not just lay about. “International law requires a vessel to sail to its declared destination without casual stopovers,” he wrote. “The sudden storms of the Caribbean gave us a real excuse for popping into places unannounced. We had other excuses too. We drove a block of mahogany into one of the cylinders of our auxiliary engine, and thus had ‘engine trouble’ whenever we needed it.”

Les and Jenkinson sailed all over the Caribbean, exploring its most isolated Western portion, including the Mosquito Coast near Nicaragua. “In Limon, Costa Rica, we were shown a storehouse owned by a German,” he wrote. They suspected it of being a Nazi fuel storage facility. “Limon’s largest hotel is German-owned. There we felt we were in an outpost of the Greater Reich.” With Ernest’s help, Les was able to get the message across to powers in the U.S. government that Nazis and their supporters were scattered throughout the Caribbean and posed an immediate threat to the Panama Canal.

Many at the time questioned whether Les ever did find Nazis in the Caribbean and whether he’d been involved in legitimate spycraft, as he claimed, but in the context of his life’s events – from a presidency to the paranormal – the story warrants further investigation.

In his later years on Bimini, Les distributed his own publication, The Bimini Out Island News. It was the final expression of his career as writer and journalist. He’d previously had a regular column in the Miami Herald in which he wrote about the sport of jai alai, waxing passionate about the physicality of the peloteros.

His fascination with the high-flying athletes was perhaps an expression of his own failing health. Les had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, and his doctors told him that his legs would have to be amputated. Rather than undergo that surgery, he chose to take what Hilary refers to as “the family exit.”