Illustration by Pete Ryan

Audio By Carbonatix

David Yuzuk’s police radio blared from his shoulder as he leaned against his patrol car outside Boston Market in Aventura. Palm trees swayed gently in the humid air while he waited for his friend Richard Flaherty. It was around 6 p.m. on a weekday, and the cop was just starting his dinner break.

For two weeks, Yuzuk, a 46-year-old Brooklyn native with a striking resemblance to comedian Rob Riggle, had been sharing meals with Flaherty, a four-foot-seven homeless Vietnam veteran whose lined forehead and bushy eyebrows made him look older than his 69 years. They had known each other for more than a decade, but Yuzuk had only recently learned Flaherty’s backstory, a tale of international intrigue that seemed too incredible to be true.

As it turned out, the diminutive man who slept underneath a palm tree outside Publix was a former Green Beret captain with a trunk full of Purple Hearts and a Silver Star. The revelation stunned Yuzuk, who was so moved he decided to make a documentary about Flaherty’s life.

That evening in May 2015, Flaherty hopped off the bus a few minutes late, his graying mustache peeking out from beneath the floppy bucket hat covering his bald head. Inside the restaurant, the two men grazed on chicken legs and sweet potatoes while Flaherty described his early life and military heroics for Yuzuk, who jotted down notes.

With Yuzuk’s dinner break winding down, the men said goodbye with a handshake – a sign that Flaherty, who was arthritic and sensitive about his small hands, trusted the cop. But then the homeless man went off on a strange rant. “These State Department guys are following me around,” he said, almost too casually, “and you’re one of them!”

“Rich, what are you talking about?” Yuzuk said. “I’ve known you for years.” With that, Flaherty seemed to calm down. He waved goodbye and walked off, while Yuzuk, baffled, left to finish his shift.

“I thought this was just a story about a Vietnam vet… It was like, what rabbit hole did I just step into?”

Neither man knew the long span of their slow friendship was about to come to a screeching halt. Within a week, Flaherty would be dead, his body found bloodied and battered in a manicured median blooming with drift rose. And Yuzuk would soon learn the small soldier’s incredible life was far stranger than he ever could have imagined.

Inside a four-by-four-foot storage unit rented in Flaherty’s name, the officer uncovered Arabic-language tapes, psychiatric reports, and a U.S. passport, which showed that a man who had been homeless for 27 years had recently traveled to Iraq, Cambodia, and Venezuela. He’d even had his own travel agent.

Yuzuk’s interviews with Flaherty’s loved ones were no less confusing. Relatives said he had a history of deep-seated paranoia and had long spoken of dangerous “enemies.” They were shocked to learn he had refused burial at Arlington National Cemetery, asking instead to be laid to rest in a plot in rural West Virginia, next to a woman they had never heard of.

A consummate cop, Yuzuk had always believed extraordinary accusations needed extraordinary proof. But the more he uncovered, the more he wondered whether the tiny man who’d been overlooked for years could have secretly been working as a government contractor, a mercenary for hire, a black-market gunrunner – or even a spy with the perfect cover story.

“I was blown away,” Yuzuk says. “I thought this was just a story about a Vietnam vet with PTSD living on the street. It was like, what rabbit hole did I just step into?”

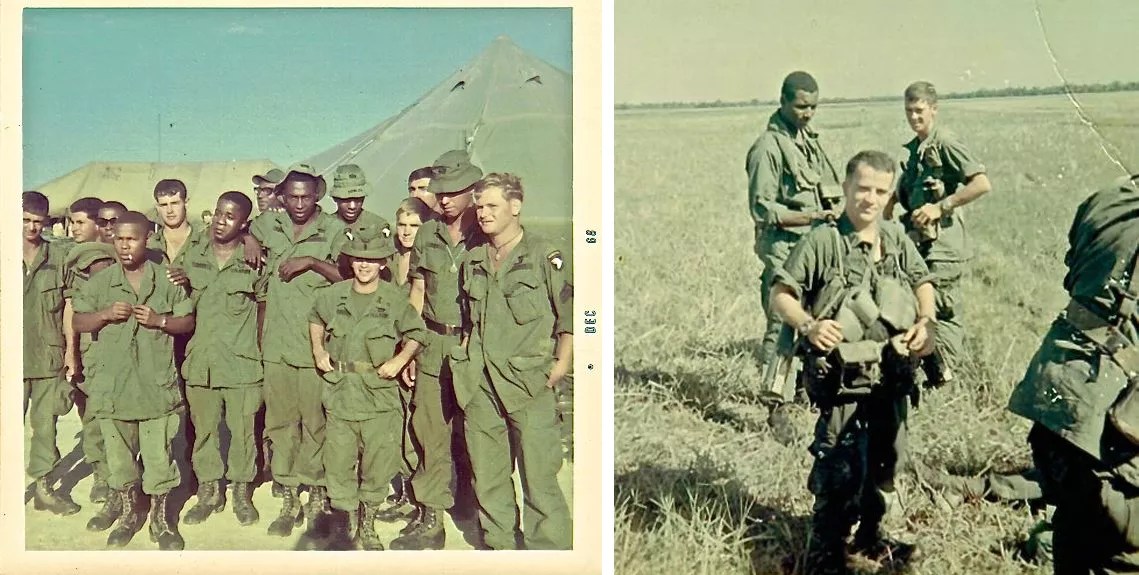

Richard Flaherty served two tours in the Vietnam War after receiving a special waiver exempting him for his size.

Photos courtesy of David Yuzuk

From a young age, Yuzuk was fascinated with people whose lives were different from his own. So perhaps it’s no surprise he’s the one who would finally unravel the twisted strands of Flaherty’s life story.

The younger of two boys, Yuzuk was raised by Jewish parents in a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood. His father worked as a substance abuse prevention counselor in New York City schools, while his mother stayed home with the children. His maternal grandparents, who immigrated to New York from Israel after escaping a Siberian concentration camp during the Holocaust, lived in a spacious apartment in Brighton Beach, about a half-hour away.

Yuzuk was a scrawny, serious kid who played baseball on the weekends on a team his dad helped to integrate. “When we belonged to little league, it was all white people,” says Neil Yuzuk, his father. “Myself and a couple of other people said, this is wrong. I was not raised with prejudice, and my kids were not raised with prejudice.”

Yuzuk was 11 when his parents divorced and his dad moved out of the family’s home. Before the boys left for school each morning, their mother commuted two hours to work as a bookkeeper in the garment industry. By his own account, Yuzuk was “a troubled 14-year-old kid” when he entered high school, but he soon found his niche on the football team, where he excelled.

He graduated with a football scholarship to Stony Brook University but dropped out after injuring his shoulder during his freshman year and became a bouncer. It was fun at first, but over time he worried about how much he was starting to crave the violence. “I went to real rough, rough places and became a real rough person,” he says. “But I was self-aware enough to know I needed to get out.”

At 21, Yuzuk took a job with a trucking company looking for someone to work out of Opa-locka. “Everyone down here said it was a bad neighborhood, but I came from Brooklyn,” he says. “It was beautiful. There were palm trees.”

He let Yuzuk in on a secret: Long before he was homeless, he’d done two tours in Vietnam.

Yuzuk didn’t find his calling until his early 30s, when he went through the police academy. He first took a job in Surfside but transferred to the Aventura Police Department in September 1999.

He loved police work, but it left him wanting to try something different in his off-time. So Yuzuk began acting, winning bit roles as a cop on TV shows such as Burn Notice and The Glades. He even co-wrote a feature-length crime drama set in Miami with a friend who went to film school.

All of that creativity needed an outlet, and shortly after taking the job in Aventura, Yuzuk met the man whose mysterious life would eventually fulfill that need. All the cops in the small town knew Flaherty, a constant, friendly presence who trekked all over town wearing his backpack and khaki bucket hat. Yuzuk first bumped into him at the movie theater inside Aventura Mall, where the cop worked off-duty security. Flaherty was a regular on Tuesdays, when tickets were discounted for seniors. Over time, their polite nods turned into hellos and short conversations.

For 15 years, that’s as far as their relationship went, until Yuzuk changed things forever with a simple question. One day on patrol in April 2015, the cop spotted Flaherty near his palm tree at the corner of Aventura Boulevard and NE 29th Place. Yuzuk asked him about a rumor floating around the department: namely, that Flaherty was spectacularly rich. “I heard you were a millionaire,” Yuzuk said.

“Yeah, I’m a real fucking millionaire,” Flaherty shot back. “I just like it out here.”

The men laughed, but the wisecrack opened something up in Flaherty. He paused and then let Yuzuk in on a secret: Long before he was homeless, he’d been a platoon leader in Vietnam. More incredible, he said he’d been a captain in the Green Berets, the Army’s elite special forces unit.

Yuzuk had encountered plenty of mentally ill street people with grandiose delusions, and he found it hard to imagine this small, scruffy character as a highly trained Rambo running amok in Vietnam. But as he drove away, his investigator’s instinct kicked in.

After work, Yuzuk sat at his kitchen computer and began digging into Flaherty’s past. To his shock, he quickly confirmed the basic story: Flaherty had indeed served as a captain in the Army.

Yuzuk couldn’t wait to meet Flaherty again. The next day, he took the homeless man out for lunch, hoping to pry more information from him. After a couple of talks, a crazy idea took hold: Yuzuk asked Flaherty’s permission to make a documentary about his life. Although he’d never done one before, he figured he could shoot a few interviews, do a rough edit, and then throw it on YouTube for some of his friends. The plan was to connect Flaherty to some services, maybe get him off the street.

Yuzuk’s cop buddies were skeptical. Some had heard Flaherty had once been arrested for drugs, while others just couldn’t see why Yuzuk was so interested in a random homeless guy. But eventually, people seemed to come around. Yuzuk sank $20,000 of his own cash into the project, connected with local filmmaker Jeremy McDermott, and began crowdfunding online. His dining room table filled with piles of paperwork and war memorabilia as he dug into his friend’s life.

“I wasn’t looking for a treasure,” Yuzuk says, “but who else can tell the story? His family doesn’t know the story; his friends only know bits and pieces… I don’t feel like I had a choice.”

Richard James Flaherty came crying into the world in a delivery room at Stamford Hospital in coastal Connecticut three days after Thanksgiving in 1948.

He was the second-born child, a fate that doomed him before he took his first breath. Although his mother didn’t know it at the time, her blood type was Rh-negative. Though the condition doesn’t affect firstborn children, it deprives younger siblings of oxygen, making them vulnerable to developmental problems ranging from jaundice to heart failure and brain damage.

“They didn’t know this back then, but he was a result of that,” says Donna Marlin, Flaherty’s cousin. “It affected his height, but it certainly didn’t affect his intelligence.”

It was an inauspicious start for a truly spectacular life. The details of Flaherty’s Army career and his later exploits in South Florida – confirmed by military files, court records, and New Times‘ interviews with Flaherty’s relatives and friends – paint the picture of a fearless man with stores of ambition and natural drive.

Flaherty grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Stamford, sharing a room in the family’s two-bedroom home with his older brother, Walter. Their father, Walter Sr., was a salesman and a shipping clerk for Sears, while their mother, Beatrice, worked for a local department store called Sarner’s.

Just three years apart, Flaherty and his cousin Marlin were inseparable as children. “I always looked up to him because he was so smart,” she says.

By the time he graduated from high school, Flaherty was a full three inches shy of five feet – the Army’s minimum height – and weighed less than 100 pounds, far lighter than military regulations. But after eating six meals per day and enlisting the help of his local congressman, Flaherty obtained a waiver to enter basic training in fall 1966. He graduated from officer candidate school as a second lieutenant and shipped to Vietnam as a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne.

“He never let his stature interfere with his life,” Marlin says.

Flaherty saw horrible things in combat, as he later told mental health counselors.

In 1967, Flaherty was promoted to platoon leader, and his authority was soon gravely tested. The next April, a group of North Vietnamese soldiers opened fire on his men in the Quang Dien district. But, as vividly detailed in an Army citation, Flaherty knew just what to do. Running out into the spray of bullets, he unleashed a rifle team and launched an attack on an enemy bunker, enabling his men to gain the upper hand.

That “extraordinary heroism” earned Flaherty the Silver Star, the military’s third-highest award for bravery in combat. He returned home and entered the Army’s Special Warfare School, where he graduated into the elite Green Berets. Flaherty then shipped back overseas to Thailand in the fall of 1969, according to military records.

By the time he was discharged in 1971, records show Flaherty had earned a Bronze Star, at least two Purple Hearts, a National Defense Service Medal, and a Combat Infantry Badge. He escaped the war with just a few physical injuries, including a small head wound left by a grenade fragment.

His mental scars cut deeper, though. Flaherty saw horrible things in combat, he later told mental health counselors. He watched as land mines blew off his friends’ skulls and split open their stomachs. He vividly recalled picking up the severed thumb of a soldier who’d lived through an explosion. On one occasion, he came across a young Viet Cong fighter in a spider hole and saw her brains spilling out of her forehead. Nearby, he found a ziplock bag holding her lipstick and perfume.

“This humanized the enemy, cutting my effectiveness as a leader in half,” he later wrote in an application for government disability.

After returning home in 1971, Flaherty moved to New York, where he met Jyll Cohn, a stunning 21-year-old with green eyes and a head of curly blond hair. Best of all, she stood a full inch shorter than he did. Flaherty asked Cohn to be his bride, but her father was insistent that his daughter marry another Jew.

The couple sought solace in South Florida, where Cohn found work as a cocktail waitress and Flaherty studied finance and psychology at the University of Miami. But on March 4, 1975, their star-crossed love came to an untimely end. Buzzed and recently diagnosed with manic depression, Cohn plowed her 1972 Chevy Vega into a metal utility pole on NE 163rd Street at 80 mph. No one could say for sure if she had meant to.

Her death devastated Flaherty, who would never marry or have children. After the crash, he began guzzling two bottles of red wine a day. Legal troubles soon followed.

That November, he was arrested for the first time, accused of carrying a concealed weapon. He avoided a conviction and found work at a local Volkswagen dealership. But soon after, he was busted again, for selling cocaine in Pinecrest.

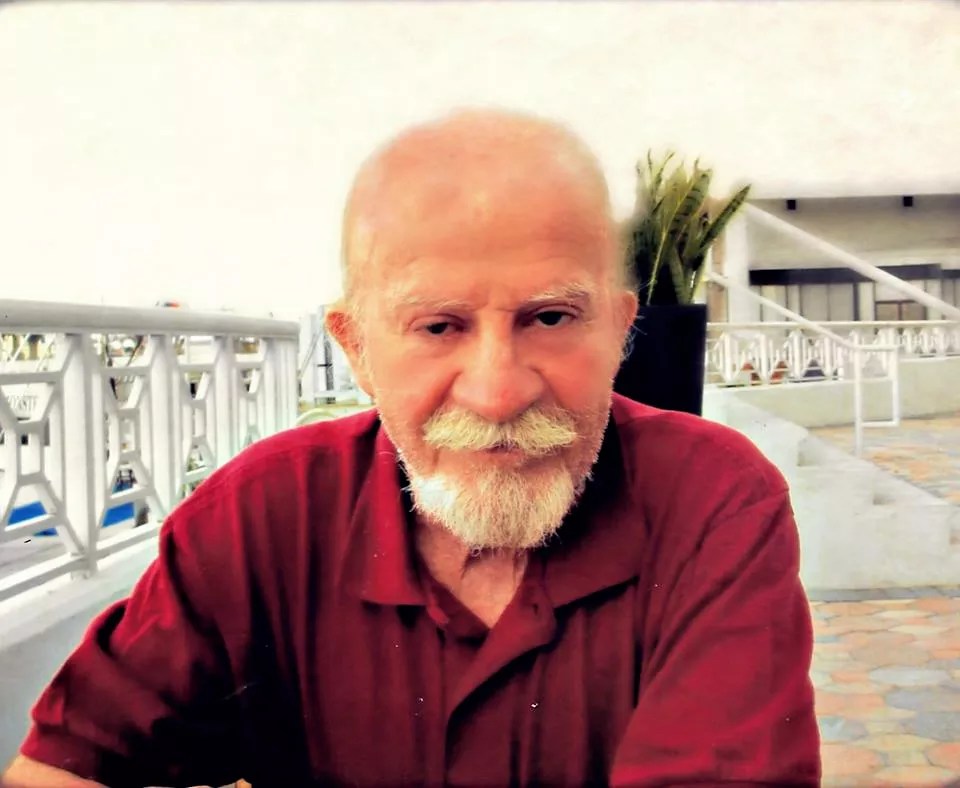

In later years, Flaherty became homeless and slept beneath a palm tree in Aventura.

Photo courtesy of David Yuzuk

Somehow, Flaherty still found a job sorting mail at a post office in 1981. But there were signs he was unraveling. Marlin was visiting on vacation one evening a few years later when he placed an Uzi on the kitchen counter and pointed it at the door, giving her strict orders: “If that door opens and it’s anybody but me, pull the trigger.”

Frightened, she asked her cousin what he meant. “He raised his voice and told me: ‘Just do what I tell you to do. Don’t ask me any more questions,'” Marlin recalls.

Flaherty’s instincts weren’t completely irrational, though. What Marlin didn’t know was that Flaherty had been busted by the feds for selling silencers to an undercover ATF agent. The feds let him walk under one condition: He’d have to work as a confidential informant in a case against two crooked Green Berets.

The sting began just after midnight August 15, 1984, as Flaherty paced the room inside a dumpy motel in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The feds had given him $3,000 to buy a truckload of stolen military explosives, which the soldiers were selling on the black market. Master Sgt. Keith Anderson, who served at nearby Fort Bragg, came to Flaherty’s motel room and motioned for him to step outside. Inside a white Volkswagen van, he showed Flaherty the goods: 96 pounds of C-4, TNT, and military-grade dynamite.

The whole exchange was a trap. Seven weeks later in Vero Beach, federal agents busted Anderson with a Budget rental truck filled with 4,600 pounds of stolen explosives and ammunition. The case made national news and ended with Anderson and his codefendant, Byron Carlisle, sentenced to 40-year prison terms in 1985.

Flaherty was a natural at undercover work, but the gig clearly worsened his struggles to readjust to civilian life. Although he hid it well, Marlin noticed a difference. “He wasn’t taking pills and swinging off chandeliers, but the war affected everyone,” she says. “It’s just that some people can handle it better.”

In December 1986, Flaherty began to believe people were following him, people he claimed had tried to kill him more than twice. “They were never arrested,” he told a psychiatrist, according to medical records. “They have some connections in D.C. They tried to murder me because I was able to make a lot of money for some people.”

By the next year, Flaherty stopped showing up at work. He later told a psychiatrist why: “I needed to get out of town because someone was after me,” he insisted.

Whether Flaherty’s paranoia had grown untenable or his gunrunning contacts really were after him, by the end of 1987, Flaherty was homeless. He set up camp beneath a palm tree on the side of Aventura Boulevard. By all appearances, the former war hero became just another transient. He slept outdoors, bathed in public restrooms, and became a regular at Publix. His life looked simple, if sad.

For decades, Flaherty kept to himself. Although it probably would have gotten him better treatment, he never told cops, store owners, or movie theater employees that he was a decorated vet. He spoke occasionally with his cousin Marlin but grew estranged from his older brother. He had no close friends in Aventura.

And then, in the spring of 2015, Flaherty abruptly opened up to Yuzuk. For several weeks, the pair met almost daily as Yuzuk pushed him to recount his history chronologically, in the same methodical way he’d done in countless police investigations.

Flaherty let the cop in on another secret: the unit he kept at Aventura Xtra Storage. Flaherty began unlocking it nearly every day, rummaging around for paperwork and old photos to show the Aventura cop.

Still, Flaherty’s openness had limits. When Yuzuk asked about the undercover ATF case, he froze. “It’s going to be dangerous for you and me,” he warned Yuzuk.

But Yuzuk couldn’t help but dig deeper. On May 8, 2015, he cold-called Fred Gleffe, the retired agent who had organized the sting.

“Eight hours after I talked to Fred, I found out Richard was dead,” Yuzuk says. “Here’s Richard telling me: ‘Do not look into this thing; don’t contact anybody because it could be bad for our health.’ And I contact Fred, and he gets killed.”

Just after midnight May 9, 2015, 60-year-old Leslie Socolov was heading home to the 17-story building that towers over the spot where Flaherty slept each night. The 14-year stenographer with the Miami-Dade Police Department was just a block from her condo when her car hit something. She didn’t stop.

The next morning, Socolov passed a yellow tarp in the intersection, covering what looked like a body. At work, she plugged the street names into Google and learned that a Vietnam veteran named Richard Flaherty had been killed in a hit-and-run. A few hours later, she turned herself in to Aventura Police.

The news devastated Yuzuk. His friend was gone. And his documentary was up in the air. The cop would have to fill in the blanks of Flaherty’s life story on his own – and he soon realized he had greatly underestimated the number of head-spinning questions he would confront about what Flaherty had been up to all those years on the streets of Aventura.

The first mystery presented itself almost immediately. Flaherty had left a baffling burial request, paying a $3,000 deposit long before his death for a plot in West Virginia. Specifically, he wanted a space next to a woman named Lisa Anness Davis.

Flaherty’s family was perplexed – they’d never heard of Davis or the tiny town of Milton. Yuzuk found one hint in a letter Flaherty had written Davis’ sister in 2008.

“I’ve been in love with Lisa for thirty-three years,” Flaherty had typed out in his signature all-caps. “I will be in love with her for the rest of my life on this plain [sic] and beyond, for death will never separate my love for her.”

Yuzuk tracked down Davis’ sister, but she didn’t know about the relationship either. After hanging up, Yuzuk called the man listed in Davis’ obituary as her “loving companion of 15 years,” but he insisted she had never mentioned Flaherty.

“He said she’d always had a place in her heart for vets, for helping people, and maybe that had something to do with it,” Yuzuk says.

In the end, Flaherty’s burial wishes were just another dead end. Although his family wanted him to go to Arlington National Cemetery, they respected his final request. On June 10, 2015, he was buried with military rites in West Virginia.

Flaherty was finally at rest, but Yuzuk refused to let his story die with him. The officer had always known Flaherty wasn’t like other homeless people, but as he ran down more leads, he realized Flaherty’s peculiarities didn’t end with his refusal to panhandle or to stay at a shelter.

For starters, Flaherty didn’t die penniless. By his own account, he was earning just $376 a month in government benefits, but old receipts stashed in the storage unit showed he was regularly wiring money to someone in Thailand. Bank statements also revealed he had thousands of dollars in stocks and bonds. And after his death, Marlin was stunned to learn her cousin had left her a sum of money equaling a modest annual salary.

The strangest clue of all, though, was sitting in the back of Flaherty’s musty storage unit. Yuzuk stared in shock at the newly discovered passport, which was stamped with recent trips around the globe. Then he found a business card for a travel agent at a local agency. After speaking with the woman and cross-referencing old airline itineraries, hotel reservations, and passport stamps, Yuzuk was able to make a rough timeline of Flaherty’s travels. The purpose of the trips wasn’t apparent, but it was clear he wasn’t jetting to tourist hot spots.

In 2008, Flaherty bought a ticket to Amman, Jordan, a staging area to enter Iraq. But Flaherty’s travel agent told Yuzuk that Flaherty never used the ticket. Other documents showed Flaherty made a three-week trip to Caracas in October 2012 – a date Yuzuk later discovered was just a few months after Venezuela banned gun sales.

Flaherty’s longest trip was a four-month excursion in the summer of 2010, when he flew from Jordan to Thailand to Singapore to Cambodia. On the way back to Florida, he stopped by Marlin’s home for a few days, taking her son out for beers and laughing about how he’d been robbed by a Thai hooker. But he offered only vague hints about the nature of his trip.

“He never was specific,” Marlin says. “He just said he went there because people owed him money and that he had a lot of enemies.”

Marlin can understand why it seems bizarre that Flaherty flew to exotic locales and returned to Florida to sleep on a patch of mulch outside. But she says it didn’t seem out of character for her cousin. “To me, when he called and said, ‘I’m going to Thailand and Cambodia on vacation,’ you just have to know him,” she says.

But other clues unearthed by Yuzuk suggest Flaherty’s travels were more than just the strange hobby of an eccentric man. After all, he’d been gunrunning and buying black-market explosives for the feds. He had elite military training. And as an unassuming homeless guy, he was used to hiding in plain sight. He had nothing to lose.

The more Yuzuk poked around, the greater his suspicions grew. After Yuzuk announced plans for the documentary, another officer told him about a strange encounter he’d had with Flaherty a few years earlier.

“One day he saw Richard walking around with his briefcase, and Richard said that he had to leave the country, that he was going to Iraq, working for the CIA,” Yuzuk says. “Maybe it was a joke to himself, maybe it was a joke to the world, that you guys think of me as just this little homeless guy, but I live a much bigger life.”

Yuzuk decided he couldn’t rule out any possibility, though. “The problem is, if he was doing something legal for the government, I’ll never be able to find out,” Yuzuk says. “And if he was doing something illegal for the government, I’ll never find out.”

A few months after Flaherty’s death, Yuzuk was at least able to settle one part of the mystery. In July, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office said it would not press charges against Socolov. As far as prosecutors could determine, she hadn’t realized she’d hit the homeless man. The medical examiner ruled his death a result of blunt force trauma to the head and chest.

Despite Flaherty’s dire warnings just before his death, Yuzuk now believes Flaherty was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“It was just a bad coincidence,” he says. “The timing was just very bizarre.”

Aventura Police Officer David Yuzuk has been unraveling the secrets of Flaherty’s life.

Photo by Jessica Lipscomb

On a sunny December morning, Yuzuk steps into the crosswalk on Aventura Boulevard where his old friend lost his life.

The intersection looks different – the library where Flaherty banged out impassioned letters to the VA has been demolished and rebuilt, and the Publix where he bought snacks and bottles of wine has also been torn down. Still, it’s hard to imagine that Yuzuk will never again run into Flaherty here.

“Even right now, I’m just picturing Richard walking around with his little bag,” Yuzuk says. “This was his place for 15 years.”

A year and a half after Flaherty’s death, Yuzuk still has mountains of questions about his homeless friend. Though he’s learned much about the mysterious Green Beret in recent months, parts of his life remain frustratingly opaque.

After the hit-and-run, Yuzuk wasn’t sure if he should continue with the documentary. Finding the passport was the first sign that Flaherty’s tale wasn’t just a story about a homeless veteran – and he had to ask himself if he was OK with that.

“I was concerned about, am I going to find a really bad person? You feel a little weird desecrating a hero if you find some ugly shit,” Yuzuk says. “Maybe I’d find answers that I didn’t want to know.”

If Flaherty ever worked for the CIA, the agency won’t confirm it.

But Yuzuk also felt strongly that he owed it to Flaherty to finish the film. “I told him I was going to get the documentary done,” the officer says. “I made the decision to just let the story play out the way it really is and not to bend it or twist it in any direction to protect him.”

The biggest unanswered question is whether Flaherty’s longtime paranoia was legitimate. Was he simply a mentally ill homeless man? Or did he have a real reason to fear for his life?

One fellow Green Beret whom Yuzuk tracked down said Flaherty’s worries can’t be discounted. If he was still involved in smuggling drugs or guns, the State Department absolutely could have been watching him. “If you’re doing something illegal, yeah, you’re paranoid,” Yuzuk says.

And Flaherty certainly didn’t act crazy. Those who knew him in his final years say he was sharp and intelligent and spoke coherently.

The professional mental health documents Yuzuk found in Flaherty’s storage unit don’t answer the question either. In a detailed 2009 psychiatric evaluation, a doctor concluded Flaherty had “grandiose and paranoid delusions, poor insight and judgment.” But at the same time, his cognitive function was near perfect. In a dementia examination called the Folstein test, Flaherty scored just two points lower than the maximum.

The government hasn’t been much help in sorting out the truth either. If Flaherty was ever working for the CIA, the agency won’t confirm it. In an email to New Times, a spokesperson says long-standing policy prohibits the agency from discussing its personnel. The State Department, meanwhile, declined to discuss whether Flaherty was recently under investigation.

Yuzuk still has doubts about whether Flaherty was truly chronically homeless or if it was simply his ingenious way of blending in. Marlin says she doesn’t know why her cousin became homeless or why time and time again he rejected her offers for him to move into her two-bedroom condo in Connecticut.

“I pleaded and I pleaded and I pleaded with him, ‘Why won’t you just come?’?” she says. “He said, ‘Donna, I can’t stand the cold,’ but I don’t think that was it. I think the homelessness really was just part of his freedom.”

Other relatives thought the explanation was simpler, that Flaherty was just mentally unstable. One aunt, now deceased, was so frightened she stopped letting him inside her home.

But Marlin now believes her cousin was telling the truth about being followed and needing to confront his enemies. She thinks he might have been recruited as a mercenary. “If Richard had to go out and kill somebody, he would do that,” she says.

Now that he’s gone, Marlin wishes she had pushed him for more information about his trip to Thailand and Cambodia in 2010. “David and I have been trying to put this puzzle together for over a year,” she says.

“You feel a little weird desecrating a hero if you find some ugly shit.”

Yuzuk isn’t done digging either. He retired from the police department in November because of a back injury from active-shooter training. He has raised just short of $4,000 from dozens of backers on Indiegogo and hopes to finish the documentary in the next few months.

But he also expects to have enough material for a sequel at some point. Even after a year and a half, there are far too many loose ends to the story. He hopes people who might have the answers to his questions will see the film and come out of the woodwork.

“The most important thing is, what was Rich doing in those last 15 years of his life?” Yuzuk says. “There are only four things it could be. One, he was completely crazy and thought he was James Bond or something. Two, he was working for a private military contractor as like an adviser. Three, he could have been working for the CIA doing some little things for them. Or four, he was doing illegal stuff on the black market, selling guns or drugs or something.”

Just before Thanksgiving, on yet another deep dive into Flaherty’s storage locker, Yuzuk found a toolbox with four audio cassettes inside. Three of them were still encased in their original plastic wrapping, but one had been recorded over. As soon as he got home, Yuzuk popped the tape into an old cassette player. At first, all he heard was the sound of a rip-roaring lawn mower.

“Fast forward, and I hear a voice,” he says. “He’s finally going to tell me the mystery of life. I listen to what he’s saying, and you can hear a phone ringing, a real weird-sounding phone. Then you hear Richard saying, ‘Hey, I’m watching Matlock.'”

The tape was just another maddening clue, but it was so typical of Flaherty that Yuzuk had to laugh.

“I’ll never know what the real truth is,” he says. “It’s like he left all these breadcrumbs for me on purpose so I can lose my life in it.”