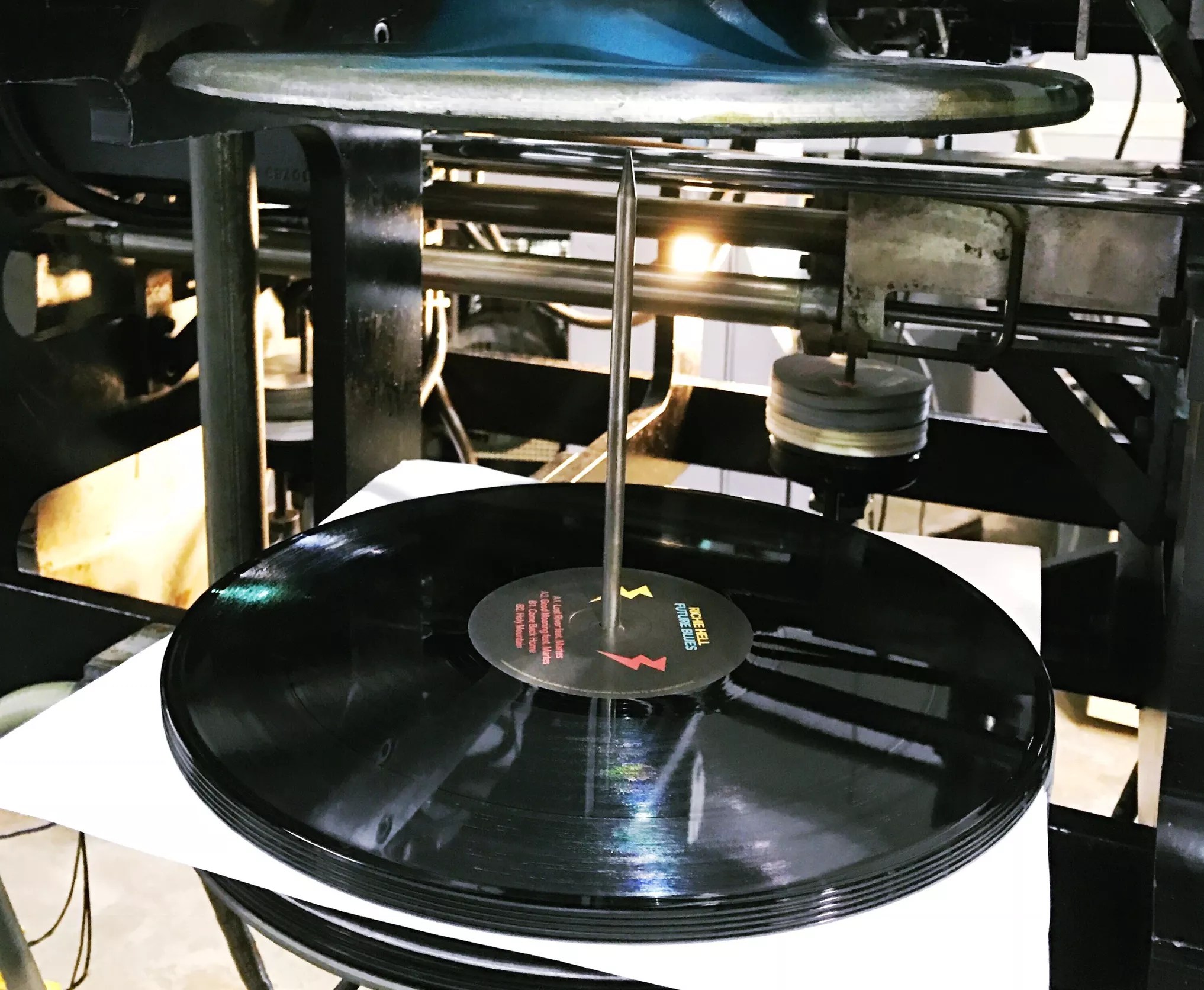

Courtesy of SunPress Vinyl

Audio By Carbonatix

Dan Yashiv remembers his first vinyl record. “I was a kid, and my parents allowed me to pick the record. It was the Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever,” he remembers, laughing. “I was like 6.”

Yashiv is a veteran music producer and president of the newly opened SunPress Vinyl, an Opa-locka record-pressing facility in the historic Final Vinyal factory, which manufactured records for the legendary Studio One reggae label, best known for producing Bob Marley’s early records.

From the dusty, potholed road steps from the entrance, SunPress looks like any other gray building on a block of warehouses. But as soon as the red painted “Final Vinyal” sign on the door comes into view, the weight of the history behind the walls overwhelms.

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

In the 1970s, reggae pioneer Joe Gibbs opened the factory that is known today as SunPress Vinyl. “Gibbs was really one of the first reggae producers,” Yashiv says. “He had an operation in Kingston, and he started sort of a satellite factory here in Miami.”

Headley Haslam came along from Jamaica with Gibbs to press the records in the plant. Haslam wears a blue old-school factory uniform and is soft-spoken, but every word he speaks is music history. His face and hands are weathered from decades of manual labor. The Final Vinyal sign inside the factory bears his name. “Haslam, Engineer,” it reads in bold black painted letters.

Haslam was there during the Gibbs era and stayed on when Studio One took over with Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd at the helm. Dodd is credited with discovering the Wailers at one of his label’s auditions in the early ’60s.

Haslam remembers pressing the records for J.C. Lodge’s “Someone Loves You, Honey” and the production boom for 2 Live Crew’s records after the group’s banned status made its music all the more popular.

When Final Vinyal shuttered in 2009, during what most thought to be the death knell for the vinyl industry, Haslam went along with it. When Yashiv tracked him down after reopening the factory as SunPress, Haslam was working in a restaurant to make ends meet. Yashiv and SunPress have afforded him the opportunity to return to the job he’s most passionate about: making records.

When the average music fan thinks about the process of “making” records, they tend to think solely of the creative process: songwriting and composition. A tour of the SunPress facilities offers a glimpse into a whole other art form involved in the record-making process: the mechanical aspect, which uses cold industrial machinery to create physical objects that play on turntables and elicit emotional responses — chills up the spine, hairs standing up, tears streaming down.

Yashiv and Haslam discuss the record-making process on a rare day when the presses are down for maintenance. They have two automatic machines online and are getting four more up and running. Their setup also includes semiautomatic machines that produce vinyl records that must be hand-cut by engineers after pressing.

After months of chasing sometimes dead-end leads on pressing equipment, Yashiv purchased the machines about two years ago from veteran vinyl engineer Chris Moss, who bought them when the plant shuttered in 2009. “I felt like Indiana Jones looking for some treasure,” Yashiv says of the lengthy hunt.

He originally thought to open the plant in Brooklyn using the machinery he had acquired from Moss but changed his mind once he learned of the Opa-locka building’s illustrious history. “It makes more sense to keep it here because the infrastructure is here,” he adds.

SunPress opened this month, and though construction is ongoing, the factory has already begun pressing records and taking orders. The company has relationships with major labels and distribution outlets, and more than half a century after “Sir Coxsone” Dodd discovered Bob Marley and pressed his records in that same building, SunPress has entered a partnership with Marley’s Tuff Gong International.

New pressings of Marley’s records are set to hit production next week on the very same machines that printed his original records. Stephen and Damian Marley too will have their vinyl records manufactured here.

SunPress is also open for business to independent artists who want to put their records out on vinyl. “This is where I come from — the indie scene,” Yashiv says. “I produced. I put out records. I want to always remember. We have relationships with all types of labels — big companies that can keep us busy, period. But our real mission is to be available for the band that can press 300 records, take it on tour, and sell it and then make another record.”

Although most vinyl-pressing plants offer artists a three- to six-month waiting period for their records, SunPress boasts an impressive six-week turnaround.

The traditionally long wait associated with vinyl record production can create cash-flow issues for bands that count on the revenue from sales to recoup the money they invest to play shows or tour. The inconvenient lag time is an ironic consequence of the vinyl resurgence. “Very few factories remain. As I investigated, it was clear that nobody has built pressing machines to [press] records in over 35 years. With the renaissance of vinyl, the demand grew, and existing factories got backlogged.”

SunPress Vinyl hopes to reach out to artists who might not be familiar with how they can put their music out on vinyl. Yashiv will host a Q&A tonight, Thursday, January 26, at Sweat Records for artists interested in learning about the process.

SunPress Q&A

7 p.m. Thursday, January 26, at Sweat Records, 5505 NE Second Ave., Miami; 786-693-9309; sweatrecordsmiami.com. Admission is free.