Warner Bros.

Audio By Carbonatix

I think I was 10 years old the first time I saw Eyes Wide Shut. I was sick in a hotel in Orlando, probably delusional from cough medicine and exhaustion while my family was out having dinner. Flipping through the channels, I ended up on either HBO or Cinemax – both of which have led many a young person into a rabbit hole of R-rated content – and stopped dead in my tracks.

There were masks. There were cloaks. There were naked women. There were no words, just ominous music and an odd sort of moan moving through it. There was Tom Cruise beneath one of the masks, and I wondered how he got there. And then there was Nicole Kidman crying in bed.

I didn’t recognize either of these people at that age – I was more prone to rewatching The Sound of Music or Star Wars around that time – but those images stuck with me. My family came back, so I shut off the TV and pretended to be asleep. I’d have nightmares about that sequence and all its haunting charm for weeks to come.

Today, on its 20th anniversary, I watch Eyes Wide Shut through a new lens – that of an exhausted, sexually active, queer man who has been in monogamous relationships. What I saw was a masquerade with elements of an orgy, the kind of cult-adjacent nonsense in which films and literature often imagine the upper echelons of society indulge. What I saw, as fascinating and unsettling as it was at the time, is now, well, kind of boring.

This isn’t meant as a slight to Stanley Kubrick; I think his film is meant to be boring. In the years since I’ve rediscovered it, rewatching it a number of times and proudly declaring it my favorite of the great director’s work, I’ve realized just how bland the fears and fantasies of protagonist Dr. Bill Hartford (Cruise) really are. In fact, I’d go as far as to say Eyes Wide Shut is the funniest movie about the limited imaginations and anxieties of heterosexual married men.

It’s riveting to watch Bill navigate this world of eroticism that’s somewhere just beyond his seemingly extensive reach. Just as in the novella that Kubrick and writer Frederic Raphael adapted for the screen, Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, or Dream Story, our doctor is experiencing a transformative journey, one that tempts him via a world outside of monogamy. His myopic worldview at the beginning is that of any well-off, seemingly happily married man: His friends appreciate him, his patients need him, his wife Alice (Kidman) loves him and only him.

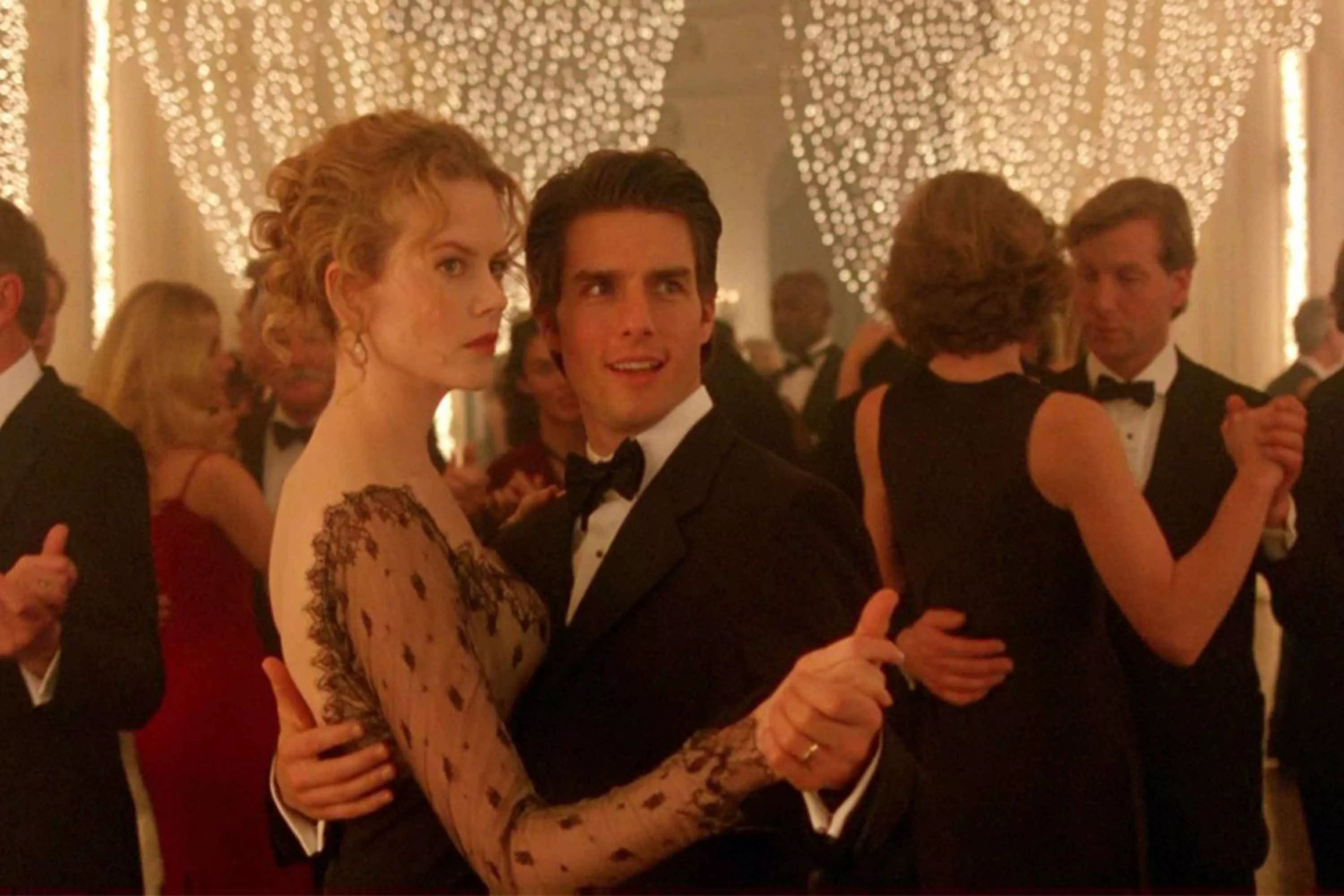

But passing flirtations at a party – an intimate dance with an interested gentleman for the coquettish Alice and the warm advances of two young models for the bashful but inviting Bill – lead to high conversations in the bedroom, becoming a battlefield of repressed desires and frustrations as they’re expressed. Everyone thinks about fucking other people, but Bill, foolish Bill, believes women are more faithful than men. He’s under the false impression that a few vows, legal documents, and a ring on a finger are enough to dispel every ounce of longing and curiosity in one’s body.

So, with Alice’s confession of fantasizing about a naval officer they once met on vacation, Bill spirals. From here on out, Kubrick does everything he can to exploit Bill’s naiveté about life and sex in the late ’90s. Cruise – with his clueless face, always expressing an itch to experience something new but terror when it doesn’t go as expected – is perfect for the role. The camera knows and exploits this: Every ounce of amusement and tension in the film is built around the fact that Bill will be exposed as the fraud he is. He doesn’t belong in this world of nightly pleasures; he belongs at home, with his wife and his daughter and the warmth of a Christmas gone right.

But as far as nightly pleasures go, Bill’s experiences are only really tangentially erotic – the bare minimum of what you’d expect a man who hasn’t done much sexually outside of his relationship would be intrigued by. The situations are appealing – nearly sleeping with a sex worker with a heart of gold, buying a costume for a voyeuristic experience, becoming aware that a party you’re crashing features public missionary sex and odd masks, playing detective to your own seemingly invented mystery – until they’re not.

The film, fascinatingly, turns all pleasure into terror. More than anything else, Kubrick is interested in showing the fear of presumed queerness that exists outside of the monotony and relative safety of marriage for a man like Bill. The fear of losing his masculinity, of losing his appeal to women, is always present. Not only does it function as the inciting incident for this journey, but it is also peppered throughout in a variety of ways, most enticing when Bill fantasizes about Alice and the naval officer. These moments of raw passion, with Kidman’s Alice shoved into a stag-film aesthetic with a seaman about to ravage her, exist not to arouse but to unsettle, puncturing the dream that is Bill’s journey.

Warner Bros.

The allure of meeting a prostitute, a kindhearted one no less, turns into the fear of death. It’s not just the death of monogamy; it’s a literal death in that she’s presumably murdered and it is revealed to Bill that she tested HIV-positive. These fears are echoed even further through his other anxieties, most notable that of being taken for a faggot. A group of men shouts the word at him and harasses him, a hotel clerk (hilariously played by Alan Cumming) flirts and fawns over a number of men including Bill, and the costume shop manager who prostitutes his daughter offers Bill a chance to indulge in the same cross-dressing pleasures as the men he met.

And while we witness a heterosexual man go through these stages of being mistaken for queer in some capacity, this perpetual fear of exposure is itself a queer fear. There’s a running theme of being exposed, physically and emotionally, that ties together with a closeted existence. And what happens when you try to explore those repressed desires? You’re warned, by the peers you thought were friends, by strangers in the night, by death itself.

Eyes Wide Shut isn’t always a subtle movie – nothing that features Chris Isaak’s “Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing” as a sort of thesis statement could be – but it doesn’t have to be. Some viewers might argue it’s uneven, unfinished, and uninteresting, and they shouldn’t be blamed. But a film so willing to explore the limitations of masculinity, the limitations of heterosexuality, and the limitations of what fantasy looks like for a man who has none, is a decidedly interesting, and queer, work with which to end one’s filmmaking career (though not by choice).

As much as Kubrick is interested in putting his protagonist through the ringer, Eyes Wide Shut isn’t without a splash of optimism. We’re all alive – characters existing in a state that’s somewhere between reality and dream, between the truth and a lie – but we won’t be that way forever. So, as Alice suggests, there’s a very important thing we need to do while we’re here: “Fuck.”

Eyes Wide Shut. Presented on 35mm with a series of short films in partnership with the 22nd Miami Jewish Film Festival. 10:30 p.m. Saturday, January 19, at Coral Gables Art Cinema, 260 Aragon Ave., Coral Gables; gablescinema.com. Tickets cost $8.