Focus Features

Audio By Carbonatix

Wes Anderson is many things: Director, screenwriter, mastermind of some of the most beloved films of the century. But he’s also a brand. His movies, filled to the brim with symmetrical shots, pastel colors, painstakingly analog production design, and snappy dialogue delivered deadpan by some of the most venerated working actors, are so stylistically recognizable that they’ve formed an entire industry. Official Criterion Collection Blu-ray box-sets, social media trends, books featuring places that merely look like they belong in his films, and other ephemera attest to the power of the Wes Anderson aesthetic: Charming, twee, handmade, and comforting, an American answer to Japan’s iyashikei (“healing”) genre or the Danish phenomenon of hygge.

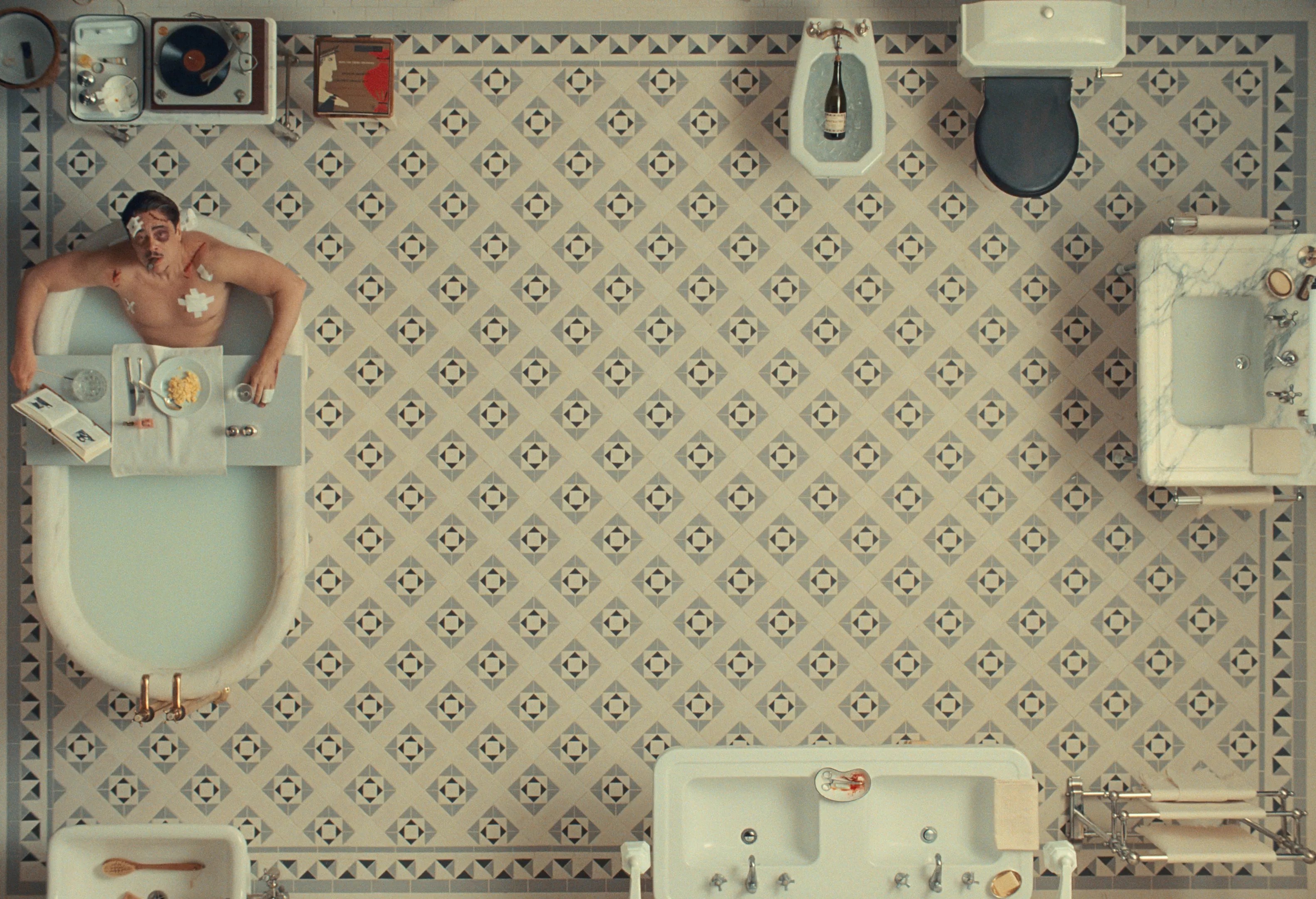

Yet it could be said that Anderson is playing against type in his latest film, The Phoenician Scheme. There is nothing twee or comforting about this spy caper’s first five minutes, which features maybe the most shocking sequence Anderson has done yet: On board a plane transporting the swashbuckling European tycoon Zsa Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro), a bomb explodes in a man’s face and annihilates the upper half of his body. When Korda improbably survives the resulting crash, he takes it as a sign that he might not be so lucky next time. He summons his daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a nun about to take her vows, who curses his villainy and hates his rotten guts, and declares her the sole heir to his fortune. He needs her help in order to execute his last and greatest deal, the “scheme” of the film’s title, an infrastructure development plan for the Near-Eastern desert nation of Phoenicia that will somehow assure his legacy.

We don’t really get a lot of insight into how the scheme works, or why it’s important, and that opacity is more or less part of the joke, initially. But as the film goes on, the novelty wears off and we start to wonder what we’re doing here. As Korda sets out with his raiding party, which, as well as Liesl, includes his seemingly oblivious Swedish entomology tutor BjÁ¸rn (Michael Cera), traveling across Phoenicia trying to negotiate with his backers to close the gap in the scheme’s funding, we start to waver in our attention. Roadblocks are thrown up, endless characters and subplots are introduced: Did Korda kill Liesl’s mother, as rumored, or was it his nefarious brother, Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch)? Will the cabal of American industrialists trying to assassinate Korda succeed? Will BjÁ¸rn’s misguided attempts to woo Liesl bear fruit?

Wes Anderson’s films are so stylistically recognizable that they’ve formed an entire industry.

Focus Features

All this results in a film that’s wildly entertaining and funny for about the first hour until we realize how coreless and tangled it is, weighed down by too much plot and too many characters. It’s disappointingly devoid of the depth and humanity we often find beneath the twee exterior of Anderson’s films. His greatest work, The Grand Budapest Hotel, deals with nothing short of the devastating sweep of 20th-century political turmoil through the lens of its titular Central European mountain resort. Here, the details enhance the characters and story, framing their struggles within a crumbling societal structure that mirrors our own, where basic decency and empathy are rapidly vanishing into thin air as the powerful mercilessly crush and disenfranchise the powerless.

Anderson tries something similar in Phoenician Scheme, presenting us with a very Trumpian figure in Korda, a ruthless plutocrat robber baron who will lie, cheat, steal, and kill to get his deals done. Like Trump, he also has an undeniable charm that often allows him to talk his way past various obstacles. Yet we’re only ever given faint indications of his villainy. We never see exactly how he makes people suffer, and the American deep-state technocrats trying to kill him seem just as crooked. Corporate espionage is rarely as interesting as spy games played by nation-states because we don’t connect to the stakes as easily.

As much as the film tries to bolster itself through Anderson’s pleasurably zippy dialogue and his always-impressive production design (the paintings are actual masterworks borrowed from the Hamburger Kunsthalle and private collections), he doesn’t give us reason enough to engage with his characters and plot beyond the surface level. As Korda goes on his own journey of self-reflection in the face of uncertain death, the resultant arc feels a bit too nice for the cynical world Anderson has constructed around him. Liesl, on the other hand, is positioned as a foil to Korda, the voice of reason and morality that will bring him to redemption. But she’s also an annoying scold whose arc is mostly about how she needs to lighten up a bit. The film is structurally less ambitious than his previous two features, to its benefit – the elaborate framing devices of The French Dispatch and Asteroid City did those films no favors. But occasionally it feels like it could have had more ambition, especially for a spy movie: Blowing a hole in a plane is one thing, but why cut away from the crash?

I’m someone who’s bought into the Wes Anderson brand. I will never miss one of his movies as long as he keeps making them. Despite this film’s flaws, I’m glad he continues to do new things with his very distinctive aesthetic. The Phoenician Scheme is yet another work by an unrivaled, utterly singular artist in international cinema, another room in the majestic palace he’s built over the past 25 years. But in this case, it’s a room I’ve spent enough time in already.

The Phoenician Scheme. Starring Benicio Del Toro, Mia Threapleton, Michael Cera, and Riz Ahmed. Written by Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola. Directed by Wes Anderson. 105 minutes. Rated PG-13. In limited release, opens locally Friday, June 7.