Photo by Osvaldo Calixto Amador

Audio By Carbonatix

This content is sponsored by Osvaldo Calixto Amador.

If you stroll through the lush, sun-dappled streets of Coral Gables, you might catch a glimpse of Osvaldo Calixto Amador- Ozzie to his friends – walking his dogs or gazing at the sky with the kind of wonder reserved for children and artists. Behind his gentle smile and easy laugh lies a journey marked by exile, loss, and the relentless pursuit of introspection through art.

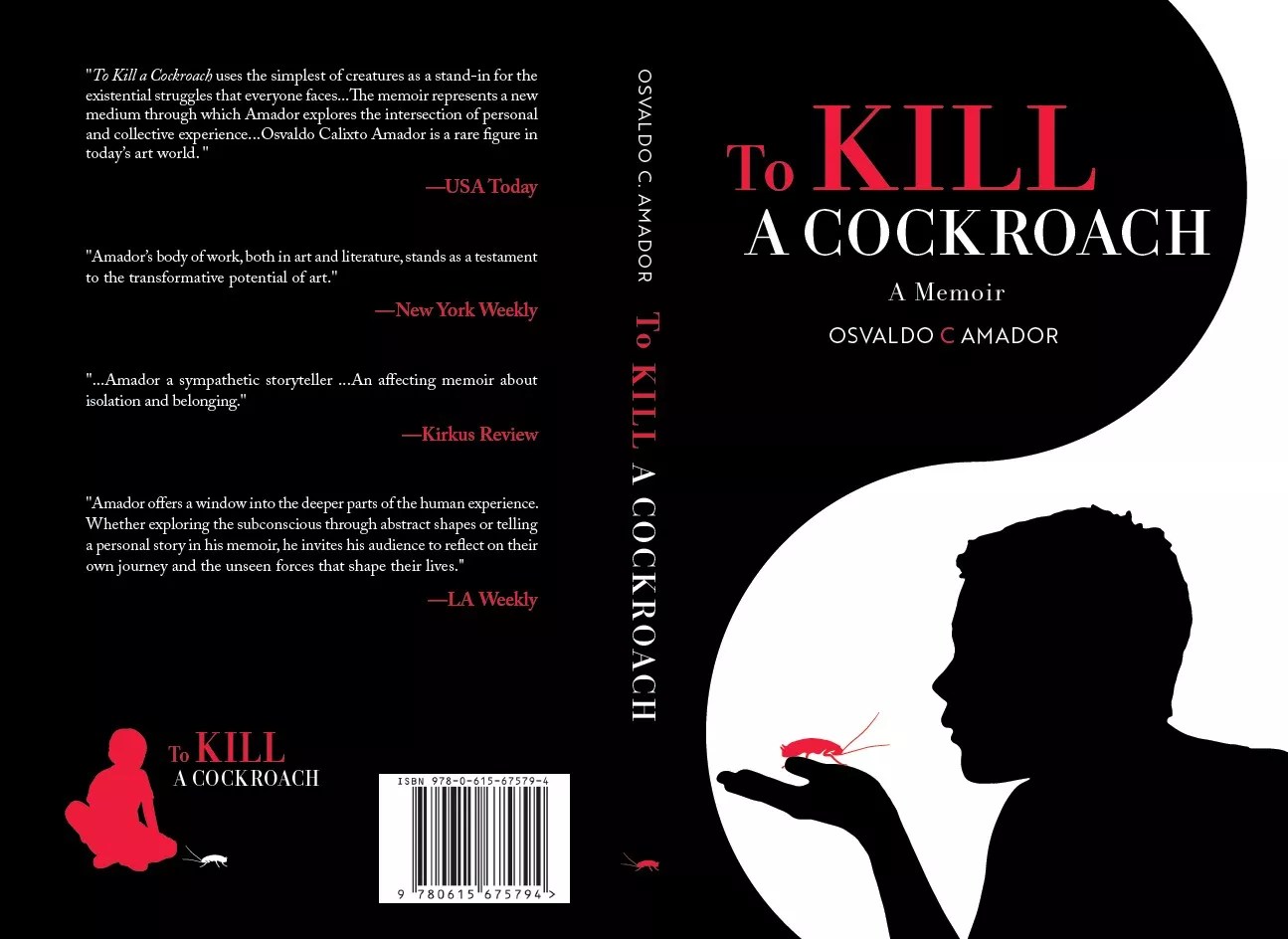

When his mother passed away, Amador lost the will to paint. Filled with despair, the Cuban-born artist put down his brush and picked up a pen. He poured his soul into a manuscript. When he was finished, he had written a powerfully moving memoir, To Kill a Cockroach, that reinvigorated his artistic drive.

The front and back covers of To Kill a Cockroach.

Photo by Osvaldo Calixto Amador

A Childhood in the Shadow of Exile

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

Born in Havana, Cuba, Amador’s life began with upheaval. He was only nine months old when left Cuba with his mother and sister. They left his father behind “because of politics.” His mother, a woman with a second-grade education, was raised in “el campo,” Cuban slang for farmlands. She carried her two children into the unknown, settling in Miami as refugees.

“She didn’t speak English, had no job, no family here. Nada. But she made it,” Amador says, pride and sorrow mingling in his voice.

The Miami of Amador’s childhood was a place of both promise and hardship. When he started school in 1970, he didn’t understand a word the teacher said. There was no ESOL. No counselors. “I was terrified,” Amador says. The solution, as his family saw it, was to move him from school to school – 18 elementary schools in all.

“I would cry. I had to teach myself how to read,” he remembers. The first book that truly captivated him was Black Beauty. “Something about that horse drew me in,” Amador says. “I was six or seven, and that book became my lifeline.”

But school was not a safe haven. “When my grandparents transferred me to a private school in Hialeah, a PE teacher molested me,” Amador says. “So now this is adding injury to pain, right? I really hated school.” By sixteen, Amador had dropped out. He didn’t know how to do multiplication tables, but he taught himself how to read.

A painting by Amador.

Photo by Osvaldo Calixto Amador

Reunion and Loss

Amador’s father remained a ghostly presence throughout his youth – a political prisoner in Cuba, subjected to torture. When Amador met his father at fifteen, after El Mariel, he remembers his dad telling him, “No matter what they did to me, they couldn’t get me to say, Viva la revolución!”

Their reunion, held at the old Miami baseball stadium, was brief but unforgettable. “It was like the most incredible moment – to feel my father’s embrace for the first time.”

His father died soon after, another loss in a life already marked by absence. “I’ve lost both my parents,” Amador says. “But people always tell me, ‘Your parents’ story is so beautiful. They’d be so proud of you.’ And I hope that’s true.”

The book is, at its core, a tribute to his parents and to the immigrant experience, but it’s also about growing up during the AIDS era. An era when Amador also lost 23 friends. “The book is mainly about how I use my art to overcome the indignities of life,” he says.

When his mother passed away in 2021, Amador found another lifeline in the written word.

“Art has always been the medium for me,” Amador says. “When my mom died, I couldn’t draw a square. I was so sad. I thought I’d never paint again. So I just sat down and wrote. I didn’t plan on publishing anything.”

Out of that darkness came To Kill a Cockroach, a memoir that Kirkus Review praised as “an impactful memoir about isolation and belonging.”

Amador’s faith, shaped by his Catholic upbringing, runs through every page and every brushstroke.

Photo by Osvaldo Calixto Amador

Faith, Philosophy, and the Power of Creation

Amador’s academic journey is as unconventional as his art. He earned a Master’s in Sociology, pursued a Ph.D. in Psychology, and delved into philosophy and religious studies. “I believe most art does not reveal everything at once; it should be discovered gradually, like the layers of the human soul,” he says.

A devoted fan of Carl Jung, Amador fills his canvases with symbols – some obvious, some hidden. “I use the cross a lot,” he says. “It reminds me of my childhood in the parish, learning about God.”

His spirituality is evident in his stained glass paintings, which often feature no human form. Amador sees art as a tool for revelation and healing.

“A painting, like life, should be savored and serve as an instrument for our inner sanctum,” he says. “Every work of art inspires us and allows us to endure the inevitable trials and tribulations of life.”

Writing the memoir didn’t just help Amador process his grief – it brought him back to painting. His works are unmistakable: bold, childlike strokes that seem to leap off the canvas. “My paintings are about that pure childlike imagination that wants to color way outside the lines,” Amador says. “I am most free and happy when standing in front of a blank canvas with only courage, faith, and imagination to proceed with the unknown.”

He credits the late professor Juan A. Martinez of Florida International University for teaching him the importance of abstraction, but the soul of his work is all his own.

“Picasso said it took him a lifetime to paint like a child,” Amador says. “I never lost that part of myself, despite the pain I experienced in my early childhood.”

Amador’s stained glass work at a church.

Photo by Osvaldo Calixto Amador

Ordinary Heroes

At the heart of To Kill a Cockroach, there is a simple yet profound message: Ordinary folks are the heroes. “Because we move on,” Amador says. “We keep living. We have hope.”

Amador’s faith, shaped by his Catholic upbringing, runs through every page and every brushstroke. “Some of my best times were when I was a kid alone in the Catholic Church,” he says. “I felt a communion with my God. We’re all heroes, just trying to do the best we can.”

Today, Amador lives in Coral Gables, surrounded by the beauty of South Florida and the animals he loves. He’s back in his studio, working on a new show – 20 paintings strong. In a city built by dreamers and sustained by survivors, Osvaldo Calixto Amador’s story is a testament to the healing power of art, faith, and the courage to begin again.