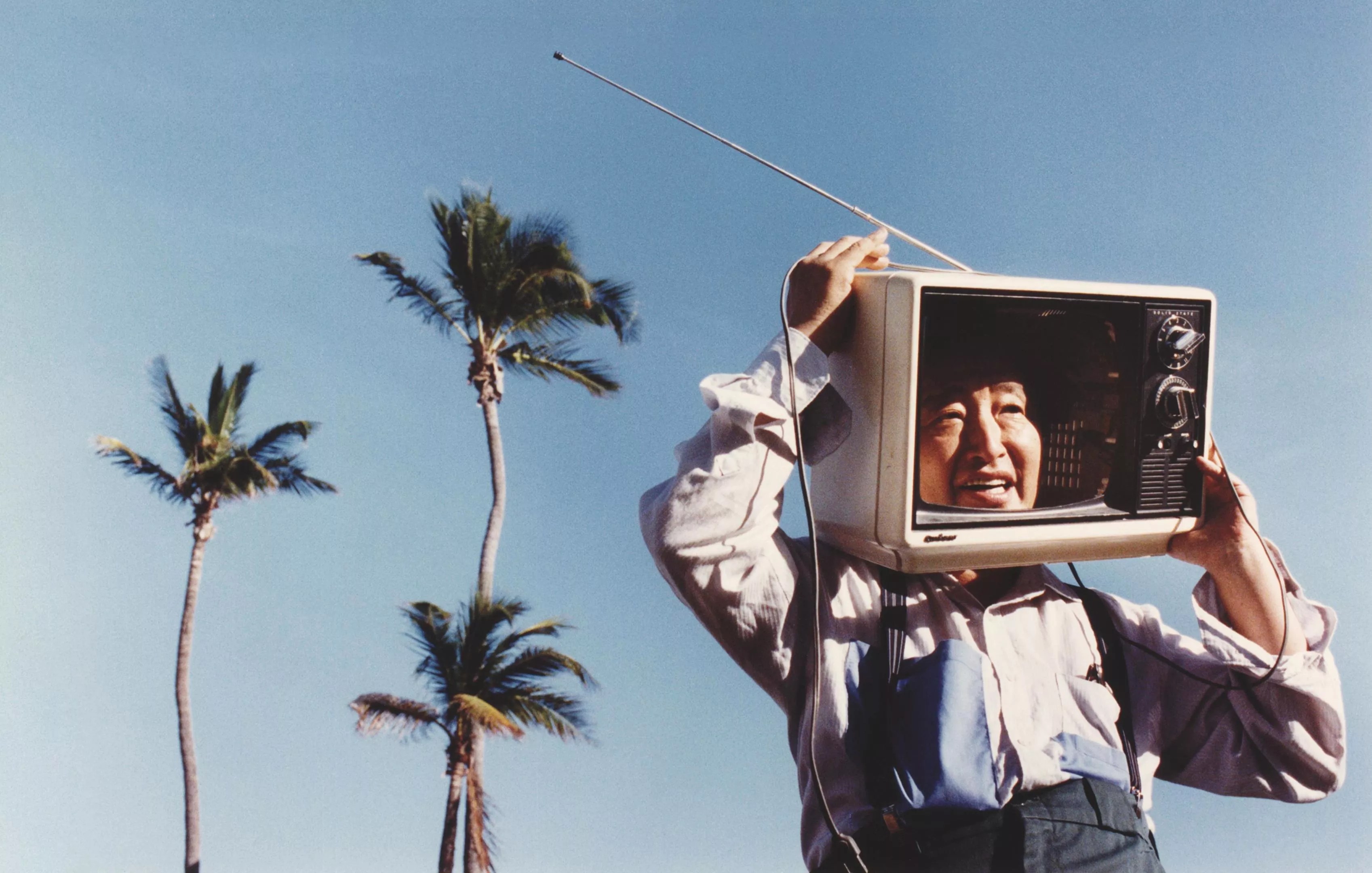

Courtesy of the artist

Audio By Carbonatix

Plenty of famous people have called Miami home, but from the late ’90s to the early 2000s, the city was home to one of the most important and celebrated artists of the 20th Century: Nam June Paik.

Usually based in New York, the globe-trotting, Korean-American artist wintered in Miami Beach, living in a beachfront condo at 1390 Ocean Drive until his death in 2006. John Hanhardt, a former curator at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and close friend of Paik, recalls how important the artist’s time in Miami was for him, especially after a 1996 stroke left him paralyzed on his left side.

“He lived in SoHo; he was an urban person,” Hanhardt says. “In Miami Beach, there was the ability to be out in this fresh air, to walk and see people enjoying the beach, and people of all types moving around and so forth. And I think that was something that he could experience and enjoy in a different way because of how physically restricted he was.”

Paik was an icon and an iconoclast, and his work opened up new possibilities for following generations of art and artists. Hanhardt calls him “a genius” and “the first really genuine global artist in terms of how he lived and worked in different places.” Although Miami became his final destination, he moved country at least three times, fleeing the Korean War to Japan via Hong Kong, then to West Germany to study music, and finally to the United States, where he set up a studio in New York in 1964. He spoke multiple languages and voraciously consumed media. Along with his affiliation with the radical Fluxus movement, he’s considered a founder of video art, a movement that used newly available consumer electronics to make stunningly new and different kinds of art.

Despite this towering reputation, Paik isn’t likely a household name in the general public. But he should be, especially in the city where he spent his final years. That’s one reason the Bass in Miami Beach is dedicating an exhibition to the artist. “Nam June Paik: The Miami Years” explores Paik’s life and presence in the city. For its opening week, the museum will host a screen of the documentary Nam June Paik: Moon Is the Oldest TV at O Cinema South Beach on Friday, October 6. Hanhardt will also visit for a talk with the Bass’ curator, James Voorhies, on Saturday, October 7, with more events planned for the new year.

“The Miami years are a bit of a blind spot,” says Voorhies, who recently became the museum’s curator earlier this year. “Because he had spent so much time down here working on projects, he also found Miami to be a kind of respite from New York and a different kind of atmosphere that was both creative and social for him.”

Nam June Paik, Bakelite Robot, 2002

Courtesy of Nam June Paik Estate

Paik and fellow video artists like his wife Shigeko Kubota and collaborator Shuya Abe didn’t simply make videos – they used TVs and cameras as sculptural materials. Some of his works are simple experiments. Often, he would place a magnet next to a TV set and see how the equipment would respond. His “TV Buddha” series features a Buddha statue staring at its image in a TV set, captured by a nearby camera, a setup that’s open to a myriad of interpretations.

Paik’s TV installations expanded drastically in scope and ambition as he gained acclaim in his later career. He designed The More, the Better, a 60-foot-tall, Babel-like tower of TV sets for South Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art to coincide with the 1988 Seoul Olympics. A 2000 commission from the Guggenheim, part of a retrospective of Paik curated by Hanhardt, featured a laser waterfall cascading down the famous Frank Lloyd Wright-designed atrium into a “pool” of TVs set up on the floor.

The creation of two of these large-scale installations initially brought Paik to Miami in the mid-’80s, and learning about them drew Voorhies to the idea of an exhibition on the artist’s time in the city. “I was curious as to where those works were and how they came about,” the curator says. The two pieces – MIAMI, featuring 74 TV monitors arranged to spell out the city’s name, and WING, in the shape of a biplane – were commissioned in 1985 by Art in Public Places executive director Cesar Trasobares and inaugurated five years later.

Sadly, the two massive, complicated installations no longer exist in their original form. “He was so far ahead of his time that those projects became challenging to maintain,” Voorhies says. “There was a lot of other construction that caused the projects to be moved, and so forth.” The installations were damaged after being moved to various locations in the airport. Some TVs broke over time, and replacements, originally sourced from a vendor in Korea, could not be found. Theft was also a problem, as Paik complained to New Times in 2001: “They stole half of my TVs.”

But while the sculptures are gone, what remains of the airport installations is their most important component, the videos that played on the TVs. The Bass worked with an archivist to restore the videos from LaserDisc, the now-obsolete format on which they were originally presented.

“Paik’s video footage was playing on the TVs in parts, and that was sourced from different media sources, filmmakers who had captured all the incredible facets of Miami and Miami Beach, the beaches and the hotels and the palm trees, and traffic scenes and so forth. He took that footage and mixed it into a kind of ‘electronic painting,’ as it’s called.” Voorhies says. “We’ve recovered the footage from the LaserDiscs, and so viewers get to see a screen playing the videos shown on those works. It’s really exciting to be able to get that from the analog LaserDiscs and into the digital format.”

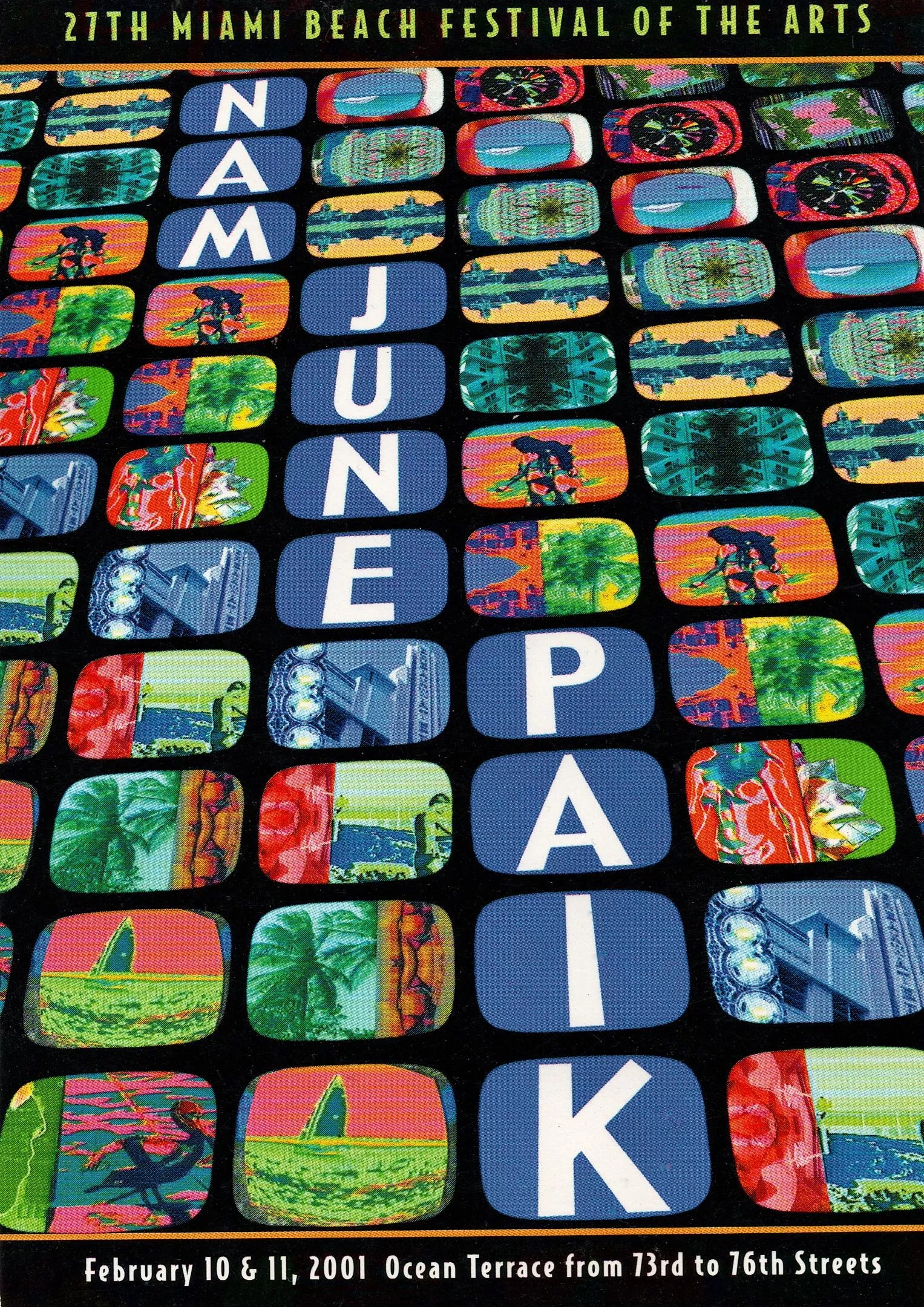

Poster and flyer for 27th Miami Beach Festival for the Arts, 2001

Courtesy of Nam June Paik Estate

The airport projects were only the tip of the iceberg for Paik’s presence in the local art scene. “Miami had what I would consider a very robust film and video scene, and Paik was often invited to present work in a number of different small or larger programs,” Voorhies says. The curator estimates that the artist had about ten public presentations in South Florida from 1982 to 2003, many at now-defunct events such as the Miami Waves Film Festival and the Florida Keys Art Expo.

“Even here at the Bass, there was a show called ‘Video Transformations’ in ’87. There was a film festival called Kino Bizarro that he participated in. So his work was also seen in a number of places during those years too,” Voorhies adds.

“He was nonstop,” Hanhardt says. “He was constantly traveling, developing new collaborations, new productions, new projects, restlessly moving from place to place, and pursuing his ideas and ideals. I mean, it was a dramatic story.”

It’s a testament to Paik’s sheer force of will that he remained relentlessly productive even after his stroke. He had begun to revisit his career, remaking pieces from his past, such as TV Cello, a 2003 version of which forms another centerpiece of “The Miami Years.” Early versions were meant to be played by Charlotte Moorman, one of Paik’s most frequent collaborators, in performance art pieces where the cellist sometimes appeared fully or partially nude. Instead of playing the new TV cello, Moorman, who died in 1991, appears on its LCD screens in videos of her past performances. Hanhardt recalls how his work changed in response to his new condition.

“He looked back through the text, if you will, to the memory of where he was then, after the stroke. How could he explore some of these issues? How could he remake pieces like TV Cello and bring a new dimension to them?” he says. “He had to create work; he had to create art. I mean, what’s what he lived and breathed.”

“Nam June Paik: The Miami Years.” On view through August 16, 2024, at the Bass, 2100 Collins Ave., Miami Beach; 305-673-7530; thebass.org. Tickets cost $8 to $15, free for members and Miami Beach residents.