"In that moment, I knew," Almeida recalls. "When I saw what song it was, I was like, 'Oh no they didn't.'"

If you grew up in a Latino household with a television, chances are this song scored your Saturday afternoon cartoons, too. It's called "The Elephant Never Forgets," and it's a playful take on Beethoven's "Turkish March" by 1970s French musician Jean-Jacques Perry. Still not ringing a bell? The title is most famously known as the unauthorized theme song to the 1970s sitcom El Chavo del Ocho and, more recently, doubles as the moniker for Almeida and Mexican artist Adrian Rivera's exhibition at Locust Projects.

"The Elephant Never Forgets" is a multimedia installation that draws from "la vecindad," the neighborhood El Chavo Del Ocho is set in, and features beloved characters like Quico and Popis, but let us set the record straight — this is no simple tribute to Latin-American children's TV. Instead, the show's lofty goal is to confront viewers with weighty questions intrinsic to their media consumption. In a world of subbing, dubbing, and remakes, what constitutes originality? Is piracy always a crime? Where does art end and soft power begin? And, hey, if it's under the guise of a trip down memory lane, then so be it.

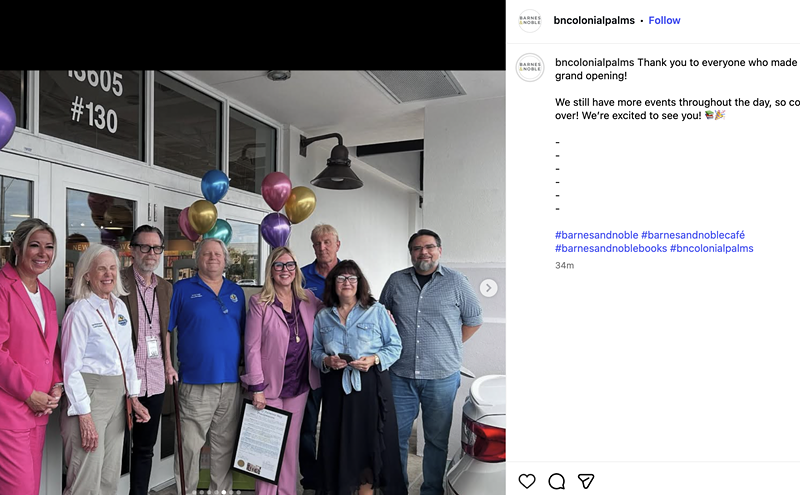

The first thing to catch your eye at "The Elephant Never Forgets" will surely be the dozens of marionettes cascading from the gallery's ceiling. Familiar faces like Jose Carioca from Disney's The Three Caballeros and Argentine comic-strip character Mafalda stare back at you while suspended on cross braces. Still, there's a gnawing feeling that something's off about these puppets. Their smoothed-out, abstracted faces reveal they are bootlegged versions of their muses and are about as real as that purse you picked up on Canal Street.

Bootleg marionettes of characters like Jose Carioca, Mafalda, and Panchito Pistoles hang from the ceiling.

Photo by World Red Eye

It's in that space between market demand and accrued sentimental value, Rivera shares, that knockoff culture in Latin America has seen immense commercial success.

Take animation, for example. Due to the high production costs of animation in the early 2000s, most cartoons were made in the U.S., Western Europe, and Japan. So what did countries like Mexico, which lacked the resources to create animated content, do? Get insanely good at dubbing. Shows like The Simpsons and Dragon Ball Z became household favorites due to their high-fidelity translations into the Mexican vernacular and their localization of humor, turning distinctly American or Japanese phrases into unmistakably Mexican ones. What was once a character that epitomized the ugly American was now a beloved Mexican cartoon personality, a recurring phenomenon in Latin American media that pushed Almeida and Rivera to explore the blurred lines of when the counterfeit becomes more authentic than the original to a culture.

The exhibition's video piece invites viewers to watch 1990s piracy ads from a leather couch.

Photo by World Red Eye

"This isn't just talking about entertainment, but also with tools," Almeida emphasizes. "My older brother was a graphic designer and to get Photoshop licensed was just too expensive. That's one aspect of how we talk about piracy as agency because these paywalls really prevent you from getting ahead. On the entertainment side, it can be more superficial, but when you're talking about tools and labor, it's something that leaves you out of the market and unable to perform."

"The main reason people buy pirated content is because it's what they can afford or what makes economic sense," Rivera adds. "You have so many countries with this massive wealth gap where it's the reality people live in versus the narrative that you're immoral or criminal by consuming these things that are just actually accessible."

Though "The Elephant Never Forgets" has been in the works since 2020, its debut at Locust Projects could not be more timely, Almeida closes. The exhibition's themes of the importance and impact of free speech and accessible media speak to the censorship prevalent in Venezuela following the country's fraudulent election results.

"I would like this exhibition to create a space for free speech and create awareness," Almeida says. "People don't have access to media in Venezuela to communicate. There's no freedom of speech, basically, and even expressing your opinion means you can be persecuted. I would like 'The Elephant Never Forgets' to be a platform to speak about what people in Venezuela cannot speak about."

"The Elephant Never Forgets." On view through November 2, at Locust Projects, 297 NE 67th St., Miami; 305-576-8570; locustprojects.org. Wednesday through Saturday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.