“I think going back that far, it’s almost as if [the Dominican government] is trying to erase this whole segment of history and population of people,” says Haitian-American novelist Edwidge Danticat. “It’s going back even before they had this huge recruitment of people to work on the sugarcane fields.”

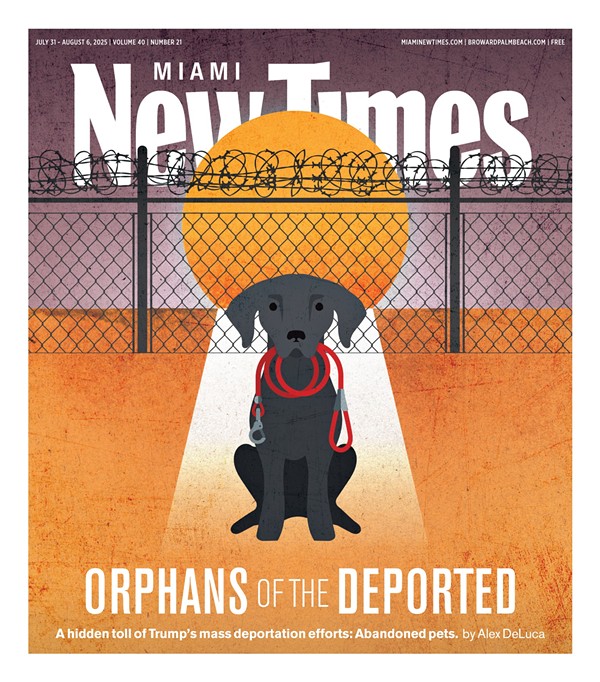

Following protests and outrage from the international community, Dominican officials passed a law allowing people to apply for legal residency with a deadline of June 17. According to Dominican authorities, only 25,000 people have received their documents, while another 40,000 have been approved, and more than 66,000 are believed to have fled to Haiti to avoid deportation.

This past summer, Danticat visited two of the informal settlement camps that have sprung up along the southern border of Haiti: one in Malpasse, and the other in Anse-à-Pitres.

“It’s a really horrible situation in which people are in the most terrible sort of limbo you can imagine,” Danticat says. “The Dominican Republic says that many of the people in the camps have voluntarily returned, but if you talk to them they say that the law has empowered their neighbors to threaten them. Others were picked up by the police and were dropped at the border. In some

Since the ruling, thousands of people have been caught between one government that wants them gone and another that is doing little to receive them.

“One of the reasons the Haitian government has given not to help [the displaced people] is that they don’t want to encourage them to settle there,” says Danticat. “The first lady has gone to visit [the camps], the prime minister has gone to visit, but they’ve done nothing for these people. We have to get past being a witness to seeing what things we can actually do — and that’s why I took my kids to see the camps.”

The xenophobia in the Dominican Republic and the conflict between the two countries goes back centuries, but many believe a crucial turning point came with El Corte, the 1937 Trujillo-mandated massacre where tens of thousands of Haitians (along with Dominicans who looked dark enough to be Haitian or could not roll the “r” in

“This situation isn’t new to me because I’ve had family members who have gone to the Dominican Republic ever since I was a kid,” says Danticat. “It’s the eternal dilemma. Governments say, ‘We want your blood and sweat for our business, for our construction, for our sugarcane, but we just don’t want you to live among us.’”

The question that remains is how to deal with the current migrant crisis, and how to prevent it from happening again in the future. Because there are elections coming up on October 25 in Haiti, it seems like the perfect time for

“The Haitian government can do more to provide more opportunities to people so they don’t have to travel en masse to places where they’re treated so deplorably and ejected at will,” Danticat says. “I think that migration should be one of the Haitian government’s main concerns, and it should be at the top of everyone’s list who is running for president so we don’t always find ourselves in these situations.”

And of course, it doesn’t only fall to Haiti and the Dominican Republic to be aware of these issues. Those of us living in the U.S., especially in Miami where there is a large Haitian population, should also take action.

“You can’t underestimate the power of information,” says Danticat. “I think our obligation as individuals should fall within the realm of our economic actions and how they reflect our responsibility to others. The way we spend our money should reflect whatever values we have and not further feed

Danticat will be appearing at the Miami Book Fair International on Saturday and Sunday, November 21 and 22. For a complete schedule, visit miamibookfair.com.

Follow Dana De Greff on Twitter.