Jerry Powers strolls the sidewalk outside the stately Biltmore Way entrance to Coral Gables City Hall. An impish 23-year-old New Jersey native with a shaggy black mop top and mutton-chop sideburns, he carries a newspaper bundle under his left arm. It is the ninth issue of the Daily Planet and Miami Free Press, a fledgling underground newspaper he founded four months earlier.

Around 10 a.m. August 25, 1969, the muggy air causes his dark polyester slacks to cling to his legs. But the stifling heat does not deter him.

Near the Mediterranean-revival building's front door, Powers hands a newspaper to a heavyset, silver-maned man, who unfolds the tabloid to reveal a front-page spoof of the City of Miami's plans to annex Coconut Grove. Powers gives copies to three other passersby.

He's daring the cops to arrest him.

Inside city hall, Coral Gables City Attorney Charles Spooner addresses a gaggle of reporters crowding his desk. The well-groomed lawyer with a Brylcreem pompadour and a tightly knotted tie says the Daily Planet is obscene and has no place in Dade County. Eight merchants who carry the twice-monthly publication have been threatened with arrest. "Perhaps we are a little bit more backcountry than a big city like San Francisco," he says. "From reading [the Daily Planet], I don't know how it meets the social needs of our community."

Powers presses on as four Gables cops approach. A tall one wearing Ray-Ban aviator sunglasses takes a copy of the Daily Planet, peruses it, and then abruptly grabs Powers's right arm. "You are under arrest for distributing obscene material," he announces while walking Powers to a squad car. The fledgling publisher sits comfortably in the back seat, his right arm hanging out the window. A reporter asks if the arrest was a surprise.

"We sort of expected this to happen because the people in Coral Gables are used to burning books," Powers declares. "The city attorney, by the way, and this is a fact and I have documentation, is on a mailing list [for] sex literature. I think [this is] his motive for causing this arrest."

"Move away," the cop barks. "No one should be talking to this man."

As the patrol car pulls away, Powers extends his index and middle fingers in a peace sign and cracks a smile.

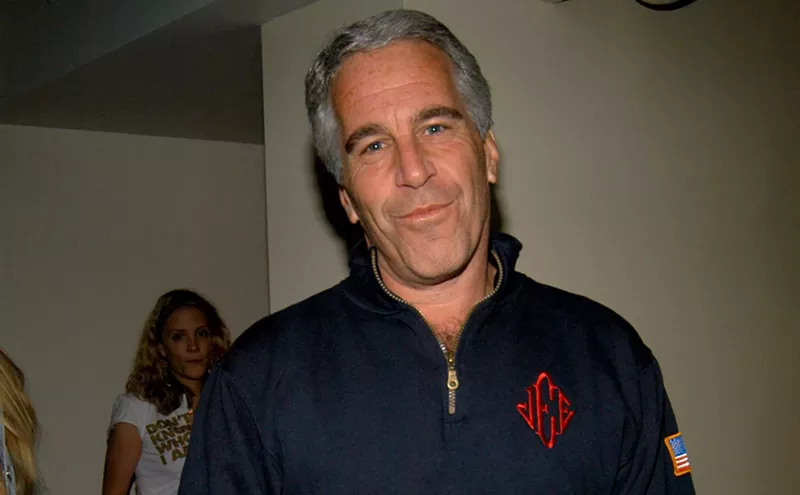

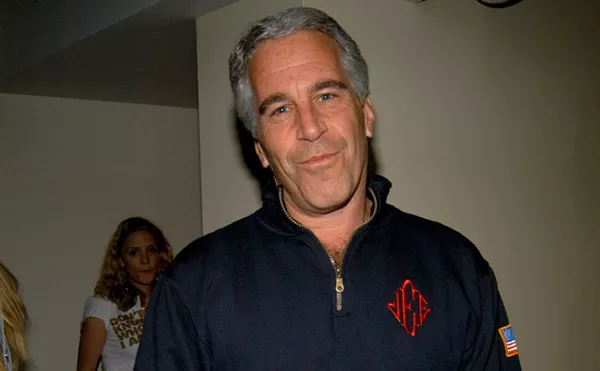

That battle against authority, caught on film, "was among the first of many arrests" Powers recalls during a recent conversation inside his $1.4 million Sunset Island estate with a gun-metal gray Aston Martin convertible parked in the driveway. "There was also a time when the cops used a battering ram to get into my house because they thought I was dead from an overdose."

Today the long black locks and heavy sideburns are gone. Sitting on a cream-colored sofa in his wood-floored Florida room, the 63-year-old recalls a life spent narrowly avoiding disaster. Born just months after his parents emerged from Nazi prison camps, he escaped the fury of racist bullies in the '50s and survived angry mobs in the '60s. He also beat felony charges for writing bad checks and avoided prison time for not reporting his taxes in a timely manner.

"I was definitely part of that culture that did a lot of drugs," Powers reflects. "And you do a lot of stupid things when you are on drugs. I was lucky to get out of that mess."

He hasn't done drugs in years, but he's still getting into trouble. After 15 years as publisher of one of America's best-known glossy magazines, Ocean Drive, Powers was recently pushed out by the new owner, Niche Media. Now he's at war with his former partners. On one front, he has sued Niche in federal court for illegally trying to silence him. And in Miami-Dade Circuit Court, the widow of former Ocean Drive investor Derick Daniels has accused Powers of swindling her out of millions of dollars.

It's all in a day's work for the man who, more than anyone else, molded Miami Beach's glamorous lifestyle.

----------

Frigid air stung Blanche Sandler as she slogged through snow-blanketed Bydgoszcz, a small town in northern Poland. The Red Army only hours before had liberated her from the Bromberg-Ost women's concentration camp. The emaciated but still pretty 16-year-old weighed less than 100 pounds. By the time she was freed January 16, 1945, she had lost her entire family.

Three days later, while on the way to a village doctor, she bumped into a 22-year-old refugee named Henry Pulwer, who had also narrowly escaped the Nazi death chambers. "He had a wonderfully handsome, long face," she says in a thick Yiddish accent muffled by soft sobs. "He escorted me to my doctor, and we just grew close from that moment on."

Henry and Blanche (who dislikes sharing memories of the numbers tattooed onto her arm or life in the camps) soon married and relocated to Tirschenreuth, Germany. On June 9, 1946, she gave birth to their only son, Jerry Michael Pulwer. "He was the first baby born in that town after the war," 79-year-old Blanche attests. "He was a gorgeous boy."

He keeps a photo that shows him at age 3, smiling and holding his parents' hands. His black hair is parted neatly to the right, and he's dressed in lederhosen. He has his mother's cleft chin, round face, and thick eyebrows.

Three years later, the small family immigrated to Paterson, New Jersey. "The first year was very hard for us," Blanche continues. "I was working in a sewing factory for 65 cents an hour. My husband also worked in the factory."

The family lived on the fourth floor of a brownstone apartment building for about a year and a half. "I remember little Jerry wanted a bicycle," she recalls. "I didn't get it for him because we didn't have an elevator."

Those early years helped shape the ethos that would drive Powers to South Beach and succeed-at-all-costs fame. "I only spoke German," he says. "And back then, kids calling you an immigrant wasn't a pretty thing. I remember several times walking home and getting the shit kicked out of me."

In 1954, Blanche and Henry (who died in 2005) used money paid to Holocaust survivors to buy a two-bedroom house in Fair Lawn, about a half-hour from Manhattan, and opened a diner-style restaurant in nearby Passaic. "I finally got him the bike he wanted," Blanche recalls. Five years later, she gave birth to Jerry's only sibling, his sister Roz.

At first, Jerry didn't have many friends, but during adolescence, things changed. "I'd go over to people's houses, play pick-up basketball games in driveways, go to dances," he says. "My mother had one rule: I couldn't go out until after Shabbat dinner on Friday night."

His entrepreneurial ways emerged during these years. He made money DJing at local parties and dances in church basements. "I picked up $70, $80 on the weekends," he remembers fondly. "I saved up enough money to buy two turntables, an amp, and a reel-to-reel recorder, the closest thing you could get to an iPod Shuffle in those days."

When he turned 18 in 1964, Jerry graduated from Fair Lawn High School. He took a job as a DJ for a New York radio station, working the weekend graveyard shift. A friend suggested he change his last name. "I settled on Powers," he says, "and legally changed it in the '70s."

He had another passion: writing. He enrolled at Fairleigh Dickinson University, but quit two years later to take a job as a copy boy at the Paterson Record. His duties included contacting relatives of soldiers killed in the Vietnam War and obtaining photographs of the dead men. And, he says, "I was on a team of ten reporters covering the arrest of boxer Rubin 'Hurricane' Carter, who had been charged with a triple murder."

Soon Powers was promoted to general assignment reporter, and in July 1967, he covered race riots in Newark and Paterson. "I was with a New York Daily News reporter when we started getting shit thrown at us," he says. "We both crammed into a phone booth and called WPIX... We were live on the radio, reporting what was happening, and the cops came back and got us out."

About a month later, he visited Miami. "I fell in love with the place," he says. So he quit his job, loaded up his stuff, and moved into a one-bedroom apartment on Tigertail Avenue in Coconut Grove, then Miami's hippie central.

"I participated in love-ins and peace rallies at Greynolds and Peacock parks," he remembers. "I smoked a lot of pot and did a lot of acid, peyote, and mushrooms."

He landed a gig as a DJ at a station called the Magic Bus, today's Love 94. It was headquartered on First Street in Miami Beach, where he would get his first taste of the turf he would come to dominate. "I played rock music, and I had some celebrity guests come on like Tommy Smothers and Bill Cosby," he notes.

Soon he wanted to return to print journalism. "I didn't see myself writing for the Miami Herald," he says. "I wanted my freedom, so I started my own newspaper."

So in April 1969, Powers launched the Daily Planet and Miami Free Press, a tabloid he labeled "the Bible of Sadomasochism." The first issue's cover included a sketch of a naked woman with her legs spread. The second one featured an illustration of a marijuana cigarette with the headline "What Miami Needs Now Is a Good 5 Cent Joint."

A crew of free-thinking writers, editors, and photographers produced essays about pop music and social commentary with four-letter words. It was anti-war, anti-police, anti-establishment. "Half the time, I didn't have money to pay the staff," Powers laments.

Mark Diamond was a 15-year-old kid when Powers hired him to shoot photos for the Daily Planet. "I didn't make any money," Diamond says. "But through the Daily Planet, I shot photos of Allen Ginsberg, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and all these cool people... Through the paper, I was also able to get freelance work with Rolling Stone. It was a bitchin' time."

On August 30, 1969, six days after the arrest in Coral Gables, a judge convicted Powers of distributing obscene literature and sentenced him to 60 days in jail, but he served only one day after winning an appeal. However, the ruling applied only to the August issue of the Daily Planet. Powers continued to distribute and sell his underground newspaper for another five years.

Henry Stone, who produced gold and platinum records with KC and the Sunshine Band, was a regular advertiser. "I really liked Jerry's attitude," Stone says. "We hit it off and hung out at the clubs together. Miami was a swinging town back then. And Jerry was a very progressive guy."

----------

In the early 1970s, the Magic City was a heady place. Then part publicist, part newspaper owner, Powers was a force to be reckoned with in the city's counterculture. One of the people he stewarded around town was Allen Ginsberg, the famous poet who was the voice of both the beatniks and the hippies. "I brought Ginsberg to Miami Marine Stadium for a poetry reading," Powers recalls. "He read his famous poem, 'Howl,' but he changed one line to say, 'The police in Moscow are like the police in Miami.' The cops providing security just went apeshit and shut us down."

A few years before, at a drive-in on the John F. Kennedy Causeway, Powers met a petite 20-year-old brunette, Sandi, who would become his wife. Together they saw Hair at the Coconut Grove Playhouse from the front row while tripping on acid, and accompanied Doors lead singer Jim Morrison to an intimate performance of Canned Heat at the Newport Hotel in Sunny Isles Beach. Morrison had been busted for indecent exposure March 1, 1969, and thrown in jail. "It was when he had to come back to Miami for his court date on the obscenity charge," Sandi says. "He got up onstage, but the owner asked us to take him out of there. He was afraid he was gonna pull another stunt."

Hanging out with the most popular artists of the era prepared Powers for his turn with the famous and the fabulous in South Beach near the end of the 20th Century.

In 1972, Miami Beach hosted both the Republican and Democratic presidential conventions. That year, Warner Books hired Powers as a publicist for Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, leaders of the yippies, who held massive protests here. The young newspaper publisher was tasked with contacting radio stations and newspapers at the end of each day to report on the duo's doings. "The police planted an undercover agent in our office," Jerry cracks. "His name was Paul Hammond. If that was his true identity, I don't know. We had fun with him, though. We dropped LSD in his soup. He was so stoned out of his mind he didn't remember who he worked for."

There is, of course, no way to prove the truth of his story.

As the hippie love era came to a resounding end, so did Powers's success. In 1971, he was arrested once for writing bad checks. Some were small ($15 to a Missy Alspach), and others were large ($1,278 to Always Better Service Plumbing). He fought some of the charges, and in several cases, warrants were issued for his arrest after he didn't show up in court.

In 1972, his daughter Jacquelynn was born, but that didn't change his lifestyle. The next year, police busted him for public drunkenness and possession of cocaine. (The charges were later dismissed.) And in 1978, he was nabbed for trying to obtain drugs with a forged prescription. That felony charge was reduced to a misdemeanor and transferred to county court, where, Powers recalls, he was found not guilty. (The records have been destroyed.)

Civil court records show Powers was sued 13 times between 1977 and 1984 for money owed. "I was dependent on drugs when I did those things," he says. "I was stoned and broke. There is no question I wrote checks even though I didn't have money to cover them."

His drug diet consisted of cocaine, barbiturates, amphetamines, "and whatever else was around," Power says. In 1984, he claims, he went cold turkey. By then, he, Sandi, and their then-12-year-old daughter had relocated to Manhattan.

After a brief career as a book agent, Powers in 1986 signed on as business manager for pop artist Peter Max, whom he'd met years before. Both men reaped the fruits of the '80s art boom. Powers purchased an apartment on Manhattan's Park Avenue and bought a summer house in the Hamptons. Max, whose psychedelic work includes the Beatles' Yellow Submarine image, became an international superstar.

The pair's lavish spending caught the attention of the Internal Revenue Service, which audited Powers and Max in 1990. IRS investigators discovered Powers had not reported more than a half-million dollars in income earned selling art in 1988 and 1989. According to federal documents, Max also failed to report $1.1 million in sales.

By early 1992, with the IRS breathing down his neck, Powers severed his relationship with Max and sought a new venture in a much warmer and friendlier clime. His buddy Henry Stone remembers meeting Powers for dinner one evening in Manhattan. "He announced he was coming back to Miami," Stone says. "He had this vision about doing a magazine."

Powers claims he and his wife came up with the name during a New Year's Eve stroll on Ocean Drive one year earlier. "When the clock struck midnight, Ocean Drive was just a lively place," Powers says. "The atmosphere just captured the concept we were going for."

----------

In November 1992, Powers was in South Beach, ready to launch the new monthly magazine chronicling the social, fashion, and modeling scene that was burgeoning. He had a new business partner, Jason Binn, the 24-year-old son of Manhattan millionaire Moreton Binn. The younger Binn had been a top sales and marketing executive for Michael Warren, a New York-based garment maker. He declined to be interviewed for this story.

The magazine's first editor-in-chief, Lori Capullo, remembers starting out in an office above News Café on Ocean Drive at Eighth Street. She spent a great deal of time trying to land an interview with famed fashion designer Gianni Versace, who was staying at the Marlin Hotel in Miami Beach. "Jason and Jerry really wanted to get Versace because we were using a photo of supermodel Claudia Schiffer in one of his evening gowns for the cover," Capullo explains. "But we kept getting the runaround from his publicist. We found out where he was and Jason sent him a bouquet of flowers."

Within two days, Capullo says, Versace contacted her through the hotel's concierge and agreed to an interview. "At the end of our meeting, Jason and Jerry came over," she says, "and they did the whole pose-with-a-celebrity photo."

Powers says they lucked out with Versace. "He had fallen in love with Miami Beach," he explains. "He wanted to be part of the community. We caught him at the right moment."

To compete with national magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair, Powers decided to focus on the stars. "Ocean Drive was always meant to be a money-making operation that was all about celebrities, fashion, and Miami," Powers says. "We weren't going to be the Miami Herald or the New Times."

So when the inaugural issue came out in January 1993, the magazine did not disappoint. Schiffer graced the cover, and the Versace interview was the main story.

Club promoter Michael Capponi, at the time a teenage surfer kid from Miami Beach, remembers handing out copies to pretty girls on the street. "People were just blown away," Capponi says. "Here was this bright-colored magazine with photos and stories about the locals who were making Miami Beach a cool place to be."

Indeed, the timing couldn't have been better. After years of being stereotyped as a city of elderly retirees, South Beach was again becoming cool — as it had been in the '50s and early '60s — both in the northeastern United States and Europe. Ocean Drive would cement that image. Soon advertisers were clamoring for space.

Yet amid all the good fortune, Powers still had to deal with a serious problem in New York. The same month Ocean Drive made its splashy debut, the U.S. Attorney's Office in New York indicted Powers for not reporting the $560,000 he made in 1988 and 1989. On January 20, 1993, Powers pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of failing to file a tax return in a timely manner. To avoid prison time, he helped the government nail his former client, Max, who in 1996 was charged with 11 counts of conspiracy and tax fraud. In response, the artist claimed Powers had shown him how to cheat Uncle Sam.

On June 22, 1998, Max pleaded guilty to two counts of tax evasion. He received two months in prison and two years of supervised release. Less than a month later, Powers was sentenced to three years' probation.

During the half-decade of court hearings, Powers distracted himself with Ocean Drive. From the beginning, their plan called for circulating about 40,000 copies. Local distributors could commit to accepting only 2,000 copies at a time, so there was no way Binn and Powers were going to make the magazine profitable by selling it on newsstands. "And they told me they would do their best to sell only 20, 30 percent of those," Powers says. "I needed to get the magazine out to everybody in order to make an impact."

Feature stories about developers such as Tony Goldman and Craig Robins and restaurateurs such as Mark Soyka, along with gossipy articles covering South Beach nightlife and fashion, filled the magazine. But it was the photos — beautiful women dressed in haute couture — that defined the glossy as the standard bearer of all things fabulous in the Magic City.

Start-up costs nearly doomed the magazine. A company now called St. Ives Press sued Powers for refusing to pay $18,500 in printing fees for the debut issue, and eventually he agreed to fork over $14,500. After the first year in business, Ocean Drive needed another $350,000 to become self-sustaining. "It was a cash-crunch problem," he insists, "based on our success."

So Powers and Binn brought in investors, including South Beach real estate magnate and playboy Thomas Kramer, whose womanizing and partying became a regular feature in Ocean Drive. Though Kramer's role as both story subject and owner seemed to blur the line between advertising and editorial, Powers is unapologetic. "This was a guy we would have written about whether he had invested or not because he was a Miami Beach character," he says. "And we never had a separation of church and state between the editorial and advertising side."

Powers also received $50,000 from Binn's ex-employer, Warren, and $100,000 from Derick Daniels, a former president of Playboy Enterprises. Daniels was paid $4,166 a month as Ocean Drive's editorial director for most of the magazine's existence.

Circulation was upped to 50,000, and they were off. From early on — in the manner of Vanity Fair — the magazine threw anniversary parties that became the most coveted invite in Miami. Hip-hop mogul Sean Combs, Hollywood director Michael Bay, New York Yankees shortstop Alex Rodriguez, former heavyweight boxing champ Lennox Lewis, actor Michael Douglas, supermodel Elaine Irwin, and NBA superstar Shaquille O'Neal are just some of the celebs who have walked the red carpet during the 16 years of Ocean Drive fetes. The next one is planned for this winter.

The partnership of Powers and Binn drove the magazine. Binn was "running around selling ads" while Powers "managed the business," Capullo says. They were gregarious, and popular — the public faces. Together they would hit the scene. "We'd go to all the cool restaurants and clubs like the Living Room, the Strand, Bar None," Powers says. "We'd see clients together. He'd come over to my house and go for a swim. Those were good days."

Powers brags that the success of the magazine allowed him to buy out Kramer in 1998 for "$2.7 million, more than ten times his investment."

Over the next few years, Powers expanded his empire by publishing Palm Beach magazine and Ocean Drive en Español, a partnership with Emilio and Gloria Estefan. He also launched titles called Atlanta Peach, Inside Out, and Trump. In 2003, Ocean Drive partnered with Greenspun Media Group — a Henderson, Nevada-based company that owns 30 publications — to launch Vegas magazine.

Binn began to branch out on his own, launching titles in the Hamptons, Manhattan, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. This separation would turn out to be significant in a later split between the two.

Every one of the magazine titles controlled by Binn and Powers followed Ocean Drive's formula of catering to the affluent; if you didn't fall into that category, you'd better be damn beautiful. At a time when traditional print media enterprises such as daily newspapers were trimming staff and shuttering news bureaus, Ocean Drive Media Group and Niche Media were thriving. The simple formula: glorify celebrities and local luminaries.

It worked beautifully. Powers says Ocean Drive Media Group made a profit of $500,000 in 1999. The following year, that doubled to $1.1 million, and by 2004 and 2005, the magazine made close to $10 million. Those figures are pretty much confirmed by later public sales data.

"They made controlled circulation sexy," explains Samir Husni — a publishing industry analyst and journalism professor at the University of Mississippi — referring to the bulk of Ocean Drive's targeted free distribution.

"Controlled circulation in the good old days was for a specific audience," Husni says. "If you were a black chemical engineer, then you would get a copy of Black Chemical Engineer Monthly in the mail. What Ocean Drive does is target those individuals who consider themselves the cream of the crop, and not only get them to see the magazine, but also see themselves in the magazine. And that is what makes Ocean Drive attractive to advertisers."

The success of both companies wasn't lost on Michael Carr, then-president of Greenspun Media. In early 2007, he approached Powers and Binn about buying their companies and consolidating the magazines under the Niche Media name.

Carr and Greenspun bought both Niche Media and Ocean Drive Media Group (ODMG) November 1, 2007. The overall cost of the deal has not been disclosed, but just the ODMG part was valued at $30 million, according to recent court disclosures. In addition, Powers was named president of Niche Media's publishing division, with a $725,000 annual salary plus benefits averaging $300,000 a year. As part of the deal, he signed a noncompete agreement that would come back to haunt him.

"Niche has a group of publications that could end up being the most dominant ones in the marketplace," says Carr, who left Greenspun this past July. "These are challenging times, but the opportunity still exists to do that."

Last December, Niche Media laid off more than half of ODMG's workforce, including longtime editor Glenn Albin and creative director Carlos Suarez. The company also shuttered Ocean Drive en Español, Atlanta Peach, Inside Out, and Trump.

One Greenspun insider who asked not to be named says the only profitable magazine was Ocean Drive. "All of Jerry's titles were closed except the flagship," the insider states. "What company would close a magazine if it were a success? Ocean Drive survived because it is a huge brand."

----------

Powers walked into the Ocean Drive offices at 404 Washington Ave. feeling sad the morning of this past February 17. "No one knew it was my last day," he says. "We called an impromptu staff meeting, and I told everyone I was taking a break. I urged them to maintain the quality of the magazine and to continue to be proud of it."

He shed a few tears before returning to his desk. With the help of his secretary, he packed up his belongings, including plaques, awards, pictures, and copies of early issues. He stared at the first cover with Claudia Schiffer for a good minute. "I put my entire 15-year history with the magazine into boxes," he says. "It was really emotional, but it didn't hit me that I wasn't going to be a part of Ocean Drive until a few weeks later."

The day Niche forced Powers to resign, Ocean Drive's February issue featured Food Network celeb Padma Lakshmi on the cover. It was a 218-page book that included longtime sections such as "Beach Patrol," which spotlights a local entrepreneur, and "Shot on Site," pages and pages of photos depicting local, plugged-in, beautiful people at swanky events around Miami. In fact, it's difficult to see a difference in the magazine's content and production quality before and after the Powers era.

The ex-publisher says he was ready to retire. "I thought I wanted to live the last quarter of my life on a hammock between two palm trees," he explains. "I thought I would be happy traveling, snorkeling, and boating in the Caribbean."

He and his wife Sandi went on a three-week vacation to Saint Barts. Powers says he was beside himself after the second week. When he returned home, he opened Power Play Studio, a photography and video production center in midtown Miami. Soon, though, he realized the recession had all but killed his market. "The economy here has not come back," Powers says matter-of-factly. "And the fashion photography business has moved on to other exotic locales."

This past May, retired Miami Heat star Alonzo Mourning invited Powers to mentor 19 teenagers at the Overtown Youth Center, a public facility that caters to inner-city kids, to produce a not-for-profit magazine called IE2: Inspire, Enrich & Empower. Mourning is the center's chairman emeritus. Powers spent June, July, and August teaching the youngsters. He recruited some of his old employees to help the kids. The one and only issue was supposed to come out in September. The kids sold 25 ads for a total of $10,000 to pay for printing. Any remaining funds would be donated to the youth center. Some of the advertisers included companies that buy ad space from Niche Media.

Apparently that didn't sit well with Binn and his Greenspun bosses. According to a federal lawsuit Powers filed against Niche Media last month, Binn told the youth center chairman that Powers's involvement in the magazine violated the noncompete agreement. Legal action was threatened.

Powers filed his lawsuit as a preemptive strike for two reasons, he says. First, Powers claims, he wants the youth center teens' magazine published. Second, he is determined to return to magazine publishing. "I've read my noncompete agreement," he says. "It clearly states that I can go back to work two years from the day I sold Ocean Drive, which falls on November 1 of this year."

In its counterclaim, Niche Media accuses Powers of using the youth magazine as a publicity stunt.

But even if Powers wins that fight, he still must contend with the widow of another former magazine investor. Lee Daniels, whose husband Derick helped mold Ocean Drive during its early days, sued Powers, his wife, and his daughter in Miami-Dade Circuit Court in February 2008. According to the complaint, which is still pending, Powers cheated Daniels out of $2 million from the sale. According to a November 1992 agreement that her husband (who died in 2005) and Powers signed, the Danielses owned 10 percent of the company.

Lee Daniels accuses Powers of driving down his firm's value by $18 million so his partners would get a lesser share. She also claims that in 2007, Powers diverted $2.7 million in magazine revenues to support his lavish lifestyle, including paying for the upkeep of his vacation home in Saint Barts and a yacht docked on Fisher Island.

Powers will say only that the lawsuit's claims are "totally false." Lounging inside Power Play Studio, he prefers to talk about his future. "I am far from being retired. I'm ready to start my next media adventure, which is only limited by imagination. I want to be surrounded by creative people making magic."