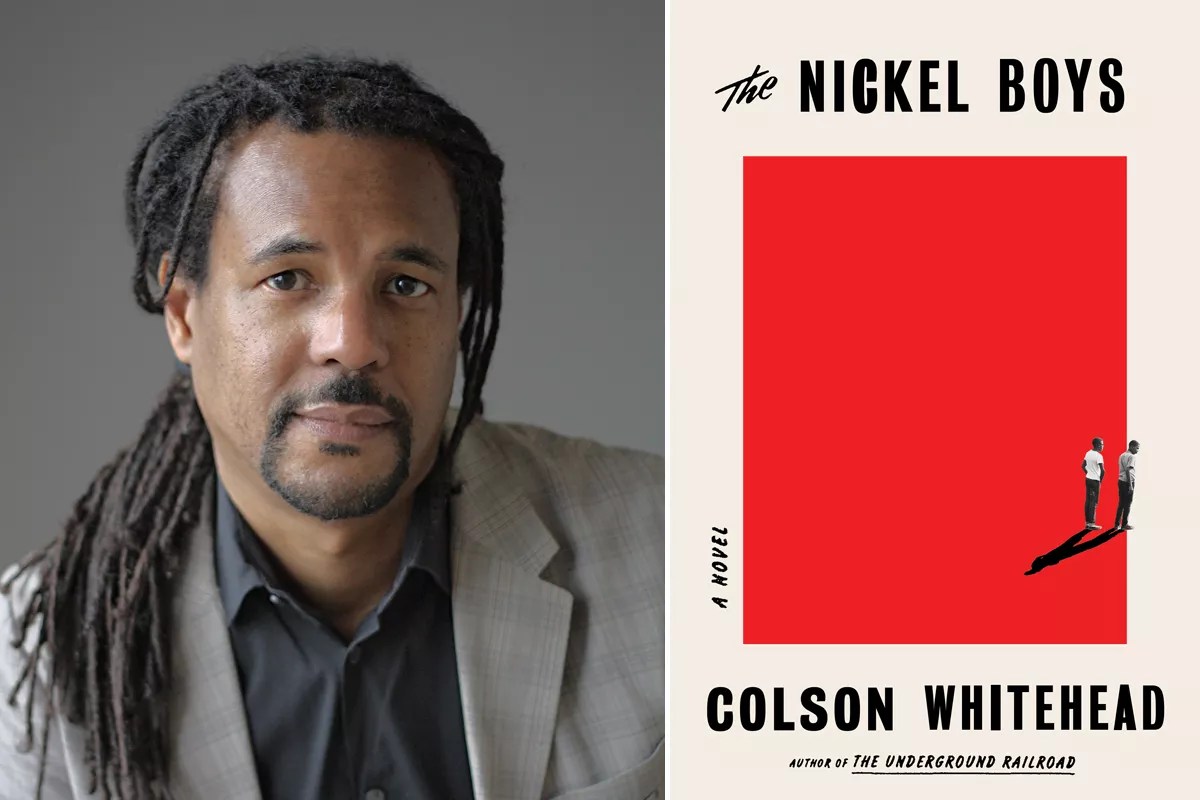

Artist management / Doubleday

Audio By Carbonatix

Elwood Curtis watches the news coming out of Florida from his adopted home of New York City. As articles in Tampa Bay, Miami, and even international newspapers are reporting that dozens of skeletons are being unearthed on the grounds of a boys’ ostensible “reform” school, Curtis remembers. He is one of the “Nickel Boys,” those who survived inhumane conditions and continued their route to an adulthood haunted by harrowing memories.

Curtis is the main character in The Nickel Boys, MacArthur Fellow Colson Whitehead’s followup to his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Underground Railroad. The new book is a fictionalized account of the infamous Dozier School, which has continued to make headlines as ersatz graveyards are discovered on the closed reformatory’s grounds. And though the idea of reading a novel that chronicles the degradations inflicted on the children incarcerated at the Nickel Academy might seem difficult, Whitehead has filled his novel’s pages with the humanity of Elwood Curtis and makes readers eager to see him survive. Most of the book is set outside of the Nickel Academy, though Elwood struggles to erase its stain from his soul until he is an old man.

Readers meet Elwood in the 1960s, around the time Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in St. Augustine for attempting to integrate that city’s businesses. (For remarkable footage of King’s arrest, see this AP film.) Having educated himself on civil rights in secret, in order not to upset his grandmother or his employer Mr. Marconi, Elwood chooses his moment to make a stand. But when he marches against the local theater’s segregation policies, he is shocked to see his teacher and other students there.

“He’d kept his movement dreams so close that it never occurred to him that others in his school shared his need to stand up,” Whitehead writes.

A lesser writer’s desire to represent the mostly white guards at Nickel as evil incarnate and their charges cherubic in order to drive home the point of the school’s inhumanity would have made for terrible prose. Instead, Whitehead demonstrates how a combination of white supremacy and macho peer pressure predicated on the notion that the toughest guards were the most manly created monsters of average men. He also shows how even with the keenest desire to be a model inmate, luck – or fate – was the real determinant of how each boy was perceived by guards. Even in a world of brutal black-and-white views of crime and punishment, Whitehead’s writing forces readers to deal with the ordinariness of most of the characters.

Elwood’s impulse to protect a weaker boy results in his first beating: “The white boys bruised differently than the black boys and called it the Ice Cream Factory because you came out with bruises of every color. The black boys called it the White House because that was its official name and it fit and didn’t need to be embellished.” What happens there leaves Elwood with physical scars, but his understanding of his vulnerability will follow him for the rest of his life.

Afterward, when his grandmother comes to visit, readers might find themselves urging Elwood to tell her the truth about what happens at Nickel. But Elwood has already ascertained that any truth he tells her will be covered over with school officials’ lies, followed by Elwood’s own disappearance. During the years that the real Dozier School operated, each time the school’s execrable conditions were publicly exposed, reform was promised – but no matter the supposed reforms, the conditions reverted to status quo ante almost immediately. As reporters at the Tampa Bay Times wrote, complaints were lodged against the school beginning in 1903, the first of many criticisms paid scant attention by those who considered the boys – some of whom were as young as 5 years old – hopeless causes.

Elwood also understands that every time a person wishes prison rape on a convict or claims that all who are incarcerated “must have done something,” they become complicit in the Nickel Academies of the world. As long as brutality in our prisons is society’s default solution to criminal behavior, we cannot act surprised when corpses surface in an institution’s dumping grounds.

The Nickel Boys, by Colson Whitehead. New York: Doubleday. 2019. 224 pages. Hardback, $24.95.

An Evening With Colson Whitehead. 8 p.m. Friday, July 26, at the Adrienne Arsht Center, 1300 Biscayne Blvd., Miami; 305-949-6722; arshtcenter.org. Tickets cost $35.