For all the frustrations that 2017 has brought, the realm of queer cinema has been full of features that have thrilled, chilled, and fulfilled every expectation. Though most conversation this upcoming awards season will turn to the quaint, romantic coming-of-age drama Call Me by Your Name, the year's other lovely cinematic works deserve recognition too, including films with LGBT characters proudly presented onscreen and mainstream films that read as queer in their content, themes, and subtext.

Here are the ten best queer films of the year, in no particular order.

Professor Marston and the Wonder Women. Do you love Wonder Woman? Well, here's a biopic about the man who wrote her to life and the women who helped craft her existence. Angela Robinson's gorgeous Professor Marston and the Wonder Woman might seem like a conventional biopic from a distance, but it's an astoundingly subversive work of art in its portrayal of the queer relationship among William Moulton Marston (Luke Evans), Elizabeth Marston (Rebecca Hall), and Olive Byrne (Bella Heathcote). In adhering to the conventions of what a biopic might look like, Robinson not only explores polyamory but also injects the past with all the bondage and gleeful sexuality that doesn't need to be kept in the shadows. This film understands what Wonder Woman truly represents, showing that she's not all about swords and action, but about how submission, love, and an intelligent, emotional dialogue can solve so many problems.

Paris 05:59: Théo & Hugo. If queer bodies on display are what you want, look no further than Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau's stellar Paris 05:59. Opening with an 18-minute sequence in a Parisian sex club that includes plenty of nudity, the film quickly becomes a romance in the style of Richard Linklater's Before trilogy. Geoffrey Couët and François Nambot, who play the titular Théo and Hugo, have such wonderful chemistry as they walk, bike, and talk throughout the city, all while being framed lovingly by the camera. Best of all is the way the film consciously explores a relationship between a man who is HIV-positive and one who is HIV-negative without an ounce of shame or criticism.

A Quiet Passion. After its early release this year, Terence Davies' A Quiet Passion has almost slipped under the radar. The film chronicles the life of American poet Emily Dickinson from her youth to her later years, covering her independent spirit, her reclusive nature, and her magnificent writing. Cynthia Nixon's tremendous talent and experience allow her to truly embody this woman who no one quite understands. Davies' script deftly shows how Dickinson shifted from witty to miserable. The poet's sexuality is never made explicit, but her admiration and interest in both men and women is implied, and her self-induced loneliness echoes that of numerous queer folks who felt trapped by the conventions of their time.

Princess Cyd. It's not a stretch to say that Stephen Cone's Princess Cyd is one of the most casual and loveliest films of the year. It tells the story of Cyd (Jessie Pinnick), a young woman who happens to fall for a girl in the neighborhood (Malic White) while visiting her novelist aunt (Rebecca Spence) over the summer. It's an absolute pleasure to watch Pinnick and Spence interact throughout the film, whether they're sunbathing on the lawn or discussing literature. And Cone's ability to show how queerness and spirituality intersect is rather beautiful, never critiquing any of his characters for loving what they love and finding happiness. As one of them says, "It is not a handicap to have one thing but not another, to be one way and not another. We are different shapes and ways, and our happiness is unique. There are no rules of balance."

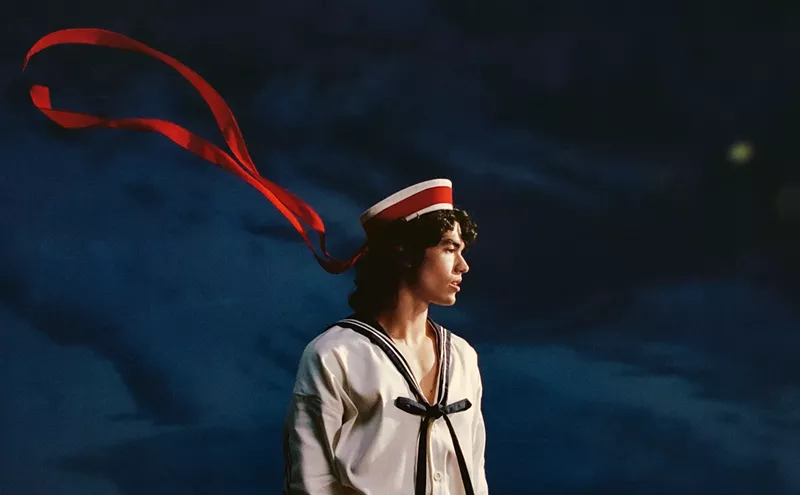

Beats per Minute (BPM). Robin Campillo's BPM is a film about bodies in motion, about people who are dying and those around them acting up to make a statement. Dropping us into ACT UP meetings in '90s Paris and then diving into the lives of the activists (many of whom are HIV-positive), the film rarely leaves us a moment to catch our breath. We watch the brilliant ensemble (including Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, Arnaud Valois, Adèle Haenel, and Antoine Reinartz) challenge and grow increasingly intimate with one another, and Campillo is as interested in showing their politically charged repartee as he is in exploring how these people love and make love. There isn't a single tragic cliché in this film about people who are dying; instead, it focuses on how to celebrate life while confronting death.

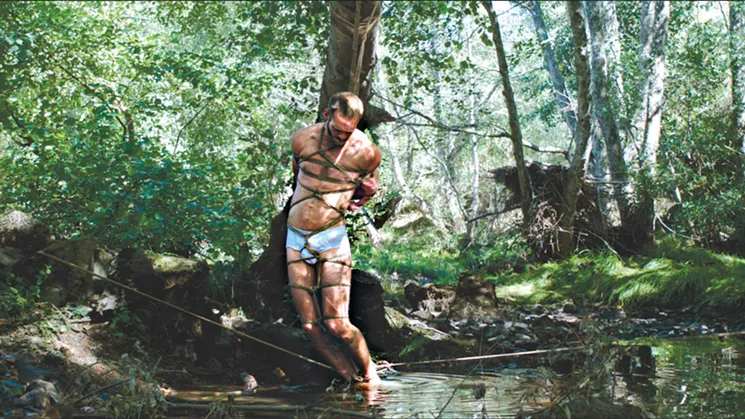

The Ornithologist. Indulgent in every sense of the word, João Pedro Rodrigues' The Ornithologist is as delicious and surreal as queer cinema gets this year. To put it simply, this is a film about an ornithologist, played by the gorgeous and talented Paul Hagy, who wanders through a forest and is subjected to numerous baffling and erotic experiences. Loosely based on Saint Anthony's journey, every minute of this movie is filled with Christian imagery (as well as visions of other cultures and religions) that teeters on a fine line between enlightening and blasphemous. It's not the nudity, bondage, watersports, and wound fingering that seduces the viewer, though; it's the gorgeous cinematography, the leisurely pacing, and the soundscape that washes over you.

God's Own Country. In contrast to the last film, Francis Lee's God's Own Country is pure realism. Sparking frequent comparison to Brokeback Mountain, this is a work that shows that sometimes relationships are as messy and frustrating as they are fulfilling and incredibly hot. Lee strikes a delicate balance in exploring how his protagonist Johnny (Josh O'Connor) deals with his self-loathing, sexuality, and family issues, while developing the romantic relationship between him and the Romanian farmhand (Alec Secareanu) in a tender and honest way. A work like this could easily slip into melodrama, but there's a sincerity in its presentation, and the chemistry between the actors makes every glance, glare, fight, and fuck feel natural.

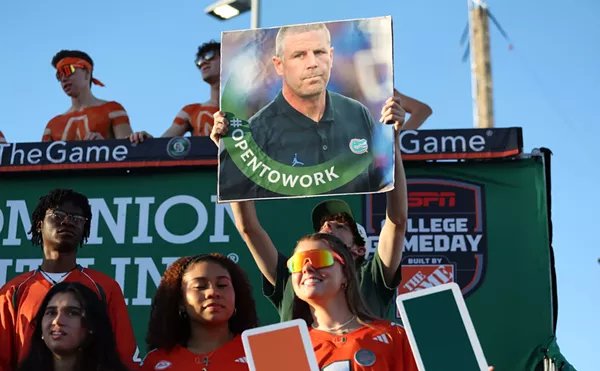

Battle of the Sexes. What might initially seem like a simple biopic about the famous tennis match between Billie Jean King (played here by Emma Stone) and Bobby Riggs (Steve Carell) is so much more. Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris' film sets aside Riggs' antics to focus on King's life off the tennis court, particularly in how her relationship with her hairstylist Marilyn (Andrea Riseborough) unfolds. From the very first haircut, Stone and Riseborough make it seem as if they're meant to be together through their glances, their words, and their touches. Every shot of the two women onscreen speaks volumes about their relationship, and it's one of the most tender developments of a queer romance onscreen this year. It's a film that never betrays its characters for dramatic effect or a big fight, and it's a fiercely feminist and optimistic note that offers some hope in an age when it feels like the nation is regressing rather than progressing.

Atomic Blonde. Some might dismiss Atomic Blonde as nothing more than a frivolous action film, but David Leitch's riveting spy thriller is as subversive as it is action-packed. Rather than solely delivering gorgeously shot punch after gorgeously shot punch, Atomic Blonde critiques itself and other works of its genre while still adhering to many of its rules. Charlize Theron delivers another iconic woman with Lorraine Broughton, and her bisexuality provides a surprising emotional through-line to a spy story that could have been otherwise forgettable. Here we see James Bond in the form of a woman, and it's as sexy and compelling as you'd imagine.

The Shape of Water. Every fiber of The Shape of Water screams queerness. This is a film that respects and adores the "others" of the world, whether they're people with disabilities, people of color, gay people, or tall, attractive creatures held hostage in a government facility. Its main antagonist is a straight, white, privileged, middle-aged American man who sexually harasses women and tortures humans and creatures alike — so basically the peak representation of oppression. Guillermo del Toro delivers not only a gorgeous fairy tale made for the people on the fringes of society, but also a truly queer movie that nails the feeling of otherness, of being unloved, and of being trapped in a world that isn't meant for you. There's a love of sex, a love of classical filmmaking, a love of fantastic scenarios, and a love of horror on display here, and it all blends together to form a wonderful work of art.

Honorable mentions: François Ozon's Frantz subtly explores obsession and roleplaying. Todd Haynes' Wonderstruck lovingly shows how outsiders shape and tell their own stories. Matt Spicer's Ingrid Goes West dives into an identity crisis and the façades we erect to "fit in." Julia Ducournau's Raw tears apart sexuality and shows us a woman who consumes that which she loves and wants to be. Hurry and see them all.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "22004575",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "22595215",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "23181625",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17720761",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]