Dawn was still streaking the sky over South Beach when FBI agents silently surrounded the art deco fire station on Jefferson Avenue. For months, they'd been watching a small, dapper firefighter named Chai Footman as he accepted more than $7,500 in cash and free drinks to protect popular nightclub Dolce. Now, as joggers from Flamingo Park stopped to gawk, the feds swarmed the station, grabbing Footman by his suspenders and throwing him into a squad car.

The strange scene repeated itself a half-dozen times that April 2012 morning, as the FBI arrested six other city employees ensnared in the nine-month anti-corruption sting. Also booked was another firefighter, Henry Bryant, who'd betrayed his badge by smuggling what he thought were kilos of cocaine for envelopes of cash. The chief target was Jose Alberto, the city's lead code compliance officer, who threatened hefty code violations to blackmail businesses out of tens of thousands of dollars. The feds nabbed four of Alberto's underlings too.

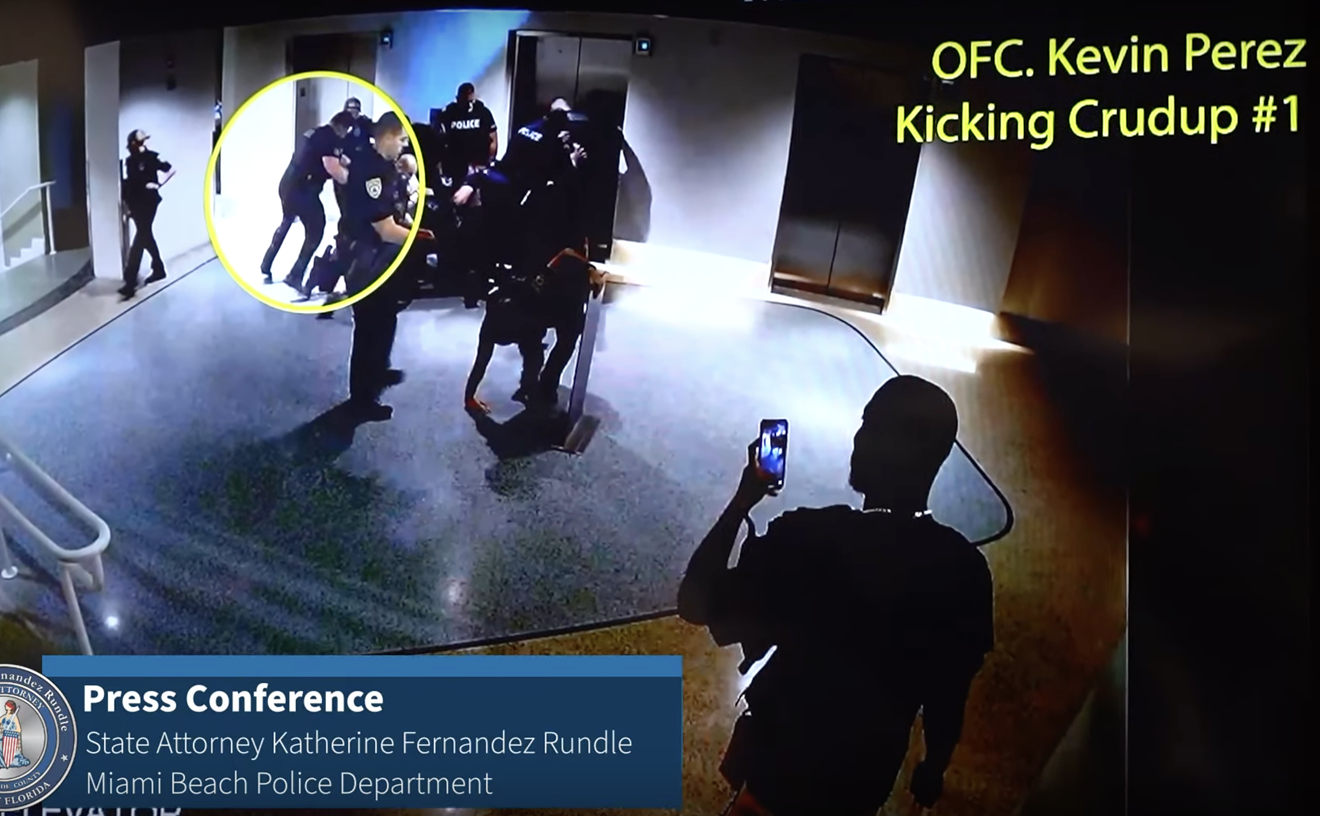

The arrests landed like a mortar in Miami Beach, a city already carpet-bombed by decades of corruption, and things have only gotten worse since City Manager Jorge Gonzalez resigned over the scandal. A bad cop was rehired despite beating up gay tourists. Miami Beach procurement director Gus Lopez was busted on 63 charges of demanding bribes for fixing contracts. Even Gonzalez's resignation was soured when taxpayers realized they owed him half a million dollars in severance.

By now, graft in this island city seems as endemic as sea oats. Brisk business, booming development, and a steady stream of tourism have so swollen the coffers that corruption appears almost inescapable.

But the reality is that the city has blown plenty of chances to clean up its act. Nowhere is this fact more obvious than in the Miami Beach Fire Rescue Department (MBFR), a force of 303 with a $62 million budget, the second largest in the county. Years before Footman and Bryant went astray, two employees — fire captain Edward Gonzalez and fire inspector David C. Weston — blew the whistle on rampant wrongdoing, only to be ignored, ostracized, and forced out.

A three-month New Times investigation has found strong evidence supporting the two whistleblowers' allegations. Dozens of interviews and hundreds of pages of documents reveal a department with suspect leadership, little oversight, and a playboy culture that has led to multiple lawsuits. New Times has discovered the following:

• Millions of dollars' worth of fire permit fees went missing or were written off by inspectors, including those now charged with taking roughly $25,000 from club Dolce.

• City officials ignored repeated, detailed warnings about those missing funds.

• Top fire officials were warned about inspectors taking bribes from a South Beach hotel to ignore thousands of dollars in code violations, but did nothing.

• One powerful fireman, union president Adonis Garcia, has been accused of three assaults, bilking the county out of $76,000 in property taxes, and abusing his authority as a firefighter.

• A female firefighter successfully sued the department over repeated sexual harassment, including semen-stained clothing and death threats, winning $700,000.

• An African-American recruit was awarded $100,000 after alleging racial abuse, including being teabagged and called racial epithets by fellow firemen.

Taken as a whole, the facts paint the picture of a department wracked by corruption and racial and sexual abuse, 20 years after the Department of Justice sued to stop MBFR's discriminating ways. Amid these problems, Javier Otero, the department's chief, has continued to rely on bad apples like Garcia, a man who is now a captain and the department's spokesperson.

Otero disputes New Times' conclusions and says he takes seriously every complaint that reaches his office. "I don't have any reason to believe there is corruption in the department," Otero says. "These are nothing more than allegations from disgruntled employees."

Garcia also defends his record. "I've done nothing but try to do the right thing," he says. "At the end of the day, I've got nothing to hide."

But where there's smoke, there's fire, and thick plumes of scandal hang over MBFR. As Footman prepares to join Bryant in federal prison, the department's two whistleblowers are demanding to know why their supervisors aren't also behind bars, or at least out of jobs.

"There are so many lies and so much bullshit coming out of the department," says Gonzalez, the retired fire captain. "And it all starts at the top."

Holding a clipboard, David Weston walked through the splendor of the Fontainebleau's foyer. Beneath his brown wingtips lay a small fortune of new Italian marble tiles. Above his head glimmered golden crystal chandeliers. And all around him swirled the buzz of the mind-boggling $1 billion renovation.

But as the Miami Beach fire inspector roamed the palatial hotel, his thoughts were on the figures he couldn't see. Despite the historically expensive renovation, the city had valued the construction at just $115.5 million. That meant the city was losing out on millions of dollars in permit fees, Weston realized.

"It was ludicrous," he says. "And suspicious."

Weston soon began to notice other projects that seemed to be deliberately undervalued and fees left uncollected. But his complaints were ignored, and in 2008 he was suddenly axed. "They had something to hide," he says. "And they still do."

Weston's tale, which has never been reported before, demonstrates how building, code, and fire officials had ample opportunity for graft. It also shows how, despite five years of allegations reported to police, the Inspector General's Office, state prosecutors, county auditors, and FBI and Florida Department of Law Enforcement agents, nothing has happened.

Yet New Times found ample evidence — from permit records to audits, insider testimony to arrests — that bolster Weston's claims. "They fired me to silence me, and they timed it to embarrass me," he says.

David Weston was destined to be a pain in someone's ass. His ancestors fought in the American Revolution. His dad was a military intelligence officer during World War II. Young David, who was born in 1950, inherited his old man's intellect and single-mindedness. When legislators threatened to cut funding for the student radio program at his high school near Philadelphia, he wrote an angry letter demanding it remain on the air. It didn't hurt that he let politicians think he was another David Weston: the then-president of ABC.

Weston attended the University of Miami to study engineering. In 1999, he joined Miami Beach Fire Rescue as a fire protection analyst. The job suited his obsessiveness. Weston drove around the island inspecting construction and renovation projects to ensure the plans were followed and that alarm and sprinkler systems worked. When he discovered problems — such as faulty doors that could turn a building into a towering inferno — he issued violations and withheld permits.

Weston was one of only five full-time fire protection analysts. But there were also about 30 fire inspectors, many of them firefighters such as Chai Footman, who moonlighted by checking nightclubs for overcrowding. Altogether, the fire prevention bureau was responsible for inspecting Miami Beach's thousand buildings once per year and levying millions in annual permit fees and fines.

In 2003, Sonia Machen was hired as the department's fire marshal in charge of inspections. She introduced computers equipped with a new, digital system called Permits Plus. It was designed so departments could share information and inspectors could raise permit costs as building costs increased.

The change came as Miami Beach enjoyed an unprecedented boom. Weston and his counterparts could hardly keep up with inspecting all the new high-rises pumping billions into the economy. "I started noticing that the building department wasn't doing a good job assessing fees on Permits Plus," he says. "Taxpayers were getting cheated out of millions."

Weston spent months inspecting renovations at the Fontainebleau, for instance. According to him, permit fees for the $1 billion remodeling should have totaled $25 million, or roughly 2.5 percent. Instead, contractors paid just under $2 million.

There were other undervalued projects. Once, Weston took the ferry to exclusive Fisher Island to inspect a 16-story building on the north shore. But the permitted cost was only $20 million. When he complained, his supervisors revalued it at $58 million, raising fees three-fold. The developer warned Weston not to return to the über-rich isle.

As with the Fontainebleau, the renovation of the Eden Roc hotel struck Weston as suspicious. Developers touted it as a $240 million project, but Permits Plus records listed only $51.56 million worth of construction between 2004 and 2010. That would have meant $188 million was spent on furnishings — a ridiculous $300,000 per room.

Weston suspected that someone with access to Permits Plus had deliberately undervalued each of those projects to save the developers millions in permit fees, perhaps in exchange for kickbacks.

But whenever Weston complained to Machen or her assistant Steve Phillips, they told him things were under control. Finally, in 2007, Weston broke the chain of command by going to Miami Beach internal auditor James Sutter and laying out his suspicions. "You know you'll probably be fired for this," Sutter said, according to Weston. (Sutter did not respond to requests for comment.)

By February 2008, Weston was so fed up he went directly to then-Chief Edward Del Favero and threatened to alert the cops. Before he had a chance, though, Miami Beach police arrested three building department employees on corruption charges. Planner Henry Johnson, plans examiner Mohammed Partovi, and inspector Andres Villarreal were caught accepting bribes stuffed inside toilet-paper rolls in return for fast-tracking a developer's plans.

Two days following the arrests, Weston was fired after an anonymous letter arrived claiming he'd started a company with a permit consultant named Damian Gallo against city policy.

Weston had indeed bought a 17 percent stake in a marina venture in which Gallo was also an investor. But Weston had asked the Miami-Dade Ethics Commission if the investment was OK and insists he also notified his superiors. Yet Machen wrote that the deal was "unacceptable" in Weston's termination letter.

"That wasn't really the reason why they fired me," Weston maintains. "They wanted me to look guilty, like I was part of the group [with Johnson, Partovi, and Villarreal]."

(Machen admits to New Times that soon after Weston left, Permits Plus was changed to standardize permit fee procedure.)

Weston had good reason to suspect that inspectors were taking cash to ignore permit fees. Two years earlier, electrical inspector Thomas Ratner had been busted for corruption. Then there were the arrests of Johnson, Partovi, and Villarreal.

In a memo, then-City Manager Jorge Gonzalez partially blamed the arrests on Permits Plus, which, he wrote, "does not contain an 'audit trail' function. This meant that job value... could be changed... by a single individual without the system recording."

The scandal vindicated Weston. "I think the city has become a racketeering-based, corrupt organization," he says.

As for the missing millions in permit fees, "there are three possibilities as to what was going on," Weston says. "First, that contractors lied about the values and that clerks were too stupid to know. Second, they were scriveners' errors. Or third, there was fraud going on."

Weston has met with officials from the FBI and the Miami-Dade Police Department's Public Corruption Investigations Bureau to discuss his complaints. It is unclear if either agency is investigating. Miami-Dade Police did not return calls from New Times. The FBI declined to comment.

Mid-interview, Weston rummages through his bag and pulls out something shiny: a 1944 Canadian victory nickel. Like corruption, coins are an obsession of his.

"Cities are like money," he says, holding up the coin to show the Morse code embedded in its edge. "They are full of hidden things."

Captain Ed Gonzalez sat in front of his home computer. His stocky firefighter's frame perched precariously above a keyboard as his thick fingers pecked words of outrage. It was just before midnight September 10, 2012.

"Accept this as my official forced letter of resignation," he typed.

At the time of his resignation, Gonzalez was the fourth highest-ranking member of the department. But he'd had enough.

The details of Gonzalez's allegations — which, like Weston's, have never been reported before — suggest that fire officials ignored evidence of bribery. Gonzalez had witnessed a hotel manager in South Beach detail his entanglement with a bribery scheme, and then watched in dismay as nothing was done about it. Meanwhile, Gonzalez's own job was brought to a screeching halt as he tried to blow the whistle.

"One hell of a way to end a career," he wrote in his resignation letter.

Gonzalez had joined the department the same day Otero, the future chief, had arrived: January 16, 1989. Gonzalez was born in Key West and still bears the laid-back attitude of a Conch. His dad was a doctor who insisted his kids get a good education in Miami, so Ed studied accounting at St. Thomas University. He became a sales rep at AT&T but grew bored. He saw an ad for the fire department. At 40 years old, he arrived at training a decade older and a few pounds heavier than the other recruits.

Otero, on the other hand, was a lean and handsome Colombian-American. Just out of the Army, Otero made no effort to hide his ambition. "He came in with the full intention of becoming the fire chief one day," Gonzalez says. "He said as much. All the time."

The two became friends while serving on the same rescue teams. They trained together, put out fires together, even lived together in an apartment near South Shore. "I introduced him to his second wife," Gonzalez says of Otero. When Gonzalez and his wife celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary, the Oteros attended.

But the friendship began to fall apart in February 2011. That's when a routine inspection pulled back the veil on widespread bribe-taking, Gonzalez says.

It started with a routine call to a construction site at 34th Street and Collins Avenue. He was met there by Armando Perez-Roura Jr., the son of the powerful Radio Mambí talk-show host of the same name. Junior had been busted in 1984 for importing cocaine from Colombia, but served just two years after becoming a government informant, according to a 2004 New Times report. Now he was trying to go legit as the manager of the Versailles Hotel Condominium.

"He just opened up," Gonzalez remembers. Perez-Roura Jr. told the fire captain that he and other condo board members had paid thousands in bribes to fire inspectors and other city officials to expedite renovations. But the bribes hadn't worked.

"It was like, Oh crap. What do I do now?" Gonzalez remembers thinking. "I didn't want to walk away, but also I couldn't go to my supervisors."

Instead, Gonzalez called the Miami Beach Police Department's Strategic Investigations Unit — the unit that had busted corruption within the building department three years earlier. On February 28, 2011, Gonzalez accompanied Dets. Rosa Redruello, Alkareem Azim, and Debra Travis to the Versailles.

(New Times obtained a redacted copy of the intelligence report on that meeting. Asked for an unredacted copy, the Miami Beach PD refused on the basis that the information could expose an undercover officer. The details below come from the redacted report, except for Perez-Roura Jr.'s identity, which he confirmed in an interview with New Times.)

Here's what Perez-Roura Jr. told detectives: A fire had damaged the building in 2005, so inspectors informed the Versailles owner he'd have to hire an architect. The condo board hired Reymundo Miranda of UCI Engineering to do the job.

Miranda soon approached the wife of the condo's board president and told her he needed $15,000 to "pay off city officials," according to the report. "Perez-Roura Jr. said he personally delivered $15,000 cash to Miranda, who told him that the money would insure that the City would 'leave them alone.'"

Perez-Roura Jr. also told detectives that he had met Miranda on several other occasions at the Latin American restaurant on 41st Street and paid him $2,000 and $3,000 to bribe city officials. The Versailles received various violations while Miranda was the engineer of record, Perez-Roura Jr. told detectives. But each time, they were dropped.

Then, in 2009, Miranda insisted the building needed a new fire alarm system. He arranged for another company to do the work for $70,000.

But after the system was installed, another inspector put the Versailles on fire watch because no permit had been issued for the work. The fire inspector — whose name was blacked out in the report — later took Versailles off that watch list, even though there still was no permit, presumably because he too had received money, Perez-Roura Jr. told detectives. The same inspector had also "signed a form stating the alarm installation job cost $1,000 (instead of $70,000)."

The Versailles was in shambles, but under protection thanks to the bribes. When another analyst found holes knocked clean through walls, hotel management simply said Miranda already knew about it, and no citation was given.

When the Versailles finally fired Miranda in 2009, the city issued a stop order on all construction until the hotel hired another architect. But when the new architect resubmitted the plans that Miranda had already had approved, they were rejected. The fire department suddenly found no less than 67 violations. Perez-Roura Jr. tried to speak with officials in the fire and building departments but was told "someone" had put a hold on the project.

(Rey Miranda adamantly denies ever paying a bribe. "That is a total lie," he says of Perez-Roura Jr.'s claims. "Anyone can accuse anyone of anything. Talk is very cheap. You have to ask yourself: How does someone benefit by throwing an accusation of that nature out there?")

Listening to this story, Gonzalez was aghast. "It just stank to high heaven," he says. "It sounded like someone was writing these [violations] off in order to get a payoff or at the orders of someone higher up."

On March 16, 2011, Dets. Azim and Travis met with then-Assistant State Attorney Joe Centorino to discuss the bribery accusations. Centorino told them that "no criminal activity [was] evident," according to the Special Investigations Unit report.

Perez-Roura Jr. also claims to have corresponded via email with Otero and Fire Marshal Sonia Machen regarding the corruption.

(After initially saying Perez-Roura Jr.'s name "did not ring a bell," Machen later emailed New Times to say that she did, in fact, remember Perez-Roura Jr. and that his allegations were "totally false" and "an attempt to discredit [her] so that the condo association would not have to incur the cost it would have taken to correct the fire code violations.")

"You know what I really don't understand?" Perez-Roura Jr. says. "I believe they have enough to do a real investigation, but I haven't seen them do anything."

Gonzalez was also stunned by the inaction. "I kept waiting to hear back about the case, but there was nothing." It didn't help that the new police chief, Ray Martinez, disbanded the Special Investigations Unit when he took over in March.

Even though no one was ever charged, Gonzalez believes his career was wrecked by taking the allegations to the cops. His performance evaluations plummeted, and his health began failing. "My life became miserable," he says.

Gonzalez finally quit after getting into a tit-for-tat September 5 with an assistant fire chief who suspected Gonzalez and another firefighter of tape-recording a meeting with him. Furious over the inaction and the hostile treatment, Gonzalez went home and typed up his resignation letter. He estimates he gave up $200,000 by leaving early.

"I couldn't take that type of harassment anymore," he says. "I was going to end up having a heart attack with all the games they were playing."

Yuri Moros's running shoes slapped the Venetian Causeway concrete. It was a blazing-hot August afternoon in 2005, and the Venezuelan professional trainer was staying in shape. Life was good. Business was taking off. Pop star Ricky Martin had endorsed his workout regimen. And Moros had recently gotten married.

Suddenly, Moros heard a screech. A silver Hummer had pulled a U-turn and was slowly following him. When he glanced over his shoulder, he saw a familiar figure shouting angrily — his wife's ex-husband, Adonis Garcia.

Moros was all too familiar with the six-foot-three firefighter who seemed to relish opportunities to intimidate his replacement, so he turned up the volume on his iPod and tried to ignore him. Instead, Garcia reached into his glove compartment and pulled out a handgun, according to a police report. Then he aimed it at Moros, who fled down a side street. Garcia was charged with aggravated assault, though prosecutors later declined to pursue the case.

In the years since, Garcia has risen from rank-and-file firefighter to one of the most powerful members of Miami Beach Fire Rescue: a captain, a union president, and even the department's official spokesperson.

But Garcia's personal travails echo the problems that have multiplied under his and Otero's leadership, as the department has been rocked by scandals, firefighter arrests, and two lawsuits over sexual and racial harassment.

"Adonis is politically savvy and powerful," says city Commissioner Ed Tobin. But he is also, Tobin adds, one of the reasons the department has "been flushed down the toilet."

Garcia defends his record, and Otero sticks up for his employee. "I know there have been several accusations about Adonis... but they have been properly looked into and investigated," Otero says.

Garcia, like Gonzalez a Key West native, joined the department in 1994. Ten years later, on August 1, 2004, the then-38-year-old firefighter was at the popular South Beach nightclub Mynt when he got into an argument with Santiago Contreras. Garcia slugged the businessman in the mouth, leaving a gash that required seven stitches, according to a police report. Garcia was arrested, but the charges were dropped days later.

Four months later, Garcia was busted again, in Monroe County. This time, he was accused of assaulting a law enforcement officer. Yet those charges were dropped six months later.

Finally, there was Garcia's arrest August 23, 2005, for allegedly brandishing a gun at Moros. The trainer had recently married Sabrina Moore, Garcia's ex-wife. The two men even looked alike: dark-haired, handsome, and ripped. Garcia disputes the claim. "I would never do that," he says. "I don't even own a gun. Obviously, nothing really happened."

The assault charge was quashed.

Eventually, though, Garcia's problems caught up with him at work. On February 3, 2007, the firefighter was hired as a paramedic for a Volleypalooza tournament on the beach at Eighth Street. Garcia misrepresented himself as the "fire marshal," according to a letter that event organizer Lana Bernstein sent to the city's special events coordinator. Instead of working, Garcia got busy "bringing his guests onto [the] event stage." When staff asked him to stop, he demanded that the event be shut down. Garcia seemed "pumped up" and "hard-line," Bernstein wrote.

The next night, he again "was bullying and assaulting [the] staff," the organizer wrote. Finally, Bernstein claimed, "Garcia was seen in the party acting as a guest and enjoying himself, as opposed to supervising and assisting any city staff."

Garcia says the event got "out of control" and he had to forcefully intervene, but calls the other allegations "absolutely false."

Garcia has also been accused of defrauding the tax system. This past December, Miami-Dade County filed a lien against his house after determining he'd claimed $76,000 in homestead exemptions on his $600,000 Normandy Shores Golf Course Club property despite renting it out and living in a SoBe condo.

The firefighter says he was "shocked" at the penalty. He admits he doesn't live at the Normandy Shores home but says the lien is a misunderstanding he's working to fix.

Garcia certainly isn't short of cash. As union president and department spokesman — jobs that make him the face of MBFR everywhere from MTV segments to local TV reports — he pulls in significantly more than his $95,000 annual base salary (plus tens of thousands of dollars in benefits). It's unclear exactly how much Garcia really makes. He declined to say.

As union chief, he helped engineer last year's $60 million pension bill — a deal that paid him handsomely. On September 1, the then-second-level firefighter was promoted to lieutenant, receiving a $4,200 raise in yearly salary. Less than a month later, he was promoted to captain, receiving another $4,600 pay bump. When he retires, the deal guarantees he'll receive at least 65 percent of his salary as pension for the rest of his life.

He was one of six firefighters to get a double-jump when the city signed a new contract, which critics, such as Commissioner Tobin, say will cost the city millions in the long run in new pension obligations. "The presentation of the [contract] was designed to fool some commissioners and the public into thinking this was paid for," Tobin says.

Otero and Garcia have also been criticized for the culture of their department, as multiple complaints of sexual and racial harassment have arisen.

Last year, an African-American fire recruit named Brian Gentles claimed to New Times that a white colleague repeatedly called him "nigger" and put his testicles on Gentles's face. Gentles had met with Otero in December 2011 to discuss the alleged abuse. The then-assistant fire chief acknowledged that several other recruits confirmed the complaints, Gentles says. But when Gentles began to give a recorded statement a few days later, Garcia allegedly stopped the tape, took him outside the room, and told him not to "snitch" or he would be fired.

Indeed, Gentles was eventually axed. He filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and eventually accepted a $100,000 settlement to return to the department as a fire inspector. (A city investigation, meanwhile, determined his claims were "not credible.")

"It seems like it's the Wild Wild West," Gentles says of the department. "You can do whatever you want — the taxpayers are just going to pick up the tab. Be racist, be sexist, no one is going to say anything."

Marlenis Smart echoes that sentiment. Smart says she was sexually harassed from her first day on the job as a firefighter in 2005. In her suit, she claimed male firefighters told her "women belong in the kitchen," accused her of being a slut, and walked in on her in the shower. Smart, who is married with four children, says Otero once even called her "promiscuous." One time, her underwear was stolen from her locker. When she found it, it was covered in semen, she says. Her bra was hung from the rafters.

She also says she received death threats. When Smart pulled her bag out of her locker one day, out fell a photo of her with the eyes crossed out. "Liar," was written under her face, along with a warning: "Next fire last fire."

Smart filed her lawsuit in federal court in 2010.

Asked about Gentles and Smart, however, Otero declined to comment to New Times. "My interest is in moving forward, not continually rehashing things."

"His theory was that none of this crap happened," Smart counters. "He told me that I lied in court, when he's not even supposed to be discussing the trial." She claims Otero also sent her "really nasty emails," including one that accused her of "playing games."

"Can you believe this is the fire chief?" she says.

Ed Gonzalez was apoplectic when then-City Manager Jorge Gonzalez appeared at David's Café in South Beach before a crowd of residents and claimed he had nothing to do with last April's corruption arrests. Like many residents, he was furious when the city manager walked off with a half-million-dollar severance package a few weeks later.

But the firefighter knew the real damage had already been done. Because Otero and other fire officials had ignored his and David Weston's complaints, city employees had continued to extort tens of thousands of dollars from business owners for years until the federal arrests. Millions in permit fees potentially went uncollected.

Worst of all, those responsible for the corruption might never be punished. First, there is Jorge Gonzalez. After the 2008 building department arrests, he insisted the Permits Plus system had no audit function. But several reports showed it did. He also promised to crack down on employees abusing the system. He didn't.

An audit released earlier this month shows that years after the arrests — and half a decade after Weston first raised concerns about the system — employees danced around the Permits Plus controls with ease. For instance, the database failed to red-flag the fact that Chai Footman and Henry Bryant had issued just one violation in their last 1,423 inspections — an obvious sign they were looking the other way.

More than $184,000 in fines were removed from accounts without proper documentation, the audit continues. Half were removed at the whim of one person without supervision, the other half by the city's lead code administrator, Jose Alberto.

But what really rankles Weston is that the abuse is exactly what he warned about back in 2007. In fact, the author of the recent report, internal auditor James Sutter, was the very person to tell him he would "probably be fired" for raising concerns. The alleged corruption also mimics the information Ed Gonzalez took to police in 2011.

Jorge Gonzalez, though, deflects any blame for the corruption crisis on the Beach.

"Me not being city manager today has nothing to do with corruption. I'm no longer city manager because of politics," he says. "I'm an easy target [because] I left. They feel like they have to blame somebody. People can accuse me of being corrupt, but there hasn't been one lick of evidence, because it isn't there."

Both whistleblowers also partially blame Otero for the ongoing corruption scandal. "As assistant chief back then, Otero would have been the person doing the investigations, so he bears the responsibility," Ed Gonzalez says.

But Otero says he never spoke to Ed Gonzalez about his meeting with police and learned of it only after Gonzalez quit. The fire chief also refused to sit down with New Times to go over police reports about the Versailles bribes. Likewise, Otero claims to have no knowledge of Weston's complaints about missing permit fees.

"I have no indications that there is corruption within the fire prevention bureau," Otero says. "The FBI did a very thorough investigation, and they arrested the only two that were stupid enough to bite the hook," referring to Footman and Bryant.

Otero says that if his department has a reputation, it is for being "hard-asses, by the book, who don't know how to interpret code to help businesses."

Weston and Gonzalez say they won't believe the department is clean until Otero, Machen, and others are gone. The two would like to see a serious investigation into Jorge Gonzalez, whom they suspect knew about their complaints but quashed them.

"They had a chance to put a stop to criminal activity," Weston says. "Why didn't they? I don't know if I'll ever get an answer to that question."

Each whistleblower is now weighing his future. Ed Gonzalez is preparing a lawsuit over his forced resignation. Weston, meanwhile, would like a chance to clear his name and scrub the city clean. He says he has been in discussions with Miami Beach city manager candidate Jimmy Morales about being appointed to a special anti-corruption post. "I'm going to go in there and tell them who the skunks still left are."

As part of his settlement agreement, Brian Gentles is now working as a fire inspector. But his job will last only 17 more months, and he is considering further litigation. Marlenis Smart, meanwhile, was awarded $700,000 by a federal judge last March. However, the city is demanding a new trial, and she has yet to see any of the money.

Miami Beach residents better hope that Otero is right and that the graft in his department has been nipped in the bud. Because the boom years are coming back to SoBe: Luxury condos are setting sales records, and new buildings are again sprouting all over town, particularly around Sunset Harbour. If he's wrong, the Beach could soon be a corruption free-for-all.

It might already be, if one particularly knowledgeable source is to be believed.

"There's a lot more to it than what's been said," Chai Footman confessed to New Times a few weeks before beginning his eight-month sentence in March for accepting bribes. (Henry Bryant, who smuggled the fake cocaine, is serving 20 years in federal prison.)

Asked if corruption extends beyond those arrested, Footman answered, "That's a pretty good assumption.

"All you have to do is be out there at the clubs at night," he added. "Watch the fire inspectors as they go through and do their stuff. Whatever you are looking for, you'll find it."