Last week's "How One Famed Hollywood Restaurant Became the National Center for the Mob" catalogued the rise of Broward's Gold Coast Restaurant as the Southern headquarters for the mob. This is the conclusion.

If Joe Sonken's Gold Coast Restaurant was the white whale for law enforcement in South Florida, Lt. Dave Green was its Ahab. Green was a hardworking dynamo in Broward's Organized Crime Division (OCD) and a 20-year veteran of police work. As part of "Operation Cherokee," which began in June 1985, Green was assigned to go undercover at Gold Coast as a shady liquor hijacker. His alias was Danny Ledford.

So one day in that summer of '85, Green glided up to the Gold Coast valet in a black Lincoln Continental. The stout 46-year-old, wearing gold chains and a lot of polyester, blended well with the mob associates — much like undercover FBI agent Joe Pistone, AKA Donnie Brasco, had fit in at Gold Coast a few years earlier.

A plan to gain access to patrons through one of Sonken's employees, bartender Patrick DeCrescito, fell through when the parolee slipped back into criminal activity and left Gold Coast. But Green hit pay dirt with Anthony "Guv" Guarnieri, a capo of the Pennsylvania-based Bufalino crime family who held a special place in mob history, having attended the legendary 1957 Apalachin Meeting of Mafia chieftains. Green came to genuinely like the 74-year-old Guv, who looked grandfatherly in his usual felt cap. "He is an old-school mobster," Green would say later, "a gentleman." Guv's wife Ann even treated the cop as family.

Green tried to be seen as much as possible with Guv at the tables in the Gold Coast's cavernous dining room and smoky lounge. That way, other mob figures, who would greet Guv with a kiss of respect on the cheek, would trust the newcomer. Green noted the wide range of Mafia crews he met, later commenting about Broward County: "We've definitely become the headquarters for the mob."

As Green's contacts in Gold Coast's well-armed Mafia crowd expanded, danger closed in. When the undercover lieutenant placed a bet with Richard DelGaudio of the New York-based Gambino crime family, the bookie asked if Green knew what happened to people who didn't pay gambling debts. Then he put his finger to the cop's head and "cocked his thumb," Green later told the Fort Lauderdale News.

One day in early 1986, Mark Potok, a then-30 year-old reporter for the Miami Herald, visited Gold Coast — very possibly walking by new regular "Danny Ledford" — and sat with Sonken in his office. A cylinder of salami hung from a nail in the wall, and fat dripped down into a bowl that rested on the desk. Nearby was a long knife used for cutting slices. A rickety elevator in the back of the room led to liquor storage and offices. A poster above Sonken's chair pictured a bulldog and the caption "When I want your opinion, I'll beat it out of you." "Hollywood was infamous as a Mafia retirement hangout, though [the mobsters] were beginning to die off," Potok recalls today. "I was uptight to be in there."

Potok was reporting on a large donation, "quite a sum" in Sonken's words, that the restaurateur had made to Nova University, which was then still almost a decade away from combining with Southeastern University of Health Sciences and becoming the research mecca it is today. The money was earmarked for Nova's high school, the University School. "Neither Sonken nor University School officials will say how much Sonken donated for the building, which is to be the school's first high school building," Potok wrote. "At present, some 300 high school youths are taught in a building of the parent university, which shares the preparatory school's grounds."

Sonken, slumping at his desk, listed one reason for the donation as multiculturalism, or at least his version: "They got whites, they got Jews, they got coloreds." The restaurateur grew angry when Potok asked about the litany of past allegations against him. "'Frame-ups,'" he snarled. "He was not happy at all that I confronted him," recalls Potok, who has a clear memory of that meeting 30 years later. "The whole thing was bizarre and frightening."

At the time, Nova was strapped for money and in a risky phase of expansion and transition. Joseph Randazzo, then headmaster of the University School, dismissed the reporter's questions about Sonken. "We know nothing of his past other than that he's a fine, upstanding businessman in the community," Randazzo said. Nova's then-president, Abraham Fischler, years later spoke more openly. "Everyone thought it was a bad look," Fischler admitted in 2009 as part of an oral history project. "Sonken was a man who had a reputation for being part of the Mafia."

Exactly why Sonken chose the University School for his donation, neither he nor administrators ever really addressed. Sonken might have shed some light on the subject during the groundbreaking, but questioned about whether he would attend, he grumbled, "Nah, I ain't going!"

It was all part of the great contradiction that was Joe Sonken.

Lieutenant Green wore a recording device strapped to his back as he made the rounds at Gold Coast. If anyone tried to pat him down, he would curse like the street tough he was impersonating. "If you don't like me, don't do business with me," he would say.

Other undercover officers, including Det. John Sampson of the Broward Sheriff's Office, would shadow Green in case he got in trouble. Sampson had conducted extensive surveillance on Gold Coast and could recognize specific wise guys from the backs of their heads (he actually kept a book of photos of backs of heads). "There was always that danger of recognition" from Green's past undercover operations, Sampson told Knight Ridder. If backups had to intervene, the plan was to pretend to arrest Green.

One day, an old friend of the undercover cop's walked into Gold Coast's bar area, the Cutty Sark Lounge, where the detective shared a table with a big, burly hood named William Spatuzzi. The friend called out: "Hey, Dave, you still a cop?" Green made eye contact with his backup, BSO Dep. Theodore "Pete" Stephens, who prepared to act. But Spatuzzi didn't hear the greeting, and Green's friend moved on.

Over the next months, Green heard that Russell Bufalino — head of a crime family — would visit Gold Coast every day when he was in town. Philadelphia mob boss Nicodemo Scarfo also traveled to the restaurant from the mansion he kept in Fort Lauderdale. Powerful bookies would call Gold Coast's phone to talk to patrons. Detectives also learned of Sonken's emotional life — how he "fell apart" when a friend died of cancer.

In fact, the usually ill-tempered Sonken's softer side often snuck out with staff and customers. One day, when a busboy found a balled-up ten-dollar bill and reported it to Sonken, the boss responded, "Shut the fuck up and go to work," his way of leaving the kid a bonus. Another time, the restaurateur paid for an employee with back problems to travel to Minneapolis to see a specialist. And, indeed, Sonken had been so wounded by his mother's death in 1967 that he gave a standing order to musicians never to play "My Yiddishe Momme," a sorrowful Jewish lament for a lost parent.

So which was the real Sonken?

If anyone tried to pat him down, he would curse like the street tough he was impersonating.

tweet this

The first salvo against the restaurateur was Jack Anderson's 1957 so-called exposé of Gold Coast. Anderson, a nationally syndicated columnist, wrote, "Arriving hoods check in at the Gold Coast lounge." Then he coined a description that stuck: "This appears to be the underworld message center in the Miami area." The article focused on an "unlisted" phone behind the bar and a phone booth in the corner used for communication with "mob chiefs in New York, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Los Angeles." Sonken, whom Anderson described with juvenile meanness as "blimp-bellied," arrived from Chicago as a veritable mob capo: "The 250-pound Sonken muscled in temporarily on the local Plaster Tenders, Hod Carriers, Construction and General Laborers Union." Various newspapers attached provocative headlines to the stories: "Secret Hideout Exposed" and "Meet Blimp-Belly Joe."

Never mind that Anderson, an ethically dubious journalist desperate for big stories, was fed his information by a rival restaurateur of Sonken's. That fact didn't stop journalist and politician Pierre Salinger from calling out the "notorious" Sonken in 1959 hearings on criminal rackets conducted by Sens. Robert and John F. Kennedy. Salinger repeated Anderson's fanciful assertion that Sonken controlled South Florida labor unions. In 1961, hardboiled writer Hank Messick visited Gold Coast. "The telephone — the same one described by Jack Anderson in his 1957 column — rang loudly," Messick recounted in 1968's Syndicate in the Sun. "The bartender picked it up, then circled the bar and went out into the dining area, where a short, fat man sat alone at a table. He whispered in the man's ear, and I watched Sonken put aside his cigar and waddle back to the telephone... The telephone conversation was one-sided. All Joe did was grunt. Then he went back to his table." Never had a telephone call looked so sinister.

Sonken cultivated his colorful persona for the public. He kept a Prohibition-era Tommy gun on display in his office. The restaurateur's portly build, rumpled style, and chunky cigar gave him the look of a Chicago gangster. Customers came to Gold Coast to see the mobsters who were glamorized in books and movies. Mafia mystique, in short, was great for business, with diners feeling, in the words of Sunshine magazine in 1985, like they were extras in The Godfather.

If investigators kept their distance, the mob would continue to serve up valuable intelligence.

tweet this

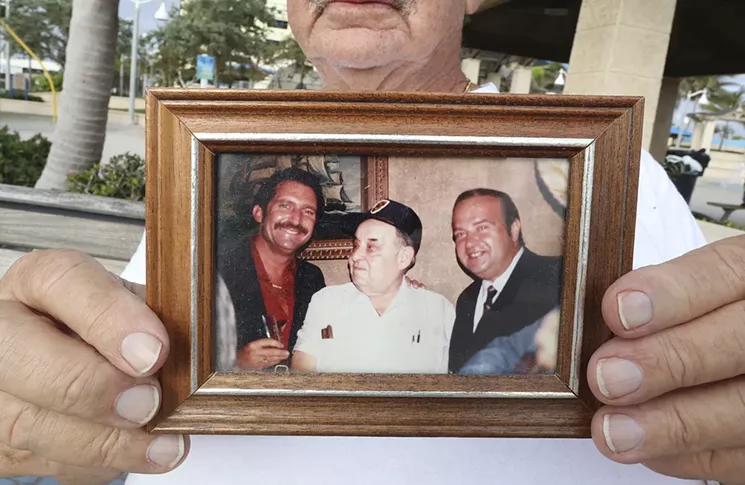

Larry Keller, a reporter for the South Florida Sun Sentinel in the 1980s, studied about a hundred pages of FBI files on Gold Coast and concluded that "Sonken seemed like an intermediary." The restaurateur made introductions, relayed messages and phone calls, and hosted gatherings. Some of these patrons, no question, were hoods. Others were doctors and music producers. Sonken also did favors for friends, and some were Mafiosi. Russell Bufalino's car, for example, was registered to the address of Gold Coast. And Buddy Lansky, Meyer's son, who amassed gambling debts, asked Sonken for an introduction to a loan shark. When friends asked Sonken for the identity of someone in the restaurant, he often answered, "You don't want to know."

But in the end, after two years of Operation Cherokee, when cops swept up more than a dozen suspects on racketeering and related charges across South Florida, Sonken wasn't among them. The cops raked in members of the Gambino, Genovese, Maggadino, and Bufalino families. Green wrote in his report that there was "an air of sadness... a feeling of doom" in the mob. The big-ticket target of Operation Cherokee, billed as the most sweeping sting of organized crime in state history, was Anthony "Guv" Guarnieri, an unwell older man who died weeks after being convicted. Guv had been shocked and hurt when Green showed up at his door with a badge, though Guv later said he understood the cop was just doing his job.

Green's boss, Steve Bertucelli, projected a clear message about Gold Coast: "We can follow the mob wherever they move." But from the perspective of many in law enforcement, Gold Coast presented a rare prize — a single location to observe and keep track of underworld figures. If investigators kept their distance, the mob, out of habit and complacency, would continue to serve up valuable intelligence.

Whatever one might think of Sonken's tolerance of shady figures, the widespread presence of the Mafia in South Florida included far bigger enablers than a waterfront restaurant filled with Chicago kitsch. Intermittent regimes of corrupt or permissive sheriffs and other officials propped up organized crime. Police departments and federal agencies often clashed and competed instead of coordinating. There were showboats who nabbed low-level hoods instead of patiently building cases to compromise higher echelons. On top of it all, popular culture glamorized organized crime, jumbling reality and the spectacle of the mob.

No wonder when actor John Marley, who played the movie executive who wakes to a horse head in his bed in The Godfather, ate at Gold Coast in 1975, he was surrounded by diners asking, Was that horse's head real?

I became interested in the lost Gold Coast legends while attending high school in the Joe Sonken Building at University School beginning in 1988. The pale stucco structure boasted an oversize red-tile turret outside and bright-blue lockers. The name "Sonken," spelled out in silver letters that glinted in the sun, didn't mean much to me. I remember hearing he owned a restaurant with good stone crabs. Only later, when I could address my former teachers by their first names, did I learn that many on the faculty had found the combination of a high school and a Mafia friend a head-scratcher.

When I began canvassing people about Sonken, I was stunned to find that my older brother Ian had known him. Ian was born with spinal muscular atrophy, a degenerative neuromuscular disorder. From age 6, he was confined to a wheelchair, and doctors predicted a short lifespan. But he was not one to surrender. He was, as we always understood it, the first wheelchair-bound student to be mainstreamed into a public elementary school in Davie — at Davie Elementary, which he attended from 1980 to 1983. He served as lieutenant on the student safety patrol, zooming around in his motorized wheelchair, wearing a neon-orange belt and metal badge, and shouting at stunned parents who idled in their cars too long. In 1983, Ian switched to the same private school I attended, Nova's University School, for sixth grade.

People often show discomfort around children with disabilities. They look at them too long or not at all. "I've accepted the fact that I am handicapped," Ian said at the time. "I don't see why they can't." He had his defenders, like his beefy friend Eric, who directed a visceral growl at anyone who gawked at Ian at the mall or multiplex. Ian's thousand-watt smile put everyone at ease, and he enjoyed attention. He spoke a mile a minute, sometimes having to be reminded to let people respond. A fearless extrovert, Ian even struck up a long-distance friendship with Michael Landon, the legendary actor of Little House on the Prairie and Bonanza fame. He hooked Landon on an idea for a sitcom about a wheelchair-bound teen. (Landon and Ian discussed it several times before the actor fell ill with the pancreatic cancer that took his life in 1991.) At Ian's bar mitzvah, guests were greeted by a sign-in board with a caricature of Ian posed as Mad Magazine mascot Alfred E. Neuman, complete with the caption "What, me worry?"

As a middle schooler in the mid-'80s, Ian met up with his best friend Ben at Gold Coast. Ben, who asked that New Times not use his last name, worked at Gold Coast as a busboy and later a valet. The whir of Ian's wheelchair announced his presence amid the stings and stakeouts. Ian remembers that during his first visit to Gold Coast, the tall, tuxedoed maitre'd, Joe Ciro, approached. He leaned his salt-and-peppered head down and half-whispered, "Joe wants to see you."

Bozo, the best known of Sonken's English bulldogs, chewed on the bumper of Ian's wheelchair. (One cook even laced his pants with Tabasco sauce and pepper to deter Bozo's bite.) Ian rolled over to Sonken's table but almost turned around to go. "Sonken asked what was wrong," Ian remembers. "I said, 'I'm sorry, I can't be around people smoking.' He put out his cigar right away."

They chatted while Bozo slurped up a bowl of pasta on Sonken's table. This became a routine when Ian came to the restaurant. Ian recalls that Sonken spoke in a rough, deep voice and always remembered his name. "He didn't talk much," Ian says. "He would ask me how I was doing."

Ian would take it from there. One conversation Ian recalled jumped out at me.

"Where will you go to high school?" Sonken asked, waving his unlit Gold Coast-branded cigar.

"University School," Ian said. But this was 1985, and students used classrooms in Nova's Parker Building, a tightly packed concrete bunker. "We don't have a building for high school," Ian explained.

"That's a shame, kid. Everyone deserves a high school."

By this point, Sonken was already discussing a donation to Nova. At first, though, the plan was to help fund a $2 million gymnasium for the college. At some point, perhaps remembering his talk with Ian, the restaurateur redirected his gift to the high school. "If I'm going to give it," Sonken told the Miami Herald, "I want to give to somebody I thought was worthwhile."

No one knows whether Sonken's motivation for dedicating $375,000 (worth almost $850,000 today) to building our high school involved Ian. But no one I interviewed was surprised to hear about his kindness to Ian. "That's typical," Sonken's accountant and confidant, Mike Zier, says of his former boss. "He loved children and animals."

Ian relished hearing insider stories about Gold Coast, including the time Sonken slipped Ian's friend Ben $50 to go to a woman's backyard in Hollywood and dig a shallow grave — for a distraught neighbor's dog.

Ian recalls being shocked when he heard Sonken was at the wheel when his Oldsmobile rolled into the Intracoastal late one night in May 1986. "I remember Ben calling and saying, 'Someone tried to kill Joe.'" The Herald rushed out the news in the morning edition: Sonken and the two basset hounds with him, Tillie and Amos, had drowned when the car plunged backward into the water behind the restaurant, the newspaper reported.

It was the end of an era. Except it wasn't. Sonken hadn't drowned, though he came close. The Gold Coast regular who heard the commotion, speedboat racer Ben Kramer, dove into the 20-foot-deep water after him. Along with bartender Paul Verdi, who also waded into the Intracoastal, Kramer pulled Sonken out through the car window. In a flash, the Oldsmobile was gone. Sonken had waited as long as he could before escaping the car to try to save the dogs. The Herald was also wrong about one of the dogs. Sonken rescued Tillie. Amos was lost.

Kramer later recounted his tale to his probation officer, Rory McMahon, who's now a private detective in South Florida. "Some fucking hero you are," Sonken said to Kramer once they had all reached dry land. "Couldn't even save the dog."

If I had known that would be the response, Kramer thought to himself, I would have let the old man drown.

The Herald's initial error repeated a pattern in Sonken's life. What seemed cut-and-dried was anything but. (Kramer, honored by a state legislator as a hero, would be convicted of planning a brazen murder that took place months after Sonken's accident. He later tried to escape a South Dade prison by helicopter.)

Police found no evidence of tampering with Sonken's car. "We never heard of any beefs anyone had with Sonken," says Douglas Haas, former director of an organized crime task force for South Florida. "He was well respected." Far likelier was that an older man had too many drinks by the end of a long day. One hazard of being Joe Sonken was that people constantly bought him liquor, leading to a directive to the bartenders to fill his glass with ginger ale or watered-down booze. Sonken also faced mounting pressures. His stamina wasn't what it had been, and the quality of the restaurant began to decline.

The mystique of Gold Coast never went away and still provides fertile ground for the imagination. There were rumors of secret passageways in the building. And several former associates of Sonken's told me there were things they couldn't disclose. At least one of the cooks came to work armed with a gun, serving a secondary role as a bodyguard, a former busboy told me.

Sonken died June 2, 1990, at age 83 of kidney failure — almost four years to the day after the Herald had reported him dead. His dogs were taken in by various friends. Tillie, who also cheated death in the car accident, went on to live a happy life on a farm. Sonken had a girlfriend, Annie, but never married or had children.

After his death, he made sure his longtime housekeeper, Mary Courtemanche, received a substantial sum. Cones marked his parking spot along with a sign: "Don't even think of parking here. Joe Sonken's only." Another sign by the front door read, "Poor old Joe."

Comparing reputation and reality in the world of Sonken leads to what might be the biggest twist of all in a life full of them: He was a remarkable philanthropist. The donation to the University School — a turning point for a scrappy up-and-coming school to become what is now a widely respected program that anchors a section of Nova's campus with the Miami Dolphins practice field — represents just the beginning of that legacy.

Cones marked his parking spot along with a sign: "Don't even think of parking here. Joe Sonken's only."

tweet this

In his final years, he set up the Sonken Charitable Trust. Beginning with the sale of the Gold Coast property in the mid-'90s, the trust has donated more than $2 million to charities. The local chapter of the Association of Fundraising Professionals honored the Sonken Charitable Trust as the area's "outstanding foundation" in 2001. The trust, which receives scores of requests, grants money to help animals and children with disabilities or special needs — the restaurant owner's quiet passions.

Results from these donations have included a unique playground for children with disabilities at the David Posnack Jewish Community Center in Davie and veterinary care for retired racing greyhounds at Hollydogs in Hollywood. The trust has also funded Christmas dinners for the homeless held by the Hollywood Police Athletic League and facilitated a mobile health-care program cofinanced by the Dade County Chiefs of Police Association. In light of Sonken's reputation, this generosity seems about as likely as a Jewish kid from hardscrabble Chicago, born to Eastern European immigrants, serving Italian food "as good as any... in Rome" (as syndicated columnist Jim Bishop judged it in 1971) in former Florida marshlands.

On a brisk Saturday morning this past December, a line of cars spills out the right turn lane from A1A in Hollywood, idling for the next valet in front of GG's Waterfront Bar & Grill, a gleaming restaurant that advertises a "chef-centric, high-energy concept." Lush foliage clings to the exterior wall, while the sparkling Intracoastal beyond is dotted with pleasure boats.

Sonken's inner circle kept Gold Coast open after he died, even brought back live music, but its foothold in the dining landscape wobbled in an era of Chili's and Olive Garden. The heart of the restaurant was gone. And the strip of A1A nearby hit hard times after the Diplomat Resort closed in 1991 (and didn't reopen until 2002). Even Dave Green of the Broward Sheriff's Office, Sonken's version of Inspector Javert, lamented after visiting at the time: "It's not nearly what it was."

Over the course of its 38 years under Sonken, Gold Coast went through only three primary chefs and maitre'd's. People who worked with Sonken were fiercely loyal. Former employee Rip Ortega, who went on to own restaurants and now works in food-service distribution, calls his time at Gold Coast "the best education you could ever want to have." Sonken gave his friend and accountant, Mike Zier, an apartment in the upper part of a building adjacent to Gold Coast that now holds Giorgio's Bakery. Zier calls his time working with Sonken "the happiest years of my life."

Then there were the mobsters who gravitated to Gold Coast for business and leisure. Sightings of the understated Meyer Lansky at Gold Coast were replaced with 1980s Mafia leaders such as the flashy John Gotti and old men with bad face-lifts to conceal their identities. Local murders connected to organized crime piled up headlines. "There were no more gentlemen's agreements" around South Florida, NSU law professor Bob Jarvis explains, "because there were no more gentlemen." The traditional mob fell into decline, pressured by drug traders who didn't follow any playbook. Gold Coast closed for good in May 1994, when Miami Subs founder Gus Boulis purchased the property. (Coincidentally, Boulis would later be gunned down over a business deal, an execution-style murder arranged by Gotti's Gambino crime family.)

In 1997, Giorgio's Grill, a Greek eatery, opened on the Gold Coast property. The space was thoroughly renovated and updated. The old cherry-wood panels were replaced with cream-colored walls made to look old. The restaurant flourished for a dozen years before giving way to the equally well-received GG's.

When I called GG's in December to ask about the legacy of Gold Coast, Dan Serafini, a co-owner with his wife Lise-Anne, explained he has "moved on" from the site's Mafia-tinged past. Serafini offered to give me a tour if I came by. But then he stopped returning my calls, and just weeks after we first spoke, a reference on GG's website to bygone days with "infamous characters like mobster Meyer Lansky" was removed. Perhaps the timing was coincidental, or maybe we all carry instincts to pave over the complicated, the mysterious, the warts-and-all history to protect a shiny, spotless gold coast.

Indeed, few if any of today's guests know their table was once photographed by long-lens cameras a mile out at sea and bugged by an undercover agent at the next table. All they see to connect the place to the past is a sign outside the entrance that would have galled Joe Sonken: "No Cigar Smoking. Thank You!"

Ian, now 46, suffered medical setbacks around the time of Sonken's death, shortly after completing high school in the Sonken Building in 1990. He recalls the elevator specially designed to meet the dimensions of his wheelchair. Since then, Ian has been on a mechanical ventilator that helps him breathe. He remains fearless. "Ian's Law," a legislative act passed in New York in 2010 to protect patients with severe medical conditions from losing insurance, was named for his public advocacy.

Toggling his wheelchair back and forth, Ian perks up while remembering rolling up to Sonken's table at the old man's invitation, in view of the whole restaurant. "He always smiled when he saw me."

© Matthew Pearl, all rights reserved. Pearl, who grew up in South Florida, is a New York Times best-selling author of six novels that have been translated into 30 languages.