Lost and Found

(Atlantic/Rhino)

They're a select group, a handful of singers that can pull up emotion and hurt so palpable that it's almost painful to listen to, but you want to listen anyway: Billie Holiday, Neil Young, Otis Redding, come immediately to mind. Add to their number an overlooked crooner named Jimmy Scott.

As in Little Jimmy Scott, the quirky R&B singer of the Fifties, who's best known for his sweet, otherworldly falsetto on such tunes as "A Rage in Harlem" (featured in the Eddie Murphy flick of the same name), and more recently for lending a surreal majesty to Lou Reed's stunning "Power and Glory" from the album Magic and Loss. Turns out that Scott is also a remarkable jazz singer as ably displayed on Lost and Found, sides recorded in the late Sixties but never released due to label wranglings and the misplacement of the master tapes (a liner note from the album producer, who found them buried beneath a pile in his garage, warns what happens when you don't just say no). Had the tapes been released back then, they very well may have rocked the jazz world. Or they may have been dismissed by audiences seeking the electric noodlings so popular at the time. The renaissance of traditional jazz and the re-emergence of lush balladry, however, make Lost a very timely release for the Nineties.

In fact, lush doesn't begin to describe the songs collected here. Scott is totally unhurried, floating his vocalese atop subdued and gorgeous settings provided by a stellar group of jazz veterans. The phrasing of the balladeer is unique, emulating the patterns of Miles Davis or Coleman Hawkins at their most languorous. Every word, every phrase is sung for maximum visceral impact, never over the top, but always sounding on the verge of breakdown. Popular standards such as a slow and lovely "For Once in My Life" and a heartbreaking version of "Unchained Melody" are mixed with some obscure gems, such as the poignant "Folks Who Live on the Hill," which wouldn't have sounded out of place on one of Dexter Gordon's quieter albums, and features resonant bass notes and light brush drumming.

Jimmy Scott is a true original; he doesn't really sound like anyone (maybe if Smokey Robinson cut some jazz sides...). Some may be troubled upon hearing a voice that's vague genderwise A he's no Joe Williams A but the emotions engendered here are universal enough to make even the stoniest listener put chin in hand and heave a sigh.

-- Bob Weinberg

American Music Club

Mercury

(Reprise)

The monkey went wild on-stage, singing love songs. Then gratitude walks into the CD player and the piano plays. That's the kind of thing that happens here.

Trapped in a room on Sixth Street. Slapping a laughing face that's drunk on applause. Time passes like a joy. Maybe I'm almost there.

Turn me into another Great American Zombie. Curse the sky. Please don't bring me back. Your beauty is just a slap in the face. Forget Hollywood.

What Godzilla said to God when his name wasn't found in the Book of Life. What can come around 52 secrets. The slide guitar whorls.

So far down A like an ant on your map. Listen to the sound the air makes when you fall. The bass booms.

Hanging by a thread, blown around like sand. Give me a place to stand. Give me a body bag and a dangerous, empty life. What this world needs me for but an apology for an accident. Mr. Ed eating his way in hay, too weak for my taste. The toms beat.

Learn how to disappear in the silk and in the spotlight. He sings like a thief.

A scarecrow looking for a barn fire to sleep on. All of heaven's 10,000 whores afraid to leave me breathing. Hide somewhere. Take a left. Or a right.

Will you find this? You must find this.

-- Rat Bastard Falestra

Dr. Dre

The Chronic

(Interscope)

Those bluntin' bad boys from Cypress Hill have swung wide the door for weed-friendly art, and while some might say it's about time the 'erb came out of the smoke-filled closet, others are already backlashing against buds. Not N.W.A. grad Dr. Dre. The inset of his latest boldly boasts a reefer-leaf image over which the song titles are printed. Welcome to the bandwagon, Doc.

Dre even goes so far as to pay respect to the demon weed in "The Roach." Unfortunately, aside from that puff piece, Dre seems content to rehash (ahem) the same old gangsta topics he and his N.W.A. homeys first made popular. In fact, this record's brightest spot comes courtesy of guest vocalist Snoop, who you've probably heard on the album's hit single, "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang."

Anyway, The Chronic goes far in its efforts to prove Dr. Dre hasn't lost his way with hard-ass, pumpin', gangsta gang-bangin' tunes. Nonetheless, I still prefer his work with N.W.A. United we stand, divided we fall.

-- Joey Seeman

John Campbell

Howlin' Mercy

(Elektra)

Beneath the bandages, John Campbell was scarred, the victim of a disfiguring car accident. To get him through this rough period of convalescence, the adolescent Campbell listened to the blues, drawing strength from the raw emotion and pain expressed by artists such as Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker, guys who knew a thing or two about suffering. "The blues is a healer," sang Hooker, and in a cathartic way it was for Campbell, whose scars went far deeper than the skin.

For years New York club denizens knew what the rest of the blues world is beginning to find out: John Campbell is one of the most startling and passionate blues players around. His debut on Elektra Records, One Believer, featured urban nightmares such as "Tiny Coffin," about the littlest victim of a drive-by, and Robert Johnson-inspired creepshows such as "Devil in My Closet," as haunted and haunting as the original bedeviled bluesman. Campbell's follow-up, Howlin' Mercy, continues in that vein A raw-nerve vocals drenched in whisky and coated with gravel and, perhaps even more effective, stinging, expressive slide and fiery fret-shredding.

Although he pays tribute to the Delta bluesmen of old on tunes such as "When the Levee Breaks" and "Saddle My Pony," Campbell's scathing string scorch is equally informed by aggressive, balls-to-the-wall rock and roll. (It's fitting that he lists both Memphis Minnie and Jimmy Page/Robert Plant as the authors of "Levee".) Campbell fuses traditional forms into a style of his own making, coupling unique guitar lines with a distinctive voice (though he's barely distinguishable from Tom Waits on "In the Hole," an outstanding track contributed by the boozy-voiced barroom poet). Also like latter-day Waits, Campbell's tunes possess an apocalyptic power fueled by percussive assault A be glad the drummer decided to take his hostility out on the skins, rather than on mankind.

But there are lighter moments on Howlin'. The autobiographical "Look What Love Can Do" has the hellish rakehell "tossing his black book to a stranger," giving up his hobo rail-ridin' ways for the woman who has transformed him. Although still touring feverishly, Campbell is now relatively settled with wife and child, effectively slaying some of the demons. But don't think for a moment the lanky guitar-skinner has gone soft. One listen to Howlin', with its rattlesnake-tail-and-coyote-bones percussion (no kidding), is enough to have you checking your closet before turning out the lights.

-- Bob Weinberg

Daniel Lanois

For the Beauty of Wynona

(Warner Bros.)

Known for his brooding aural energy and ever-present reverb, French-Canadian producer Daniel Lanois became one of the hottest names of the Eighties for his work with U2 and Peter Gabriel, and his top-secret mix of layering and lushness also sculpted efforts by the Neville Brothers, Harold Budd, Robbie Robertson, and Bob Dylan. In 1989 Lanois decided to perform his own material, and his debut LP, Acadie, was a natural extension of his production jobs A subtle, roots-'n'-blues compositions steaming like a bayou morning.

For his sophomore effort, For the Beauty of Wynona, Lanois has tinkered slightly with the formula that made him, supplementing his own guitar and keyboard work with the New Orleans rhythm section of bassist/vocalist Darryl Johnson and drummer Ronald Jones. While the Crescent City battery provides a sturdy spine and the occasional spark of live-in-the-studio fire, the result is mostly pure Lanois. From the opening track, "The Messenger," Wynona (not Ryder, incidentally A she spells it with an "i" A but a small Canadian hamlet) rocks with a mythic mid-tempo grace, insinuating a hypnotic intimacy. When the Lanois sound succeeds, when the hazy blues licks and the rolling percussion lock into their groove, the result is stunning A an ear-candy Tootsie Pop with a roots center.

The problem with Lanois, of course, is that superb production can elevate less-than-superb material A as eloquent as Lanois's sound becomes, his songs sometimes border on the boring. The Gabrielesque "Still Learning How to Crawl," for instance, creeps along like the muddier work from Gabriel's recent Us, as does the precious bilingual love song "The Collection of Marie Claire." The beautifully engineered "Death of a Train" is nearly anesthetic (can anyone say Cowboy Junkies?). Sometimes, as on the short instrumental "Waiting," Lanois seems merely to be flexing. While eminently listenable, atmospheric groove exercises aren't exactly kinetic. Which isn't to say that Wynona sleepwalks. The hypnotic Afrobeats and edge-of-menace vocals in "Beatrice," for instance, overcome murky lyrics, as does the tribal rhythm kill of "Indian Red." And "The Unbreakable Chain" locks into an unbreakable melody.

For all the promise of his production, Lanois shines brightest as a songwriter when he strips his sound bare, as two remarkable compositions near the album's end attest. "Sleeping in the Devil's Bed," which first appeared in Wim Wenders's Until the End of the World, is a sturdy folk-country number underpinned by light brush percussion, and its loping piano and smooth retro vocals generate surprising power. With simple but evocative lyrics ("I think of you when I tell myself/And the fever rises high/I think of you and I get what's coming/Sleeping in the devil's bed"), the song sounds like a missing gem from the Band's past, a distant cousin of both Bob Dylan's "Man in the Long Black Coat" (which Lanois produced) and Skip James's "Devil Got My Woman" (which he didn't).

After an uncharacteristic burst of eruptive, rubbery fretwork on the title song, Lanois returns to simplicity with the album's masterful closer, the frangible "Rocky World." Galvanized by a strong storytelling ethic and eloquent imagery ("I'll tell you there's something I'll never forget/The sight of you in silhouette"), "Rocky World" renders a series of piercing small-town portraits with poetic economy. And just as the mix swells behind a religious metaphor and a ponderous coda seems imminent, Lanois dissolves his song, and his album, leaving behind only the fragrance of a strummed string.

-- Ben Greenman

David Coverdale and Jimmy Page

Coverdale/Page

(Geffen)

Some of this sounds a lot like David Coverdale auditioning for a singing job with Demonomacy. Give him Brownie points for ambition. And Page? Sounds a lot like Jimmy Page, minus the adventurous songwriting and pure panache of Led Zep. Power chording and growly vocals (even with the requisite ballad and a nod or two to the blues) plus lots of superficial hookiness and an obvious theme of "we want a hit" do not a great rock record make.

It's a safe bet Mr. Whitesnake and Mr. Satan had some fun recording this new album, cutting tracks in Vancouver; Abbey Road in London; Hook City, Nevada; and Miami's Criteria. Too bad listening is not much fun. A great rock record Coverdale and Page did not make.

-- Greg Baker

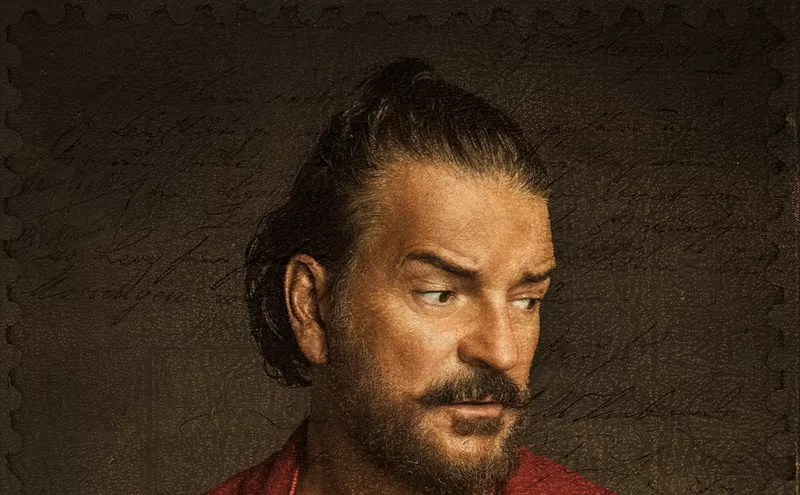

Nick Scotti

Nick Scotti

(Warner Bros.)

From the tip of his I'm-terse-I'm-fashionable moniker to the tail of his first (and hopefully last) LP, Nick Scotti reeks of the most abysmal sort of pretty-boy folderol. Press material for this Madonna-discovered model-turned-singer (where are the border guards when you need them?) drones on and on about "an impressive roster of musical influences" and "superstar showcase," but the fact of the matter is that it took five production teams and a half dozen songwriters (including Patti Austin, Maxi Priest, Diane Warren, and the Material girl herself) to float ten songs, and that the results are exactly what you'd expect A anemic dance-soul with plenty of padding and the occasional lucky strike (the faux fatback bass carpeting "Slow Down," for instance, or the churchy synths of "Just No Justice"). Scotti has a sizable voice, but his delivery is all pose, nothing that Rick Astley couldn't knock off on his way to has-been rehab, and the flat stab at the Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes chestnut "Wake Up Everybody" is about four cents short of a nickel.

To misquote Casey Stengel, talent isn't everything, it's the only thing. Beefcake for boneheads.

-- Ben Greenman

Various Artists

The Beat Generation

(Rhino Word Beat)

For all those whose lives were changed by reading On the Road, this box is for you. And of course the author behind that well-thumbed Beat bible is well-represented, opening Rhino's exhaustive three-disc compilation with a reading that captures the mood and excitement of the movement more than just about anything that follows.

Rhino's approach, although extensive, is too catholic; mixed in with the excellent readings by Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Ken Nordine are dated "novelties" by the likes of Edd "Kookie" Byrnes ("Man, dig this crazy pad!") and yes, even Perry Como, attempting to cash in on the Beat tip. That said, Beat Generation truly is a fascinating look at a subculture that at least produced as much good art as it did cheap rip-offs by bogus Bohemians.

Sure, there's plenty of breast beating and raging against the staid social mores of the Eisenhower era. But what's really interesting is the sense of the sublime the Beats often found in the mundane and absurd, whether in the nonsensical and oh-so-cool lyrics and delivery of Slim Gaillard ("Yip Roc Heresy" is just plain hilarious) or the pleasures of a midnight snack as detailed by jazz poet Ken Nordine. Gaillard and Dizzy Gillespie, who contributes a breathless scat that mimics his remarkable be-bop horn phrasings, represent the roots of both Beat lingo and attitude. They in turn learned from the master of cool, tenor man Lester Young, whose verbiage was so esoteric he practically had his own language. Kerouac's worship of black society, particularly the jazz and blues underground, is fawning to the point of obsequiousness, but there is no question that he found a vitality among blacks sorely missing in repressed white Fifties America. Perhaps we have him to thank for Vanilla Ice.

What Generation needed was a good editor. What's mildly amusing in Babs Gonzales's drug-culture, lingo-laden "Manhattan Fable" makes redundant the later readings of "Rumpelstiltskin" and "Christopher Columbus" that mine similar territories for cheap laughs (i.e., Rump and Chris as beatniks). A long, rambling (mostly pointless) interview with Kerouac by Ben Hecht and long, rambling (but educational) documentaries by veteran newsmen such as Howard K. Smith and Charles Kurault grow tiresome. On the plus side, the jazz tracks are cool in the best sense of the word, and quirky (Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross's "Twisted" is pure nervous paranoia), illustrating the aesthetic of movement and restlessness that the Beats embraced. Although there's plenty to recommend on Generation, it is box sets like this that make "shuffle-play" on the disc player such an attractive option. To paraphrase one of the most Beat characters of all times, Bullwinkle J. Moose: Sometimes a beatnik is just a bum in sunglasses.

-- Bob Weinberg