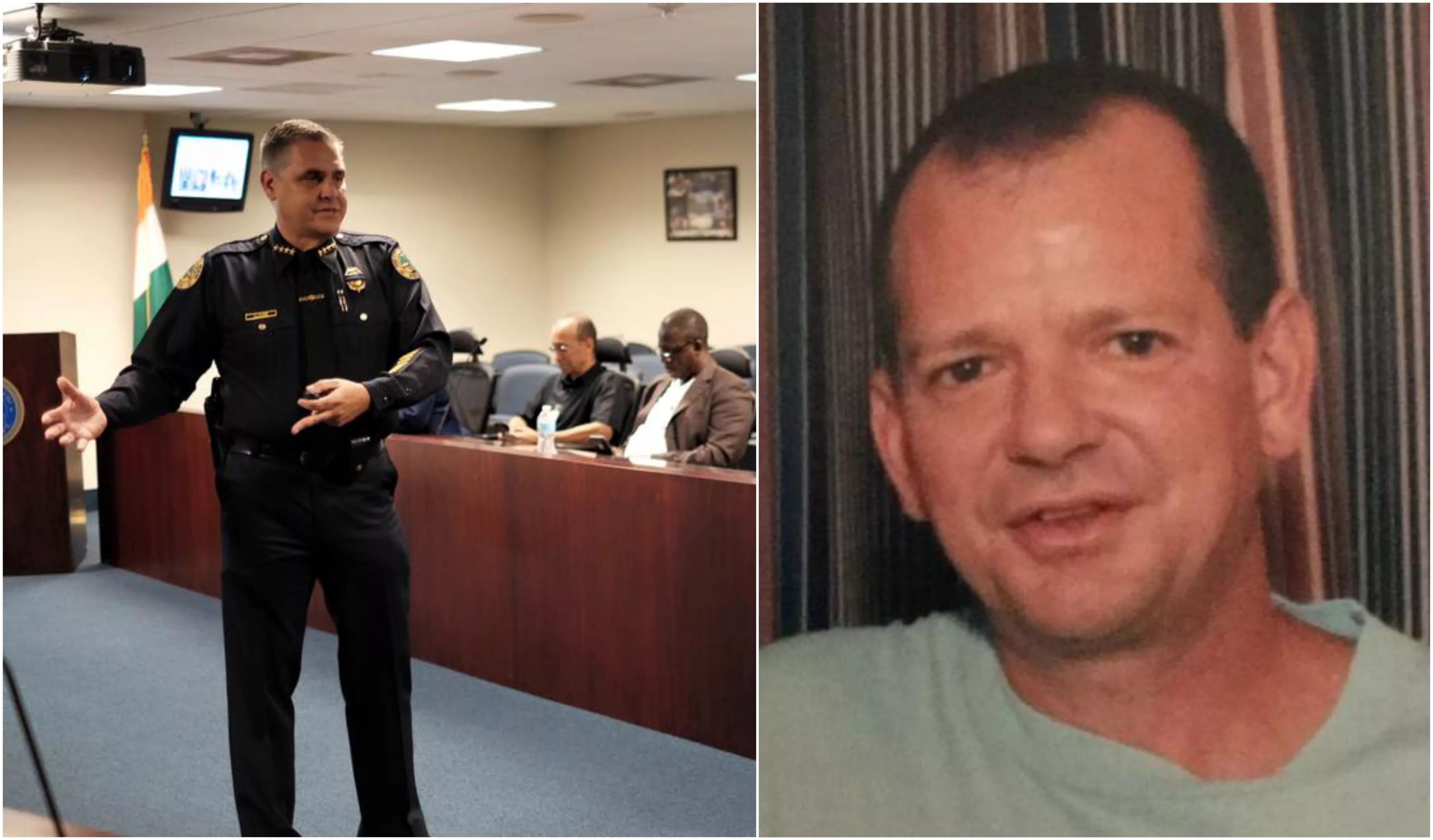

photos courtesy of Miami Police Department, Kathy Kavalin

Audio By Carbonatix

Last June, as William “Pete” Owen was about to be terminated from the Miami-Dade Water and Sewer Department, the county called his relatives to give them a headsup.

His siblings immediately became worried: Owen had held the same job for more than 30 years, and it remained one of the few constants in his life as he grew ill and struggled with depression in recent years. That same day, his family contacted Miami Police to request a welfare check on the 59-year-old. Officers found his apartment empty but saw no signs of foul play.

What the family didn’t know is that Owen had already been dead – with his body lying in the county medical examiner’s office – for seven days by the time they had called the cops. Despite the fact that officers had recovered Owen’s body from beneath a Metrorail overpass May 31, his sister Kathy Kavalin says, Miami Police never notified relatives to let them know.

“It’s really messed up,” says Kavalin, who lives in Orlando. “It was very devastating.”

The situation is unfortunately all too common in South Florida. In recent weeks, New Times has reported on at least three instances where police failed to notify next of kin of a loved one’s death. The family of an elderly Hallandale Beach woman is suing the city after police failed to call anyone and then cremated the body without consent. And relatives of a missing Miami Shores man have demanded answers from Fort Lauderdale Police, who found the man’s body but never contacted them.

In Owen’s case, Kavalin says she called at least 15 hospitals and four nursing facilities in search of her brother in the days after he went missing. Over the years, he had suffered from debilitating arthritis in his knees and developed a dependence on oxycodone. Kavalin says her brother became depressed and withdrawn from life, becoming somewhat of a hermit, though he was able to keep his job with the county.

On June 7, Kavalin called police to report Owen missing, but she was told she had to make a report in person. Because she lives four hours away, a brother drove down from Broward County but was left waiting for three hours before an officer finally took down Owen’s name and asked if he had any tattoos. Kavalin says the officer never asked for additional identifying information such as date of birth or a photo and failed to cross-reference his name in the county’s database of deceased persons.

“Had she put the right information into the computer… that would have stopped everything in its tracks,” Kavalin says of the officer. “That would have been a couple days less of worry and torment trying to find him.”

Discouraged that police weren’t motivated to solve the disappearance, Kavalin says she searched her brother’s name on the medical examiner’s website but got no results. Exasperated, she finally called the medical examiner’s office June 9 – ten days after police found her brother dead. It was only then she learned that her brother had been in the county morgue the whole time. (She was later told she had entered too much information in the database – because of the way the database is configured, it’s apparently better to enter data in only one field, such as last name.)

Miami Police have released few details about the case, claiming the investigation is still open despite the fact that Kavalin says her brother’s death was a cut-and-dried case of suicide. In an email to New Times, spokesman Officer Michael Vega declined to provide an explanation for the department’s failure to contact next of kin.

“At this time the investigation is underway; therefore, all pertinent information will be disseminated as soon as it becomes readily available,” Vega wrote.

For Owen’s family, many questions still remain. When Kavalin finally got ahold of the medical examiner’s office, she says, the paperwork indicated that Owen’s landlord, Gabriel Lopez, told police Owen had no next of kin. But Kavalin says Lopez isn’t actually her brother’s landlord – he just lives at an address almost identical to her brother’s. Lopez lives at a home on SW 26th Street, while Owen rented a home on SW 26th Terrace.

Kavalin now believes police falsified the supposed conversation with Lopez in an attempt to close out their report on her brother. Reached by New Times, Lopez says he never received a call from Miami Police in reference to Owen or any other missing person’s case or death investigation.

“Not that I remember,” Lopez says.

Kavalin has detailed her complaint in a letter she sent to Miami Police, the medical examiner’s office, and county commissioners in mid-January. But to date, she says, she has yet to receive an apology.

“We’re extremely frustrated,” she says. “There was just so much incompetence.”