NOAA / Satellite and Information Service

Audio By Carbonatix

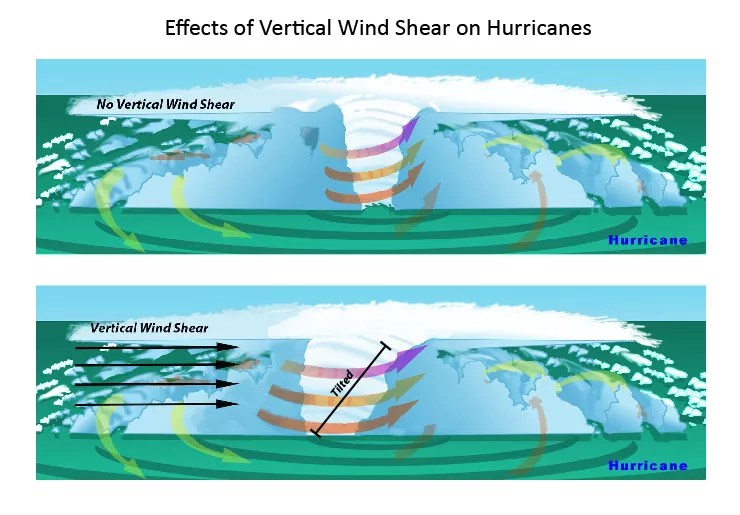

If you live in, say, Maine or Oregon, you likely don’t spend a ton of time thinking about the meteorological concept of wind shear. But for Floridians, the concept becomes immediately important from June 1 through November 30 every year. In layman’s terms, strong vertical wind shear – that is, a strong difference in wind speeds at various heights in the atmosphere – chops up hurricanes and makes it more difficult for them to form. In a postmortem recap, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) said Hurricane Irma in 2017 “strengthened rapidly in environmental conditions of low vertical wind shear,” among other conditions.

Well, a new study has some good news for hurricane chasers and bad news for basically everyone else who lives in a storm zone: Researchers from NOAA and Columbia University released a study at the end of last month warning that climate change will likely weaken overall wind shear along the East Coast.

“Our results emphasize the potential threat that hurricanes may become more intense in the future as they move toward the East Coast of the United States,” the study warns.

According to the paper, which was published May 24 in Nature‘s peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, a strong wind shear acts as a barrier between the States and many hurricanes that form in the Atlantic Ocean. But greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere are likely to weaken this natural wall – some models predict Americans could begin to see the effects by 2050. (The study notes the effects will not be as pronounced on the Gulf Coast.)

Wind-shear models from the NOAA

illustration by NOAA

Climate scientists for years have debated the ways in which human-caused climate change could impact hurricanes. Though climate change is not the sole cause of hurricanes, climate scientists uniformly agree that warming temperatures will increase the frequency and intensity of storms. (Hurricanes need warm ocean water to form, and climate change will provide more hot water over the years.) Last year, researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory warned that climate change will likely increase hurricane rainfall by an average of one-third and increase wind speeds by 25 knots if humans don’t cut their carbon habits. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2017 stated “there is observational evidence for an increase in intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic since about 1970, correlated with increases of tropical sea-surface temperatures.”

Apparently, folks living on the East Coast also now need to worry about losing the wind-shear belt that’s protected them for the past few decades. Seasonal wind shear has killed many a potential storm over the years – hurricanes have regularly approached Florida and the Caribbean from the central Atlantic, only to run into what is basically a wind-shear wall off the U.S. coast. But some storms still get through: NOAA researcher Neal Dorst told the Miami Herald in 2017 that low vertical wind shear was one of the biggest reasons Hurricane Irma was able to slam into Florida.

This latest study, however, shows weak wind shear itself could also be a manifestation of climate change.

“The weak vertical wind shear environment would help hurricanes reach their potential intensity, the maximum possible intensity given the environmental conditions, which has already increased in magnitude due to warmer sea surface temperatures,” the researchers warn.