Illustration by Jesse Lenz

Audio By Carbonatix

The three kids heard something in the night but figured mom was just arguing with her boyfriend Carlos. So they went back to sleep. Friday morning, 8-year-old Noah got up for school and awoke his siblings, 4-year-old Martha and 3-year-old Michael. Mom and Carlos still hadn’t stirred, so he walked into their bedroom.

Then he saw them.

What to do? He didn’t know. He touched the blood to make sure it was real. For a few hours, he and the others sat near the bed and sobbed. Their pit bull puppy wandered around, tracking tiny red paw prints through the house. Finally, Noah and his sister grabbed a sheet of paper and some crayons. They drew two headstones, both cross-shaped. On the bottom, they scrawled, “Rest in Peace, Mom and Carlos.”

Rain poured on Key Largo. The water sluiced down Cuba Road, a sleepy block that dead-ends into Dove Sound, a mangrove-shaded inlet connected by canal to the Atlantic Ocean a few blocks away. Eventually, Noah made a decision: They’d have to find somewhere else to live. He grabbed his siblings, and they started walking up the sodden street.

Travis Kvadus, their next-door neighbor, rolled over in bed and checked the live feeds from the cameras he’d mounted in front of his house. The 33-year-old fisherman rubbed his eyes, confused. Why were the three kids he regularly babysat walking around in the rain?

He jogged out and opened the gate. The children rushed into his gravel-strewn front yard. “Mom and Carlos are dead,” Noah told Kvadus.

“Are you sure?” he asked, still trying to wake up. “They’re not just sleeping?”

“There was blood,” Noah said.

Kvadus was silent for a moment. “Well,” he said, “you’d better show me.”

Inside the bedroom, the bodies were splayed across the floor. Tara Rosado, a strikingly pretty 26-year-old with aqua-blue eyes, lay flat on her back, her arms stretched straight out to either side. Carlos Ortiz – muscular, with a buzzcut, and four years older – slumped with his torso hunched awkwardly over his legs. Both had been shot through the head. Dark, nearly black blood soaked the floor near a pile of plush kids’ toys.

Kvadus, a certified boat captain, had some first-aid training. So he reached to check for a pulse. But then he looked again at those gunshot wounds. His neighbors were plainly dead.

“You spend enough time out there, you’ll find drugs every five years or so.”

The Florida Keys are many things: a sun-bleached playground for the ultrarich, a blue-collar home to thousands of fishermen and hospitality workers, a rural chain of coral rock emerging just above the rising seas. There are ugly bar fights and plenty of drugs. But there’s hardly any gun violence. A young couple brutally executed a few feet from their young children? Never.

Rosado and Ortiz’s mysterious killing on October 15, 2015, sent locals from Key Largo to Islamorada into a panic and left sheriff’s deputies scrambling. Detectives would follow a trail of violence and blackmail for months before divining its source: Jeremy Macauley, a fisherman with a troubled past who’d found a bale of pure cocaine floating in the turquoise sea. Months later, a prosecutor’s suicide and a surprise jailhouse interview would further muddy the tale.

The untold story of Key Largo’s most brutal homicide in 25 years shines a light on a drugged-out Upper Keys underbelly worthy of a Bloodlines subplot and reveals a surprising truth: Every year, dozens of Florida fishermen find square groupers – packages of marijuana or cocaine, sometimes worth millions of dollars – drifting in the ocean. Then they have to choose: Call the Coast Guard? Or chase the promise of riches far beyond what a fishing boat can provide, risking prison time – or, in some cases, unimaginable bloodshed.

Rosado’s home in Tavernier.

Photo by Tim Elfrink

Thomas Breeding was reeling in grouper about 50 miles south of Panama City when he spotted a dark, microwave-size cube glinting in the foamy Gulf waves.

The 30-year-old with a thick goatee had been trying to eke out a clean living as a fisherman after previous weapons and drug convictions. But he could feel his heart pounding as he pulled the package onto his boat. He sliced through the soggy plastic lining and glimpsed the white powder inside: more than 40 pounds of bone-dry, pure cocaine. On the street, he quickly calculated, it would sell for at least a half-million bucks.

“I never in my wildest dreams would have thought it would happen to me,” Breeding says. “What would anybody do in that situation?”

For the tens of thousands who fish the sun-baked waters around Florida, that’s more than an academic question. Because a checkerboard of agencies, from the Drug Enforcement Administration to the Coast Guard to local cops, deals with drugs discovered at sea, there are no real stats on just how much cocaine and weed is found floating in the ocean after being jettisoned by smugglers fleeing the authorities or caught in bad weather.

But in just the past two years, at least 600 pounds – upward of $5 million worth of drugs – have been found by Florida fishermen and beachgoers, according to police and news reports gathered by Miami New Times. Far more was surely found and resold on the black market without being reported.

“We hear about maybe four or five cases every year,” says Dep. Becky Herrin, a spokesperson for the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office in the Keys. “But, of course, we would have no way of knowing how often fishermen find drugs at sea and decide to keep them or resell them.”

That’s a regular occurrence, says Travis Kvadus, who has been fishing off Key Largo for more than 15 years. “You spend enough time out there, you’ll find drugs every five years or so,” Kvadus says. “A lot of times, you’ll see it and you don’t even fuck with it… But every year, guys do keep a haul and resell it.”

Drugs have been washing ashore or riding currents off Florida ever since the Caribbean and Latin America became a key transshipment point for marijuana and then cocaine between the ’50s and ’70s. By the early ’80s, so much discarded weed was washing ashore that beachfront towns were struggling to get rid of it. In one busy weekend in 1983, dozens of 50-pound bales came in with the tide in Surfside, Bal Harbour, and Haulover Beach Park. It overfilled evidence rooms to the point that Surfside’s police chief had to lock piles of it inside his own office.

“They finally got some room up there, and all of a sudden there were 16 more bales,” a police spokesman lamented to the Miami Herald, which termed the contraband “Key West mullet.”

By the mid-’80s, a Miami company was making a hefty profit charging cops $45 per pound to incinerate all the drugs floating around offshore. And in 1985, one of the Herald‘s own editors found a bundle of pot while sailing back from the Keys. “Floating, within our grasp, was a tax-free ticket to happiness,” wrote Scott Spreier, who ultimately left the drugs at sea.

As the Colombian cartels crumbled in the early ’90s, drug shipments slowed across the Florida Straits. But 20 years later, it’s clear that millions of dollars of coke and weed are still regularly ditched in the ocean and then discovered by Floridians.

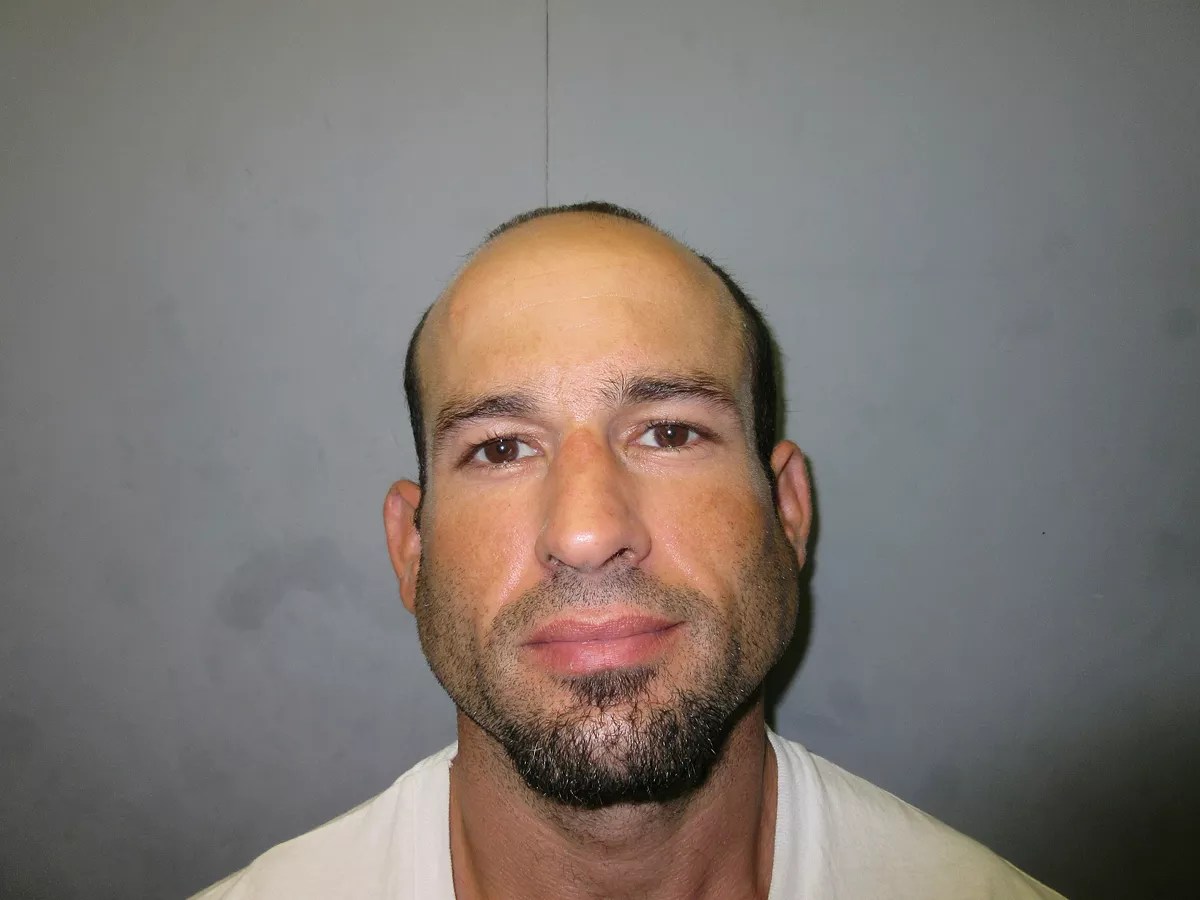

Jeremy Macauley found 15 kilos of cocaine at sea in June 2015, police say.

Courtesy of Monroe County Sheriff’s Office

Some people quickly turn in the catch, like a Destin-based fishing crew that reeled in 25 kilos of cocaine in 2013. When 21 kilos washed up on a beach a few miles down the Panhandle two years later, beachgoers likewise alerted the cops. In August 2015, an off-duty Charlotte County sheriff’s deputy cut out the middleman; he was fishing 25 miles off the coast near Sarasota when he hooked 25 bricks of yeyo, each weighing two kilos.

But other people make the opposite choice. Nobody ever hears from the ones who get away with it. And there are plenty. Just ask Kvadus. “I’ve found marijuana twice,” he says, noting with a grin that both cases are now outside the statute of limitations.

Ask around in any Keys dive bar, though, and you’ll hear about plenty who didn’t handle it right. Take, for instance, 24-year-old Taylor Oldfield and his friend 29-year-old Norman Fuhrman, who found 24 kilos of coke while fishing the Keys in August 2015. The buddies tried to sell the haul in Orlando but ran into a common problem: They were fishermen, not drug dealers. They were able to unload about seven kilos for $72,000 but then tried to sell a brick to an undercover cop at way below market value. “Not a real great idea” is how a sheriff’s spokesman summarized their caper.

In January 2016, Panama City ex-con Thomas Breeding made the same choice after hauling in 45 pounds of Colombian gold. It wasn’t a snap decision. “I rode around with [the cocaine] for five or six days, using it as a footstool, catching grouper,” he says. “I was so high on that stuff I don’t know how I was able to function.”

One day, he got back to the docks, quit his job on the spot, and set out to sell the coke. For six months, he made hundreds of thousands of dollars until the feds were tipped off. He was arrested in June, pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to six years in prison. “I regret what I did,” Breeding says from jail. “[But] I am thankful that nobody lost their life.”

In the long history of Florida and drugs, though, it’s unlikely that any floating package of cocaine has led to quite as much devastation as the 15 kilos that a perpetually sunburned felon named Jeremy Macauley hooked off the coast of Key Largo almost two years ago.

Ortiz planned to open a tattoo shop in a storefront next to the barbershop where he sometimes cut hair.

Photo by Tim Elfrink

A few hours before he was shot through the head and left to die, Carlos Ortiz paced his house, composing a text on his girlfriend Tara’s smartphone. He was desperate. For months, he’d been dipping into the cocaine he was supposed to be selling. If he was going to fulfill his dream of opening a tattoo shop, he needed more money and more blow.

And he knew how to get it.

First, he made a copy of a video shot by his drug source: Jeremy Macauley, a hulking fisherman who’d drifted to the Upper Keys after a rough childhood. Filmed two months earlier, it showed Macauley posing in front of the haul of his life: 33 pounds of pure coke, fished straight from the waters off Key Largo. “Yeah, boy, get that goddamn money, nigga!” Macauley yells.

Ortiz texted the video to Macauley with a simple threat: He’d give the clip to the cops if he didn’t get more money and drugs, fast. “This shit is gonna be crazy,” Ortiz warned as morphine and oxycodone surged through his blood.

Within hours of hitting send on that October 15, 2015 text, Ortiz and Tara Rosado would be dead. Their murders marked a horrific end to a self-destructive romance and shattered their social circle of misfits, many of whom were trying to make a second or third go of life in the Keys.

“I knew he was selling shit out of their house. It wasn’t good. But she didn’t want to listen.”

Rosado certainly needed redemption. Born and raised on Staten Island, she was just 18 when she had her first son. She married a man named Juan Rosado in 2010, and by the time she was 23, she had two more kids with him. (The names of her children have been changed in this story to protect their identities.) The marriage was rocky, and Rosado struggled with substance abuse, though her father says she was never an addict. When her parents moved south to Tavernier in 2014, they bought her a double-wide mobile home on quiet Cuba Road for $140,000. They hoped she’d find a fresh start on a tranquil street populated with fishermen and retirees.

Rosado found work as a lifeguard and at Domino’s Pizza, and volunteered at her kids’ elementary school. But her new tropical home didn’t solve her problems: Her husband was investigated by the Department of Children and Families for threatening their kids, and she filed for divorce in October 2014. For all of her own struggles, her friends say, Rosado’s kids were the center of her life.

“She was always a mother first,” says Travis Kvadus, her neighbor. “She was a bubbly type of person, but her kids were always the first thing on her mind… Some people aren’t like that. They tell their kids to deal with their problems themselves or just tell them to stop crying. But she was a soother.”

Kvadus and Rosado were fast friends. She was charismatic and easygoing; even after long hours delivering pizzas for minimum wage and shepherding her kids, she loved talking to friends in her kitchen. “Tara was always trying to feed me chicken soup, hamburgers, everything,” Kvadus says. “She’d see me outside and say, ‘Come over, and I’m not gonna take no for an answer.'”

Within six months of divorcing her husband, Rosado began dating Carlos Ortiz. Right away, Kvadus was worried. He’d known Ortiz for years. Rosado’s new boyfriend was a handsome, outgoing barber and a wannabe tattoo artist with a real talent for sketching. But he was also a hopeless addict. He’d been arrested for everything from marijuana trafficking to armed robbery, and Kvadus knew that when he wasn’t in custody, he was usually strung out on heroin or morphine and sleeping on his friends’ couches.

“I would always tell Tara: ‘Look, there’s plenty of fish in the sea,'” Kvadus says. “I knew he was selling shit out of their house. It wasn’t good. But she didn’t want to listen. She thought she could change him.”

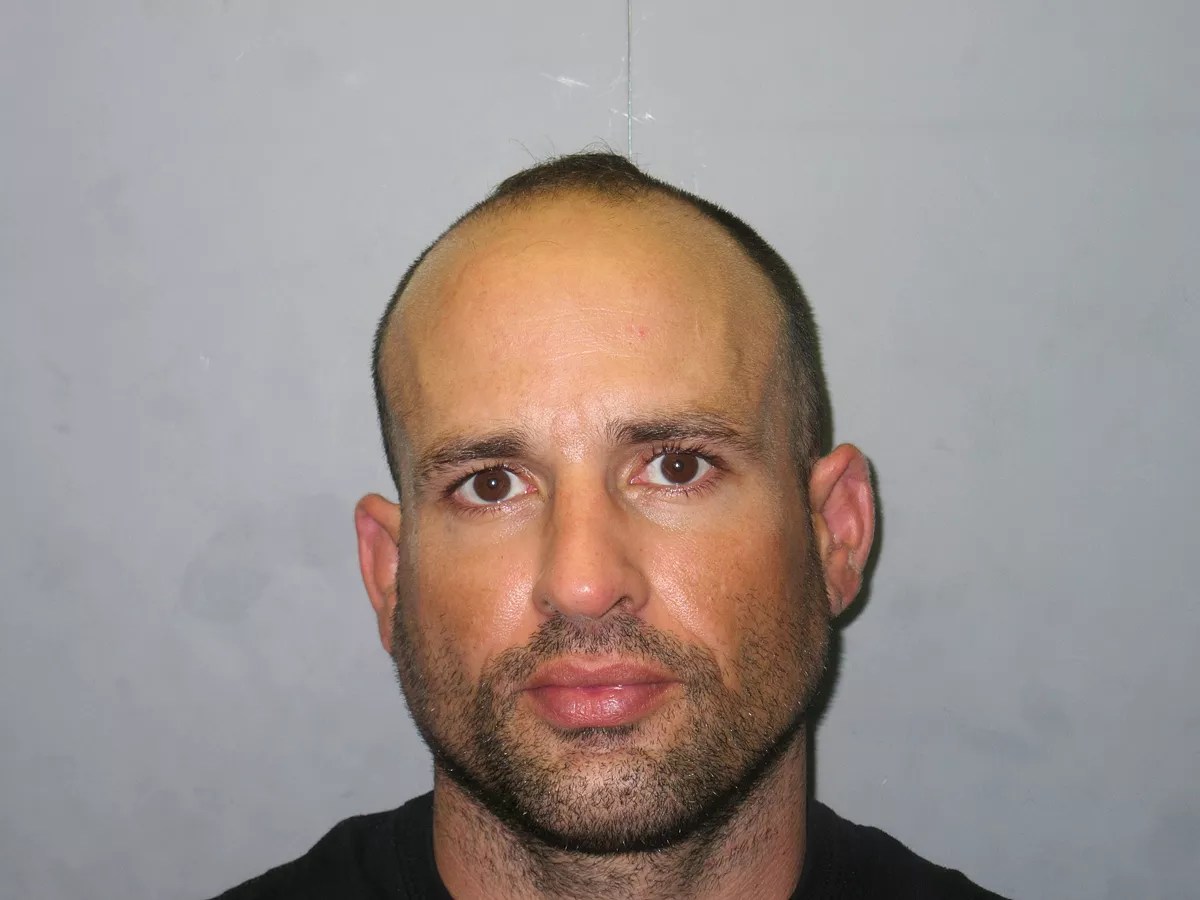

Adrian Demblans is accused of driving Macauley to the murder scene, but an inmate says his twin brother Kristian later confessed to being the triggerman.

Courtesy of Monroe County Sheriff’s Office

Whatever hope Rosado had of removing drugs from their lives dissolved in June 2015 when that mammoth square grouper showed up in Key Largo.

It all began with another of Kvadus’ friends: Jeremy Macauley. Born in 1983, Macauley had grown up in St. Petersburg with a single mother. His dad, a PTSD-scarred Vietnam vet and drug addict, was never around. Macauley racked up a long juvenile record. At the age of 16, he was convicted as an adult of felony burglary and sentenced to two years in prison. When he got out, he moved with his mom to Key Largo and started over as a fisherman on a boat called the Sea Horse.

Macauley married and had two kids, including a boy with autism. Like Rosado, he was known as a devoted parent. “He wasn’t a bad guy,” Kvadus says. “Jeremy would always take off work to go do something with his kids, to go to a recital for his daughter, go to school for Father’s Day.”

But $500,000 worth of cocaine can tempt anyone – and that’s exactly how much coke multiple witnesses later told police Macauley and the Sea Horse‘s captain, Rich Rodriguez, pulled in during a trip in June 2015. (Rodriguez declined to talk to New Times and has likewise clammed up when pushed by police about the drugs; he hasn’t been charged in the case.) No one disputes that soon afterward, Macauley began slinging cocaine around the Upper Keys.

Like any fisherman turning to drug dealing, Macauley needed help from the pros. He contacted Ortiz, who had plenty of connections in Key Largo’s drug scene. Then he drafted Adrian Demblans, a local character who police say would play a key role in the violence to come.

Among the troubled men rebuilding their lives on Key Largo’s fishing docks, Adrian and his twin Kristian stood out. The brothers were muscular, tanned, and intimidating. They came from a wealthy Cuban-American family in South Miami-Dade, where they grew up. At Palmetto High School, they both battled their way to varsity slots on a feared wrestling squad. Adrian in particular was a force, going 11-2 his junior year in 1999 and making the All-Dade third team.

But the Demblans twins were always on the verge of serious problems. “They weren’t bad kids, but they needed a lot of guidance,” says David Soderholm, their wrestling coach. When they did get in trouble, he says, “they would have done anything to cover for each other.”

That trouble materialized soon enough for the Demblans boys.

In July 2006, the then-25-year-old Kristian was stopped by police near the Dolphin Mall with two pounds of weed in his trunk. The next month, the feds closed in on his brother. A confidential informant told ATF agents that Adrian was an “armed narcotics distributor,” and promised to set up a sting. A few days later, Adrian delivered 35 grams of free-base coke in a ziplock bag to a narcotics cop as the feds swooped in. He later pleaded guilty to two counts of cocaine trafficking and served two years in prison.

Unlike most of their Keys friends, the Demblans were never hard up for cash. Their parents own a successful investment firm and property from Key Largo to Sunny Isles Beach. “[Adrian] was handed a charter boat business by his parents,” a friend later told investigators. “I don’t know why he does the shit… because he sells shit too. I don’t know why he does that, but he doesn’t need to.”

Whatever their reasons, the Demblans brothers were well known in the Upper Keys for their drug ties. According to the cops, Macauley eventually carved up his find and enlisted Carlos Ortiz, Adrian Demblans, and others to help sell it.

As the cash began pouring in, Macauley’s life changed. He bought a new truck and draped gold jewelry around his neck.

Ortiz also made money. Macauley rented out a storefront next to the barbershop where Ortiz worked and helped fund that tattoo and smoke shop Ortiz had always wanted. He called it Ink-Your Dreamzzz. Ortiz spent weeks tearing up tile floors and installing flat-screen TVs and tattoo gear. But he was also using drugs. Steele Hancock, a friend, noticed him deteriorating in September and October 2015. Asked later by police about the narcotics Ortiz was using, Hancock said, “It would probably be easier to name the drugs he wasn’t doing. Cocaine, pills, and heroin… He got himself into really bad debt with drug dealers.” (Rosado, too, had started using cocaine and oxy with her boyfriend.)

By early October, Ortiz was ready to try anything. “He asked me: ‘You know any licks I could hit?’ Which means, like, any drug dealers he could rob,” Hancock told police.

As Ortiz’s drug supply ran low, he feuded with Macauley over the unfinished tattoo shop (which Hancock suggests might have been meant as a front to launder the cocaine profits). The day before his murder, Ortiz looked “like he hadn’t slept for three days. I’m just like, Holy God,” Hancock said.

That day, October 14, a strung-out Ortiz told Hancock he had a new idea to get cash and coke.

“‘Hey, remember I told you that these guys found a bunch of stuff on the water? I’m in a lot of trouble. I need a big amount of money… I’m gonna try to extort these guys,'” Hancock recalled Ortiz saying. “‘Either you guys give me… drugs and money, or I’m gonna go to the cops and tell them what you found.'”

Hancock was horrified.

“Please, for the love of God, don’t go there,” he told Ortiz. “That’s scary business.”

The barbershop where Ortiz worked.

Photo by Tim Elfrink

Here’s what Monroe County Sheriff’s deputies encountered inside 238 Cuba Rd. just after 2 p.m. October 16, 2015:

Ortiz, clad in black gym shorts and a black tank top, had taken a single .45-caliber bullet to the forehead; it shattered his skull, pierced his brain, and exited cleanly behind his left ear. Rosado wore flip-flops, dark sweat pants, and a black shirt that read “Sexy” in gold glitter; someone had held a gun to the back of her head and pulled the trigger, firing a round that entered her brain and came out near her right eye.

Who would execute a young couple in their own bedroom on a quiet Thursday night in the Keys? Technicians and cops swarmed the double-wide. They marked bullet holes and cataloged evidence while a specially trained officer sat with Rosado’s traumatized children next door. A small team of detectives huddled. They knew they would have to find answers fast.

The Keys are no utopia. Heroin use has risen on the islands in recent years, and deputies deal with plenty of sexual assaults and violent fights. But murder is extremely rare. Just one homicide had been reported in all of Monroe County in the previous two years.

Police started where such murders usually begin: with Rosado’s ex-husband, Juan. He had stayed nearby after their divorce, working at a Home Depot in Homestead. Detectives quickly tracked him down but just as rapidly ruled him out. He had an ironclad alibi: He had worked the night of the murder and then stayed with friends.

Kvadus bought a gun and stayed up late, staring at his grainy surveillance cameras.

Then detectives homed in on Ortiz’s drug problems. One spent hours grilling Kvadus. Police became suspicious after learning the neighbor had erased some of his surveillance footage before they arrived on the scene. But he explained that he did that every morning; otherwise, his computer memory filled up. “They kept yelling, ‘Why’d you delete it?!’ When I explained, they were like, ‘Bullshit!'” Kvadus recalls. “I just said, ‘Yo, bullshit to your bullshit.'”

The cops eventually dropped Kvadus as a suspect. As days stretched into weeks, paranoia peaked, particularly among those who knew Ortiz and Rosado. Kvadus bought a gun and stayed up late, staring at his grainy surveillance cameras whenever a strange car came down the dead-end street. “It was pretty bad,” Kvadus says. “It was the fear, just staying up and worrying.”

Another friend who cooperated with police bought two muscular Belgian Malinois dogs and hammered thick plywood over his bedroom windows to shield himself from potential drive-by shootings. For all he knew, Ortiz had crossed a Colombian cartel.

The Keys deputies did have one solid clue: At the murder scene, they’d found Rosado’s smartphone. They watched the video of Macauley bragging in front of his giant pile of cocaine and read the vaguely threatening message about “things getting crazy.” But Ortiz’s white iPhone was missing.

Where was it? they wondered. And where was the murder weapon?

Three weeks after the killings, police caught a break. A fisherman working a canal just off Key Largo spotted a gun in the crystalline water and called it in. A police dive team fished out a rusty Colt .45 Government Model with ammo similar to the bullets that had killed Ortiz and Rosado. A few days later, another dive team turned up Ortiz’s white iPhone just a few yards away.

In the meantime, police extracted Ortiz’s text records from the night of the murder. They showed a flurry of four messages to Macauley in the hour before the murder. In one, Macauley replied he was on his way to the house on Cuba Road. The phone’s photo drive revealed that Ortiz had stockpiled other incriminating pictures of Macauley’s drug dealing.

Next, the cops learned about Adrian Demblans. A friend of his told police that the night of the murders, Adrian and Jeremy had dressed in all black and borrowed her gray SUV. When they returned, she had heard them arguing: “It wasn’t supposed to go down like that!” one said. (That same SUV, police noted, was seen on surveillance video outside the murder scene. One man resembling Adrian Demblans sat in the driver’s seat while another, who appeared to be Macauley, walked into Rosado’s home for about five minutes.)

Then police persuaded Adrian’s girlfriend to cooperate. She added another clue: In late February, she said, Adrian had borrowed scuba gear and hitched a ride to the same canal where police had found the murder weapon and Ortiz’s missing phone. He told her he was looking for “keys” he had dropped there. Adrian emerged from the water an hour later, she said, angry and empty-handed; on the ride home, she heard him call Macauley and mention a gun.

By last spring, detectives had sketched a vivid picture: a fisherman in over his head, trying to unload kilos of cocaine; a motley crew of drug addicts, some with dangerous tempers and violent pasts, helping him sell it; and a young mother and her children caught between a desperate blackmail attempt and its target.

Detectives had more than enough evidence. With a grand jury indictment in hand, they pulled up to the docks in Islamorada March 28, 2016. After the Sea Horse nudged into its slip and disgorged a deck full of tourists gripping the day’s catch, the officers slapped handcuffs on Macauley. Adrian Demblans was already in custody in an unrelated case.

In court, prosecutors laid out their version of events: Macauley had ridden with Demblans to the house on Cuba Road, executed Ortiz and Rosado, and then tossed the gun and iPhone into a canal with Demblans’ help. Prosecutors charged Demblans with being an accessory after the fact to a capital murder. Macauley faced two counts of first-degree murder and one count of armed robbery.

The news tore through Key Largo’s quiet side streets.

“I was like, ‘Holy shit,'” Kvadus says. “It’s not the Demblans’ part that was a shock. It was Jeremy [Macauley]… I never would have figured him as a triggerman in a crime like this.”

Kristian Demblans

Courtesy of Monroe County Sheriff’s Office

Kvadus reclines shirtless in a lawn chair beneath a tiki hut adorned with tropical knickknacks. Plastic starfish hang next to a wooden sign: “Ocean, sun, sand, surf. Just another day in paradise.” As a salty breeze drifts through his yard on Cuba Road, Kvadus knows he’ll never forget what happened next door: The blood. The bodies of his friends on the floor. The kids, traumatized and tear-streaked.

“You can still see the patched-up bullet holes on the side of the house if you look over our fence,” Kvadus says, gesturing at Rosado’s double-wide.

A year and a half after the carnage, prosecutors say the men responsible are in custody. But the case looks less clear-cut by the day. Another man killed by a gunshot wound to the head has thrown the prosecution into chaos. And Macauley’s lawyer says a jailhouse confession is set to sink the whole case.

“They got the wrong guy, plain and simple,” attorney Ed O’Donnell says. “It was the Demblans all along.”

The first major chink in the prosecution’s armor appeared in October when a Monroe County jail inmate named Eric Lansford asked to speak to detectives. Lansford had been in the clink since May on a burglary charge and was just a month from freedom when a new cell mate showed up: Kristian Demblans had been popped in September for heroin and cocaine dealing.

After just a few days, Lansford told police, Demblans spilled his whole story. Macauley had nothing to do with the murders. Demblans confessed he’d actually pulled the trigger in both the killings and said he would have shot the children too if he had known they were there, Lansford claimed.

Prosecutors and police insist Lansford’s tale is just jailhouse BS. “It is not uncommon in this type of case to have rumors, speculation, and attempts to derail the case to help the bad guy,” Sheriff Rick Ramsay told reporters.

“It is not uncommon to have attempts to derail the case to help the bad guy.”

But O’Donnell the lawyer says Lansford’s testimony is proof the cops royally botched their investigation. He cites other evidence: Macauley’s wife says her husband went fishing the day of the murder, came straight home, and left only to grab some milk. Cell records show his phone never left his residence that night. And Lansford, whose sentence was ending, had nothing to gain by pointing the finger at Demblans. “Besides, I’ve got two other witnesses who put [Macauley] at home the whole time,” O’Donnell says.

As for Adrian Demblans, many in Key Largo expect he’ll strike a deal to testify against Macauley. (His attorney declined to comment on the record for this story.)

All of that courtroom drama will have to wait. On November 17, Manny Madruga, the veteran prosecutor handling the case, was found dead in his Key West home with a single gunshot wound to the head. Police ruled the death a suicide; after 27 years on the job, Madruga had recently learned that the Keys’ newly elected state attorney planned to fire him. He was distraught.

Because the new state attorney had worked with Macauley’s defense lawyer in the past – a potential conflict of interest – Monroe County prosecutors transferred the case to West Palm Beach.

As Macauley and Adrian Demblans await separate trials in May, a debate has gripped Key Largo. Could Jeremy Macauley really have executed two people as children slept in the next room? Did he have that kind of violence in him?

“He doesn’t strike me as somebody who would murder somebody,” Steele Hancock, Carlos Ortiz’s friend, told police. “He may look a little rough around the edges, but the guy’s got kids and takes care of his kids well.”

Adrian Demblans is a better suspect, Hancock says: “Another thing I’ve heard about Adrian is that he’s fucking crazy and that, you know, he is crazy enough to kill somebody.”

But Kvadus has come around to the idea that Macauley is the murderer. If Ortiz had actually gone to the cops, Macauley would have lost his fishing gig and possibly gone to jail for years. “People will do a lot to defend their family and their work,” Kvadus says. “And that’s exactly what Carlos was threatening.”

One thing is certain: Huge bales of drugs are still floating around the Keys, waiting to be discovered. In just two months, September and October 2016, more than 400 pounds of weed washed up around the islands. Cops urged fishermen to turn in the drugs. “Attempting to keep the suspicious package can place you in danger,” one local deputy warned.

There’s one other point everyone agrees on: Tara Rosado didn’t deserve to die. And her three children, who now live with her parents in Tavernier, should never have had to endure the 15 hours they spent locked inside their home with their mom’s body.

“Tara was 100 percent innocent,” Hancock told police. “Her kids were in the house, and that just takes a fucking monster, if you ask me, to do that to her, not a human being.”

Adds Kvadus: “She was a good mother. She just had poor choice in men. It’s such a shame.”

Update 11/16/2017: Jeremy Macauley has been convicted in the murders of Tara Rosado and Carlos Ortiz. He faces life in prison.