Illustration by Brian Stauffer

Audio By Carbonatix

For decades, Hollywood and horse racing stood atop parallel foundations of inconvenient truths. Tinseltown looked the other way when powerful men behaved badly toward aspirant actresses – until Harvey Weinstein made it impossible to avoid the issue in 2017. And the Sport of Kings quietly euthanized thoroughbreds in significant numbers – until the 2019 meet at Santa Anita Park outside Los Angeles rolled around.

With the drought-plagued region fresh off an epic spate of unseasonable rain, horses at the self-styled Great Race Place began dropping like flies: 23 died while training or competing at the track between December 26, 2018, and the end of March 2019. By November 3, when the prestigious Breeders’ Cup World Championships concluded, the death toll stood at 37 horses. The last to die was Mongolian Groom, who was fatally injured while running in the two-day event’s marquee race, the Breeders’ Cup Classic.

According to statistics maintained by the Jockey Club – the 126-year-old, tax-exempt umbrella organization that, in the words of its CEO, Jim Gagliano, “was founded to bring order to racing in America” – through 2018 the death rate at Santa Anita has consistently hovered slightly above the national average of 1.69 fatalities per 1,000 horses that enter the starting gate.

Nevertheless, the press leaped on the Santa Anita story – and in the process brought the sport’s stubbornly devil-may-care establishment to its knees.

“We know what the stakes are and understand that we might be the place that kills horse racing in California,” Tim Ritvo, chief operating officer of the Stronach Group, which owns Santa Anita, told the New York Times last April.

Yet the precise cause of the first-quarter spike in fatalities remains difficult to pin down. Astute observers theorize it could have been the peculiar weather’s impact on Santa Anita’s racing surface, the promiscuous administration of drugs to horses, a propensity to run them too frequently or when they were unsound, or a combination of all of the above. But one thing was certain: Public outcry all but forced a virtually unprecedented three-week suspension of racing and a regulatory epiphany for the Stronach Group, which counts Gulfstream Park in Hallandale Beach among its many equine properties. (Gulfstream ranks slightly below the Jockey Club data’s fatality average, which has been slowly dropping for a decade.)

“We’ve been doing this for six years, and we’ve had some starts and stops,” says Patrick Battuello, founder of Horseracing Wrongs, a New York-based nonprofit that seeks to put an end to the sport in the United States. “But for whatever reason, Santa Anita became the tipping point. It’s to the point now where every death in California is being reported, which is unprecedented.”

Even some of the sport’s smartest objective observers, including longtime New York Times scribe Joe Drape, agree horse racing has reached a nadir in terms of public perception.

The start of the 2019 Pegasus World Cup race at Gulfstream Park.

Photo by George Martinez

“This is what it has taken to get to this: an intense focus on the death of horses,” says Drape, who in September busted the California Horse Racing Board and hall-of-fame trainer Bob Baffert for being perilously slow to report a drug violation in the Santa Anita Derby by the eventual 2018 Triple Crown champion, Justify. “I guess the shame of it is, they knew this was coming. I’ve got congressional testimony back to the ’80s where they were talking about these issues. You just sort of had the perfect storm at Santa Anita: bad weather, a management group that’s twisting arms, cheaper races, cheaper racehorses, trying to get bigger fields. It’s a very progressive state with a huge population of animal lovers, and I think it just snowballed there. Once it popped up on the Today show, I was getting a lot of people who didn’t give a rat’s ass about horse racing saying, ‘Horses die? Why?'”

“I was getting a lot of people who didn’t give a rat’s ass about horse racing saying, ‘Horses die? Why?’ ”

Drape believes the sport is “one catastrophic breakdown in the [Kentucky] Derby away from being in real trouble. The 3 million hardcore players don’t think it’s a level playing field. They think people cheat, and there’s no transparency in the medication rules. The people who are just there for the spectacle don’t want to see a horse or a jockey die. That’s a helluva needle to thread.”

The Stronach Group appears to be trying, however.

This past December 14, Gulfstream’s owners announced a ban on all race-day medication – including Lasix, a commonly used diuretic that prevents horses from bleeding in their lungs – for its lucrative Pegasus World Cup races, which will be contested this Saturday, January 25. The two Pegasus races on Saturday’s card – a $3 million race on the dirt track and a $1 million contest on the turf (i.e., grass) – are open to horses aged 4 or older. According to a media release, Pegasus entrants will be subjected to “stringent out-of-competition testing and enhanced medication protocols, including a 14-day stand-down on intra-articular injections [and] the complete transparency of veterinary records for the 14-day period leading up to the Pegasus World Cup Championship Invitational Series races.”

Though such standards, which have long been observed in Europe and Japan, are not being enforced for the balance of the Gulfstream meet, the Stronach Group has implemented similar rules at Santa Anita, which suffered its 37th fatality of 2019 when Mongolian Groom was euthanized after breaking his leg while running in perhaps the nation’s most prestigious race, the $6 million Breeders’ Cup Classic, in front of a crowd of nearly 69,000.

The Stronach Group’s recent moves have elicited praise from none other than Kathy Guillermo, senior vice president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), who tells New Times the company is doing more to try to clean up the sport than “anyone else has done in a generation.”

Some keen observers say the continued existence of American horse racing itself is at stake.

In his storied career, veteran breeder and horse owner Arthur Hancock III has raised three Kentucky Derby winners: Gato Del Sol, Sunday Silence, and Fusaichi Pegasus. Along with PETA, the Jockey Club, the Stronach Group, and other high-profile entities, Hancock supports the Horseracing Integrity Act of 2019, a federal measure cosponsored by more than half of the U.S. House of Representatives that would create a single national drug-testing authority to supersede the various doping rules that are in place in 38 state commissions.

“If we don’t get rid of these drugs, I don’t think we’re gonna have a sport because of what it does to the horse and public perception,” says Hancock, a third-generation horseman whose grandfather, the first Arthur B. Hancock, founded one of American horse racing’s iconic institutions, Claiborne Farm, in 1910.

Drape concurs. “They’ve been saying, ‘That’s just racing,'” he says, referring to the industry’s response to on-track deaths. “But now they’re on the news getting banged all the time on this. It’s a world that has Netflix, sports betting, casinos – it’s just a crowded marketplace for fuck-around time. You talk to smart people in the industry, they really do think it’s a tipping point.”

The Gulfstream Park paddock before the first race on Pegasus World Cup day 2018.

Photo by Neil Johnson/Courtesy of Gulfstream Park

Frank Stronach was reared in Austria before moving as a young adult to Canada, where he amassed a multibillion-dollar fortune in the automotive-parts industry. Now age 87, the Stronach Group’s patriarch has grown ever more eccentric in his endeavors, wholly befitting of the mélange of Sunshine State batshittery that makes for enduring memes.

Enter – or even drive past – Gulfstream Park on Federal Highway, and you can’t help but notice a 12-story bronze statue of the winged horse Pegasus stomping on a dragon. In a recent court filing, Stronach described his colossus thus: “The sculpture stands 110 feet tall and it reminds us that mankind is always influenced by the good spirits and the bad spirits – the Pegasus and the dragon. Every day, we are faced with decisions – is it right or wrong? Good or bad? Constructive or destructive?”

Did we mention Stronach has an identical statue in storage in China?

Stronach’s late-in-life exploits have led to a lawsuit by his daughter, Belinda, the current president of the Stronach Group, alleging Dear Old Dad squandered at least $680 million of the company’s fortune on “passion projects,” including, in addition to Pegasus Squared, an electric-bicycle business and a pumpkinseed-oil venture. The Washington Post reports that in a countersuit, father accuses daughter of “diverting funds meant for projects such as his grass-fed cattle farm to support her extravagant lifestyle” and seeks to have her removed as the Stronach Group’s controlling officer.

The soapy familial squabbling might help to explain why the Stronach Group waited until two months before race day to announce the medication changes for the Pegasus Cup. At the same time, the Stronachs dramatically reduced the cumulative purse, which, at $4 million, pales in comparison to last year’s combined $16 million pot. (Last year, owners had to pony up $500,000 per horse as an entry fee, which the Stronachs have scrapped for 2020.)

The changes didn’t please everyone.

Speaking to the industry publication Horse Racing Nation, prominent thoroughbred owner Gary West said he was “mystified, bewildered, and upset” by the late notice, declaring, “This is one of the biggest changes in a purse structure in the history of racing, and I think the Stronach Group has handled it very poorly.”

West, who owns Maximum Security – the horse that was disqualified and placed last after being the first to cross the finish line of last year’s Kentucky Derby (another recent blot on the Sport of Kings) – says he now intends to ship the horse to Riyadh to compete in the inaugural Saudi Cup. “Why should I run for $3 million when I can run for $20 million four weeks later?” he explains.

Asked to comment on West’s snub, the Stronach Group sent New Times the following statement: “We have had great conversations with Mr. West and appreciate his candor and passion for the sport. While it may have been preferable to announce the changes sooner, we are comfortable with our decision.”

In any event, the fields for the Pegasus races promise to be strong ones. And there’s no denying the Stronach Group has committed considerable resources to marketing a race for older horses at a time when, as Gina Rarick, who was born in California and grew up in Wisconsin but now trains thoroughbreds in France, puts it, “the whole program in America has been geared to the sales ring instead of the racecourse.”

Rarick is alluding to the fact that the past half-century has seen U.S. horse racing increasingly dependent upon the so-called Road to the Triple Crown, a three-race series – the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes, and the Belmont Stakes – that plays out each spring and is restricted to 3-year-old horses. Despite a widespread misconception among people who don garish hats and dust off their mint julep recipes once a year, the Derby and subsequent Triple Crown tilts do not feature the best horses the sport has to offer. Three-year-olds are the equine equivalent of gangly human teenagers when compared to horses like last year’s Pegasus Cup victors, City of Light (dirt) and Bricks and Mortar (turf). Sure, there’ll be the occasional equine LeBron James, but they’re the rare exceptions that prove the rule. And a horse that sweeps the Triple Crown is almost guaranteed to be retired to the breeding shed for a lucrative sum posthaste.

It’s not that Rarick objects to promising fillies and colts commencing their racing careers at age 2.

“The earlier you send them, the longer they last,” she says. “It’s like any athlete: You start them as soon as you can start them because then their body adapts to what they’re doing. But you have to be very vigilant to give them the breaks and the time they need. Some 2-year-olds are really precocious. Others aren’t.”

Fellow expatriate Bill Barich, a frequent New Yorker contributor whose 1980 memoir Laughing in the Hills is a classic entry in the thoroughbred writing canon, draws a distinct line between how racehorses are treated in the United States and abroad. “Medication-free racing is a good first step, but horses in the U.K. and Ireland are treated more kindly in every other way too – from living on a farm or trainers’ yards instead of stalls on the backside, and running only when they’re truly fit,” says Barich, who now resides in Ireland most of the time. “U.S. tracks aren’t being realistic if they think they can hold nine or ten races six or seven days a week without more horses breaking down more often.”

Adds Horseracing Wrongs founder Patrick Battuello: “The deaths are what draw the most attention. But for me, the worst of it is the unrelenting confinement and isolation. These animals are kept in stalls for 23 hours a day.”

Despite strong bipartisan support in both chambers of Congress, the Horseracing Integrity Act has languished. Hancock and other backers expect that to change, noting the House is likely to schedule hearings very soon. But even if the bill does clear the House, it almost surely will die in the Senate, as long as Mitch McConnell rules the roost. The majority leader has yet to take an official position on the legislation, but Drape and Hancock say the longtime Kentucky senator has made it clear he won’t support the bill unless Churchill Downs drops its opposition to it. (McConnell’s office did not respond to several requests for comment.)

“The proposed federal legislation, which is very controversial across the industry, is laudable in seeking fairness of competition through medication reform, a concept we absolutely support, but lacks broad consensus on how it will work, how it will be funded, and what agency has the expertise and willingness to provide the necessary oversight,” Churchill Downs Inc. executive director Mike Ziegler tells New Times in a statement. “The bill also does not address track-safety protocols, which is another matter for which we remain deeply focused and very active.”

The National Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association (HBPA), a group that represents owners and trainers, also opposes the Horseracing Integrity Act. Eric Hamelback, CEO of the HBPA, speaks of the bill with rhetoric reminiscent of what the firearms lobby has long used to wear down gun-control advocates.

“Ultimately, this bill is in violation of Tenth Amendment rights,” Hamelback argues, referring to the U.S. Constitution’s provision enshrining states’ rights. “It takes away from what the states currently have in place and it duplicates the authority already existing in the 38 pari-mutuel jurisdictions. Many proponents of the bill proclaim, incorrectly, that every jurisdiction is different. There is extreme uniformity, but are there differences? Absolutely.” To this end, Hamelback – who once worked for Frank Stronach – advances a creative analogy: “The speed limit might be different in Alabama than it is in Georgia, but driving under the influence is illegal in any state.”

“Lasix may not be the therapeutic medication it’s made out to be, but it’s not what’s killing these horses.”

“We think it should be banned,” PETA’s Guillermo says of Lasix, which some observers argue acts as a performance enhancer when administered to horses that don’t medically need it. (Others believe use of the drug can weaken the animals’ bones.) “There’s such conflicting evidence.” When she testified at a recent state hearing about the drug, Guillermo recalls, “half the people stood up and said, ‘We can’t operate without it – it’s the most humane [way to treat horses prone to bleeding].’ But if you look at other racing jurisdictions where they don’t use it, somehow they still manage to conduct racing. If we assume it’s important to controlling bleeding, I don’t think we should have horses who are bleeding on a racetrack.”

Hamelback insists the longtime use of Lasix on race day is based on veterinary research and administered in the interest of equine health and welfare and to prevent exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage, or EIPH. “All horses have a propensity to suffer EIPH,” he contends. “It’s not uncommon in human athletes either. If you’re a marathon runner and have an EIPH episode, does that mean you’re not allowed to compete when there’s a legal medication that can help you deal with those symptoms?”

Hamelback likewise dismisses the argument that horsemen use Lasix for reasons other than bleeding. “Saying that it’s doping, that it masks other drugs or is performance-enhancing – none of those can be said to be true within an equine athlete,” he says.

Patrick Battuello believes the Lasix debate is a red herring that muddles more existential issues. “It’s maybe not the therapeutic medication it’s made out to be,” the Horseracing Wrongs founder says, “but it’s not what’s killing these horses.”

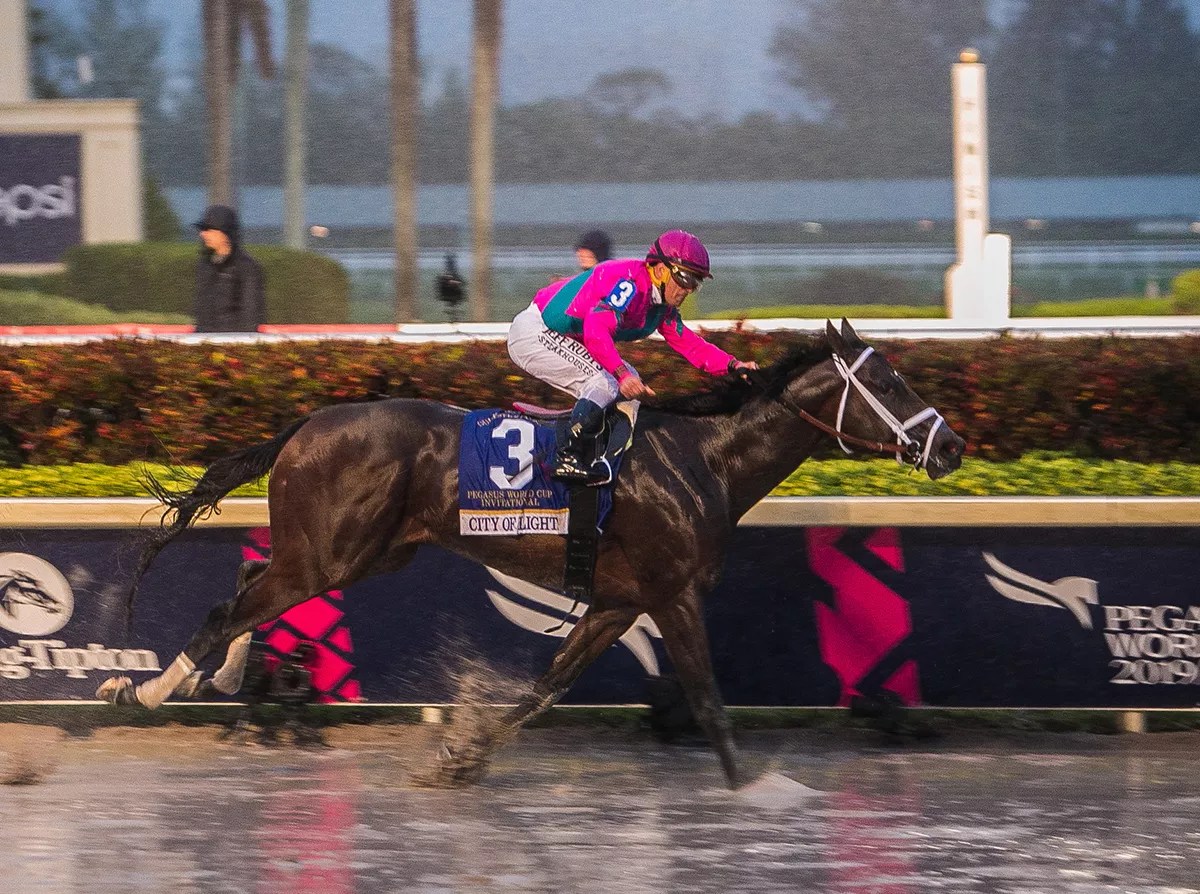

City of Light en route to victory in the 2019 Pegasus World Cup dirt race.

Photo by George Martinez

If a middle ground can be said to exist in this debate, it’s embodied by the likes of two New Yorkers: professional handicapper Jerry Brown, and Sally Eckhoff, an artist, author, fox hunter, and rider of a 24-year-old horse named Spot.

In a recent New York Times op-ed, Eckhoff urged the industry to show more concern for its equine athletes’ lifespans. “When horses are put to the most rigorous athletic tests of their lives at 2 and 3, most won’t make it that far. Plenty of 4-year-old racetrack rejects are already so arthritic they can’t be ridden for more than 20 minutes at a clip,” she wrote.

“People need to know what horses are capable of, given the right conditions,” Eckhoff continued. “And the right conditions include a fair crack at life, starting with a chance to grow up.”

Though Eckhoff says she’d be happy to see an end to races for 2-year-olds, she concedes that some horses develop sooner than others. The crux of the issue, she argues, is that “every owner should have a plan for every horse when he gets off the track. And it can’t be to just give him to some girl who wants to do dressage with it.

“I think they should be treated like children,” Eckhoff adds. “I want owners and trainers to be saddled with the responsibility of what they’re going to do with a horse when it’s 18.”

As an advocate for hardcore horseplayers, Brown stakes out a stridently pragmatic position, particularly when it comes to Lasix.

“In other countries, the pace is much slower than it is here,” says Brown, who founded Thoro-Graph, a statistically sophisticated data service used by serious bettors and horse-industry pros alike. When they race on dirt, Brown says, horses “are going all-out or close to all-out. They’re being exerted the entire way, while in these foreign countries, they’re galloping along and then going all-out in the final quarter [mile]. So the stress on American horses is far greater.”

Brown also notes that unlike the tracks in Europe, those in the States tend to be located close to densely populated metropolitan areas, which means horses stabled on the property breathe dirtier air. “For whatever reason, horses in this country tend to bleed,” he sums up. “If they’re bleeding, it’s therapeutic to give them medicine to help them. It’s not a performance enhancer. All Lasix does is keep a horse from bleeding in its lungs.”

Brown points to the 1987 Kentucky Derby, when favorite Demons Begone bled so profusely from the nostrils that hall-of-fame jockey Pat Day pulled his horse up on the backstretch and dropped out of the race. (Demons Begone would go on to compete in a handful of races but was retired to stud the following year. He died in 2001 at age 17.) If such an incident were to occur at a present-day Lasix-free Derby, Brown argues, the result likely would be catastrophic. “Anybody with a cell phone takes a picture of a horse standing on a racetrack – people will make sure that picture is in every newspaper in the world. And they won’t be asking to bring back Lasix,” he posits. “They’ll be asking to ban racing.”

Brown says the Horseracing Integrity Act includes commendable components – primarily its pledge to crack down on performance-enhancing drugs through the formation of a central governing body. But he says he would support the legislation only “as long as it does not include involving Lasix” – which it does, by banning race-day medication.

“There’s a movement that wants to end the existence of domestic animals, and they don’t realize what they’re asking for.”

As an alternative, Brown suggests providing weight-allowance incentives for owners and trainers to forgo Lasix for horses that don’t need it. As Brown notes, there’s no incentive today for trainers not to administer Lasix to their horses, and many observers believe it’s liable to provide an edge in a sport where the length of a nose can cost a stable thousands, if not millions, of dollars.

Though Rarick would like to see Lasix eradicated from the sport, she has no desire to consign her American counterparts to the unemployment line. She believes it’s up to U.S. horse racing’s power brokers to reverse the perilous course it embarked upon in Southern California last year.

“I think it wasn’t fair to Santa Anita, because those numbers are reproduced at tracks across the country,” Rarick says. “Santa Anita was the fall guy for systemic problems with American racing throughout the country. There’s a movement now, and I think it’s time for something to change. But there’s a whole young, urban population who live in a fantasyland where every animal should be frolicking in a field somewhere – and they have an ever-stronger voice now.

“We have to be vigilant on both sides of the pond,” she cautions. “There’s a whole movement that wants to end the existence of domestic animals, and they don’t realize what they’re asking for. Nature is not kind. If you let all these animals loose, they’re going to rip the shreds out of each other and die of all these horrible diseases. We need to take care of them and give them a decent life.

“But nobody wants to see a horse snap a leg in a race, so we have to do better.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the background of France-based horse trainer Gina Rarick. She was born in California and grew up in Wisconsin, not the other way around. The story now reflects the corrected text.