Photo by World Red Eye.

Audio By Carbonatix

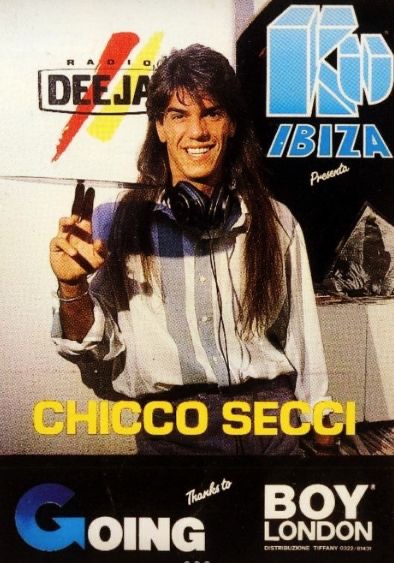

Chicco Secci remembers the date without hesitation. January 10, 1993. Miami was still years away from becoming a global dance music capital, and South Beach hadn’t yet learned how to move to house music. Clubs leaned heavily on hip-hop, R&B, and Latin pop, while DJs were expected to keep the energy high rather than guide a crowd through a journey.

House music, as Chicco understood it, barely existed here. “I don’t want to say I was the first,” he says. “But if I wasn’t the first, I was among the very few.”

When Chicco arrived in Miami from Italy, he carried with him a European understanding of nightlife. One where DJs were selectors, curators, and translators of culture, not just background noise for bottle service. Long blends mattered. Patience mattered. The dance floor was sacred. In Miami, those ideas felt foreign.

At the time, proper mixing was rare, and the concept of a DJ as an artist rather than a service provider hadn’t taken hold. Many clubs relied on Billboard charts, and deviation was discouraged. Chicco briefly became a Billboard reporter himself, receiving vinyl directly from producers across the country. But even that felt disconnected from reality. “There was no house scene to support it,” he says. “I was listening to what was being called house music, and it wasn’t.”

His first real foothold came at a small restaurant on Washington Avenue called Fellini, owned by an Italian who instinctively understood the sound Chicco was trying to introduce. Monday nights became his laboratory. There were no expectations, no pressure, just space to experiment. From there, he moved through Bash, Bourbon, Amnesia, Living Room, and eventually most of South Beach’s defining rooms as the city slowly caught up.

Courtesy of Chicco Secci.

There was one notable omission: Warsaw. The club’s insular booking culture kept him out, despite his growing reputation. “They didn’t want anyone new,” he says. “It was very closed.”

Miami, however, was changing. In the late ’90s, American clubgoers began traveling to Ibiza and returning with new ears. The Winter Music Conference brought global producers to the city. Ultra followed, transforming Miami into a destination rather than a stopover. House music didn’t just arrive. It exploded.

Chicco was already fluent. Over the decades, he found himself sharing booths with nearly every major figure in electronic music: Tiësto, members of Swedish House Mafia, Avicii, Sasha, Paul van Dyk, and longtime collaborator Benny Benassi. One night in the early 2000s stands out. Chicco was booked to open for Tiësto at Nation, a massive room that filled before midnight. Thousands were locked outside. Tiësto didn’t arrive until well after 2 a.m.

“I had total freedom,” Chicco recalls. “Nobody was telling me to play radio records.”

The crowd stayed engaged, receptive, hungry. When Tiësto finally took the decks, the release was overwhelming. For Chicco, it was proof that Miami was finally ready — not just to dance, but to listen.

That distinction matters to him. To Chicco, the DJ is a messenger. Music is information. “If you give people yesterday’s news, they already read it,” he says. That belief drives his process to this day. He doesn’t rehearse sets. He downloads tracks the same day he plays them. He spends hours digging through Beatport, Traxsource, and promo pools, chasing sounds that feel alive rather than safe.

He favors underground house, organic textures, and Afro-house before it became a formula. If a crowd needs grounding, he’ll offer what he calls “a candy”, a recognizable track, before pulling them back into deeper waters. Repetition is not an option.

“I don’t repeat sets,” he says. “That’s the job.” It’s also why he remains critical of the modern club landscape, particularly in Miami. Trends cycle rapidly. DJs mirror each other’s styles. Promoters become performers. Image often outweighs identity.

“Three years ago, everyone played EDM,” he says. “Now everyone dresses and plays the same Afro-house. That’s not evolution.”

Phones dominate dance floors. VIP sections fracture energy. Chicco doesn’t romanticize the past, but he does mourn what’s been lost. “I’d rather play for 15 people who are really listening than 1,500 filming,” he says.

His favorite rooms reflect that ethos. Pure Nature. Water. Set. And Mint, which opened in November 2001, just months after 9/11. The first night was so intense that it blew the sound system. “Nobody expected people to dance like that,” he says. The club quickly became a landmark.

Then there was The Wall. For 11 years, Chicco held a Saturday residency at the intimate Miami Beach venue. With a capacity of around 500, it embodied everything he believed nightlife should be. Focused, immersive, and communal. When it closed after COVID, something irreplaceable disappeared with it.

“These rooms don’t exist anymore,” he says. “They were jewels.”

Today, Chico lives more quietly. He rarely goes out unless he’s playing or there’s a DJ he genuinely wants to hear. He spends time producing music, refining ideas, and watching films. Recently, he played underground shows in Bogotá, where the energy felt raw and unfiltered.

“That’s what keeps me excited,” he says.

House music is now universal. Its language transcends borders. Miami helped amplify it, export it, and commercialize it. But long before the city claimed the sound as its own, Chicco was there, patiently building a culture that didn’t yet know it needed him.

He never shouted for attention. He never chased the spotlight. He just played the record and trusted that the right people would hear them.