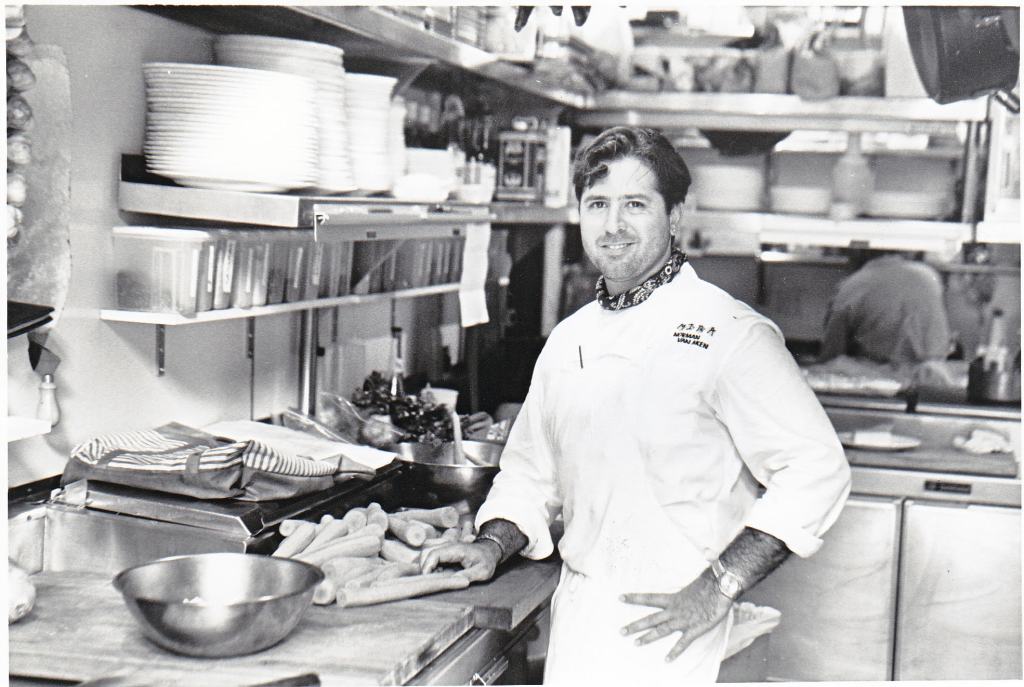

Norman Van Aken photo

Audio By Carbonatix

Before Miami was a dining destination — before Michelin stars and celebrity-backed steakhouses — there was Norman Van Aken, the Midwestern cook who decided that Florida deserved a cuisine of its own.

In the mid-1980s, long before “farm-to-table” or “fusion” were part of the culinary lexicon, Van Aken was sitting on the back deck of Louie’s Backyard in Key West — a waterfront spot that would eventually become one of the island’s iconic restaurants — staring out at the Gulf. The restaurant wasn’t open yet. He had a stack of French and Moroccan cookbooks next to his coffee. Then he saw a boat sailing toward Cuba and thought, “Why am I cooking as if I’m somewhere else?”

“I realized I was oblivious to where I was living,” he recalls. “Why wasn’t I focusing on the ingredients and stories right around me?” he shares with New Times. Plus, “New Orleans had its own cuisine. California had one. The Southwest had one,” he says. “America was starting to celebrate its regional food movements. So why not Florida?”

That quiet realization became the seed of what he would later name New World Cuisine — a style rooted in the ingredients, cultures, and stories already alive in South Florida. He put away his European cookbooks and began exploring Key West with a notepad, documenting the preparation of Cuban, Bahamian, and Haitian dishes. The idea arrived quietly, but its impact would be enormous.

Norman Van Aken photo

Finding His Path — By Accident

Long before he became the chef who would define South Florida’s food identity, Van Aken was a young man in Illinois, drifting through odd jobs with no plans of becoming a cook. Then he spotted a classified ad that read, “Cook wanted. No experience necessary.”

“I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. But the heat, the rhythm, the camaraderie — it grabbed him immediately. That diner kitchen became his entry point into a world he hadn’t expected — but quickly knew was his.

He didn’t attend culinary school, though he would ultimately receive an honorary doctorate from Johnson & Wales University. Instead, he learned in real kitchens, absorbing technique from the cooks around him and shaping a philosophy centered on instinct, place, and story rather than rigid classical training.

Norman Van Aken photo

Key West: Where His Voice Emerged

By the early 1980s, Van Aken had moved to Key West, which was deeply influenced by Cuban, Bahamian, Haitian, and Southern cooking. At Louie’s Backyard, he began to understand the power of food rooted in place. “I realized I was oblivious to where I was living,” he says. “Why wasn’t I focusing on what was right around me?”

When he moved to Miami in 1991 to open A Mano at the Betsy Ross Hotel, he arrived with a sharpened vision. Inside the small kitchen, he hung a hand-drawn circular map of the Americas over the pass and told his cooks, “See that map? That’s where our food is coming from now.”

From Florida to Brazil, the Caribbean to the American South — the map defined the parameters of the cuisine he wanted to explore. It was the first attempt to give Florida a distinct culinary identity.

The national press quickly caught on. Time, the New York Times, Bon Appétit, and the London Times profiled him. His 1988 cookbook Feast of Sunlight helped bring national attention to his Florida-first cooking approach, and he went on to be the only Floridian chef inducted into the “Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America” by the James Beard Foundation.

Norman Van Aken photo

The Moment He Coined the Concept of “Fusion Cuisine”

If New World Cuisine was his thesis, “fusion” became its shorthand — a word that had existed for centuries, but one Van Aken was the first to apply publicly to cuisine.

In 1989, at a symposium in Santa Fe with chefs like Emeril Lagasse and Lydia Shire, he delivered a short talk titled “Fusion: The Synergy of Culture and Cuisine.” It was the first time the term had been used in a formal culinary setting, and it quickly entered the national vocabulary.

“I wanted to describe what happens when one culture meets another and they make something together that’s better than either alone,” he says. “It’s like laying down a salsa beat and layering another melody on top. When it clicks — that’s magic.”

The term stuck — and quickly became part of the way America talked about food in the 1990s.

Norman Van Aken photo

From the Keys to Coral Gables

After A Mano, Van Aken opened Norman’s in Coral Gables in 1995, where his cooking matured into a blend of street-food soul and fine-dining precision. Yuca-stuffed crispy shrimp with mojo and habanero tartar sauce and sofrito filet mignon — these dishes defined an era in which Miami’s dining scene became both local and world-class.

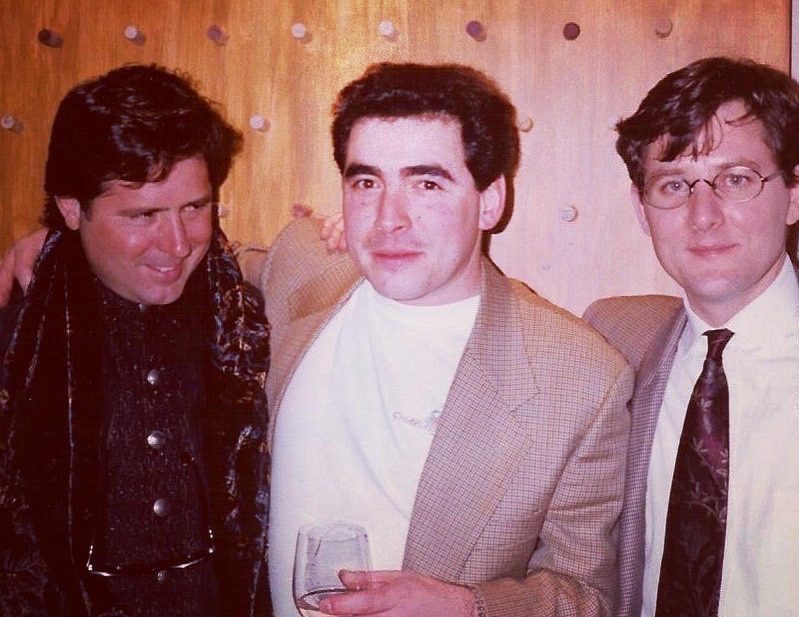

Over the years, Van Aken’s kitchens became incubators for a generation of Miami talent. Michelle Bernstein (Michy’s; Café La Trova), Michael Beltran (Ariete Hospitality Group), Miguel Massens (ex–Three; now developing his own project), and Phil Bryant (i.e., the Local; now culinary director for Michael White’s group) all passed through his doors.

“They all share that sense of being true to themselves and to their culture,” Van Aken says. “That’s what makes Miami so interesting — it’s not one voice, it’s many.”

Over the years, his dining rooms became magnets for high-profile guests. Paul McCartney visited (always vegetarian). Members of the Rolling Stones came through. So did Robert De Niro, Toni Morrison, and David Letterman.

“Some guests came two nights in a row for the exact same dish,” he says. “That’s the best compliment a chef can get.”

Photo by Nicole Lopez-Alvar

Miami Then and Now

Van Aken has watched Miami reinvent itself over and over — from the sleepy dining scene of the ’80s to the Art Deco revival of the ’90s to today’s high-gloss boom. Over the last five years, he has seen an influx of big-money restaurant groups from New York, bringing glitz and spectacle but often little connection to Miami’s culture or local ingredients. “It’s starting to feel like Vegas — a lot of flash, not enough heart,” he says. “The risk is that we lose Miami’s voice.”

He points to chefs like Michael Beltran (Ariete) and Michael Pirolo (Macchialina) as examples of the opposite: chefs who cook from where they stand and whose food reflects the land, seasons, and sensibilities of South Florida.

Even as he recognizes the challenges, Van Aken sees a brighter horizon coming into focus. He believes Miami may be on the brink of a shift — one that makes space again for smaller, neighborhood-driven restaurants and for chefs who want to express something personal rather than perform something glamorous. “Maybe we’re in a bit of a bubble,” he says. “But when it settles, I think we’ll see a renaissance — restaurants that really reflect who we are.”

He already sees that future taking shape in Little River, Little Havana, and Overtown, where chefs are building thoughtful, community-rooted restaurants — the kind of cooking that echoes the spirit of the movement he helped spark decades ago.

Screenshot via Instagram/@normansorlando

A Lasting Legacy That Sees No End

Over the decades, Van Aken’s influence has extended far beyond the restaurants he’s run. He’s written six cookbooks and a memoir, created a public-radio segment A Word on Food, and hosted the television series Norman’s Florida Kitchen, all of which helped bring South Florida’s ingredients and stories to a national audience. These projects — not an exhaustive list, but among his most defining — reflect the same curiosity and sense of place that shaped his cooking.

Now in his 70s, Van Aken splits his time between Norman’s Orlando and new creative projects. He’s working on a memoir about his nearly 30-year friendship with the late Charlie Trotter and developing plans for a teaching kitchen that would connect Key West, Miami, and Central Florida.

“I don’t want to retire,” he says. “I want to keep creating spaces where people feel human again, share a meal, and let the world go away for a couple of hours.”

If Miami is now a city with its own distinctive cuisine, Norman Van Aken helped draw its first map. His insistence that Florida’s flavors were worthy of celebration opened the door for everything that followed — from the mango-and-chile era of the ’90s to today’s blend of Caribbean, Latin, and coastal influences.

“People talk about New World Cuisine or fusion as if it were a trend,” he says. “But it’s not a phase. It’s who we are.”